Located in the north-eastern part of the Erzurum province, in the upper reaches of the Chorokh (Grk.: Akampsis; Trk.: Çoruh) River, which flows through the kaza with two sharp turns, absorbing the small tributaries of Chorak and Chuyiruh.

Toponym

The name of the citadel and seat of the later Ottoman kaza derive from the medieval Armenian Baytbert (Բայտբերդ). In Movses of Khoren‘s History of Armenia the town is being mentioned as Բայբերդ (Bayberd; Western Armenian: Paypert). Movses asserts that the city’s ancient name was Smbataberd (‘Fortress of Smbat’), in reference to the Smbat I, founder of the Bagratuni dynasty.

The citadel and homonymous town were known under a variety of names during the Byzantine period; Procopius naming the city Baiberdon, meanwhile Kedrenos calling it Paiperte.(1)

Varieties of the toponym are: Baberd, Baberdz, Babert, Bayberd, Bayberdon, Bayberton, Bayburd, Bayburdi, Bayburt, Baypurt, Baytberd, Paypert, Payput

Population

According to the French geographer Vital Cuinet, the kaza Bayburt had a population of 58,313 in 1900.[2] On the eve of the First World War, there lived 17,060 Armenians in 30 localities of the kaza, maintaining 56 churches, three monasteries and nine schools with 844 students.[3]

The kaza was known for cattle breeding and cultivated good grain.

Settlements with Greek population

Παϊπούρτ(η) – Paypourt(i)

Καράγιασμαχ – Karayiasmakh

Κόσκιρι – Koskiri (Koçgiri)

Παλαιχώρ – Palaikhor

Πουλούλε – Poulele

Τουρνάκαγια – Tournakayia

Τσαμούρ(ε)α – Tsamour(e)a

Χαϊκια – Haykia

Χαλβά-Μαντέν – Halva-Maden

Χατράχ – Khatrakh(4)

History

The area of Bayburt was subsequently settled or conquered by the Cimmerians in the 8th century B.C., the Medes in the 7th century B.C., then the Persians, Pontos, Rome, the Byzantines, the Bagratid Armenian Kingdom, the Seljuk Turks, the Aq Qoyunlu, Safavid Persia, and then the Ottoman Turks. From c. 1243 to 1266, Bayburt was under brief control of the Georgian princes of Samtskhe. It has been ruled by the Ottomans since 1514.

The area was raided by the Safavids in 1553. Bayburt was captured by a Russian army under General Paskevich and its fortifications thoroughly demolished in 1829. It was the furthest westward reach of the Russians during that campaign. The bazaar remained poor and the town long lacked industry. Under the Treaty of Adrianople Russia returned the occupied Ottoman areas 1829. About 1000 Armenian families who helped the Russians, avoiding the revenge of the Turks, emigrated in 1829-1830 and settled in the Armenian region and in the province of Akhaltsikhe.

On 3 July 1916, Russian troops recaptured Baberd, but in 1918 it was again handed over to the Ottoman Empire.

Destruction

On 30 September 1895, 1400 Armenians were slaughtered in Bayburt by Turks and Laz. Many Armenians were forcibly converted to Islam.[5]

In February 1916, Greeks from Katrak and Koskiri (Koçgiri; both near Bayburt) were deported to Sivas.[6]

In 1918 Russia returned the area to the Turks. It was during those years that the Armenians of Bayburt, who at that time numbered about 10,000, fell victim to the genocide or were scattered to different countries.

In December 1921, Greek males of Kosma were deported to Erzurum, Bayburt and other destinations.[7] Also in 1921, Greek males between 12 and 70 years of age were deported from Meliananton to Sarıkamış, Erzurum, Erzincan, Bayburt and Karakilise.[8]

On 6 June 1922, the newspaper Protevousa informed its readers of the destruction of thirteen Greek villages in the district of Galliani, Kapiköy, and Livera, and the deportation of the locals to Bayburt.[9]

Raymond Kévorkian: Destruction in the Kaza of Bayburt / Papert in May-mid-June 1915

“To this northern kaza with its roughly 30 Armenian localities and a total Christian population of 17,060,86 the Young Turk government had sent one of its most faithful militants, Mehmed Nusret Bey, a native of Janina, to serve as the kaymakam of Bayburt.

