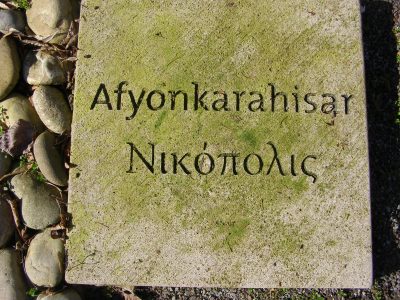

The Toponym

The place was known to the Hittites as Hapanuwa. After the death of Alexander the Great the city was known as Akroinos or Akroinon (Ακροϊνόν), or Nikopolis (Νικόπολις – ‘City of Victory’; latinized: Nicopolis) in Ancient Greek. Its name under Seljuk rule was Karahisar-ı Sahib, the ‘Black Castle of Sahib’. This goes back to the Seljuk vizier Sâhib (Sahip) Ata, who had the castle repaired. The area thrived during the Ottoman Empire, as the center of opium production. Since 1928, the Turkish word afyon (‘opium’) was officially prefixed to the toponym as a reflection of the region’s main product, which made Afyon a wealthy city long before the foundation of the Turkish Republic.

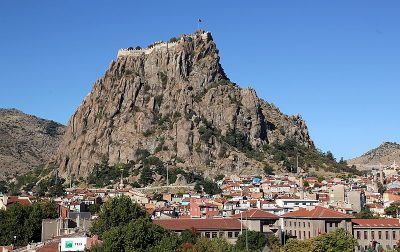

History

Hardly anything is known from its ancient history. The top of the volcanic rock (201 meters) in Afyonkarahisar, where Hittite traces of settlement can be found, has been fortified since Hittite times, and was subsequently occupied by Phrygians, Lydians and Achaemenid Persians until it was conquered by Alexander the Great. Akroinon/Nikopolis was ruled by the Seleucids and the kings of Pergamon, then Rome and Byzantium. The Byzantine emperor Leo III after his victory over Arab besiegers in the Battle of Acroinon in 740 renamed the city Nicopolis. It was taken from the Byzantines by the Seljuk dynasty of Iconium (Konia; Konya) in the early thirteenth century. Following the dispersal of the Seljuks the town was occupied by the Sâhib Ata and then the Germiyanids. It came under Ottoman rule briefly in 1382 (or 1392)–1402 and then conclusively in 1428–29. Kara Hisar was the capital of an Ottoman sancak. Being of military importance due to its proximity to the independent principality of Karaman, it is mentioned in connection with various uprisings: the Celali uprisings in 1602, the revolt of Baba Ömer in 1631 and the revolt of Abaza Hasan Pasha in 1658. In 1833 the city was temporarily occupied by Ibrahim Pasha, the son of Muhammad Ali Pasha. In 1902, a fire burning for 32 hours destroyed parts of the city.

During the 1st World War British prisoners of war who had been captured at Gallipoli were housed here in an empty church of the deported Armenians at the foot of the rock. Karahisar was heavily damaged in the Turkish War of Independence (1919–22), when it was occupied twice by Hellenic forces. However, in the decisive Battle of Kocatepe Hill, from 26 to 30 August 1922, the Nationalist Army under Mustafa Kemal succeeded in striking a decisive blow against the Greek troops. This made the quick advance to the coast and the final victory possible.

