Population

By 1911, of the nearly 120,000 inhabitants of the Samsun kaza (district), around 65% were Greek.[1]

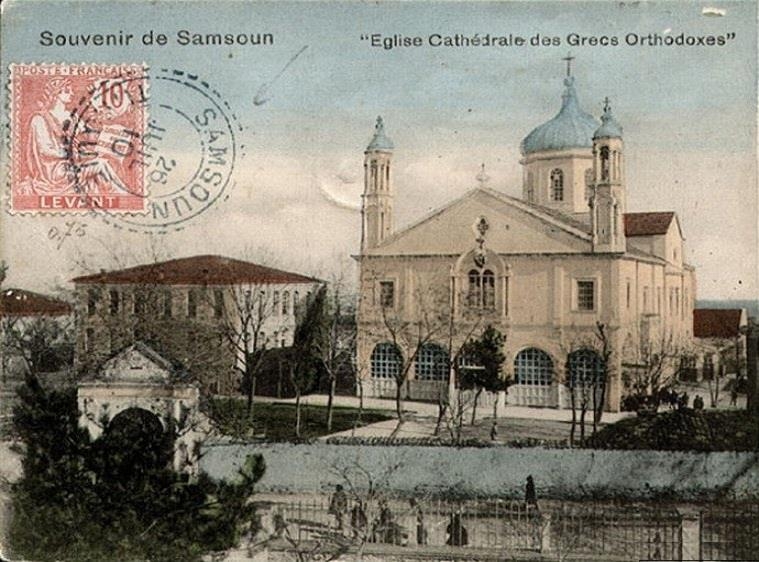

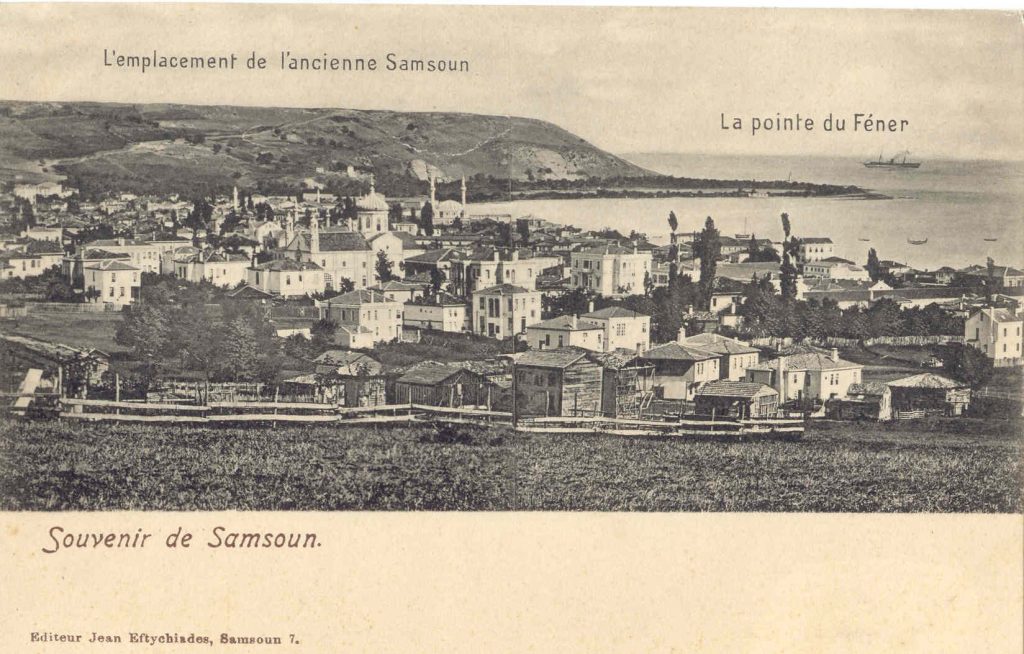

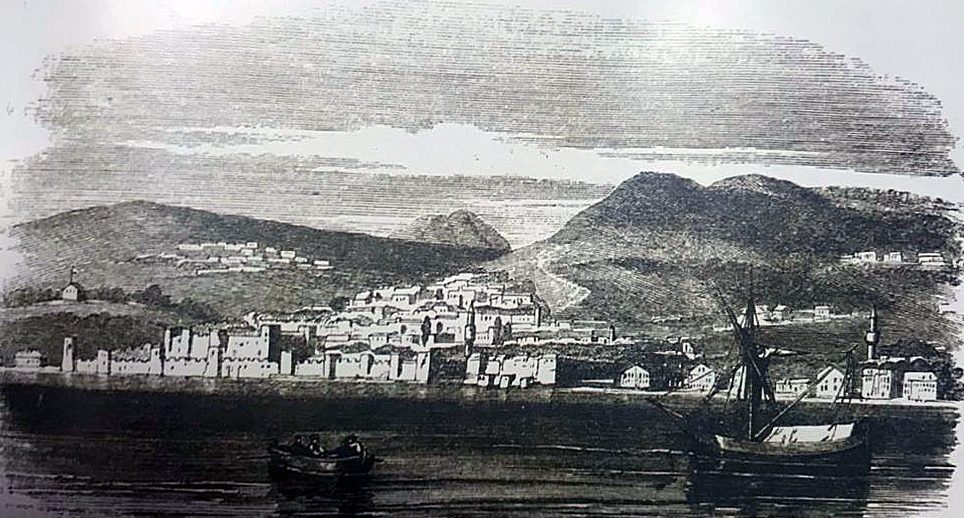

City of Samsun / Sampsounta – Σαμψούντα /Amisós – Αμισός

History

Byzantine and Seljuk Era

During the late antiquity and throughout the Byzantine era, Amisos was a significant town. Around 860 AD it was administratively a tourma in the thema Armeniakon. Amisos played a key role in Byzantine economy. In the second half of the 9th and throughout the 10th century it was a was an export center for cereals. During this period fiscal officials were stationed in the city.

Having been held by the Byzantines, Amisos seemed to have passed without a fight to the Seljuk Turks in ca. 1194, becoming part of the lands of Rukn al-Din, an ally of Byzantine Emperor Alexios III. In 1204, it passed equally casually to Alexios and David Komnenos (founders of the Empire of Trebizond), despite the recapture causing considerable disruption to the Seljuk Turks.

What seems to have happened at Amisos was Turkmen infiltration and settlement before 1194 and the establishment of a rival port of Samsun, side by side with Amisos (both located in the northwest quarter, east of the acropolis). Although Samsun was under Seljuk Turk rule during ca. 1194 to 1204, Amisos probably remained Greek and that there was a local accommodation of interests.

