The Province

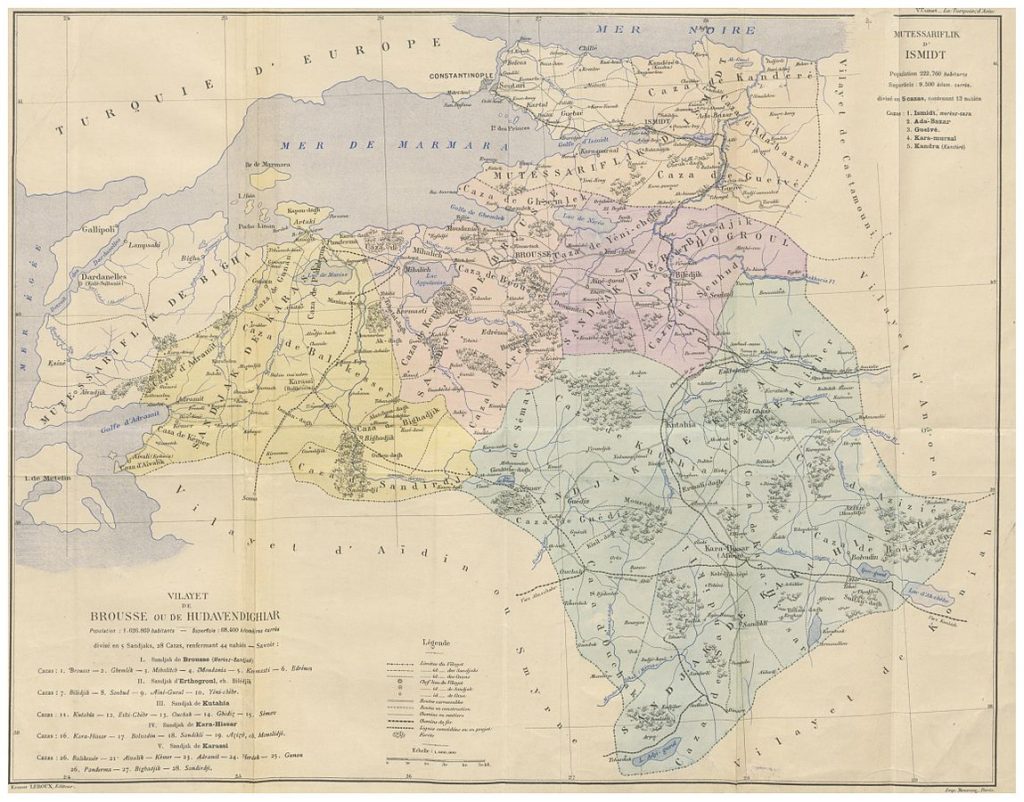

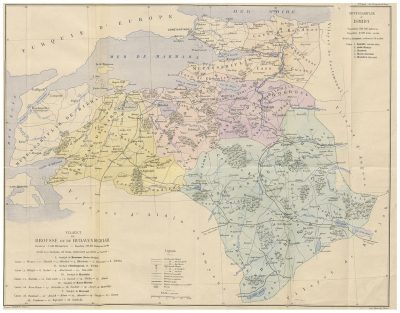

With 68,000 square kilometers, five sancaks as well as the mutesarrifliks Izmit (11,130 square kilometers) and Kütahya, the Vilayet Bursa/Prousa/Hüdavendigâr in the northwest of Asia Minor belonged to the extensive provinces of the Ottoman Empire. The history of this sultanate is closely connected with the region: Here the Ottoman Empire emerged from one of the many Oghuz beyliks (principalities) that had formed in Anatolia after the Seljuk invasion in the 11th century; some of them were in alliance with the Byzantine Empire, but most were in opposition to it. The dynasty, which was formed here in the late 13th century with the Oghuz tribal leader Ertuğrul (1198-1261 or 1262) and his son Osman I (1258-1326), used the region for their failures and attacks on Byzantium. Correspondingly, the first residences of the rising Ottomans were established here in quick succession: Söğüt and Yenişehir (1299-1326), followed by Prousa (1326-1368), which the Ottoman conquerors called Bursa.