The Special Organization, for its part, put its squadrons in the area under the command of Lieutenant Piri Necati Bey. This district, through which ran the roads leading south from the shores of the Black Sea as well as the main road between Erzincan and Erzerum, was cleansed of its Armenian population earlier than most others.

As early as 2 May 1915, the Armenian villages in the northern part of the kaza were set upon by bands of çetes. The next day, the military authorities issued an order to ‘remove’ the Armenian population from all areas within 75 kilometers of the border. The first to be arrested and murdered were the notables of the village communities. What gives a particular twist to the events of May–June 1915 is the fact that operations in this period were directly supervised by Bahaeddin Şakir, who traveled from Erzerum to Bayburt in order personally to establish the procedures to be used during the deportations and massacres, first in the villages and then in the cities and towns.

He had Nusret Bey appointed president of the deportation committee, which was made up of Piri Mehmed Necati Bey; Ince Arab Mehmed, a government official; Arnavud Polis, the police chief; Kefelioğlu Süleyman Paşazâde Hasib; Velizâde Tosun; Şahbandarzâde Ziya; Musuh Bey Zâde Necib; Karalı Kâmil; Kondolatizâde Haci Bey; and Ince Arab Yogun Necib.

The trial of those who organized and carried out the massacres in Bayburt, which was held in July 1920 before Court-Martial No. 1 in Istanbul, provides us with information that we lack in the case of the other regions of the vilayet of Erzerum. The testimony of Adıl Bey, a captain in the gendarmerie stationed in Erzerum, shows that the massacres in the kaza of Bayburt were organized by Bahaeddin Şakir, the ‘president of the Teşkilât-ı Mahsusa [Special Organization]’ and a member of the party’s Central Committee; Filibeli Ahmed Hilmi Bey, the party’s delegate in Erzerum; Saadi Bey, a nephew of the senator Ahmed Rıza Bey and a lieutenant in the reserve; and Necati Bey.

The verdict handed down by the court-martial states, finally, that the massacres perpetrated in this region were the first to be discussed and decided upon by ‘the headquarters [of the Central Committee] of the Union and Progress party’ and that they were organized under Bahaeddin Şakir’s authority.

In the course of this trial, it was established that Lieutenant Mehmed Necati voluntarily transferred most of the mobile battalions of the gendarmerie to the front so that he himself could escort the convoys of deportees. In other words, the Special Organization considered the gendarmes to be an obstacle to the realization of its plans. At their trial, of course, Necati and Nusret adamantly proclaimed their innocence of the crimes they were charged with. They were, however, contradicted by Salih Effendi, the commander of the brigade of the gendarmerie in Bayburt, who testified before the commission of inquiry that a few of his men had been charged with carrying out arrests of army deserters or draft dodgers. The gendarmes in the region had, however, not escorted the caravans of deported Armenians, who were taken in hand by Necati Bey. They never arrived in Erzincan.

Other witnesses, such as Hasanoğlu Ömer, who was responsible for provisions and supplies in Bayburt, declared before the commission that Kefalioğlu Kiaşif, a lieutenant in a labor battalion, Iliasoğlu Sabit, and others, deported the Armenians from Bayburt in several convoys: ‘At two hours’ distance from Bayburt, ‘they took the children aged between one and five from the convoys and brought them back to the town.’

Ali Esadoğlu Effendi, a native of Baştucar (in the kaza of Surmene), added that Nusret was a close friend of Tahsin Bey’s and that he sent 150 orphans to Binbaşihan, where he invited the inhabitants of the village to choose those they wished to ‘adopt.’

All reports concur about the fact that Deyirmendere, located on the first spurs of the Pontic Mountains to the north of the town, was the place where most of these deportees were put to death. It would thus appear that the CUP had from the outset planned to recover children of five and under in order to integrate them into the great Turkish family.

