An independent province Hakkari (1875-1888) was only of short life span, because already after 13 years the Ottoman border region was added to the province Van.

A triangle: Kurds, East Syriacs and the Ottoman State

In his travelogue Armenia: A Sketch of her nature and inhabitants (1878) the Austrian officer and author Amand Freiherr (Baron) von Schweiger-Lerchenfeld (1846-1910) described the complex relationship of East Syriacs (‘Nestorians’) and regional Kurds in the Hakkari sancak during the 19th century, emphasizing societal and cultural similarities between the two ‘mountain peoples’.

“To the south of the Van basin lie the former hiding place of the once famous Kurd prince Mahmud Khan. (…) Like no other in these infamous districts, he contributed to undermining prosperity, custom and order and to smothering the sparse culture for decades to come. In the course of his reign he had brought a hundred, mostly Armenian villages under his rule, and knew how to use his presumed sovereignty rights like hardly any of the ‘almighty Padishah in Rum’ [the Sultan in Constantinople], as the mountain peoples there say.

However, Mahmud’s power, too, was broken by the Turks, albeit without any good consequence for the inhabitants, who had now to do with the equally violent ‘liberator‘. Yes, the mountain tribes themselves have only morally lost through their contact with the official Ottomanism and their mostly naive character traits have been completely damaged if they came into more intense contact with the useless provincial bureaucracy. An administration that showed its illegal measures in a thousand little details could only insult the self-esteem of the mountain people, notwithstanding their own inadequate conception of the terms My and Yours, and where these could not escape the persecutions and oppressions of the authorities, they became hypocrites, perjurers, sophisticated thieves and highwaymen.

The worst conditions of all were in the Nestorian District of Hakkari (or Hakhiari), in the source region of the Great Zab. In the West, the mountain massif of the Djebel Djudi, which is situated between the named stream and the Tigris, and reaches east to the Persian border, borders this area. This is the local delimitation on Turkish territory. However, Nestorians also live in the northwestern Persia, especially around Urumiah, and scattered communities can be found even in northern Mesopotamia (near Feyshhabur and on the southern slope of the Chaspi Mountains), their former main seat from which they were soon expelled by the storms of the middle Ages. Only a few travelers have succeeded so far, to explore their current homeland, for which the reason lies as much in the inaccessibility of most of the remote areas of this alpine country, as in the savagery of its inhabitants, in which the Christian Nestorians and Mohammedian Kurds may have pretty much the same antidote. Furthermore, the only passage is the valley of the Zab, which divides the main mass of the alpine country. On both sides of the same are the dangerous hiding places of the Leihun Kurds, and it was this wild tribe that produced a Bedr-Khan, the most notorious slayer of Christians in the 1840s. When the whole area was in the grip of a fearful religious war, the Porte believed to intervene, but taken as a whole, it gave only the idle bystander and might have found silent pleasure in the fact that the wild mountain tribes, whether of this or that faith, destroyed each other. That the sympathy of the Ottoman government, namely that of the Turkish military commanders, was more on the side of the Kurds, is in the nature of things and so these found free hand to let their ancient hatred shoot the reins and clean up among the Nestorians. The relationship between the two mountain peoples as a whole has not always been an outspoken hostile one. Yes, every now and then, namely at the time of the abolition of feudalism under Sultan Mahmud II, with which reform action the power of the Dere-Beys (valley princes) should be broken, every antagonism among them disappeared, and they fought back with united strength the invasion efforts of the Porte. However, Bedr-Khan may not have remembered this erstwhile brotherhood.

The feuds are still frequent today, namely in the areas of Tiyari, where between snowy peaks in water rich valleys the stone huts of the Nestorians under enormous nut-trees lie. Further north, in the area of Julamerk, Nur-Allah had arranged the massacres. But he was later imprisoned, when he also resisted the intervening troops, and exiled to Kandia. That today the matters in this so remote corner of Turkish Asia are different, i.e. better for the Christians, no one will dare to presume, who knows the unbound ways of oriental mountain peoples.”

Source: Schweiger-Lerchenfeld, Amand: Armenien: Ein Bild seiner Natur und seiner Bewohner. Jena: Hermann Costenoble, 1878, pp. 100-103; http://www.deutschestextarchiv.de/book/view/schweiger_armenien_1878?p=134

Destruction

In his standard work Armenia: The Survival of a Nation (1980), the British historian, author and human rights defender Christopher J. Walker (1942-2017) summarized the fate of the East Syriacs in the sancak Hakkari during the First World War as follows:

“Besides the Armenians, another Ottoman people was deported and killed by its own government in 1915. These were the Assyrians, who confusingly call themselves Syrians. As Armenians were divided by the Russo-Turkish border, so Assyrians were divided by the Perso-Turkish border. In the Ottoman district that they inhabited they constituted a minority, but a substantial one, interspersed with Kurds. They were politically less sophisticated than Armenians, but the education that they had been receiving had taught them to demand greater autonomy, less subservience, and security from their predatory neighbors.

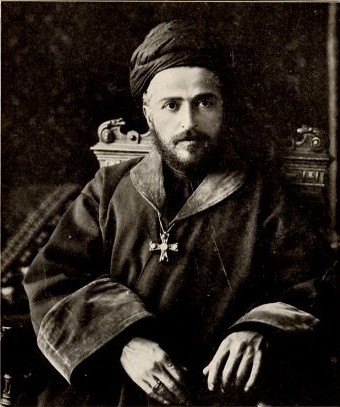

Persian Assyrians had been looted, sacked and killed by Turkish forces during their occupation of north-west Persia in the early months of 1915. This was only to be expected. But when the Turks were forced out of Persia by the Russians in May, the Turks turned on their own Assyrians. In mid-June (at the time as the assaults on Bitlis and Moush) an attack was launched on the mountain dwellings of the Assyrians, initially against Qodshanis (Kochannes) in the Hakkiari district, the seat of their spiritual leader, whose title is Mar Shimun. The mountains of Hakkiari, the homeland of this community, are more sheer and inaccessible than any of the mountains of Armenia. The attack was unprovoked. From within their church they defended themselves against Turkish regular soldiers for two days before their ammunition ran out, whereupon they escaped by night to Persia. At the same time, a second attack was launched against the Assyrian villagers of Tkhuma, Tiari and Baz. The villagers fought fiercely from their mountain strongholds for 40 days, before being compelled to take refuge near the top of a high mountain. The Turks tried to starve them out; but when the Russians had regained the initiative of the war, Mar Shimun[XIX (XXI) Benyamin] (a good shot himself) was able to go with a band of men into the interior to bring relief to the besieged men. Astonishingly, he reached them, and after many encounters was able to lead them back across the mountains to Persia. Fifteen thousand were saved. These episodes were only the beginning of the upheaval, dispersion and massacre that characterized the history of the Assyrians throughout the war and into the mid-1930s.”

Source: Walker, Christopher: Armenia: The Survival of a Nation. London: Croom Helm, 1980, pp. 206, 215