Classical Amisos, on the acropolis, was probably abandoned before 1194. Byzantine Amisos and Seljuk Samsun, were therefore probably situated on the coast (northwest quarter). The site taken by Seljuk Turks in 1214 presumably also represents Byzantine Amisos. The Genoese station of Simisso was established by 1285 (southeast quarter of Samsun) only an ‘arrows flight away’ from Samsun and provided protection to the local Greeks and Armenians, who formed seemingly still the majority of the population.

The town and castle of Samsun was probably established as a Seljuk Turk settlement after the Seljuk ‘recapture’ in 1214. In 1242, the Mongols defeated the Seljuks and forced them to tributary status. As a consequence, the Empire of Trebizond who were Seljuk vassals for the past decade, consequently changed masters. But after the Mongol withdrawal, Samsun was ceded to the Turkmen Isfendiyaroğlu dynasty of Sinope.

Ottoman Period

By the 14th century, Turkish Samsun and Genoese Simisso were still distinct settlements existing side by side. The Genoese colony Simisso (on the southeast quarter) was relatively important. The two places (Genoese Simisso and Turkish Samsun) were an effective partnership of Italian capital and naval expertise with Turkish merchandise and supply routes. Millet, barley, beans and chickpeas were exported from Simisso to the territories north of the Black Sea. From there, Simisso received hides, edible fats and slaves.

