Toponym

The placename derives from Byzantine Derzene. The town and region were formerly called Mama Hatun, after the late 12th century female Saltukid ruler Melike Mama Hatun.

Population

At the eve of the First World War there lived 11,690 Armenians in 41 localities of the kaza, maintaining 36 churches, two monasteries, and 27 schools with an enrolment of 1,187 students.[1]

Today, the town Tercan has a large Kurdish population that is mostly Alevi as well as a significant Turkish Sunni population.

Notable Armenians

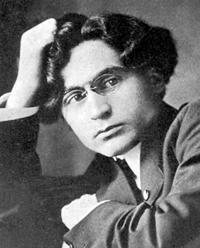

- Soghomon Tehlirian (Tehlerian; born in Nerkin Bagarij/Pakaric, 1896 – San Francisco, 1960): Avenger

“Not I am the Murderer!”

The Avenger Soghomon Tehlirian

Born on 2 April 1896 in the village of Nerkin (Inner) Bagarij (Բագառիճ; Trk.: Pakaric) in the Mamahatun/Tercan kaza of the Erzurum Province, Soghomon Tehlirian (Soġomon T’ehlirean – Սողոմոն Թեհլիրեան; also: Tehliryan; Soġomon T’ehlerean – Սողոմոն Թեհլերեան; 1897-1960) was raised in nearby Yerznka (Erzincan) since 1905, after his father was arrested and sentenced to six months imprisonment. During this time, the Tehlirian family moved to Erzincan, where Tehlirian received his initial education at the Protestant elementary school. After graduation at the Armenian Central Lyceum (Getronagan) of Constantinople, he went to study engineering in Serbia.

During the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, Tehlirian went to Russia and joined General Andranik Ozanian’s Armenian volunteer force, fighting alongside the regular Imperial Russian army against the Ottomans, while those family members who had stayed in Erzincan were deported in June 1915.

After the World War, Tehlirian learned in Constantinople at a lecture by Dr. Melkon Gülistanian that the original list of the Armenian elite arrested in the Ottoman capital on 24 April 1915, had been compiled by a certain Harutiun Mkrtchian for Bedri Bey, the president of the capital’s police force. Gülistanian was one of the few survivors of those arrested at the time.[2] In March 1919, Tehlirian shot Mkrtchian in Constantinople. This first assassination drew the attention of the clandestine Armenian Nemesis (Armenian: Vrej) network to Tehlirian, who was invited to Boston and put on Talat as the “number one” on Shahan Natali‘s hit list. On the late morning of 15 March 1921,Soghomon Tehlirian shot the former Ottoman Minister of the Interior (21 January 1913 to 4 February 1917), Minister of Finance (November 1914 to 4 February 1917) and head of government (Grand Vizier; 4 February 1917 to 8 October 1918), Mehmet Talat (1874-1921) on Berlin’s Hardenbergstrasse.

Vrej – Nemesis

Vrej was created in response to the failure of the Allies to bring the C.U.P. genocide perpetrators to justice, contrary to earlier announcements. Three months after the Ottoman court martial in Constantinople on 5 July 1919 sentenced the members of the Young Turkish War Cabinet to death in absentia, the 9th Party Congress of Dashnaktsutiun (Armenian Revolutionary Federation – ARF), the party then ruling alone in the Republic of Armenia (1918-1920), dealt with the question of retaliation in the fall of 1919. There are various accounts of the outcome. According to one variant, the 9th ARF World Congress at Yerevan passed a secret resolution called The Special Mission (Hatuk Gorts) to punish those mainly responsible for the Armenian genocide: “Between 1920-1922 the perpetrators were located and felled by the Armenian avengers.”[3]

Vrej was created in response to the failure of the Allies to bring the C.U.P. genocide perpetrators to justice, contrary to earlier announcements. Three months after the Ottoman court martial in Constantinople on 5 July 1919 sentenced the members of the Young Turkish War Cabinet to death in absentia, the 9th Party Congress of Dashnaktsutiun (Armenian Revolutionary Federation – ARF), the party then ruling alone in the Republic of Armenia (1918-1920), dealt with the question of retaliation in the fall of 1919. There are various accounts of the outcome. According to one variant, the 9th ARF World Congress at Yerevan passed a secret resolution called The Special Mission (Hatuk Gorts) to punish those mainly responsible for the Armenian genocide: “Between 1920-1922 the perpetrators were located and felled by the Armenian avengers.”[3]