The age limit mentioned here suggests that the condition for this ‘integration’ was that the children be too young to remember their origins. Interestingly, Armenian women and children were sought-after commodities. When Armenians were rejected, what was rejected was their identity.

It should be noted that Nusret Bey, the 44-year-old kaymakam of Bayburt who ‘committed crimes during the deportation of the Armenians from his kaza,’ helped himself to the 24-year-old Philomen Nurian of Trebizond and her younger sister ‘Nayime’.

Accounts by survivors attest that Nusret sent the deportees to Binbaşihan and Hindihan, where he had all their money confiscated; that he was present while the massacres took place; and that, with the gendarmes’ help, he secured the prettiest girls and young women for himself and carried them off. Nusret nevertheless maintained that the convoys of deportees from Bayburt were sent to Erzincan. The court pointed out in response that they never arrived there.

The procedure employed here, at this experimental stage, was rather similar to the one that would be adopted in other areas in the weeks to come. The first concrete action taken was the arrest, on 18 May 1915, of the leading personalities of Bayburt – the primate, Anania Hazarabedian, as well as Antranig Boyajian, Hagop and Smpat Aghababian, Arshag and Manug Simonian, Ohannes and Serop Balian, Zakeos Ayvazian, Khachig Boghosian, Hagop and Aram Hamazaspian, Vagharshag Dadurian, Vagharshag Lusigian, Antranig Sarafi an, Krikor Keynageuzian, Hamazasp Shalamian, and 60 other people.

Those arrested were sent to the village of Tighunk, guarded by a squadron of çetes under Nusret’s personal command. There they were shut up in a stable belonging to the mufti, Kuruca Koruğ, where a squadron of Turkish and Kurdish çetes stripped them of their belongings. On 21 May, the kaymakam had them hanged to the beating of drums on the banks of the Jorok [Trk.: Çoruh].

On 24 May came the first attacks on the villages Aruk/Ariudzga (pop. 370), Chahmants (pop. 502), Malasa (pop. 380), Khayek (pop. 361), and Lipan. On 25 May, Tumel (pop. 204), Lesonk (pop. 981), and another ten or so villages were attacked; a total of 1,775 people were evacuated and led to the gorge of Hus/Khus. Here they were massacred, under Nusret’s and Necati’s direct supervision, by bands of çetes commanded by Huluki Hafiz Bey, Kasab [‘Butcher’] Durak, Derviş Ağa, Kasab [‘Butcher’] Ego, Attar Feyzi, and Laze Ilias. On 27 and 28 May 1915, the inhabitants of 24 more villages were evacuated and led in the direction of Hus/Khus, but were massacred further off, near the village of Yanbasdi.

According to the report of a survivor by the name of Mgrdich Muradian, the Turkish population of Bayburt was opposed to the deportation of the Armenians; the kaymakam is supposed to have had three Turks executed to bring people to reason.

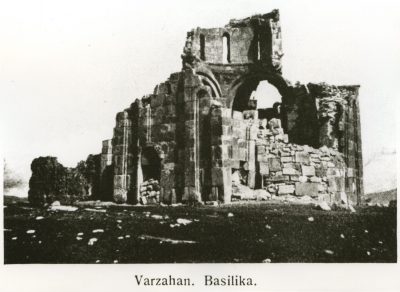

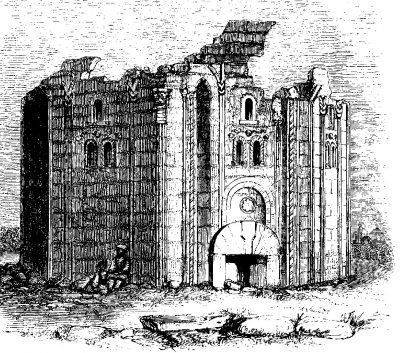

The first caravan nevertheless left Bayburt on 4 June 1915, followed by a second caravan on 8 June and a third on 14 June. In all, some 3,000 people were deported. As early as 11 June, İsmail Ağa, İbrahim Bey, and Pirı Mehmed Necati Bey set about destroying the monasteries of Surp Kristapor in Bayburt and Surp Krikor [Surb Grigor; Saint George] in Lesonk, after plundering them. The aim was doubtless to gain possession of the monasteries’ treasures, but also to set in motion without delay the effort to wipe out all traces of the Armenians’ millennial presence in the region, especially the superb architectural monuments of the early Middle Ages.

