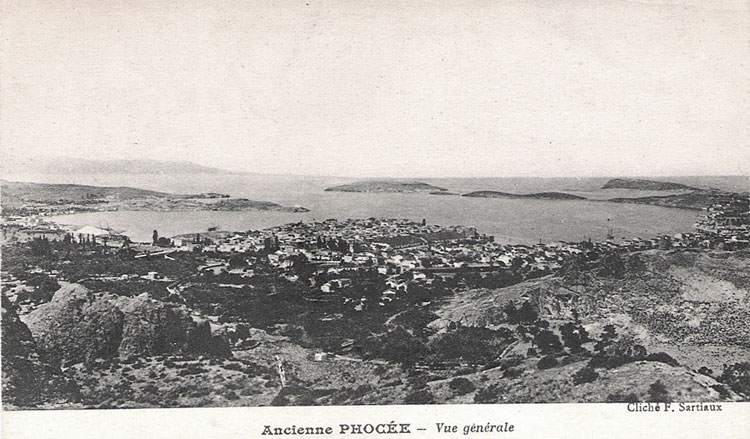

Foça is the successor settlement of the ancient and medieval Greek city of Phokaia (ancient Greek Φώκαια), also Phocaea (from the Latin form Phocaea; Galloital Foggia). Phocaea was located on the peninsula between the Gulf of Elaia and that of Smyrna. It was inhabited by Ionians, but was located in Aeolis.

Phokaia had two natural harbours within close range of the settlement, both containing a number of small islands, including the island of Bakchion, occupied by temples and palaces. Phokaia’s harbors allowed it to develop a thriving seafaring economy, and to become a great naval power, which greatly influenced its culture.

Greek colonists from Phocaea founded the colony of Massalia (modern-day Marseille, in France) in 600 B.C., Emporion (modern-day Empúries, in Catalonia, Spain) in 575 B.C. and Elea (modern-day Velia, in Campania, Italy) in 540 B.C.

Toponym

The name of the city derives from Greek founders of the ancient central Greek region Phokis. The Turkish form of the name Foca preserves the Italianized form of the name Foggia.

History

The ancient Greek geographer Pausanias says that Phokaia was founded by Phocians under Athenian leadership, on land given to them by the Aeolian Cymaeans, and that they were admitted into the Ionian League after accepting as kings the line of Codrus. Pottery remains indicate Aeolian presence as late as the 9th century B.C., and Ionian presence as early as the end of the 9th century B.C.

Herodotus, the ‘father of history’, who was born in nearby Halicarnassos, celebrated the Greek city-state of Phokaia for its resistance to the Persians in 500 B.C. According to him, the Phokaiaens were the first Greeks to make long sea-voyages, having discovered the coasts of the Adriatic, Tyrrhenia and Spain. Herodotus relates that they so impressed Arganthonios, king of Tartessus in Spain, that he invited them to settle there, and, when they declined, gave them a great sum of money to build a wall around their city.

Their sea travel was extensive. To the south they probably conducted trade with the Greek colony of Naucratis in Egypt, which was the colony of their fellow Ionian city Miletus. To the north, they probably helped settle Amisos (Samsun) on the Black Sea, and Lampsacus at the north end of the Hellespont (now the Dardanelles). However Phokaia’s major colonies were to the west. These included Alalia in Corsica, Emporiae and Rhoda in Spain, and especially Massalia (Marseille) in France.

Phokaia remained independent until the reign of the Lydian king Croesus (circa 560–545 B.C.), when they, along with the rest of mainland Ionia, first, fell under Lydian control and then, along with Lydia (who had allied itself with Sparta) were conquered by Cyrus the Great of Persia in 546 B.C., in one of the opening skirmishes of the great Greco-Persian conflict.

Rather than submit to Persian rule, the Phokaiaens abandoned their city. Some may have fled to Chios, others to their colonies on Corsica and elsewhere in the Mediterranean, with some eventually returning to Phokaia. Many however became the founders of Hyele (later Ele, Elea), around 538-535 B.C.

In 500 B.C., Phokaia joined the Ionian Revolt against Persia. Indicative of its naval prowess, Dionysius, a Phokaiaen was chosen to command the Ionian fleet at the decisive Battle of Lade, in 494 B.C. However, indicative of its declining fortunes, Phokaia was only able to contribute three ships, out of a total of “three hundred and fifty-three”. The Ionian fleet was defeated and the revolt ended shortly thereafter.