The area, which is very varied in terms of its landscape, also includes the ancient regions of Bithynia, Phrygia and Mysia, which in turn are closely linked to the history of early Christianity in Asia Minor, as the history of the cities of Nikomedia and Nikaia proves. Inhabited mainly by Greek Orthodox Christians in the Middle Ages and early modern times, the Ottoman province of Bursa became an immigration area in the 16th and early 17th centuries for persecuted Christians – Greeks and especially Armenians – from the regions fought over by the Ottomans and Iranians, and from the 19th century onwards also for Muslim refugees from the Russian dominion and the Balkans. The result was an ethnically and religiously highly diversified population that was susceptible to conflict.

The Toponym

Although the Roman writer Plinius states that the city of Prusa was founded by Prousias (d. 182 B.C.), the king of Bithynia, the possibility of a native Anatolian name cannot be ruled out. The person name of Prousias is probably the Persian equivalent of the Firûz. The Brusa format is recorded immediately after the Turkish conquest in 1326. Until the beginning of the 20th century, the toponym Brûsa / Burûsa was used. Until 1924, the province and city of Bursa was named Hüdavendigâr ( (خداوندگار, from Persian ‘God’s gift’) in honor of the Ottoman ruler Murat I.[1]

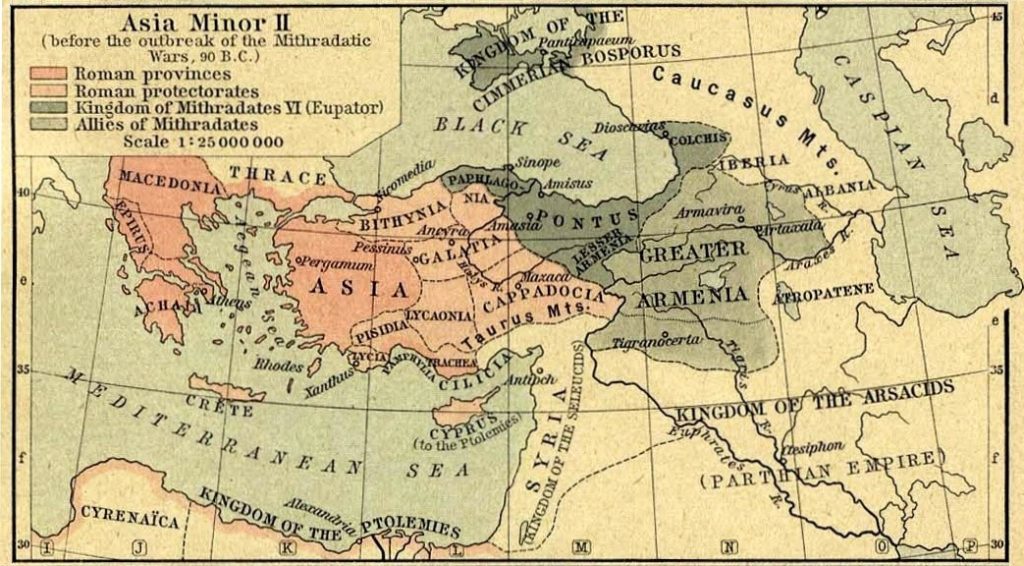

Bithynia

Situated in the very Northwest of Asia Minor, the region of Bithynia was adjacent to the antic provinces or kingdoms of Paphlagonia and Pontos in its east, Galatia in its south and Thrace in its northwest. Bithynia stretches from the southern coast of the Black Sea and the southern Marmara coast. Since 297 B.C., when the Bithynic ruler Tsipoitis (Grk.: Ζιποίτης; * 356 B.C.; † 280 B.C.) took the title of Basileios, Bithynia has had its own era, the Bithynic (or Bosporan/Pontic) era. In the year 64 A.C. it formed, together with Pontos, the province Bithynia et Pontus, which became an Imperial Roman province in 159 A.C., lasting until 295 A.C. In Ottoman times, Bithynia consisted of the province of Bursa, the mutesarriflik (sancak) of Izmit, which corresponded with the Orthodox Christian diocese of Nicomedia, and the region of Iznik, or Nikaia (Nicaea) in Greek, which represented another Orthodox diocese and had been the seat of two Ecumenical Councils of 325 and 787.

