Toponym and History

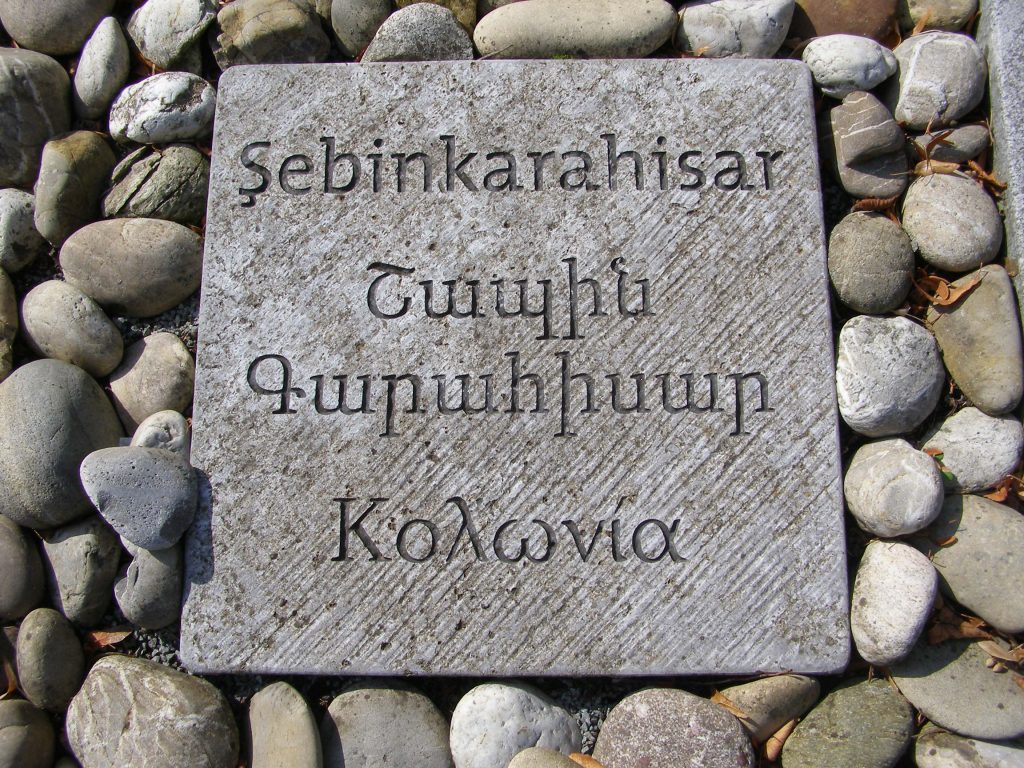

The recorded history of Şebinkarahisar begins with the Third Mithridatic War. After the defeat of Mithridates VI, the Roman general Gnaeus Pompey strengthened the town’s fortifications and founded a Roman colony (colonia). The 6th century Byzantine historian Procopius writes that Pompey captured the then ancient fortress and renamed it Colonia (Κολώνεια – Koloneia).

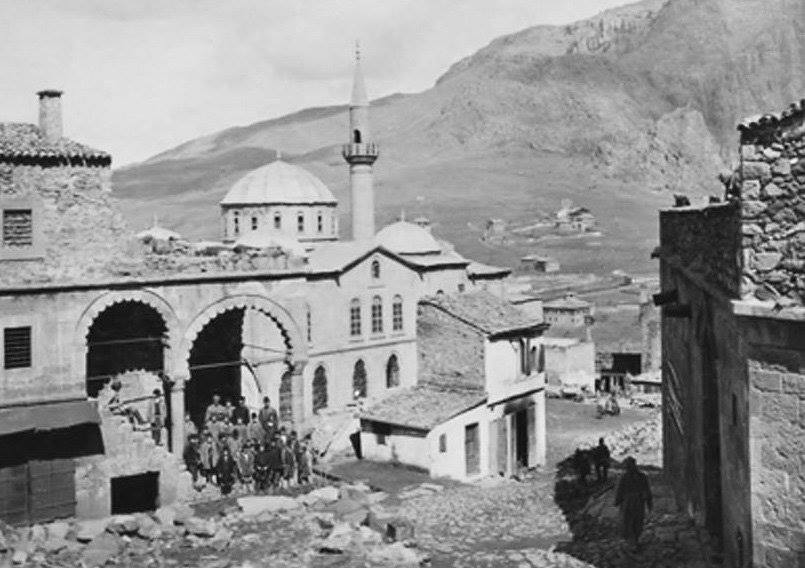

In the Byzantine period, the city was rebuilt by Justinian I (r. 527–565). In the 7th century, it became part of the Armeniac Theme, and later of Chaldia, before finally becoming the seat of a separate theme by 863. It was attacked by Arab raids in 778 and in 940.

