Toponym

Constantinople was founded as Byzantion (Greek Βυζάντιον). As early as the 10th century, Greeks also referred to the city as Bulin and Stanbulin, derived from Polis for ‘The City’. The Turks called it Istanbûl / استنبول already in the Rum Seljuk Sultanate and in the early Ottoman Empire. After 1453, under the Ottomans, the city was officially called قسطنطينيه Ḳusṭanṭīniyye. Istanbul was an alternative name.

It is still called ‘The City’ (η Πόλη – i Póli) or Constantinople (Grk.: Κωνσταντινούπολη – Konstantinoúpoli) by Greeks today. Constantinople is also often referred to in traditions as the City of the Seven Hills, by analogy with Rome. In Ottoman Turkish, Constantinople was also paraphrased as درسعادت (Der-i saadet) – The Gate to Bliss.

Administration

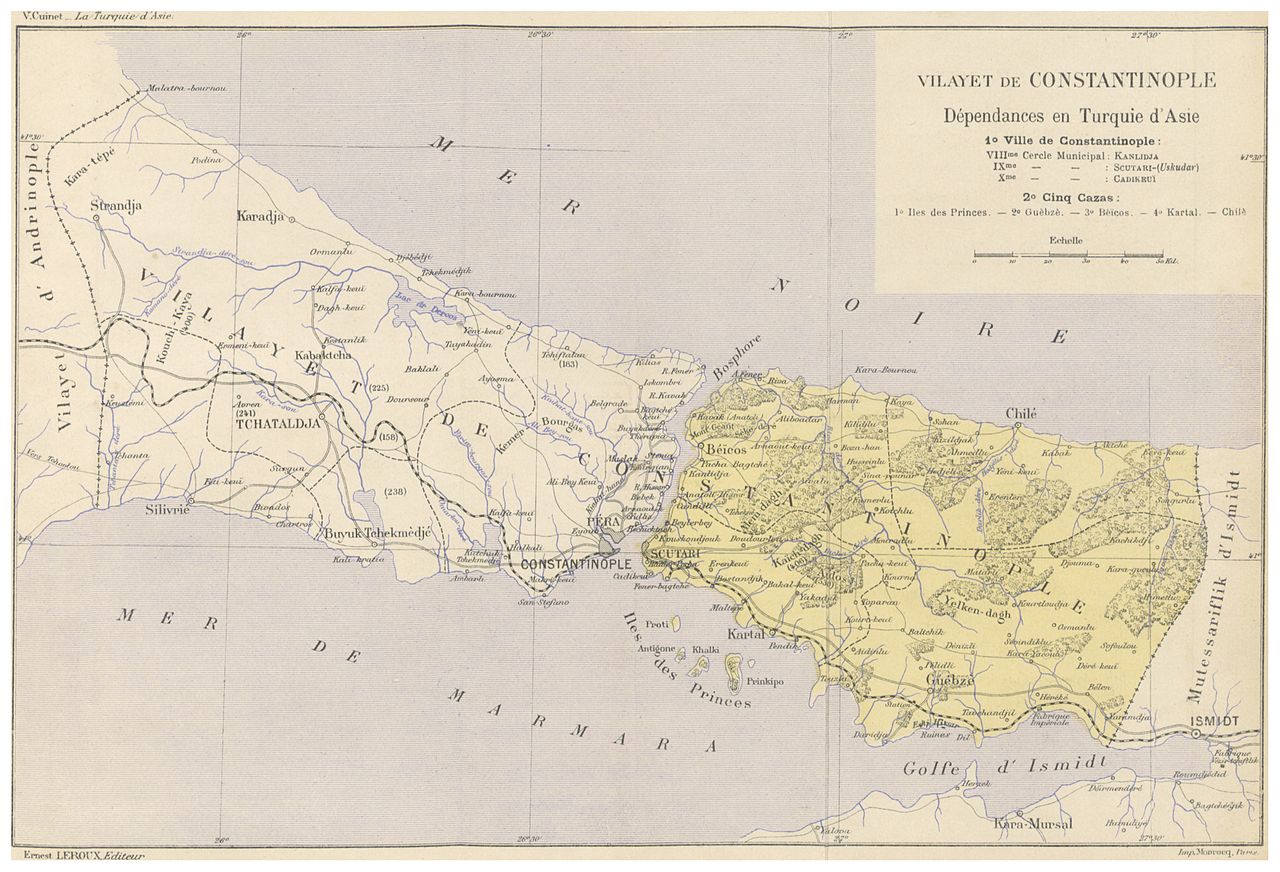

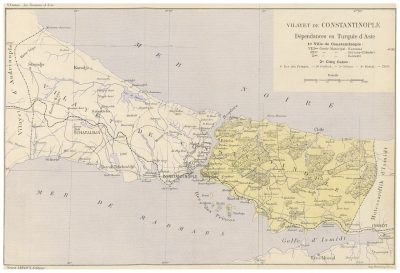

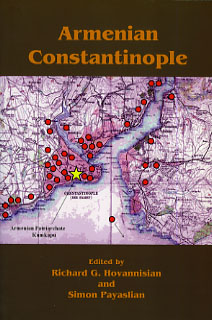

Covering a territory of 11,800 square kilometers, this province existed from 1878 to 1922, comprising the four sancaks of Stambul (kazas of Fatih-Sultan-Mehmet, Eyüp, Kartal, Prince Islands), Pera (kazas of Pera, Galata, Yeniköy), Scutari/Üsküdar (kaza of Beykoz) and Büyükçekmece (kaza of Çatalca).

Population

According to official Ottoman statistics in 1914 there lived 560,434 Muslims in the Province of Constantinople, 205,752 Greeks, 82,880 Armenians and 52,126 Jews.[1] As a result of the high level of migration to the Ottoman capital and its environs, the number of unreported cases among the capital’s population may have been particularly high. Moreover, official statistics have been distorted by the population policy effort to maximize the number of Muslims and, conversely, to make the number of non-Muslims appear low.

The Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople reported the number of Armenians before the First World War as 163,670, of which 161,000 were in the sancak of Constantinople and 2,670 in the sancak of Gallipoli / Gelibolu. Overall, they maintained a total of 53 churches and 64 schools with 25,000 students.[2]