The ‘Silk and Faience Province’

The economic characteristic of the Bursa province was the cultivation of olives, vegetables and poppy (including opium production) as well as the breeding of silkworms and silk production; in the period 1888-1905 three quarters of the silk producers in the Bursa province were Greeks or Armenians.[2] According to a French military source, there were 42 functioning silk-mills in Bursa before the war, but only 12 in 1919, for “lack of labor-force” and because the cocoon production had “fallen off by 50%”.[3]

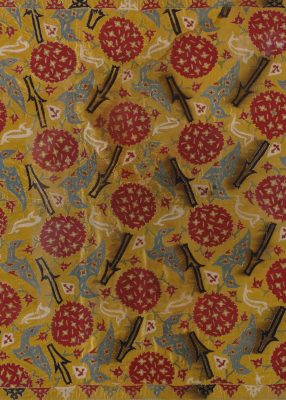

The production of painted faience products in the towns of Nikaia (Iznik) and Kütahya dates back to the antique period and is explained by the rich clay deposits in the surrounding area. After Nikaia, Kütahya was Ottoman Turkey’s most important center of ceramic production. While Nikaia mainly supplied the capital Constantinople, Kütahya produced mainly for the Christian middle class. The heyday of tableware and tile production in Nikaia was in the 16th century, followed by Kütahya in the 18th century.

Christian Population

With 1.3 million inhabitants, the province of Hüdavendigâr was the second most populated Ottoman province in the early 1890s – after the Vilayet Aydın with 1.39 million. According to the Turkish scholar Servet Mutlu, however, the population of Hüdavendigar Province fell drastically from 1,454,294 (1897) to 616,227 (1914) after the separation of the administrative units of Karesi and Karahisar-ı Sahip.(4)

As a result of intensive migration processes, the influx of Armenians since the late 16th century and Muslim ethnic groups from the Balkans and the Caucasus since the 18th century, the province of Bursa was an ethnically and religiously heterogeneous province at the turn of the 20th century. Among the Christian population groups, the Greek Orthodox Christians (‘rumlar’) outnumbered the Armenians by about two thirds: The Greek Orthodox Diocese of Prusa (Bursa), comprising 14 communities, had a population of 27,524 residents. A ‘Greek census’ for 1910-12, quoted by Wikipedia, mentions 262,319 Greek inhabitants of the entire Bursa Province.

As a result of the long and devastating Ottoman-Iranian fights over Armenia during the 16th and early 17th centuries, there was a massive immigration of Armenian peasants to Bithynia between 1590 and 1608. These immigrants originated from Akn, Arabkir, Sivas, Kemah and Erzurum. According to statistics compiled by the Armenian Patriarchate at Constantinople, the vilayet of Bursa had an Armenian population of 82,350 in the early 20th century. The Annuaire Oriental mentions more than 90,000 Armenians in the vilayet prior to World War I.(5)

WW1 Deportations from and to the Bursa Province

Already in March 1915, leading Ottoman Greeks were deported from various regions of the Empire – Eastern Thrace, Pontos, Constantinople – as part of an eliticide. The Hellenic Legation to Constantinople reported: „Up to the 8th of the current month, over 200 leading men of Constantinople had been expelled to Bilejik [Bilecik], Yeni-shehir and other parts of the interior of Asia Minor.”[6]

Since June 1915, more Greek Orthodox residents were dispersed among Turkish villages.[7] During the deportation of the Greek inhabitants of the Marmora islands in the beginning of June 1915, the inhabitants of the Island of Kalolimnos “were compelled, within a few hours, to abandon their island, without being able to take anything with them, and were sent to the villages of Michalitsi and Terbekioi [Terbeköy] near Broussa, suffering terribly from hunger. The number of the Greeks deported was about 1,440.”[8]

In July 1916, the governor of the Bursa Province, Midhat, ordered that the residents of the Greek villages Arvanitohori (district Kadıköy/Chalcedon [Χαλκηδών; today Eskiköy]), Neohori (Ano Neochori; Tr: Yukarıyapıcı), Eligmi and Messopolis should be distributed among Turkish villages at a proportion of ten percent. This included in part the Greek Orthodox population of the Yalova District in the Nikomedia Diocese that was either exiled to Greece or deported and dispersed in the Bursa District under the pretext of supplying the British submarines with benzine.[9]