The Ottoman sultan Bayezid I captured Samsun around 1393 but the Mongols blocked all trade through it in 1401. By 1404 Samsun was in the hands of Bayezid’s son. The Turkmen Isfendiyaroğullari from Sinope retook Samsun in 1419, but it returned to the Ottoman sultan Mehmet I shortly afterwards. Except for the period 1233–48, Ottoman Samsun does not seem to have been notably important although it offered the Ottomans access to the Black Sea.

During Timur’s (Tamerlane) incursion and after the Ottoman reoccupation of 1419, trading conditions became less profitable. The Genoese colony left shortly after 1424 having set fire to their base. After 1452 the, now presumably single, town fell into a decline until its astonishing resurgence in the 19th century.

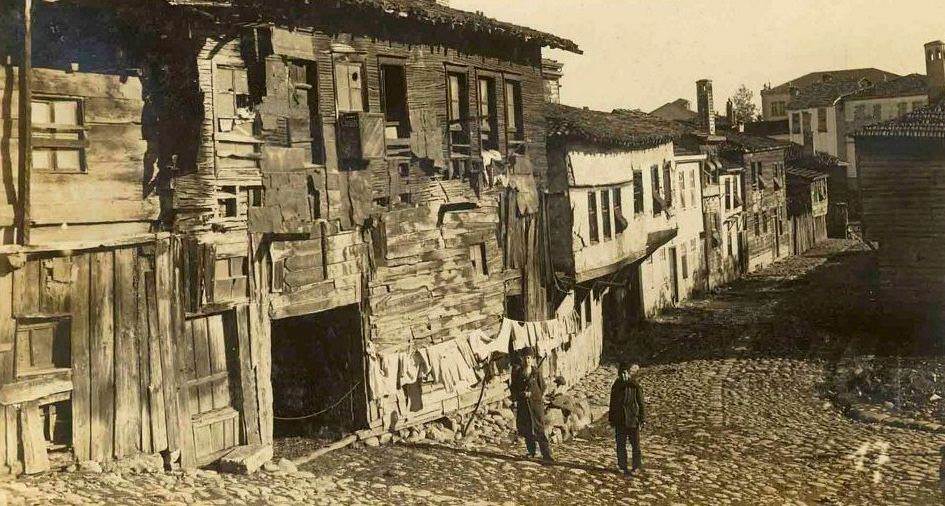

In 1701, French botanist Joseph Pitton de Tournefort found a village built on the ruins of ancient Amisos. In 1813, the Scottish officer John Macdonald Kinneir observed that the ships from the port were navigated by Greeks; for although the population of the town was almost entirely Turkish, the adjoining villages were primarily populated by Christians.

In 1806, Samsun burnt to the ground, and by 1829 it was still recovering.

From the 15th century, Samsun had been a depressed village. Its revival began with the building of the metalled highway south to Amasya and with the expansion of the tobacco industry of nearby Bafra. By the 1860s, Samsun became the port of the main Constantinople-Bagdad route and was finding international markets for its tobacco.

Excerpted from: Sam Topalidis: A History of Amisos (Samsun), 2013. http://www.karalahana.com/2015/10/23/a-history-of-amisos-samsun/

Population

In October 1838, Henry Suter visited Samsun and thought the town had a population of 450 Turkish and 150 Greek families. In 1847, Ferrukhãn Bey also visited Samsun and recorded it comprised 500 Turkish, 240 Greek, 60 Armenian and a few European households. In 1864 the American artist John Henry van Lennep observed the city of Samsun faced the northeast built in the shape of a crescent with a promontory sheltering it on the northwest. He also observed that Foreign Governments found it difficult to induce any of their officers to reside in Samsun as it was an unhealthy place due to the diseases that could be caught there.

The most impressive feature of the revival of Samsun (as well as Bafra) since 1860 was that, with small local resources, the Greek proportion of the population rose to 40%. This massive rise in the Greek population was due to immigration, especially from the west coast of Turkey and Constantinople.