Population

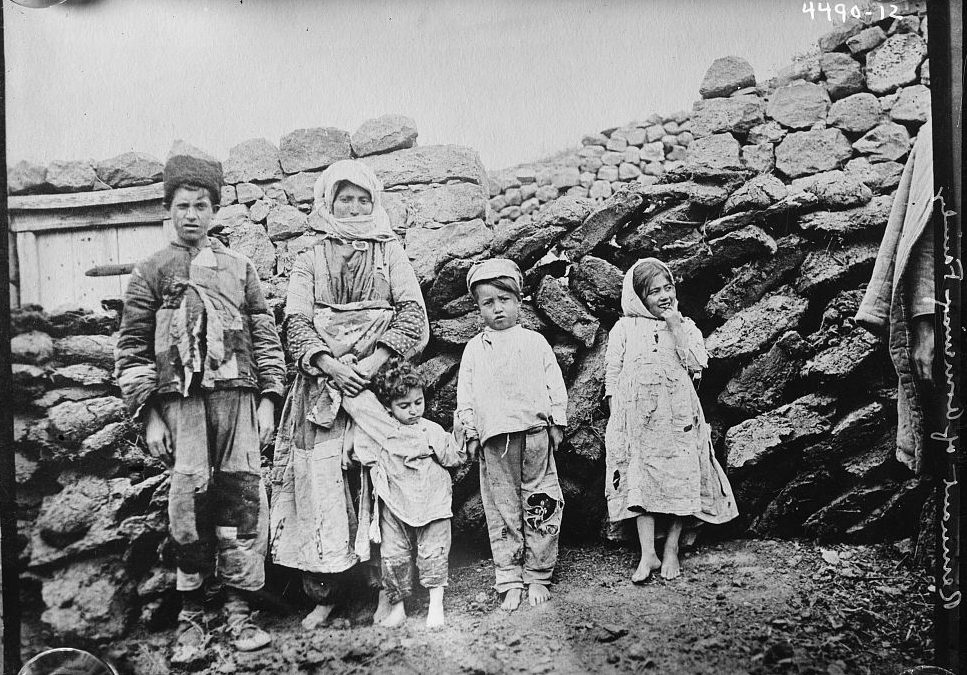

In 1914, there lived 7,448 Armenians in the sancak of Karahisar, most of them in the district center (6,500). All Armenians in this district were Turkophone. The Armenian community of Karahisar was reputed for its production of furniture and objects made of wood inlaid with silver. There were also small communities in the kaza of Aziziye, to the north of Afyonkarahisar, in Muzlice and Sandiklı (pop. 170). [1]

Armenian population

“Armenians in Afion-Karahisar are first mentioned in sixteenth century Ottoman fiscal registers. (…) The community, which was made up largely of Armenian Apostolics but later coming to include Evangelicals and Catholics as well, was situated in the center of the town. The city and its population grew steadily over the following centuries. (…)

Afion-Karahisar had a population of 45,000 in 1914, 7,000 of whom were Turkish-speaking Armenians engaged primarily in handicrafts and commerce but with some serving as locksmiths, glassmakers, lawyers (representing foreign firms), chemists, and physicians. The community had two Armenian Apostolic churches, Surb Astvatsatsin and Surb Toros, one Armenian Evangelical church, six schools and a kindergarten, and a number of cultural institutions, including two libraries. Many Armenians were subjected to the persecutions of the Abdul Hamid era, and many more perished during the genocide when they were deported in August 1915. Though the Church of Surb Astvatsatsin was vandalized during the genocide, a part of the structure still exists.”[2]

Deportation

The Armenian population of the villages in the Aziziye kaza was deported on 13 August 1915, with the exception of 27 artisans and their families, who had to convert. Two days later, the Armenians of the district center were deported.

On his way into exile, the Armenian Apostolic Patriarch Zaven discovered on 2 October 1915 six labor soldiers, first in Kayim, then in Nehiye, who were the reminder of a labor battalion of 150 Armenians and 100 Greeks, most of them originating from Afyonkarahisar and Kütahya; they were constructing a road to Ana.(3)

Like other cities in Bursa province, Afyonkarahisar became a transit camp for Armenian deportees during the First World War. The director of the Baghdad Railway to Constantinople reported his observations to the German Embassy in October 1915: “There was a camp across from the train station in Afion Karahissar that, according to credible statements, held approx. 12,000 Armenians when my train passed by, and at times was populated by 50 to 60 thousand people. Accommodation was of the most primitive sort, in tents that the people made from their bedding or any other material; a very large number lay completely without shelter of any sort.”(4)

Sargis Yetarian (b. 1907, Afyonkarahisar): Survivor’s Testimony

“In 1915, most of the Armenians living in Afyonkarahisar, Uşak, Eskişehir, Akşehir, Bursa, Bilecik, Kütahya, Adana, Maraş, and Ayntap were Turkish-speakers. All of them were deported. What they were guilty of, they did not know.