Overall, seven Greek towns and villages were destroyed during WW1 in the district of Bursa.[10] According to a ‘rough estimate’ in 1918, 14,634 Greeks were deported from the district of Bursa (Prousa) and 4,176 from the district of Izmit (Nikomedia).[11]

“’All Armenians must be deported,’ the vali of the Bursa province declared, ‘without regard for gender, age and health.’ During the postwar trials, a prosecutor accused the secretary, Midhat, of going out of his way to ensure immediate removal of the sick, who were usually exempted from initial deportation orders. Per local directives, Armenians’ property would be used to pay their debts to merchants and suppliers and otherwise would be sealed away. Their houses would be rented out. The deportees were given three days to prepare for departure. They sold what they could; heirlooms went for a pittance. Officials told the deportees that they would be settled in Konya, but at this point well-founded rumors held that, from there, they would continue on foot to Deir Zor. The expulsions kicked off on August 18, with about 1,800 Armenians loaded onto 500 ox carts. More would be dispatched in the days that followed.

At the beginning of September Dr. Wilfred Post, another American physician working at the hospital in Konya, encountered ‘perhaps 5,000 exiles’ from Bursa. They camped in fields near the rail station, begged in the streets, and waited for a train. The deportees told Post that the authorities seemed intent on starving them to death: ‘Within two weeks the Government had made two distributions of bread, neither of them sufficient for more than one day, and had given nothing else.’ The deportees met further abuse on arrival in Konya, according to Post. ‘I myself saw police beating the people with whips and sticks when a few of them in a perfectly orderly way attempted to talk to some of their fellow-exiles on the train, and they were in general treated as though they were criminals.’ At Çay, sixty miles northwest of Konya, Post observed ‘perhaps a couple of thousand’ en route. ‘Here the men and women were together, and the Turks had not succeeded in carrying off more than two girls. By keeping constant guard, the Armenians, although unarmed, had been able to frighten the assailants away.’ Still, there was ‘great suffering, followed by sickness and some deaths, especially among the children. A good many of the people had gone insane.’

(…) According to Talât’s summaries, 66,413 people were deported from Bursa vilayet during the war, and fewer than 3,000 Armenians remained afterward. Only about 10,000 of the deportees were alive in 1917.”[12]

Report of Dr. Herbert Schwörbel, Dragoman (interpreter) of the German Consulate at Saloniki, 2/19 August 1915

“On my return from Aivali, which took me via Soma-Panderma-Brusa-Gemlik-Bazarkeuy (Bazarköy) to Yalova, I had the opportunity to witness the Armenian expulsions that were just beginning. According to the order of the central government in Constantinople, the Armenians were only allowed to take what they could carry with them, so that apart from their landed property, all their movable property had to be left behind. In larger towns like Brusa, the Armenians were able to sell at least some of their possessions, albeit at ridiculous prices, but in the open countryside and in the smaller towns this was also impossible due to the lack of solvent buyers. It should be remembered that the Armenian population was usually only given 24-48 hours to vacate their homes.

I have personally seen thousands upon thousands of Armenian women, children and old people being driven out of their houses and across the country road in the blazing heat of the sun with butt blows. Apart from clothes and small bundles, they had nothing with them. Especially terrible was the sight of the many pregnant women and women with very small babies, mostly only a few months old. On the way from Bazarkeuy to Yalova I saw two terribly mutilated bodies of Armenians lying in the ditch. Turkish soldiers passing by told me that there were a number of other corpses lying in the bushes. I don’t believe the Turks’ claim that the slain were Armenians who had resisted, since all the Armenians who were reasonably strong had been either imprisoned or assigned to road construction battalions for some time already. From male Armenians I have seen only old people and children everywhere.

From Turkish officials and officers I heard everywhere only cynical remarks about the fate of the expelled Armenian population. They all frankly stated that the only reason the Armenians were taken to the interior was to make them disappear there.

Especially in the Vilayet Brusa, where there are many prosperous, well-maintained Armenian villages, the lack of Turkish human material is likely to cause great damage to the country’s cultures. Likewise, the wholesale and retail trade, which was often in the hands of the rich Armenians, especially in the Vilayet Brusa, is likely to be destroyed for a long time to come.”