After the defeat of Xerxes I by the Greeks in 480 B.C. and the subsequent rise of Athenian power, Phokaia joined the Delian League, paying tribute to Athens of two talents. In 412 B.C., during the Peloponnesian War, with the help of Sparta, Phokaia rebelled along with the rest of Ionia. The Peace of Antalcidas, which ended the Corinthian War, returned nominal control to Persia in 387 B.C.

During the Hellenistic period it fell under Seleucid, then Attalid rule. In the Roman period, the town was a manufacturing center for ceramic vessels, including the late Roman Phocaean red slip.

Phokaia was given to the Genoese around 1275 as a Byzantine fief in gratitude for their assistance in the reunification of the Byzantine Empire after the 4th Crusade. Subsequently, it was an important trading port, mainly thanks to the rich alum deposits of the region. The alum mines had been given to the Genoese brothers Manuele and Benedetto Zaccaria (the Genuese ambassador to Byzantium) as early as 1267. Benedetto Zaccaria, who received the town as a hereditary lordship. His descendants amassed a considerable fortune from his properties there. The Genoese retained control of the city even during the Ottoman period through the lease of 1275. Another important Byzantine fief to the Genoese was the nearby island of Lesbos, which was given as a dowry to the Gattilusio family at the marriage of Francesco I Gattilusio and Maria Palaiologina, sister of the Byzantine emperor John V Palaiologos, in 1335. The Gattilosios’ possessions grew by the islands of Imbros, Samothrace, Lemnos and the city of Aenos. From this position they were heavily involved in the mining and distribution of alum, which was used for textile production and was a profitable raw material for Genoese merchants.

Phokaia remained a Genoese colony until it was taken by the Ottomans in 1455. It is a titular see of the Roman Catholic Church.

In 1914, Phokaia was the location of a massacre against ethnic Greek civilians by Turkish irregular bands.

Population

The kaza Foça belonged to the Greek Orthodox Diocese of Ephesos, which comprised 85 communities with 164,467 inhabitants.[1] In the town of Phokaia, at the beginning of June 1914, lived almost 8,000 inhabitants, mostly Greeks, not counting the Greek refugees from the kaza of Smyrna who arrived at that time.[2] The Turkish population of Phokaia was about 400. [3]

Notables

- Theodoros of Phokaia was an architect of ancient Greece who worked in the late 5th and early 4th centuries BC.

Destruction

“In early June 1914, Başı Bozuk [irregulars] raided villages north of Smyrna, now Izmir. The Greek population fled to nearby Phocaea. At that time, just under 8,000 people, mostly Greeks, lived there. On June 12, gunmen broke into Greek houses there and shot the inhabitants. Coincidentally, a French archaeological team was present to assist the town’s inhabitants. Their eyewitness account aroused great interest in France, because the archaeologists were also excavating a piece of the French past here: Greek settlers had founded the colony of Massalia, later Marseille, from Phocaea in the 7th century B.C.

The German ambassador Hans von Wangenheim and his American colleague Henry Morgenthau reported unanimously that about fifty people had been killed in Phocaea, including a priest. After the sacking of the city, the remaining inhabitants were put to flight, many escaping by boat to nearby Greek islands. Archaeologist Charles Manciet reported how the city was subsequently looted. One hundred camels were loaded with the villagers’ belongings, he said.”[4]

“Violent persecutions occurred in this Diocese (eighty-five Communities, 164,467 inhabitants); murders took place all over the country and the inhabitants were kept in a constant state of uneasiness. The policy followed by the C.U.P. and its agents completed in 1914, the destruction premeditated by them.”[5]

“OLD FOGGIA [Phokaia].— On the 23rd May, 1914, the Chief of Gendarmerie of Menemen, Talaat Bey, visited this community, and having come to an understanding with the sub-governor and the Turkish notables, and drawn up the plan of destruction, undertook a trip to the surrounding Turkish villages, and gave the Turks an outline of the plan of destruction agreed upon. On the 31st of May, 1914, the village was surrounded at night by hordes of armed Turks from the neighbouring heights ; the attack on the village then began. The plundering lasted all the night through and continued till mid-day the next day.

The fury of the Turks against the Christians knew no bounds. The Mayor, Hassan Bey, massacred with his own hands his partner Dimitrios, his wife and two children, also the Kehaya, Hadja Keramida, as well as his wife and three children, killed Ath. Tutundji, Dimitri Tabaki and his father-in-law. He killed the daughter of Emmanuel Kouyoumdji, after having violated her, and cut the throat of Sophia Ghounari and her four children. Alti Parmak Hassan killed Stavros Manoglou and Ath. Koumarianos.