Şebinkarahisar fell to the Seljuk Turks soon after the Battle of Man(t)zikert in 1071. It remained in Turkish hands since, with the exception of a short-lived Byzantine recovery ca. 1106. Through the following centuries, the fortress occupied a strategic position on the frontier between the Turkish-controlled interior and the Empire of Trebizond. The Danishmends held the fortress until the 1170s, when it passed into the hands of the Saltukids of Erzurum. In 1201/1202 the Mengujekids, vassals of the Seljuks of Rum, took over. Following the Mongol invasion of the mid-13th century, the fortress was under command of the Eretnids, who minted coins in the town. A succession of petty Turkmen warlords controlled the town until Uzun Hasan of the Ak Koyunlu took over in 1459, perhaps believing that the place constituted part of the dowry of his new Greek wife, the daughter of John IV of Trebizond. Mehmed II took the town for the Ottomans from Ak Koyunlu in 1461, and consolidated his rule over the area in 1473.

In the 11th century, a second name becomes associated with the fortress: the town retains the name Koloneia, but the fortress above is called Mavrokastron (Grk. ‘Black Fortress’). The Turkish equivalent Karahisar appeared first in the 14th century. The town was later called Şapkarahisar (‘Black Fortress of Alum‘) or Kara Hisar-ı Şarkî/Şarkî Kara Hisar (‘Black Fortress of the East’) to differentiate it from Afyonkarahisar farther to the west. The place has been known as Şebinkarahisar since the 19th century and both names were used.

Greeks and Armenians continued to call the administrative center Kolonia(s), but the same name was confusingly applied to Koyulhisar, too. Furthermore, the toponym Nikopoli(s) was applied to the cities of Şebinkarahisar and Afyonkarahisar, to Koyulhisar, and Suşehir.

The Third Pontos

“Pontos was divided into three regions: the Western section, which was named [H]Elenopontos in honour of Diocletian’s mother and included Amasya, Ibora, Euchaita, Andrapa, Zalicha, Sinope, and Amisos [today Amasya]; the eastern section, which was named Polemoniakos Pontos after its governor, Polemon, embraced Neokaisareia, Komana, Polemonion, Kerasus [Giresun], and Trapezounta [Trabzon]; and a third region called Kolonia included Nicopolis, its capital, as well as Sevasteia [Sivas], Satala, Sevastoupolis, and Armeniakos, which included both part [the province Armenia Secunda?] of Armenia Minor (Lesser Armenia). This geographical division was to last until the reign of Justinian.”[1]

Administration

In 1857, Şebinkarahisar was detached from the Trabzon province and together with Amasya, Tokat and Şebinkarahisar attached to the Sivas Province. According to different sources, the sancak Karahisar-ı Şarki was sub-divided into five to seven kazas, among them the four kazas of Şebinkarahisar, Alucra (also Me(h)sudiye/Ma(h)sudiye/Melet), Kizilhisar/Koyulhisar, and Suşehir.[2]

Christian Population

Of the four kazas of the sancak, most Greeks and Armenians lived in the kazas Şebinkarahisar and Me(h)sudiye/Ma(h)sudiye/Alucra. According to D. Ikonomidis, there lived 51,550 Greeks in the sancak of ‘Karahisar’.[3] The Greek Orthodox Metropolitan district of Kolonia consisted of 64 communities with 74 churches and 55 schools.[4]

In 1914, the sancak of Karahisar-ı Şarki/Şebinkarahisar had an Armenian population of 23,169, living in 44 towns and villages, placed under the jurisdiction of a diocesan council in the sancak’s capital Şebinkarahisar “that administered 38 parishes, two monasteries, and 36 schools with a total enrolment of 3,040. In this mountainous, wooded region, there was only one plain of any importance, the plain of Akşari/Sadağa, which lay south of Şebinkarahisar. The town of Enderes/Suşehir lay in the western part of this plain. Almost all of the sancak’s Armenian population was concentrated there.”[5]