Source: Political Archives of the German Foreign Office (PA/AA), File Turkey (Akte Türkei), No. 168, Vol. 14, Vol. 15, No. 552, A, 26689, quoted from: Konstantinos Fotiadis: Der Genozid an den Pontosgriechen: Unveröffentlichte Documente aus den Archiven der Außenministerien Deutschlands, Österreichs, Italiens und des Vatikan. Bd. 12. (Athens), Herodot, 2003, p. 97f.

The Armenian People: Report (Summer 1918)

Report by Pastor Count von Lüttichau on his personal observations and conclusions during the summer of 1918

(…)

The extent of the catastrophe.

It is of no significance whether the figure given for the total losses of the Armenians is placed at one million (Consul Roessler) or two million (Christoffel), because surely there was never really any authentic information concerning the figure for the size of the Armenian population. The figure cited by Preacher Ehmann in Mezré – 1 ½ million – is estimated as being the closest to the truth. Far more important than the total figure, which is hard to check, is the percentage determined in the individual areas. In the eastern provinces, that is excluding Constantinople and Smyrna and other places in western Turkey, 80 – 90% of the entire population and 98% of the male population is no longer alive. These figures are probably correct. They can be checked town by town and correspond to my personal impression and observations. I met many boys and quite a few old men. I very seldom saw men at the height of their vigour, who stood out by their very existence. In Constantinople itself almost all of the Armenians were spared; the same applied for Smyrna. On the other hand, they were driven out of almost all the smaller towns and villages in western Turkey (for example, in Brussa, Ismid, Adapazar, Bardisag [Bardizag, Partizak – Պարտիզակ; in Turkish: Bahçecik], Jenidje [Yenice] and others), in European Turkey out of Rodosto, Adrianople and so on, so that one may say that, taking into account the Armenians who were left in the capital, in total at least 80% of the population was annihilated. This does not exclude the Catholics and Protestants; rather, it includes them.

The decree in favour of Catholics and Protestants.

The famous decree that ordered these two groups to be spared – the successful result of diplomatic attempts on the part of the Holy See and the papal delegates in Constantinople, and the Imperial German Embassy – was held back for a notoriously long time, as for example in Malatia, until these people had also been annihilated. The implementation of governmental decrees in the interior is left completely to the tyranny and the unscrupulousness of the public authorities. Control at a later stage is not possible. Apparently, the decree was not meant seriously, but represented a kind of pay-off for the bothersome grumblers, rather like baksheesh, without which the Oriental cannot exist. The fact is that Catholics and Protestants also suffered namelessly. There were a great many martyrs among them.

(…)

Source: Political Archives of the German Foreign Office (PA/AA), http://www.armenocide.net/armenocide/armgende.nsf/$$AllDocs-en/1918-10-18-DE-001?OpenDocument

Bursa and Izmit in 1921

“Amid ‘scenes of confusion, panic and terror’ the Christians of Izmit— 21,000 Greeks and 9,000 Armenians— escaped as the Turks advanced on the town at the end of June [1921]. Thousands of farm animals, driven to Izmit by Greeks from surrounding villages, ended up dead on the shoreline: ‘exposed to the blazing sun and without food,’ they drank sea-water. The townspeople feared massacre and fled, by sea, to Volo, Tekirdağ [Rodosto] , Constantinople, and the Aegean islands. In Bursa missionaries reportedly found eight hundred Greek and Armenian girls aged ten to sixteen who were raped and then ‘stamped by [the Turks] on the forehead with burning iron as a sign of their dishonor.’

While some western observers viewed the Turkish campaign in Izmit as ‘retaliation’ for Greek atrocities that spring in the Yalova-Izmit area, others, probably most, framed it differently: ‘The Turks are carrying out the extreme Moslem doctrine of the book or the sword’ that is, conversion or death, ‘and are pursuing a definite policy of clearing their territories of all Christian populations.’ It is possible that both views were to some degree correct, the Greek atrocities explaining the timing of the Turkish atrocities, while ideology provided a popular justification for the campaign.

As with the destruction of the Armenians during the Great War, the expulsion and murder of the Anatolian Greeks was in part driven by the enticing vision of plunder.”

Source: Morris, Benny; Ze’evi, Dror: The Thirty Year Genocide: Turkey’s Destruction of Its Christian Minorities, 1894-1923. Harvard University Press, 2019, p. 414