History

The city of Byzantion, founded by Dorian colonists from Megara around 667 B.C., was elevated to the capital of the Roman Empire by Constantine the Great (reigned 306 to 337 A.D.) and renamed Constantinople after this first Christian ruler. As the example of Constantine, who himself came from present-day Niš in central Serbia, shows, the rulers of Rome and its Byzantine successor state were by no means consistently ethnic Latins or Romans, but belonged to a multinational, Hellenistically educated and, since Constantine, Christian elite.

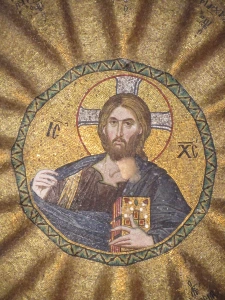

The Byzantines referred to themselves as Romans (Ῥωμαῖοι, Rhōmaîoi, contemporary pronunciation: Romaei) until 1400, then increasingly as Greeks (Έλληνες, Héllēnes/Éllines). The today common name Byzantine Empire is of modern origin. Contemporaries spoke only of the Vasilía ton Romäon (“Empire of the Romans”) or the Romaikí Aftokratoría, the “Roman Self-Rule.” According to their self-image, they were not the successors of the Roman Empire, but they were the Roman Empire in itself, since, according to them, there was only one empire under two emperors as long as both parts of the empire existed. In terms of state law, this was indeed correct, since Byzantium continued to exist in an intact state reminiscent of late antiquity, which only gradually changed and led to a Greekization of the state under Herakleios. Under this ruler, since the turn of 600, the Middle Greek, phonetically almost identical to today’s Greek, replaced Latin as the official language. Greek was already the language of the church, literature and all commercial transactions. The peculiarity of the Byzantine Empire was its unique mixture of Roman state, Greek culture and Christian faith (George Ostrogorsky).

