Administration

In 1864, the region of Ayaş became a kaza in the sancak of Angora.

Destruction

“Ayaş, which (…) is located near the Sincanköy railroad station, 15 kilometers from the Armenian village of Stanoz and some 50 kilometers west of Angora, was chosen as the place of imprisonment for the Armenian political elite of Istanbul – some 120 to 150 people. The prisoners arrived in Ayaş in several waves, after a stay – short or long, depending on the prisoner – in Istanbul’s central prison.”[1]

Grigoris Balakian: The Tragic End of the Deportee Friends in Ayash

“While the rivers and tributaries of the Ankara province were filling with blood, and the valleys with unburied corpses, eight hours away in Ayash – a small country town and district center – the condition of our exiled comrades was no less tragic. After being transported to Ayash, these seventy-five were locked up in an old armory called Sare-Kushla [Yellow Barracks], at the far end of town; its shattered windows were boarded up.

Over the course of one month (…) thirteen lucky ones succeeded in returning to Constantinople, thanks to powerful intervention and generous bribes. Our comrades sent telegrams and letters to the minister of the interior [Mehmet Talat] and to influential Turkish friends, demanding justice in the name of the Ottoman Constitution. (…) Of course, all the petitions went unanswered. (…)

So well had the Ittihad Committee leaders played their role, and so successfully had they gained the blind trust of the Armenian revolutionary leaders, that the latter found themselves facing a great riddle that they were unable to solve. Alas, such blind faith cost the precious lives of one million innocent people.

These Armenian leaders had thought of the Ittihat leaders as their ideological comrades. In fact, they were no more than common criminals; only through audacity had they gotten their hands on the helm of the country – not to save the fatherland but to satisfy their personal ambitions and greed.

For the most part, those exiled to Ayash spent their last days in material privation. Of these, poor Shahrigian cried like a boy when he received five gold pieces in the mail from Constantinople. When his friends asked why he was so emotional, he said, ‘The person who sent me this money is the poor Greek washerwoman who lives in my house in Constantinople. What sacrifice has she made? Where did she find this sum, when she is so needy herself? The poor woman wanted to ease my grief.’ All our intellectuals, who would do any nation proud, not only suffered unspeakable mental anguish and emotional turmoil but had begun to wash their own laundry in order to save money. (…)

One black day Agnouni, Rupen Zartarian [Ruben Zardarian], Khajag, Minasian, Dr. [Nazaret Taghavarian] Daghavarian, and Haroutioun Jangoulian [Յարութիւն Կ. Ճանկիւլեան – Harutiun Djangulian; Jangülian] were ordered out of the armory at Ayash. The first four were distinguished Dashnak intellectuals; Daghnavarian was a former Hunchak and more recently an ardent Ramgavar [Democratic Liberal]; and Jangoulian was one of the old chiefs of the Hunchak Party, as well as the hero of the first civic protest at Kum Kapu [Kum Kapı] in 1891.

Under the strictest police supervision, these six were transported by rail toward Adana-Aleppo, supposedly to be tried before the court-martial in Diyarbekir. (…) On the road to Diyarbekir, a day’s journey from Ourfa, chetes [irregulars] that had been sent by the governor of Diyarbekir, Dr. Reshid, suddenly surrounded them. They were subjected to unspeakable tortures, then killed. (…)

During the horrible massacre of the Ankara Armenians in mid-August 1915, some of the exiles in Ayash were transported to the Ankara prison. One black day, together with a twelve-hundred-person caravan of native Ankaran Armenians, they were all killed in gruesome ways in a valley about four or five hours from the town.

Meanwhile, the rest of our exiled comrades in Ayash were martyred a few hours from there, on the famous mountain Kable Bel (…). The local Turkish villagers, having come from the surrounding areas at dawn, also took part in the massacre, using axes, hatchets [satr], hoes, rocks, and iron rods. (…) Eyewitnesses who miraculously survived recounted that the Turkish villagers from the vicinity of Ankara were wearing redingotes [frock coats], overcoats, jackets, and shoes taken from those they had killed, sporting the undeniable evidence of their participation in the blood fest. (…)”

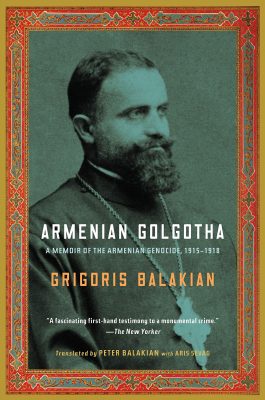

Excerpted from: Balakian, Grigoris: Armenian Golgotha: A Memoir of the Armenian Genocide, 1915-1918. Translated by Peter Balakian with Aris Sevag. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2009, pp. 82-95