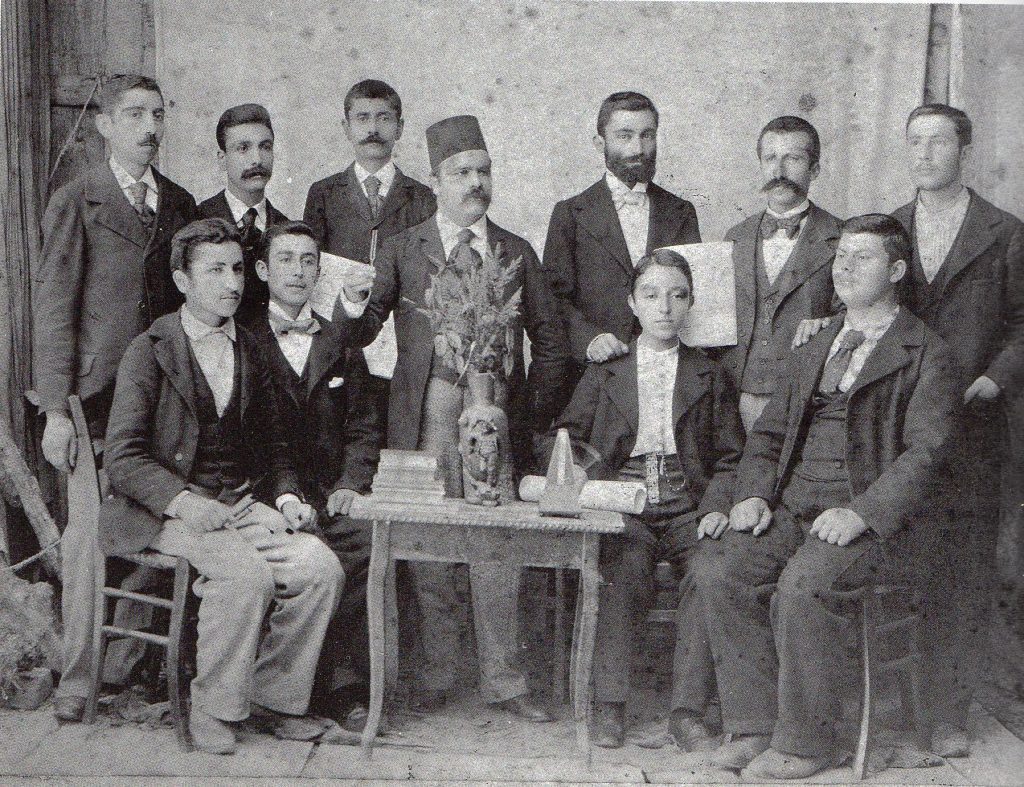

The city of Samsun, unlike its surrounding villages, was not occupied mostly by Greeks, but Greeks dominated its commercial life. Of the 214 businesses in Samsun in 1896, no fewer than 73% were owned by Greeks and 17% by Armenians. In 1910, Samsun numbered around 40,000 souls, and Greeks, Armenians, or Franks controlled no fewer than 91% of its 156 businesses and 85% of the shares of the Bafran tobacco market. Its rapidly rising population is believed to have overtaken that of Trabzon about 1910.

Approximate indication of the populations of Trabzon and Samsun, 1860 to 1925 (1,000)

| Year | 1860 | 1870 | 1880 | 1890 | 1900 | 1910 | 1920 | 1925 |

| Trabzon | 34 | 35 | 36 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 33 | 24 |

| Samsun | 4 | 7 | 9 | 11 | 17 | 40 | 33 | 20 |

William John Childs who travelled to Samsun at its peak in 1913 stated the town stretched along a beach for a couple of miles, and its suburbs went up the slopes of foot-hills behind in a scatter of white buildings. There was no esplanade or marina facing the sea; offices, warehouses, and cafes push their backs down the shore as far as possible. He stated the town was commercial in its interests and had no wish to think of amenities. It is a growing town of some 40,000 people despite Turkish neglect. Much of the trade and wealth of the town was still in the hands of the Ottoman Greeks.[2]

Excerpted from: Sam Topalidis: A History of Amisos (Samsun), 2013. http://www.karalahana.com/2015/a-history-of-amisos-samsun/