After the conquest of Constantinople by the Ottoman Turks, refugees brought their scientific and technical knowledge and the ancient writings of Greek philosophers to Europe, where they contributed significantly to the development of the Renaissance.

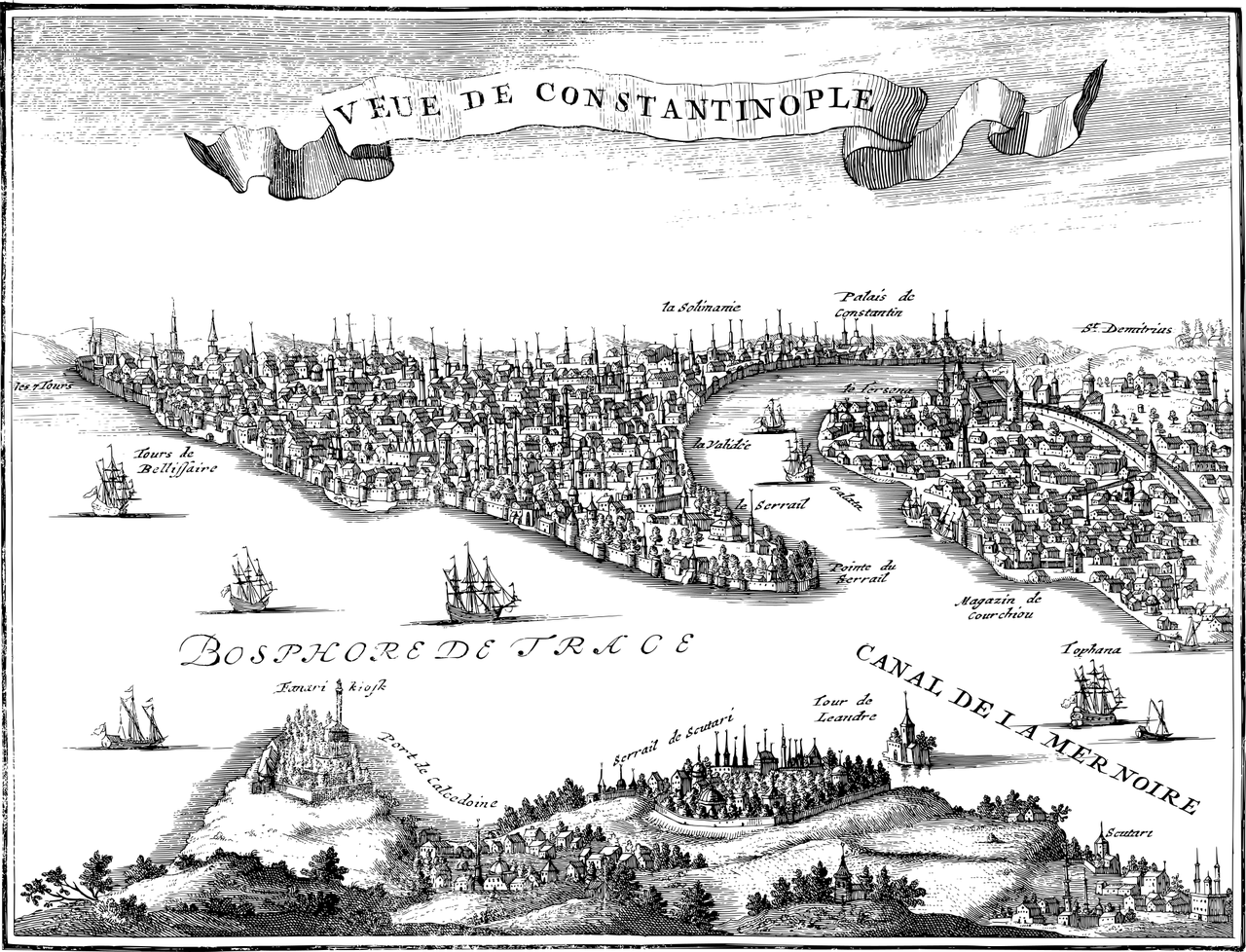

Byzantine Capital

Within three weeks of his victory at Chrysopolis (Scutari; mod. Üsküdar) in September of 324 A.D., where Constantine I finally defeated his opponent Licinius, the “foundation rites of New Rome were performed, and the much-enlarged city was officially inaugurated on May 11, 330. It was an act of vast historical portent. Constantinople was to become one of the great world capitals, a font of imperial and religious power, a city of vast wealth and beauty, and the chief city of the Western world. Until the rise of the Italian maritime states, it was the first city in commerce, as well as the chief city of what was until the mid-11th century the strongest and most prestigious power in Europe.

Constantine’s choice of capital had profound effects upon the ancient Greek and Roman worlds. It displaced the power centre of the Roman Empire, moving it eastward, and achieved the first lasting unification of Greece. Culturally, Constantinople fostered a fusion of Oriental and Occidental custom, art, and architecture. The religion was Christian, the organization Roman, and the language and outlook

Greek. The concept of the divine right of kings, rulers who were defenders of the faith—as opposed to the king as divine himself—was evolved there. The gold solidus of Constantine retained its value and served as a monetary standard for more than a thousand years. As the centuries passed—the Christian empire lasted 1,130 years—Constantinople, seat of empire, was to become as important as the empire itself; in the end, although the territories had virtually shrunk away, the capital endured.