The ARF dissidents’ intent on retaliation created a secret network named after the ancient Greek goddess of revenge, which was to implement the retaliation logistically and operationally. “Our organization had no extermination plan,” wrote the avenger Arshavir Shirakian in retrospect. “It inflicted punishment on individuals who had been tried in absentia and found guilty of mass murder. Armenian traitors topped our list.”[4]

The leadership committee of Operation Nemesis was initially headed by the former Ottoman Member of Parliament (1908-13) for Erzurum, Armen Garo (Garegin Pastermadjian – Գարեգին Փաստրմաճեան; 1872-1923), who became Ambassador of the Republic of Armenia to the USA in 1919. The planning and coordination of the “Special Mission” was the responsibility of the revolutionary and publicist Shahan Natali (also Natalie; i.e. Hakob Ter-Hakobian; 1884-1983).[5] Funding was provided by Aaron Sachaklian (1879-1964), the “financial wizard” of Nemesis: “… It can be said that Garo was the soul, Natalie the heart, and Sachaklian the head of Operation Nemesis.”[6]At the end of 1922, when the ARF had to move its headquarters to Bucharest after the Kemalists took the Ottoman capital, Operation Nemesis apparently ended.[7] Shahan Natali was removed from his leadership position at the 11th World Congress of the ARF in 1929.[8]

Tehlirian’s assassination of Talat, the “Number One,” was followed on 18 July 1921 in Constantinople by the assassination of Behbud (also: Bihbud, Pipit) Javanshir Khan, the leader of the Musavat Party and Minister of the Interior of Azerbaijan, when up to 30,000 Armenians were slaughtered in September 1918 after Baku was captured by Ottoman troops. Misak Torlakian (1889/90-1968), Jivanshir’s executioner, was arrested and beaten up by French security forces, but was later handed over to the British occupying forces, whose court acquitted him in November 1921,[9] as in the case of Tehlirian before, because of Torlakian’s disability of guilt.

Shortly afterwards, on 5 December 1921, the former Ottoman Grand Vizier (head of government) Sait (Said) Halim was shot dead in Rome by the young Arshavir Shirakian (1902-1973). Together with Aram Yerkanian (Yerganian; 1890-1934), Shirakian subsequently shot Cemal Azmi, the “Butcher of Trebizond,” and Bahattin [Bahaeddin] Şakir, who as a member of the C.U.P.’s Central Committee and a leading member of the Special organization was responsible for the extermination of Armenians in the Eastern provinces, in Berlin-Charlottenburg on 17 April 1922. The group’s plan was actually to eliminate the entire Ittihat leadership, which at the time had found shelter in Berlin. To this end, Hra(t)ch Papazian, disguised as a wealthy Turkish student, had already infiltrated Turkish circles in Berlin and informed his companions Natali and Shirakian daily.[10]

On 25 July 1922, Ahmet Cemal was gunned down in the Georgian capital Tbilisi directly in front of the headquarters of the Soviet intelligence service Cheka by the Armenian avengers Petros Ter-Poghosian, Artashes Gevorkian, and Stepan Tsaghikian (Ստեփան Ծաղիկեան- Step’an Caġikean, b. 1886-?).

Nevertheless, Tehlirian was neither a murderer nor a mere tool of the secret organization Nemesis. He was driven by an obsession to take revenge on the man he considered to be mainly responsible for the destruction of his family. During the genocide, Tehlirian had lost 85 members of his extended family.

The criminal case against Soghomon Tehlirian

Talat’s assassination by Tehlirian caused German judicial circles considerable embarrassment. On 25 May 1921, Gollnick, the Chief Public Prosecutor, addressed the Prussian Ministry of Justice in order to explain his reservations about the legal strategy:

It is to be feared that the (forthcoming) trial by jury (…) will escalate into a mammoth political case. (…)

First of all, we are sure to expect that the defense will argue on behalf of the accused that his was an act of heroism freeing Christian Armenians suffering under the Turkish yoke. (…) Perhaps the defense will even try to investigate the stance of the German government on the Armenian atrocities. (…) Comparing the Polish insurrection with the Turkish (action), especially (at this time), and in England, where (politics) lends a friendly ear to the Armenians, would be (most) undesirable, as long as the Upper Silesian problem (remains unsolved).