According to the census of the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople, 5,315 Armenians lived in the city of Samsun at the beginning of the First World War, where they maintained a church and three schools with 610 students.[3] “In October 1915, there remained, in Samsun, only eleven Islamicized families, two Armenian families whose members were Persian subjects, the families of two doctors working on the front, Dr. Kasabian and Dr. Ajemian, and about 100 children from three to six years of age who were first taken in by Greek families, then taken from them by the authorities and handed over to Turkish families.”[4]

Black Sea Ports and Long-Distance Trade: Observations of a Prussian Military Officer in 1838

On 8 March 1838 Helmuth von Moltke (1800-1891), at that time instructor of the Ottoman troops, wrote to his mother from Tokat:

“(…) The sight of Samsun is most pleasant; an old Genoese fort, several well-built Turkish konaks, some stone mosques and khans [caravanserays] stand out even from a distance. The whole town is surrounded by an olive grove, which covers the mountainous amphitheater and from which friendly kiosks and garden houses look out; the tops of the hills are crowned by a Greek village, and behind it are wooded crests which may have their 3000 feet high. I used the evening to take a map of this place, the harbour and the surrounding area, and it seemed strange enough to set up my English patent measuring table in Pontus, in the land of the Mithridate.

It has happened that I have now got to know almost all the ports of the Black Sea from the mouth of the Danube to the Kizil-Irmak [Kızılırmak; ancient Grk: Ἅλυς – Halys’]; they are all bad. The Black Sea, so disreputable from time immemorial, is neither stormier nor as often covered with fog as our Baltic Sea, and shallows and cliffs like that do not exist at all; the great danger lies mainly in the lack of protected anchorages and ports. (…) The northern coast of Asia Minor offers only two points (Eregli and Sinope) near Samsun, i.e. within a hundred German miles, where ships can seek shelter. In bad weather, the ship cannot land at Samsun at all, but takes its passengers with it as far as Trebizond, because the very low spits of land, which are four miles out, which the Kizil and Yeshil [Yeşil]-Irmak (the red and the green rivers) have washed up, make access in dark weather too dangerous. But the port of Trebizond is no better, and even though a very important trade is done over this place, not the slightest thing has been done to make it look like a seaport. Not even a quay or landing place is there; the bales are carried by people through the water into the barges.

The East Indian trade used to take its way through the Levant. The Genoese were masters of all the ports on the coast of Asia Minor as well as in so many other points of the Ottoman Empire. Everywhere they have left permanent traces of their rule; their installations are characterized by solidity and efficiency; their old castles still stand and, by their profile, mock the later Turkish installations, but the piers, which at that time protected their ships of smaller size against the waves, are today swallowed up by the sea. The total disruption and lack of security that came with the Turkish domination led that important trade to a new canal and made it take the just recently discovered sea route. Today, the East Indian trade seeks the old route. The Euphrates expedition was a first attempt in this direction, and the connection through the Red Sea by steamships is really established.

Persian merchants used to visit the Leipzig Fair, from where they fetched factory goods and fur. The journey usually lasted fifteen months and was subject to countless dangers and complaints. Today the same merchant travels from Trebizond by steamship in 34 days via Constantinople and Vienna to Leipzig and returns in 20 days. I believe that these very steamships will be one of the most important means of civilization in the Orient, and that Austria has more merit than any other country for its great enterprise. (…) From the small Asian ports the steamship brings tobacco, fruits, raw silk, Persian scarves, gall apples (which are a great article of trade) and Persian gold and silver coins, which are minted in Constantinople for bad money.”

Translated and quoted from: Moltke, Helmuth von: Unter dem Halbmond: Erlebnisse in der alten Türkei 1835-1839. Berlin: Verlag Neues Leben, 1988, pp. 208-210

Excerpts from the Report of the Armenian Survivor Payladzo Captanian (Samsun)

Payladzo Captanian (Փայլածո Կապտանյան, 1882-1968) came from Samsun, from where she, as a pregnant woman, was deported with her husband via Tokat, Sivas and Malatya/Fırıncilar to Dayr-az-Zor (Syria) in July 1915. The more than 300 men of her convoy were already separated from their families and murdered in the village of Tonuz. In Aleppo, Captanian gave birth to her third child and successively worked as a maid, nurse, teacher, worker in Ottoman army workshops and milk supplier. In Constantinople in 1918 she was reunited with her two sons, whom she had left with a Greek family in Samsun, and emigrated with her children to New York, where she worked as a seamstress and sewed draperies for President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s home in Hyde Park, New York. After World War II, Pailadzo and her family moved to San Francisco. While in San Francisco, she rented a room to Lois and Tom DeDomenico. Pailadzo taught Lois how to make Armenian pilaf and in 1955 Tom and his brother Vincent, who worked at the Golden Grain Macaroni pasta company founded by their father, came up with the initial recipe for the rice-and-macaroni mixture called Rice-A-Roni.