Constantine’s new city walls tripled the size of Byzantium, which now contained imperial buildings, such as the completed Hippodrome begun by Septimius Severus, a huge palace, legislative halls, several imposing churches, and streets decorated with multitudes of statues taken from rival cities. In addition to other attractions of the capital, free bread and citizenship were bestowed on those settlers who would fill the empty reaches beyond the old walls. There was, furthermore, a welcome for Christians, a tolerance of other beliefs, and benevolence toward Jews.

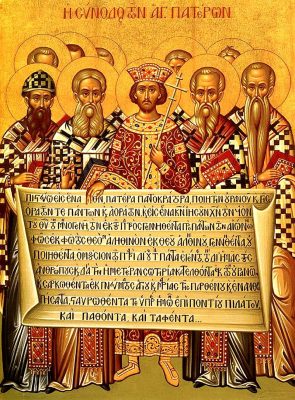

Constantinople was also an ecclesiastical centre. In 381 it became the seat of a patriarch who was second only to the bishop of Rome; the patriarch of Constantinople is still the nominal head of the Orthodox church. Constantine inaugurated the first ecumenical councils; the first six were held in or near Constantinople. In the 5th and 6th centuries emperors were engaged in devising means to keep the Monophysites attached to the realm. In the 8th and 9th centuries Constantinople was the centre of the battle between iconoclasts and the defenders of icons. The matter was settled by the seventh ecumenical council against the iconoclasts, but not before much blood had been spilled and countless works of art destroyed. The Eastern and Western wings of the church drew further apart, and after centuries of doctrinal disagreement between Rome and Constantinople a schism occurred in the 11th century. The pope originally approved the sack of Constantinople in 1204, then decried it. Various attempts were made to heal the breach in the face of the Turkish threat to the city, but the divisive forces of suspicion and doctrinal divergence were too strong.

By the end of the 4th century, Constantine’s walls had become too confining for the wealthy and populous metropolis. St. John Chrysostom, writing at the end of that century, said many nobles had 10 to 20 houses and owned 1 to 2,000 slaves. Doors were often made of ivory, floors were of mosaic or were covered in costly rugs, and beds and couches were overlaid with precious metals.

The population pressure from within, and the barbarian threat from without, prompted the building of walls farther inland at the hill of the peninsula. These new walls of the early 5th century, built in the reign of Theodosius II, are those that stand today.