Of even greater concern from the political point of view is a line of inquiry during the trial, which would consider (Talaat) Pasha’s general political role and his German connections. Talaat was known to be the most reckless of all (representatives) with pro-German inclinations in Turkey, (and) actually not only in (Turkish) regions, but also beyond (Turkish) borders in all parts of the Islamic world. The (eyes) of the entire Islamic world will be focused on (this) trial. Public discussions about the trial would have multiple and significant political repercussions in Asia, (especially) on political relations between (Germany) and Ankara’s newly-formed government. (…)[11]

However, Gollnick did not prevail against the Foreign Office with his proposal to conduct the proceedings in camera. On 1 June 1921, a day prior to the trial, in a meeting with Baron von Thermann and Count Friedrich Wilhelm von Schulenburg as representatives of the German Foreign Office, the Foreign Office representatives, clearly deviating from earlier requests, announced that a request for public exclusion by the prosecutors would be less than desirable as it could not only fail but could make a bad impression on the public.[12]

Tehlirian was represented by three lawyers: the privy judicial authority, Dr. Adolf von Gordon (Berlin; 1850-1925), whom Natali described as “conservative, but very influential.”[13] Gordon’s partner, Justice Counsel Dr. Johannes Werthauer (1866-1938), was one of the most prominent lawyers of the Weimar Republic, whose citizenship was revoked by the National Socialists in August 1933 on their first list.[14] Tehlirian’s third criminal defense attorney was the Privy Counselor Dr. Theodor Hugo Edwin Niemeyer (1857-1939), “a man of European reputation, co-founder of the International Law Association and member of the Institut de Droit Internationale, which was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1904. In 1915 he founded the Journal of International Law. In 1917, on Niemeyer’s initiative, the German Society for International Law was founded, which was forced to dissolve in 1933.”[15]

Thanks to the intervention of the presiding judge and District Court director Dr. Erich Lehmberg, the prehistory of Tehlirian’s deed was discussed in detail during the trial, when the defendant reported on the massacre of his family and his own survival:

This was unusual, but Lehmberg – who was very familiar with Lepsius’ collection of documents on Germany and Armenia – apparently wanted to strike a major chord that gave Tehlirian’s ‘I was not a murderer’ a certain credibility right from the start. The core of Tehlirian’s statements about the annihilation of his family was known to Lehmberg, who repeatedly asked for details, through Lepsius’ collection of documents,[16] which contained comparable descriptions of the course of the massacres.[17]

The statements of the two Armenian witnesses and genocide survivors Christine Terzibashian (born Eftian, ca. 1894-1969) and Rev. Grigoris Palagian (Balakian; 1873-1934) supported Tehlirian’s statements. Terzibashian and her family were deported from Erzurum in July 1915 and were among the remaining survivors. The cleric Palagian was one of the few Armenians who survived, having been arrested in Constantinople on 24 April 1915, and then deported to Çankırı or Ayaş. After his training in Erzurum, Rev. Palagian had previously studied architecture in Germany and had written a paper on the monuments of Ani, the former capital of the Armenian kingdom of Shirak. He then became a member of the clerical council in Constantinople and its secretary and proved to be an important “leader and organizer” in times of persecution of the Armenians. In March 1915, he was put on the denunciation list of Harutiun Mkrtchian, sentenced to death but escaped execution. Rev. Palagian was 42 years old and prelate in Manchester at the time of the criminal trial against Soghomon Tehlirian. He has described his experiences not only as a witness during the trial, but also in his two-volume memoir The Armenian Golgotha.[18]

On 3 June 1921, after one and a half hours of deliberation, the twelve members of the jury acquitted Tehlirian. The spokesman did not give any contextual reason for the decision.