Payladzo Captanian wrote down her memories of the deportation period as early as 1919, i.e. very close to the events, in the hope that the French edition of the memoirs would have some influence on the Paris Peace Conference; it was published under the title “Mémoires d’une déportée”. Her book contributed to Raphael Lemkin’s re-search and his understanding of the Genocide. Below you will find some excerpts from the first German edition (1993) of her memoirs:

“The deportation began. (…)

Finally, we learned that we were to be escorted to Dayr-az-Zor. We looked at a map and knew that the journey would be long and arduous under the summer sun. We also sensed that we would be walking and foresaw that death would await us on the long journey. Faced with this prospect, there was discord in several families. In the face of this perspective, some men converted to Islam, while women and children held on to their faith and preferred exile. One woman preferred to poison herself and all her children rather than follow her husband’s example. (p. 20)

(…)

A little later we witnessed a terrible spectacle. We saw how pitiful old women, who had to walk all the way, began to throw themselves into the river one by one. Martyred by hunger and thirst and completely exhausted, they had decided to end their lives. Turks sitting on the riverbank watched this scene unmoved. I asked the gendarmes if they would save the women. One of them replied cynically that this river already carries a lot of human bodies. ‘There will come a time,’ he added, ‘when you will look for a river to drown, but then you won’t find one. Isn’t it wise to take the opportunity now to free yourselves as soon as possible?’ (p. 48)

(…)

‘Unhappy are the women who are pregnant and nursing these days!’ This Gospel passage was especially true for the poor deportees. How many women were killed in the streets and how many lost their children! They were completely abandoned. The gendarmes beat them mercilessly. They were not allowed to stop running and often died together with the newborn child. One woman was still writhing under the pain of childbirth when a gendarme stole her clothes. He hadn’t left her anything to wrap her child, who was shivering with cold. Another deportee rushed over and covered the baby with a piece of clothing. Five minutes later the order to leave came. The woman who just had delivered birth had to hurry so as not to be left behind. She ran and left a trail of blood behind her. (p. 79)

Translated and excerpted from: Captanian, Pailadzo: 1915: Der Völkermord an den Armeniern; eine Zeugin berichtet. Übersetzt, bearbeitet und mit einem Nachwort versehen von Meliné Pehlivanian. (Leipzig: Gustav Kiepenheuer Verlag GmbH, 1993)

Sam Topalidis: Arrival of Mustafa Kemal and the Destruction of the Remaining Christian Population

The Armistice between the defeated Ottoman Empire and the Allies in World War I was signed on 30 October 1918 at Mudros harbor on the Greek Island of Lemnos. Allied soldiers were then stationed in Turkey to enforce disarmament and maintain order. No sooner had the Greek guerrillas and the survivors of the deportations returned to their villages after the end of World War I, that they were once again confronted with difficult choices. Once again Pontic Greeks were compelled to flee to the mountains, go into exile or face certain death.

Around Giresun and Samsun there was noticeable intercommunal tension, where there was a sizeable Greek population. As a consequence, in March 1919, 200 British soldiers arrived in Samsun to help establish order.

In early May 1919, Mustafa Kemal (the future Atatürk) became inspector general of the Ottoman Ninth Army, encompassing much of eastern and northcentral Turkey from Samsun. He was tasked with restoring order, to gather the arms and ammunition laid down by the Ottoman forces and prevent resistance against the government. He had command over the army and all the civil servants in the area. It seems clear that he was expected by the War Ministry and possibly the sultan and grand vizier to organize resistance.