In the reign of Justinian I (527–565) medieval Constantinople attained its zenith. At the beginning of this reign the population is estimated to have been about 500,000. In 532 a large part of the city was burned and many of the population killed in the course of the repression of the Nika Insurrection, an uprising of the Hippodrome factions. The rebuilding of the ravaged city gave Justinian the opportunity to engage in a program of magnificent construction, of which many buildings still remain.

In 542 the city was struck by a plague that is said to have killed three out of every five inhabitants; the decline of Constantinople dates from this catastrophe. Not only the capital but the whole empire languished, and slow recovery was not visible until the 9th century. During this period the city was frequently besieged—by the Persians and Avars (626), the Arabs (674 to 678 and again from 717 to 718), the Bulgars (813 and 913), the Russians (860, 941, and 1043), and a wandering Turkic people, the Pechenegs (1090–91). All were unsuccessful.

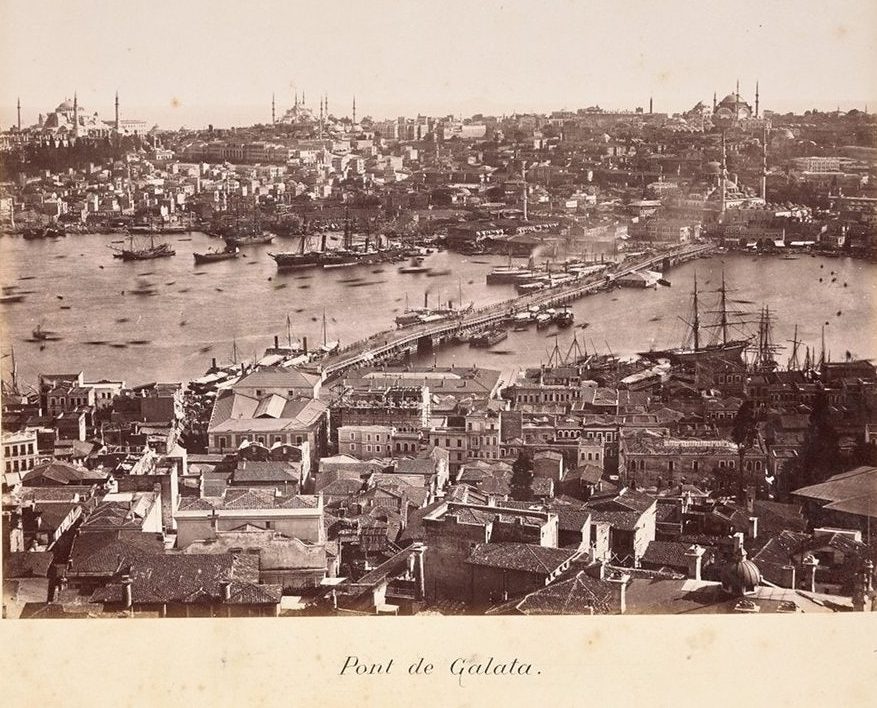

In 1082 the Venetians were allotted quarters in the city itself (there was an earlier cantonment for foreign traders at Galata across the Golden Horn) with special trading privileges. They were later joined by Pisans, Amalfitans, Genoese, and others. These Italian groups soon obtained a stranglehold over the city’s foreign trade—a monopoly that was finally broken by a massacre of Italians. Not for some time were Italian traders permitted once more to settle in Galata.

In 1203 the armies of the Fourth Crusade, deflected from their objective in the Holy Land, appeared before Constantinople—ostensibly to restore the legitimate Byzantine emperor, Isaac II. Although the city fell, it remained under its own government for a year. On April 13, 1204, however, the Crusaders burst into the city to sack it. After a general massacre, the pillage went on for years. The Crusading knights installed one of themselves, Baldwin of Flanders, as emperor, and the Venetians—prime instigators of the Crusade—took control of the church. While the Latins divided the rest of the realm among themselves, the Byzantines entrenched themselves across the Bosporus at Nicaea (now İznik) and at Epirus (now northwestern Greece). The period of Latin rule (1204 to 1261) was the most disastrous in the history of Constantinople. Even the bronze statues were melted down for coin; everything of value was taken. Sacred relics were torn from the sanctuaries and dispatched to religious establishments in western Europe.