I remember the Armenians went to church, knelt, bowed to the ground and prayed in the form of namaz[5]. After mass, the sermon was delivered in Turkish. The priest told the people to obey the government, assist the Ottoman Empire to persevere, and not to spare any effort and muscle to fulfill their duty towards the country. We, the Armenian women, were considered Ottomans, our Armenian women wore chadras, like Turkish women, the only difference being that the Armenians’ were white mahrama, and the Turkish was black chadra, in order to tell one from the other.

When I was born my mother had fallen ill and she had not been able to breastfeed me. In those days, there was no alternative food for babies. Our people did not pay any attention to me: they tried to cure my mother. My great aunt had taken me to a Turkish woman and asked her to feed me together with her son.

The mass deportation started at the beginning of 1915. Then, certain people were given some privileges. For instance, the families of the soldiers serving in the Turkish army, the families of those fallen in the battlefields, and those who had become Turks[6] were not taken to exile. We had not been deported yet when caravans of refugees came to our town. Our Afyonkarahisar was connected to the Izmir station and Constantinople station, from where the railroad went into the depths of the country.

The exile started later from our area. There were Seljuks in our town. Their mosque was called tyulbé. The Seljuks tyulbé was in the Armenian district. One day, there was a fire there. The Armenians had assisted and the tyulbé was not burned down. That was why the Seljuks liked the Armenians. The Armenian women had gone and asked them for help. The Seljuk sheik had died. His son succeeded him. The Seljuk sheikh’s mother had said to her son: ‘I’ll curse my milk to you if you do not help these people. The Armenians have been entrusted to us. If we harm them, God will punish us.’

The Armenian women said: ‘They have taken away our men. Where shall we go with our children?’

During the First World War, soldiers were taken both from the Turks and the Armenians. So, during Hürriyet[7], all men were drafted into the army. My father was also taken into the Turkish army: that was the reason why they did not deport us. And many people were rescued by the Seljuks: they were not exiled. But others were. The Turks and the Chechens plundered them. They robbed them of their jewelry. That was why the Armenian women swallowed their gold coins in order that these would not be found. But the Turks cut open their bellies, even pregnant women’s, to find gold.

When there was a truce, our father took us, three brothers and a sister, to Izmir, to the American orphanage. In 1922, the Kemalists came there and occupied the city. Mrs. Vanet was our mistress. She was a very good woman. She adopted an Armenian girl and went to America. Rich Americans supported us. We were fifteen thousand Armenian orphans. In Izmir, there was the Mesropian School and its director was Andranik Karapetian.

The disaster in Izmir took place in 1922. The Kemalists came from Anatolia to Izmir; the mob filled in the town. First they surrounded Haynots – the Armenian quarter. We constructed barricades in front of the orphanage. Izmir was burning in flames when we, five orphans, escaped, threw ourselves into the sea and swam towards an Italian ship which took us to Pirea. Thousands of orphans were brought out and joined us. They took us all to the Isle of Corfu near the Adriatic Sea.

In 1923, the Italians began to bombard our orphanage; many were wounded. We were already grown boys, so they sent us to Cavala and Drama. I started to work as a shoemaker.

In 1932, a man by the name of Shahverdian came from Armenia and took us to Armenia. We were about fixe-six thousand Armenians. The ship sailed to Batoumi. At the beginning, I was in Stepanavan, Gyulagarak, and then I moved to Yerevan.

Later, after many years, I found out that they had killed all our relatives. They did not even reach der-Zor. My father had fallen victim near the Dardanelles, and my uncle ws kolled in an ‘Amele tabur’[8]. My sister had died of typhoid. The Turks had wanted to kidnap the two pretty daughters of our priest, Father Sahak. The priest had resisted. When he had seen that there was no way out, he had drunk the Afyon-Karahissar poison[9], which he had about him and had given the same to his daughters to drink: they died of the poison at the spot.”

Source: Svazlian, Verjiné (ed.): The Armenian Genocide: Testimonies of the Eyewitness Survivors. Yerevan: “Gitoutyoun” Publishing House of NAS RA, 2011, p. 382 f.