On 19 May 1919, Mustafa Kemal arrived in Samsun. This date is marked as the beginning of the Turkish War of Independence and heralded the establishment of the Turkish Republic in 1923. Samsun’s trade was again in the hands of the Greeks whose traders had grown rich as dealers in tobacco and hazelnuts. In the same month, Kemal sent a confidential letter to corps commanders under his authority to raise a popular Muslim guerrilla force until a regular army could be organised for defense.

A primary instrument of the genocide of Pontic Greeks was Topal Osman[5] and his cut-throats who, with the connivance of the Ankara Government wreaked destruction on the unarmed Greeks from Tripolis and Giresun to Samsun. The New York Times summarized the events in 1921:

“… The notorious murderous chief, Osman Agha [Topal Osman] arrived at Samsun the second day of Bairam [Muslim festival] … Then surrounding the stores of the American Tobacco Company, he arrested all Greek clerks, numbering about 800, and had them transported to an unknown destination. The Greek quarter was then surrounded and 1,500 other Greeks arrested and transported to the interior. The population of thirty other villages of the Samsun region was massacred while they were being transported to the place of exile. … Other villages, having refused to comply with the deportation order, were set on fire by the Turks, and the inhabitants, regardless of age and sex, were killed.[6]

On 3 June 1921, Samsun was surrounded and 1,400 men, aged 17 to 70 years old and 280 young men were imprisoned. The young men were drafted into the army. Then, the scenes of exhausting deportations to the interior, as well as massacres, began.

First convoy: 1,040 men started out on 4 June 1921. At Kavak (50 km southeast of Samsun), 701 were killed. The rest marched until Malatya.

Second convoy: 677 men started out on 5 June 1921 for Kangal and Malatya.

Third convoy: 1,085 men started out on 7 June 1921. At Tsompus Han, 30 km from Samsun, they were caught in a massive crossfire and 700 men were killed. Half an hour further at Mahmur Dağ, an additional 120 men were shot dead. The 265 men, who were lucky to survive, continued on to Malatya.

Fourth convoy: On 12 June 1921, 580 men set out for Havza. From there 351 old men were sent inland to Amasya. The other 229 young men were sent inland to Çorum (pronounced Chorum) where 397 more young men from different provinces were added. At Seitan Deresi (Devil’s Valley), 4 hours from Sungurlu, all 626 men were butchered.

Fifth convoy: 365 men set out in June 1921. At Tokat, they were united with 101 men from Ünye [Grk: Oinoy]. In Sivas more men were added from other cities creating a total of 1,066 men. They walked and whoever survived arrived at Kangal. The men from Samsun and Ünye were sent to Elbistan. The rest went to Malatya.

Sixth convoy: 262 men, 50–60 years old set out in August 1921 and most arrived at their destinations of Malatya, Harput or Diyarbakir.

Seventh and eighth convoys: 39 men and 450 women and children. Few arrived at Malatya in September 1921 having died from hunger and disease.

Ninth convoy: 206 men were sent out in September 1921 for Bitlis. On the road 166 died, most of them from freezing temperatures in the Deli Taş Mountain.[7]

After the deportation of the Samsun Greeks, atrocities and deportations continued in the 394 Greek villages of the adjacent districts during the following three months.

In the Samsun area in the final quarter of the 1922, as the Turkish army prevailed in Anatolia, there was a fresh drive to rid the Black Sea region of its remaining Orthodox Christians. The Christians could see that escape by sea was their only hope, yet their exodus from Black Sea ports was snarled by the mutual suspicion between Turkey and Greece. Because military age males were forbidden to leave Turkey, the surviving Greek males of military age not conscripted into the labor battalions had to leave by covert methods.

By December 1922, Greek Samsun was vanishing like Greek Smyrna had done three months previously. At the same time, the unarmed members of their community – tens of thousands of women, children and old people were staggering down the mountains towards the port, in the hope of being shipped to Greece or any other place of safety.

Information dated 27 November places the numbers already arrived at Samsun from the interior at 30,000. On 7 December, 7 ships had recently arrived at Constantinople from Samsun crowded with such refugees as were able to pay seven Turkish pounds as passage money. In the end it was Turkish ships who took many of the refugees away from Samsun, in hellish conditions, in part because many people were sick before they boarded.