After his immediate deportation from Germany in 1921, Tehlirian returned to Serbia, where he lived with his Armenian wife in Belgrade until 1950. From there the couple moved to Casablanca. “Having been told by the ARF that Turkish agents were closing on him in 1956 he moved to the United States.”[19]

In San Francisco Tehlirian worked as a postal employee under the alias Saro Melikian. His younger son characterized him as follows:

He was the most gentle, mild man you could ever meet, almost naïve. Me and my older brother had to force him to tell us what happened. He never liked to talk about it. He was a man of very few words. He used to write poetry and draw very well.[20]

Raphael Lemkin and the Genocide Convention of the United Nations

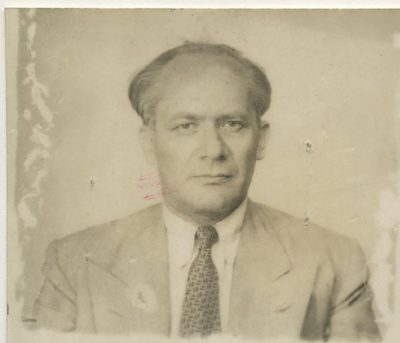

The criminal trial of 1921 left a deep impression on the Polish Jewish jurist Raphael Lemkin (1990-1959), who was born in what is now Belarus. Lemkin wrote about this key experience in his autobiography:

“The court in Berlin acquitted Tehlirian. It decided that he had acted under ‘psychological compulsion.‘ Tehlirian, who upheld the moral order of mankind, was classified as insane, incapable of discerning the moral nature of his act. He had acted as the self-appointed legal officer for the conscience of mankind. But can a man appoint himself to mete out justice? Will not passion sway away such a form of justice and make a travesty of it? At that moment my worries about the murder of the innocent became more meaningful for me. I did not know all the answers, but I felt that a law against this type of racial or religious murder must be adopted by the world.”[21]

In the dilemma between impunity and lynch law, Lemkin’s lasting and outstanding achievement was to have recognized the legislative gap that prevented state and major crimes such as that committed against Armenians and other Christians in the Ottoman Empire from being punished or even prevented. He heard from his Heidelberg law professor that there was no law to prevent crimes committed by a state against its citizens. Lemkin pointed out the legal inconsistencies: “It is a crime for Tehlirian to kill a man, but it is not a crime for his oppressor to kill more than a million men? This is most inconsistent.”[22]

Lemkin’s life’s work became the drafting and implementation of an international treaty on the prevention and punishment of genocide. The first attempts to introduce such a convention into the League of Nations failed in 1933[23], and it was only after another world war and genocide on an even larger scale that the United Nations adopted the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide in 1948, the essential parts of which were prepared by Lemkin. The definition of genocide contained therein is empirically based on the historical examples of the extermination of the Armenians in 1915/16, the so-called Simele massacre of Arameans and Assyrians in Iraq in 1933, and the extermination of European Jewry (Shoah) in World War II. As early as 1943, Lemkin had introduced the term genocide, which has been in international use ever since, into historical and legal literature. Until then, French publicists and British politicians such as Winston Churchill[24] or Lloyd George called the mass extermination of the Armenians in the late Ottoman Empire a holocaust[25] (Greek: “whole-burn sacrifice”).

Destruction

“The deportations began in these villages on 30 and 31 May [1915]. They were directed by the parliamentary deputy from Kemah, Halet Bey, the son of the former vali of Erzerum, Sağar Zade, who had organized squadrons of çetes made up of Muslims from Kemah and Erzincan areas as soon as the general mobilization was decreed. These bands, under the command of the chief of the Balaban tribe, Gülo Ağa, were placed under the joint supervision of the mutesarif of Erzincan, Meduh Bey, and the kaymakam of Tercan, Aslan Hafiz,

According to survivors’ reports, the men were massacred either where they were found or some 15 miles to the south in Goter/Gotır Köprü, where the squadron commanded by Gülo Ağa was waiting for them. Here they were stripped of their belongings, their throats were cut, and they were thrown into the Euphrates. Survivors from the villages of Pulk (pop. 778), Pakarij ([Bagarij] pop. 1,060), Sargha/Sarikaya (pop. 695), and Piriz (pop. 855) later affirmed that some of those who survived these massacres were driven to Erzincan and then on to the Kemah pass, where they were killed.”[26]

Report by the German Administrator in Erzurum (Max Erwin von Scheubner-Richter) to the Ambassador on Extraordinary Mission in Constantinople (Hohenlohe-Langenburg), Erzurum