According to Mgrdich Muradian, who was in one of the convoys that left Bayburt in the first half of June, his convoy followed the road leading from Erzincan over the Kemah Bridge to Arapkir, as far as Gümuşmaden. There, Kurdish çetes began systematically slaughtering the deportees. A few women and children managed to make their way to a village lying between Arapkir and Harput, Khule kiugh (Huleköy). From there, Kurdish ağas took them to Dersim. In this way, 80 people escaped with their lives. They eventually found refuge in Erzincan after the Russian forces captured the city.

Keghvart Lusigian, who was probably in the same caravan as Muradian, reports that her group was taken to a place two hours distant from Bayburt; there the men were separated from the others and killed. In Plur, the convoy was attacked by Kurdish çetes, who slit the throats of the last men in the group, Hagop Aghababian, Zakar Sheiranian, and Keghvart’s brother Garabed Lusigian.

The çetes then robbed the deportees and abducted a number of young women. In Kemah, they put women, adolescent girls, and children in separate groups, which were then given as gifts to Turks who had come from Erzincan for the purpose. Four hundred women and girls were selected, but some of them succeeded in throwing themselves into the Euphrates.

According to Lusigian, some 300 women from Erzerum were ‘married’ to officers in Erzincan and another 200 were ‘married’ to government officials. She herself ‘belonged’ to a kadi [judge] by the name of Şakir. It seems that the stretch of the Euphrates near the Kemah gorge also served to drown 2,833 children from the kaza of Bayburt who were too old to be ‘adopted.’”

Excerpted from: Kévorkian, Raymond: The Armenian Genocide: A Complete History. London, New York: I.B. Tauris, 2011, pp. 300-303. https://www.aniarc.am/2015/04/11/the-kaza-of-bayburt-the-armenian-genocide/