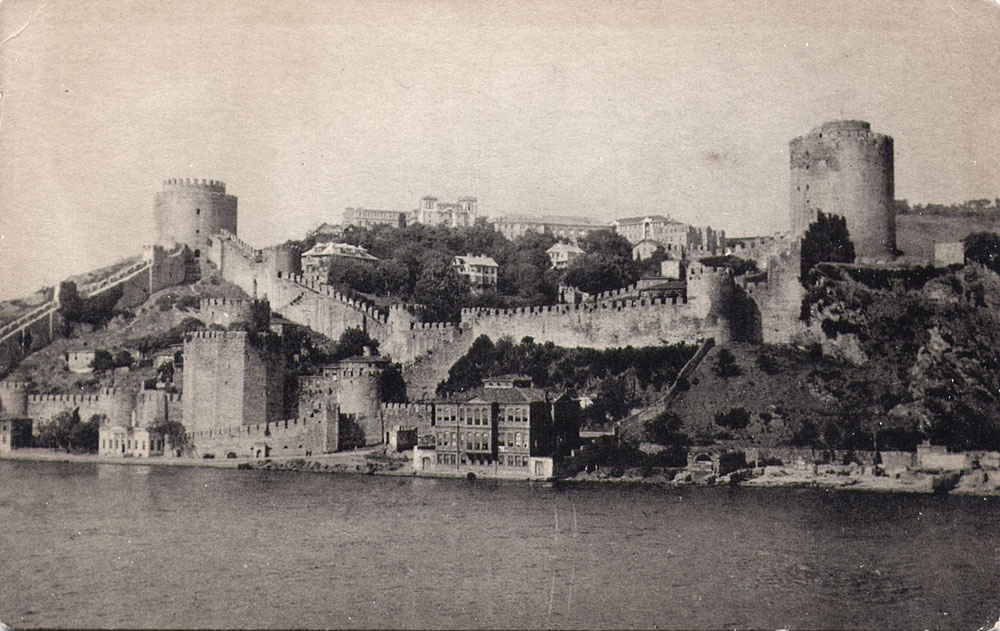

In 1261 Constantinople was retaken by Michael VIII (Palaeologus), Greek emperor of Nicaea [Trk.: Iznik]. For the next two centuries the shrunken Byzantine Empire, threatened both from the West and by the rising power of the Ottoman Turks in Asia Minor, led a precarious existence. Some construction was carried out in the late 13th and early 14th centuries, but thereafter the city was in decay, full of ruins and tracts of deserted ground, contrasting with the prosperous condition of Galata across the Golden Horn, which had been granted to the Genoese by the Byzantine ruler Michael VIII. When the Turks crossed into Europe in the mid-14th century, the fate of Constantinople was sealed. The inevitable end was retarded by the defeat of the Turks at the hands of Timur (Tamerlane) in 1402; but in 1422 the Ottoman sultan of Turkey, Murad II, laid siege to Constantinople. This attempt failed, only to be repeated 30 years later. In 1452 another Ottoman sultan, Mehmed II, proceeded to blockade the Bosporus by the erection of a strong fortress at its narrowest point; this fortress, called Rumelihisarı, still forms one of the principal landmarks of the straits. The siege of the city began in April 1453. The Turks had not only overwhelming numerical superiority but also cannon that breached the ancient walls. The Golden Horn was protected by a chain, but the sultan succeeded in hauling his fleet by land from the Bosporus into the Golden Horn. The final assault was made on May 29, and, in spite of the desperate resistance of the inhabitants aided by the Genoese, the city fell. The last Byzantine emperor, Constantine XI (Palaeologus), was killed in battle. For three days the city was abandoned to pillage and massacre, after which order was restored by the sultan.