„On 23 June 1915, the Armenian farmer, Garabeth [Karapet; Garabed] Hadji [Trk.: Haci] Oglu Goergian, from the village of Irdazur, 55 years old, presented himself at the local consulate [Erzurum]. Before the evacuation of the Armenians, this farmer delivered eggs and other products to the local consulate. He was wounded by a shot in the left hand during the massacre in the area around Mama Hatun [Mamahatun/Tercan]. He managed to escape and to reach the consulate. He reported the following on his experiences:

The inhabitants of 13 villages from the Passin [Trk.: Pasinler; Armenian: Basen / Pasen] and Erzurum plains were gathered, about 6-700 carts and 9-10,000 people. This included, among others, the people from the village of Padishvan on the Passin plain and from the villages of Umudum, Shipen, Kieselkilisse [Kızıkilise], Erginis, Khamshkavank, Kirsinkos and Irdarzur on the Erzurum plain. We marched to Mama Hatun via Yenikoy [Yeniköy] and safely reached the Euphrates Bridge. From Mama Hatun onwards we were accompanied by the Kaymakam with 10 gendarmes on foot and 20 irregulars and gendarmes on horseback. After we crossed the Euphrates, we entered the Tshividäh Mountains where we were suddenly shot upon from all sides while in a narrow pass. The Kaymakam ordered us to retreat, which we did. While we were again climbing up the Tshividäh Mountain, Kurds jumped out from the bushes and attacked us. Everyone ran in all directions, even the infantry ran away. Our head, however, was defended by some of the irregulars so that 100 carts and the largest part of the people were saved. Later on, we gathered together near the village of Karkin, after having taken 1 ½ days to reach it. The Kaymakam met us there and suggested taking another route, over the Kütür Bridge to Baiburt. Full of gratitude, we held a collection for the Kaymakam and gave him about 200 Ltq. When we reached the bridge, most of the people did not wish to continue. But the Kaymakam and the irregulars persuaded the people to continue on to Päräz [Perez]. The following morning, after having spent the night there, we walked on and by noon we reached the Euphrates. We camped here and were just eating when we were surrounded by Kurds … [illegible] on foot and attacked. Everyone fled, some of the people, including myself, saved themselves by crossing the river. Three people near me dropped: two were shot and the third had his abdomen slit open with a dagger so that his entrails hung out. Many of us drowned in the river. Those of us who saved themselves returned to Päräz, where we gathered in the church. We had not been able to take one single cart with us; we got away with only our lives. The night in Päräz passed without incident. The next morning the irregulars appeared and ordered us to gather on the threshing floor. We had hardly arrived before they started shooting at us. Some of us saved themselves by running towards the river; the rest ran back into the church in Päräz. The Armenians were then gathered together again, the women were separated and locked into a barn. Once again, the men were shot at. Those people who had run towards the river saved themselves by going to Mama Hatun. Kurds were also involved in this massacre, although none of them were Dersim Kurds. Women later turned up in Mama Hatun, who said they had been robbed of everything, even clothes. Many of them had been killed, many kidnapped. Those who were not robbed in Päräz were robbed while on the road. The Kaymakam had only accompanied them as far as the bridge and then turned back. While camping close to Mama Hatun, we received 2 sacks of bread. The next day the irregulars forced us to return to Päräz. Once again, not far from Mama Hatun, we were attacked, this time by camel drivers, emigrants [muhacirler] and irregulars. We dispersed, some of us towards the river and some towards town. Together with four other people I saved myself in running into a valley. 2 ½ hours from the place where we were attacked, we had to climb a mountain and had just reached its peak when the irregular following us caught up with us. He promised to protect us and wanted to bring us to the village of Ardash. On the way, he suddenly shot at my four companions and killed them. I was the last one he shot at and he hit me in the left hand. I fell to the ground and lay there. The irregular thought he had killed me and turned away. After lying there for 1 ½ hours, I saw the other bodies being robbed. I ran away and hid behind a tree. I only travelled at night, so that it took me three nights to get here. For two days I was well treated in the Kurdish village of Khon, where I rested. This was how I managed to enter Erzurum unnoticed, where I then sought refuge at the German consulate known to me.”[27]