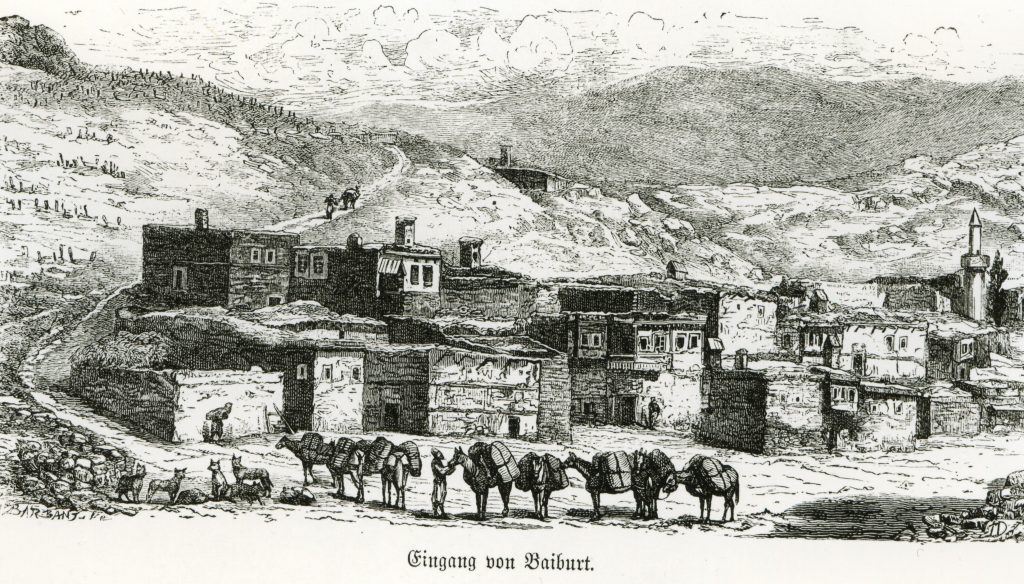

City of Bayburt

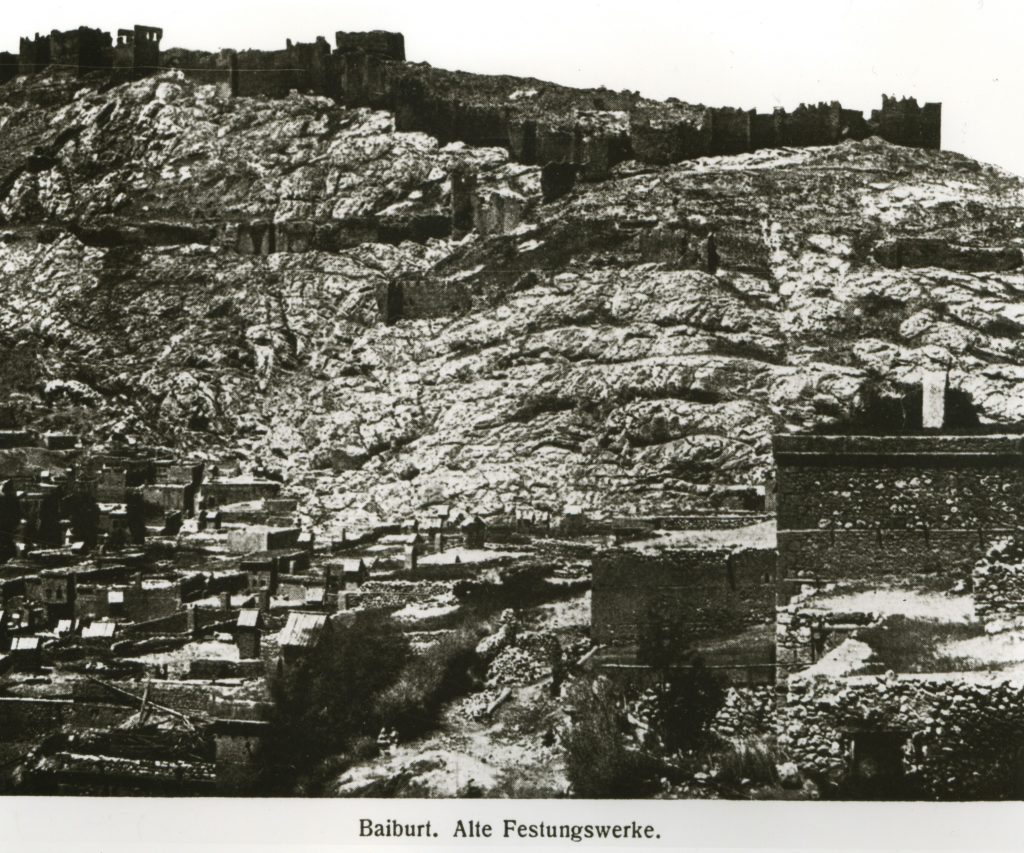

Situated in a fertile plain, the gardens of Bayburt spread mainly along the right bank of the Chorokh (Çoruh). Bayburt’s one-story houses were buried in gardens and orchards, they are mostly earthen. The fortress of Bayburt, which has been known since ancient times, is located near the sharp bend of the Chorokh, on an inaccessible hill.

Population

The existing data on the ethnic composition of the town’s population are largely inaccurate and contradictory. In 1800-1830, Bayburt had 14,000 inhabitants, of which 10,000 were Armenians, in 1830-1850 – 13,000, including 8,000 Armenians, in 1909 their numbers had decreased to 2,400 people (400 houses). In 1912 there were 500 houses, 360 of which were Armenians. According to archival data, in 1914 there were 450 Armenian farms in Bayburt with 2,500 inhabitants. In addition to Armenians, there small number of was a small number of Greeks. The Armenian neighborhoods were Antikeche, Kaler, Jazida, Jazizade.[9]