Ottoman Capital

When Constantinople was captured, it was almost deserted. Mehmed II began to repeople it by transferring to it populations from other conquered areas such as the Peloponnese, Salonika (modern Thessaloníki), and the Greek islands. By about 1480 the population rose to between 60,000 and 70,000. Hagia Sophia and other Byzantine churches were transformed into mosques. The Greek patriarchate was retained, but moved to the Church of the Pammakaristos Virgin (Mosque of Fethiye), later to find a permanent home in the Fener (Phanar) quarter. The sultan built the Old Seraglio (Eski Saray), now destroyed, on the site occupied at present by the university, and a little later the Topkapı Palace (Seraglio), which is still in existence; he also built the Eyüp Mosque at the head of the Golden Horn and the Mosque of the Fatih on the site of the Basilica of the Holy Apostles. The capital of the Ottoman Empire was transferred to Constantinople from Adrianople (Edirne) in 1457.

After Mehmed II, Istanbul underwent a long period of peaceful growth, interrupted only by natural disasters—earthquakes, fires, and pestilences. The sultans and their ministers devoted themselves to the building of fountains, mosques, palaces, and charitable foundations so that the aspect of the city was soon completely transformed. The most brilliant period of Turkish construction coincides with the reign of the Ottoman ruler Süleyman the Magnificent (1520–66).

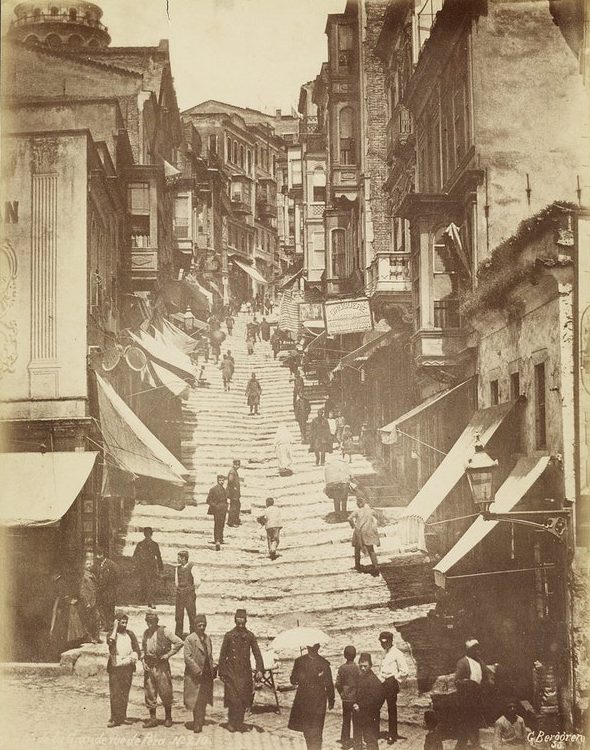

The next major change in the history of Istanbul occurred at the beginning of the 19th century, when dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire was approaching. This period is known as the era of internal reforms (Tanzimat). The reforms were accompanied by serious disturbances, such as the massacre of the Janissaries in the Hippodrome (1826). With the triumph of the progressive Ottoman sultan Mahmud II over the conservative opposition, the Westernization of Istanbul started apace. There was an ever-growing influx of European visitors who, since the 1830s, could reach Istanbul by steamship. The first bridge across the Golden Horn was built in 1838. In 1839 the Ottoman sultan Abdülmecid I issued a charter guaranteeing to all his subjects, whatever their religion, the security of their lives and fortunes. The process of Westernization was further accelerated by the Crimean War (1853–56) and the quartering of British and French troops in Istanbul. The latter part of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century were marked by the introduction of various public services: the European railroad extending to Istanbul was begun in the early 1870s. The underground tunnel joining Galata to Pera was completed in 1873; a regular water supply for Istanbul and the settlements on the European side of the Bosporus was brought from Lake Terkos on the Black Sea coast (29 miles [47 km] from the city) by the French company, La Compagnie des Eaux, after 1885; electric lighting was introduced in 1912 and electric street cars and telephones in 1913 and 1914. An adequate sewerage system had to wait until 1925 and later.”