Ali Bey, the director of the salt works of Phocoea, had the apothecary Papacostas and his niece cut to pieces, after having violated the latter. The tobacco Mudir, Ibrahim Effendi, murdered Basile Theodoracoglou, his nephew Panayioti, and his brother, and a host of others.

The church of Saint Eirene was entirely plundered, and the altar desecrated. The cruel invaders climbed up the belfry and threw the cross down, after which a ‘muezzin’ (Turkish preacher) sang a ‘hymn of thanksgiving’ in honour of the conquest of the town.

The day after the catastrophe a cargo boat, carrying many thousands of Phocoeans including 1,000 children, left the port for Salonica. They were all in a lamentable condition.”[6]

The Last Day of Phocoea

“On the 12th of June [1914], towards half past six in the evening, I was working in the road leading from Phocoea to Menemen, when all of a sudden to my surprise I saw a long train of people with their luggage coming along apparently in flight. I learnt that they came from Guerenkeuy [Gerenköy] to seek refuge in Phocoea, after having been plundered by the Turkish bands. The next day I was busy with a survey in one of the oldest streets of Phocoea. The inhabitants were in a state of great anxiety. Everyone expected an imminent catastrophe. I witnessed the great panic. The words ‘they are coming’ went from mouth to mouth, the street full of women and children rang with cries of consternation. Every one hastened to shut himself up in his home and barricade his door. In a few minutes the street was deserted. The panic was so great that I was carried away by the crowd of fugitives at a distance of twenty paces from my tripod.

Shortly after calm returned, but the fright of the population was such, that at mid-day, about 1,000 inhabitants embarked on fishing boats and went to Mitylene. We, Mr. Sartiaux and myself, were very astonished to see persons abandoning all their property before any enemy was in sight. The news of the approach of a band of armed Turks was successful. From that moment we began to realise the gravity of the situation. We were four Frenchmen, Mr. Sartiaux, the assistant of Mr. Carlier, Mr. de Andria and myself. After a short consultation between us we decided to call on the Caimacham [kaymakam], and ask him to take the necessary measures for our protection. The Caimacham, thinking we were afraid for ourselves, offered to give us shelter in his official residence. We refused, and declared to him that we held him responsible for whatever might happen. He then gave us each a gendarme for the protection of our four houses.

We reached our homes and there made four French flags, which we hoisted over the doors of our houses. Our doors being wide open, a crowd of Christians took refuge within, bearing whatever precious object they could save. Thus we succeeded in giving shelter to 700 to 800 souls.

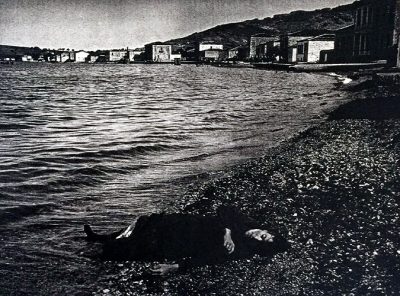

During the night the organised bands began to plunder the town. At day-break brisk firing started in front of our houses. Mr. de Andria, Mr. Sartiaux and I, hastened outside only to witness one of the most horrible sights. This band was armed with Gras (old rifles) and cavalry carbines. A house broke into flames. The Christians hastened to the quay in search of boats in which to embark. But not a single one had remained overnight in the port. Cries of terror mingled with the report of the guns. The panic was such that a woman and her child were drowned in shallow water only sixty centimetres deep. Mr. Sartiaux was the witness of a horrible sight. A Christian, with his wife and daughter, was in his house. The brigands tried to enter it. The head of the family spread his arms to prevent them from entering, and received a bullet shot from a Gras in the abdomen, after which he tried to make his escape to the sea, but he had only gone a few paces when a second bullet finished him. His corpse remained two days on the beach. His daughter, terror stricken, sought refuge in one of our houses, leaving her mother to be murdered in her house by the brigands.

Two large transports happened by mere chance to be in the port. We succeeded, all too slowly, to embark, those who escaped being in small groups. What would have happened if the two ships were not there? Such was the hurry of the inhabitants to embark that several boats sunk owing to the weight of the passengers. The bandits, pretending to search for arms, plundered the fugitives of whatever was left to them. They snatched and pulled away the luggage and even the mattresses from old women. At the sight of this I remonstrated with the officer of the gendarmerie, who was impassively looking on, and told him that unless he put a stop to this I would take a gun and fire upon these marauders. This declaration was sufficient to put an end to the acts of brigandage, and the refugees were allowed to depart in peace and quietness. The brigands, however, broke open the houses and carried away their booty, loaded on horses and donkeys, and even camels. Three thousand persons had been able to embark that day on the two steamers, which left for Mitylene. A great portion of the population still remains.