Greek settlements in the Sancak Karahisar-ı Şarki / Şebinkarahisar

Cf. the list of Greek settlements in the sancak:

https://pontosworld.com/index.php/pontus/settlements/170-sembin-karahisar-nikopolis

Armenian settlements in the Sancak Karahisar-ı Şarki / Şebinkarahisar

Abana, Alamonik (Aramanyak), Akhshar (Ashkharhaberd), Aghvanis, Aghravis, Andreas (Enderes; Trk.: Endıres; since 1875 Suşehir; Armenian pop. 13,430), Aneghi (Anerghi, Anerği), Afsundu, Bedri, Buse(y)id, Burg (Burq/Burk’; Purg, Piurg), Gomeshtun, Demicilik, Dishkyoy (Dişköy), Dmluch, Tshaghakha, Eskişehir, T’amzara (Armenian pop. 1,518), T’andrjik, Ltarich, Khyutuk (Ghurtik), Tsiperi, Kamni (Hamam), Ktanots (K’rt’anots), Koyulhisar (Kolonia), Ghavaz, Ghrach, Maden, Mahmud, Mahsudiye (Mehsudiye; Alucra), Melet’, Melik Şerif, Mshkan, Mshkanots, Mushaz, Haghbasan, Nor Gyugh (Vari and Veri), Shapin Garahisar (Şebinkarahisar), Chamlija, Charbakh, Çiftlik, Chorakh, Corlu (Conlu), Palatiz, Tsrtak (Chrdakh), Sevindik, Sis (I), Sis (II), Uzkeni, Vari Atspter, Veri Atspter, Qecheli/K’echeli, K’echelurd/Qechelurd, Oreybil.[6]

Աբանա, Ալամոնիկ (Արամանյակ), Ախշար (Աշխարհաբերդ), Աղվանիս, Աղրավիս, Անդրեաս, Անեղի (Աներղի), Աֆսունդու, Բեդրի, Բուսեիդ, Բուրգ (Բուրք), Գոմեշտուն, Դեմիջիլիք, Դիշքյոյ, Դմլուճ, Ջաղափա, Էսքիշեհիր, Թամզարա, Թանդրջիկ, Լթառիճ, Խյուտուկ (Ղուրտիկ), Ծիպեռի, Կամնի (Համամ), Կթանոց (Քրթանոց), Կոյլուհիսար (Կոլոնիա), Ղավազ, Ղրաճ, Մադեն, Մահմուդ, Մասուդիե (Ալուջրա), Մելեթ, Մելիք Շերիֆ, Մշկանոց, Մուշազ, Յաղբասան, Նոր գյուղ (Վարի և Վերի), Շապին Գարահիսար, Չամլըջա, Չարբախ, Չիֆթլիկ, Չորախ, Չորլու (Չոնլու), Պալատիզ, Ջրտակ (Չրդախ), Սեվինդիկ, Սիս (I), Սիս (II), Ուզկենի, Վարի Ածպտեր, Վերի Ածպտեր, Քեչելի, Քեչեյուրդ, Օրեյբիլ:

Destruction

Greeks (1915-1922)

During and after World War I, the Greek Orthodox population of the sancak was subjected to massacres, deportations, forcible child transfer and forced Islamization. Between half (21,448 persons) to two thirds of the overall 51,660 Greeks perished in the Metropolitan District Kolonia, or the ‘district Kolonia’ respectively during this period.[7]

“Much information regarding the areas of Sevastia (Sivas), Nicopolis (Şebinkarahisar) and Kolonia (Koyulhisar) has been preserved by P. Kynigopoulos, a headmaster and active member of a committee for the dissemination of information relating to the genocide. According to his accounts, Islamized Greek women from the villages of Paltzana and Troupsi [kaza Şebinkarahisar] ended up in Turkish harems as early as 1916. In confirmation of this, Halil Topanoğlu, a Turk from Nicopolis, used to publicly boast that while he had been on the brink of starvation before the war, he was now enjoying a great life with his many Islamized (Greek) girls: it was almost as if he’d died and gone to heaven. In a letter from the afore-mentioned committee to the Patriarchate in Istanbul, dated 1917, complaints are lodged about several cases of forced Islamization in ten villages in the Kolonia [Karahisar-ı Şarki / Şebinkarahisar] district. According to these complaints, only 26 of the 200 Greek families from the village of Karacas had survived. The rest had been annihilated. One of the remaining families was that of the village priest, who were able to escape death due to the Islamization of the priest’s daughter and daughter-in-law. Of the 51,660 Greeks in the Kolonia district, only one third remained, and many of the survivors, mainly women and children, had been forced to convert to Islam.