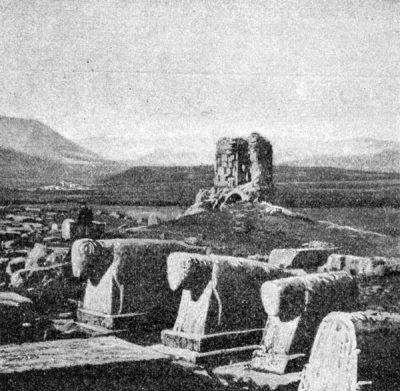

Prior to 1915, there existed five functioning Armenian churches (Surb Astvatsatsin, Surb Astvatsamayr, St. Archangel, Surb Nshan (Holy Cross), Surb Ohan) in the kaza, one of which was built in 1266, two Greek churches, numerous shrines, five mosques, and four Armenian cemeteries (14th and later centuries). The most famous of the Muslim mosques in the town of Bayburt is the Ulu Camii, a converted Armenian church. It used to be the residence of the Armenian bishop in the Middle Ages. Preserved are several Armenian manuscripts written in the 13th-17th centuries in Bayburt. On the eve of 1914, there were Armenian and Greek schools for boys and girls in Bayburt. The number of students in Armenian schools was 420, and the number of teachers was 14. Armenians are mainly engaged in agriculture, cattle-breeding, trade, handicrafts, especially jewelry and ironwork.

Tobacco from Trebizond was processed here. In the early 20th century, there were more than 500 shops and kiosks in Bayburt, as well as numerous outbuildings, mills, olive groves, leather, soap, and candle factories. In May-June, fairs were regularly organized in B for two weeks, with the participation of local merchants and craftsmen. There are healing mineral water springs 15 km from the town.

Notable Armenians

- Hovhannes XI (Çamaşırciyan): Armenian Patriarch of Constantinople between 1800 and 1801)

- V. Matenchyan (1880-1920): Literary critic, pedagogue

- Krikor Amirian (1888-1964): Revolutionary

History

Remains of cyclopean buildings indicate that Bayburt is a very old settlement. Located on the Silk Road and the navigable Chorokh River, the garrison city of Bayburt was ruled by many peoples, including Urartians, Armenians, Persians, the Roman Empire and the Seljuks. It was renamed several times during its history.

The town was the site of an Armenian fortress in the 1st century and may have been the Baiberdon fortified by the emperor Justinian. It was a stronghold of the Genovese in the late Middle Ages and prospered in the late 13th and early 14th century because of the commerce between Trebizond and Persia. It contained a mint under the Seljuks and Ilkhanids.

The Mongols were defeated here in 1364 by Alexios III, the Emperor of Trapezunt. In 1462, the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II fought here against the Turkish Akkoyunlu. In 1825, the city was completely destroyed during an invasion by the Russians, but was rebuilt.

Bayburt Castle stands on the steep rocks north of Bayburt. During the reign of the Armenian Arshakuni dynasty (1st-5th centuries) it belonged to the Bagratuni ministerial Dynasty, which fortified the fortress with new constructions and held it by the 9th, 10th, and 11th centuries. It was completely rebuilt by the Saltukid ruler Mugis-al-Din Tugrul Sah between 1200 and 1230, as attested by an inscription in the walls of the castle.

In 1271, the Venetian traveler Marco Polo passed by. Conquered in 1514, the Ottomans rebuilt the fortress in 1544 during the reign of Sultan Mehmet III. The massive size of its walls and the quality of its masonry place it amongst the finest of all the castles in Anatolia. The castle was inhabited till the destruction on 7 July 1829, during the Russo-Turkish War, when Russian troops blew up and occupied the fortress, which was severely damaged by a large fire and ceased to exist. In 1829, under the Treaty of Adrianople, Bayburt was returned to the Ottomans. At that time, 1,000 Armenian families emigrated from Bayburt and the surrounding Armenian villages and settled mainly in the Akhaltsikhe region. The situation of the Armenians worsened especially after the Russian-Turkish war of 1877-1878 and the Congress of Berlin (1878).