The night passed uneasily for the Greeks. The next day plundering continued regularly and methodically in all the houses. Presently, the wounded began coming to us. In the absence of medical assistance, I took charge of them until we could see them off to Mitylene. I noticed that, with the exception of two or three, the majority of the wounded were quite old people. Among them also were old women of ninety with bullet wounds. It was simply a massacre.

On the following days, numerous families that had hidden in the mountains came to us for protection. We sent for the officer of the gendarmerie at once, of whom we demanded two gendarmes to go to the aid of those poor people, and escort them to Phocoea. He did nothing in the matter and up to this day we are ignorant of the fate of these poor creatures. An old paralytic man was found in his bed by the brigands, and also put to death in cold blood.

Troops were sent from Smyrna to maintain order. Soldiers patrolled the streets with a view to keeping order, instead of which they also took to plundering. We saw an instance of this on the 17th of the same month when we asked two gendarmes to escort a Christian to his home, in order for him to take away some things he wanted. Unfortunately, these very gendarmes, who were supposed to defend him against all aggression, were the first to strip this unfortunate man of everything he possessed, i.e., the sum of Fr.4.25. The destruction was complete. Every door was broken open. Whatever the brigands could not carry away was destroyed, so that the town of Phocoea, once so bright, is now a dead city.

There is no doubt whatever that the plundering of this town was an organised plan, which aimed at the expulsion of the rayas (Greek Ottoman subjects) from the sea coast. It is not possible that the invading brigands could have possessed so many firearms if they had not been distributed to them beforehand.

No resistance was offered on the part of the inhabitants of Old Phocoea; they were the victims of a massacre.

We now read in the papers official communications to the effect that order has been established, and that in the regions we mention no one need have any apprehension as to one’s life and fortune.

As a matter of fact, order exists because there is not a single inhabitant left in the place. Also there is no danger to property either, it all being safely in the hands of the brigands.” [7]

“Mr. E. Whittal, a British resident of Smyrna, was an eye-witness of the following episode at the time when the armed brigands were pillaging the town of Old Phocoea. A young woman had jumped into a boat full of Christian fugitives. A brigand hastened to take her out of the boat, but he did not succeed in carrying away his prey ; on the contrary he was caught hold of by a firm hand, thrown to the bottom of the boat, carried away to Mitylene and delivered up to the authorities there. They took off his coat, under which he wore a gendarme’s uniform, and found <£200 in his pocket.

There is no doubt whatever from existing evidence that the Government officials were the real authors of the destruction of Old Phocoea.”[8]

On the night of the 12th of June 1914, Turkish irregulars raided the town of Old Phocaea (Gr: Παλαιά Φώκαια) and began a pillage and massacre of the town. The massacre lasted 24 hours. Many of the Greek inhabitants fled by boat to neighboring Mytilene. The Greeks of Phocaea returned to their homes in 1919-20 after the Ottoman defeat in WW1, but were expelled again in 1922.

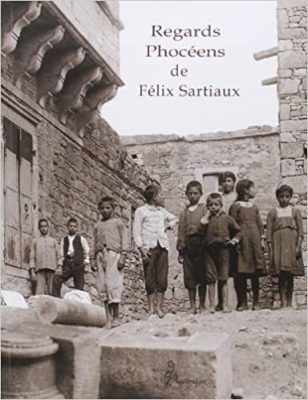

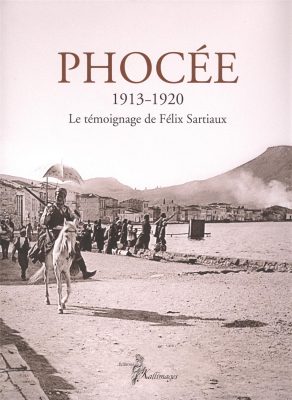

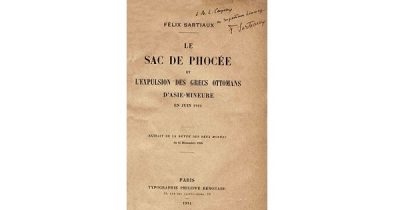

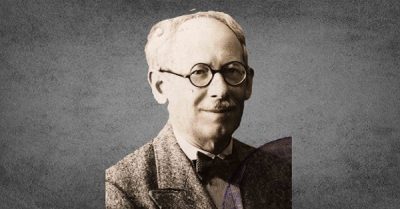

“The Events of 1914”: The Testimony of Félix Sartiaux