According to Kynigopoulos, the Islamization of children was especially appalling. Worse of all was that the Turkish authorities seized Greek children from their families under the pretext of protection; the practice was also applied to toddlers and babies. The children were then sent to schools in Sivas to be educated as Turks.”[8]

“In 1918, the Ecumenical Patriarchate was given ‘Reports on the devastation and deaths in the diocese of Nicopolis [Afyonkarahisar] and Kolonia of Pontos’, in which the situation of the Greeks was described as follows: ‘The accessions to Islam can no longer be counted as the Turks exploit the poverty, hunger, cold and despair of the beleaguered Christians and violate ten-year-old girls for 100 drams of bread and convert the starving to Islam with a dish of lentils….and on the pretext of safeguarding the young, appointed government officials collected together all the young children, including babies, who are still being held in Turkish schools in Sevastia after Turkification… In the Tokati [Tokat; Evdokia] villages, the men were either killed or died of hunger. The women and children were forced to convert to Islam. The wealthy Greek Longinos, from the village of Karacevik, had all his properties seized and was forced to become an apostate. Moreover, he was obliged to abandon his wife and marry a Turkish woman, Ayşe’.”[9]

“G. Valavanis, an eye-witness, provides us with interesting data regarding the exceedingly high mortality rate in the Greek villages around Kolonia (Şebinkarahisar) and Nicopolis (Afyonkarahisar). In the village of Paltzana alone, 458 people from the village’s 280 families died on the way to Tokat. There, after having spent 18 months living in miserable conditions, they were ordered to return to their villages by the authorities. Before they reached their destination, however, they were to suffer more misery:

‘Topaloğlu Chalil [Halil], a monstrous fiend who was a goat-shepherd before the persecution began, and now has a harem of forcibly Islamized Greek women, came across the unfortunate Greeks, who were treading their dismal path, and attacked them ferociously, letting eight wild dogs loose on them. Unsurprisingly, they reached their deserted villages in the worst possible situation.

What they found there is beyond human imagination: houses, schools, and churches were all ruined. Not one stone was left in place.’”[10]

In his report to the Ecumenical Patriarch, which was also published in the Constantinople newspaper Nea Zoi (‘New Life’) on 12 November 1918 the Metropolitan of Neokesaria, Polykarpos, mentioned: “…having undergone indescribable torment—robbery, persecution, rape and massacre—the people of Kolonia were buried without mourning and deprived of the last rites in the inhospitable Turkish regions of Tokat and elsewhere.”[11]

“The gangs in the National Organization, gathering up the fanatical Muslim residents of every village, laid siege to the Greek villages and pillaged all over Pontos, warning that if the agreed terms of the peace [treaty] were not to their liking, the outcome would be catastrophic. Their threats, as M. Georvalidis records, concerning the people of Nicopolis, were put into practice on the villagers, who would have been totally obliterated if it had not been for the intervention of the Bishop of Sevastia (Sivas), Yervasios: ‘Kolonia has 96 villages in its nine regions of which the best and most fertile were emptied during the second year of the war after their inhabitants had been expelled into the hinterland; yet other villages, that had been affected by the goals of Young Turk ideology, have completely changed in appearance; what had been thriving Greek villages were now ruins, attracting only the sadness and infuriation of the observer. For those few who remained, life would have been intolerable if it hadn’t been for the timely appointment of the dynamic and indefatigable Yervasios of Sevasteia as temporary bishop for the area.’”[12]

The report of the Central Council of Pontos regarding acts of violence, which was dispatched to the Ecumenical Patriarch and the High Commissioner of Constantinople, N. Triantafyllakos, on 1 March 1922, reveals intentional cruelty and destructiveness: “In Supak, a village in the district of Kolonia [Şebinkarahisar], the Greeks Georgios Korpe Parasoglou, Georgios Korsoglis, Theodoros Termidis, Lazaros Mouratidis, Nikolaos Korse Parasoglis, Stavros Selever, Michail Tsintiler, Vassilios Tsintiler, Christos Eleftheriou, Kyriakos Tsilvanis, Vassilios Korsoglis, and Eleftherios Peskesoglous, had tar poured over them and were then set on fire.”[13]