In 1925, after the deaths and deportations of the Ottoman Christians from Anatolia, Samsun’s population fell from 40,000 in 1910 to 20,000.

During the exchange of populations, over 22,000 Muslims from Greece were brought to Samsun to replace the departed Ottoman Christian Greeks. Samsun’s population had thus recovered substantially by 1927.

Source: Topalidis, Sam: A History of Amisos (Samsun), 2013. http://www.karalahana.com/2015/10/23/a-history-of-amisos-samsun/

Konstantinos Emm. Fotiadis: The nine Deportation Convoys of Greeks from Samsun, June-September 1921

Nine large forced marches were needed to evacuate the Greek population of Samsun. This action took place within a matter of days. The crime of genocide had to be completed quickly, before any international humanistic organizations or allied countries could protest. An account of the first forced march has been given by Georgios Valavanis: “The escorting gendarmes, who were mostly felons, criminals on the run, and professional killers (such people made up 90% of the Turkish gendarmerie), led the grim convoy to the arranged place, where armed Turks from the surrounding villages were waiting. The convoy was kept there until nightfall; then, gunshots were fired from the surrounding area as a signal to attack the unsuspecting people of Samsun”.

The second forced march took place on June 5/18, 1921, and consisted of 677 men. This forced march arrived at their destination safely. The third forced march, which set out on June 7/20, numbered 1,085 of the most outstanding youths of Samsun. When they reached Cubus Han, the irregulars of Osman Feridunzade appeared, led by his chief soldier, Osman Nuri. They attacked them from all sides, fully armed. The escorting gendarmes also participated in the general massacre. Only 5 or 6 people survived to denounce the atrocious slaughter. All the dead were robbed. The Sarafoğlu brothers, who survived, were forced by the mayor of Samsun, Kansiz Osman, to hand a cheque for 3,000 lire over to Osman Nuri and to sign a document intended to mislead European countries which stated that the attack was the work of Greek partisans.

The fourth forced march started on June 25, 1921. In order to save their families, 580 young men were forced to surrender to the military authorities. When the latter arrived in Havza, they singled out 229 young men, to whom they added 397 more from other areas, and took them to Çorum via Merzifon. On July 3, 1921, they were ordered to march to Sungurlu, their final destination: “But when, after a four-hour march, they reached the infamous Creek of the Devil (Şeytan Deresi), the executioners of Osman Ağa and Tiassar Çavuş bound them in groups of four and butchered them. According to Kurdish witnesses, the dead bodies were robbed and left unburied to be eaten by dogs and vultures.”

The fifth forced march was comprised of 365 youths from Samsun, 101 from Kotyora [Ordu], and 600 from Kerasus [Giresun]. This group of 1,066 set out for Malatya. They encountered their first mishap at the Cubus Han, a few kilometres outside the city of Amasya. This location had already served as a Golgotha for the Greeks on several previous occasions. The forced marchers were robbed by ςeteler and Turkish villagers, and the youths were taken to Amasya naked. For two months before reaching their initial destination of Malatya, they were taken from Turkish village to Turkish village, still naked and now starving. Few survived the ordeal.

Four other forced marches from Samsun followed. The last one was on September 13/30, 1921. Within 100 days, Mustafa Kemal had achieved what the authoritarian sultans had not been able to accomplish in centuries: a total of six thousand men had been displaced in nine forced marches. Only a few survived and managed to return home.

When the deportation of the Samsun Greeks was complete, attention was turned to the 394 Greek villages in the surrounding area. The presence of Osman Feridunzade and his irregulars was decisive. He left nothing standing, slaughtering, dishonouring, and burning many alive. He threw many Greeks into their own burning houses. Every day he would make group arrests and commit robbery, rape and murder. He would confine the arrested in schools and churches, which he then set fire to. The burning of the village of Ata is characteristic of the situation that prevailed in the province.

Excerpted from: Fotiadis, Konstantinos Emm.: The Genocide of the Pontian Greeks. Monee, Ill., 2019, p. 394-396