Excerpted from: Encyclopaedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/place/Istanbul/Constantinople

Armenians in Constantinople

Since the time of Constantine I (the Great), i.e. since the fourth century, Armenians are said to have lived in Constantinople, which in Armenian, as in Greek, is still usually referred to simply as ‘Bolis’ (polis – the city). An Armenian parish has been documented since the year 572. Due to the strong immigration in the 19th century, the Armenian community grew considerably. In 1844, 160,000 Armenians were counted there, out of a total population of 891,000; in the second half of the 19th century, this figure had already risen to a quarter of a million.

The massacres of 1895 and 1896 and the subsequent flight of many Armenians abroad lowered their number to 163,670 before the First World War.

Armenians in Byzantine Constantinople

Armenian history of late antiquity and the Middle Ages was closely intertwined with Byzantine history. The Byzantinist Peter Charanis wrote: “Many Armenians came into the Byzantine empire even when Armenia was under foreign control. They came sometimes as adventurers, but more often as refugees. Thus in 571, following an unsuccessful revolt against the Persians, numerous Armenian noblemen, headed by Vardan Mamikonian and accompanied by the Armenian Catholicus and some bishops, fled to Constantinople. Vardan and his retinue entered the Byzantine army; the rest seem to have settled in Pergamon where an Armenian colony is known to have existed in the seventh century.”[3] And further:

“It was through the army that the Armenian element in the Byzantine empire exerted its greatest influence. It is well known that the Armenian element occupied a prominent place in the armies of Justinian. Armenian troops fought in Africa, in Italy and along the eastern front. They were also prominent in the palace guard.”[4]

Particularly in the ninth and tenth centuries, Armenians occupied leading positions in the political life of the Byzantine Empire and especially in its army, as emperors (especially in the Macedonian dynasty) and army commanders.

“In their relations with Armenian chieftains the Byzantines developed the practice of having them yield their possessions to the empire in return for lands located elsewhere in the empire and also for titles and offices. It was an effective way, at least in some instances, of extending the frontier eastward and at the same time integrating recalcitrant elements into the military and political life of the empire. The practice may already be noted under Basil I when, it will be recalled, the Armenian Kourtikios who turned Locana over to the empire, was given a place in the military organization of the empire. It may be noted under Leo VI when another Armenian chieftain, Manuel, ceded Tekis to the empire. Manuel, it will be recalled, moved to Constantinople where he was showered with honors while two of his sons were given new holdings in the region of Trebizond and the other two, important military commands. It was in this way too that the district of Taron had been definitely annexed to the empire in 966. The dispossessed princes were not always happy writh the new arrangement but they usually ended, as it has been pointed out above in connection with the Taronites, by integrating themselves into the military and political life of the empire.

This practice was applied on a large scale during the reign of Basil II and resulted in the annexation by the empire of virtually all Armenia. In most instances, the cessions were induced under pressure and not infrequently force was required to bring about actual annexation.”[5]

Peter Charanis concludes:

“For something like five hundred years, Armenians played an important role in the political, military and administrative life of the Byzantine empire. They served as soldiers and officers, as administrators and emperors. In the early part of this period during the seventh and eighth centuries, when the empire was fighting for its very existence, they contributed greatly in turning back its enemies. But particularly great was their role in the ninth and tenth centuries when as soldiers and officers, administrators and emperors they dominated the social, military and political life of the empire and were largely responsible for its greatness. So dominant indeed was their role during this period that one may refer to the Byzantine empire of these two centuries as Graeco- Armenian; ‘Graeco’, because as always, its civilization was Greek, ‘Armenian’, because the element which directed its destinies and provided the greater part of the forces for its defense was largely Armenian or of Armenian origin. It was a role, moreover, of world-wide historical significance for it was during this period that the empire achieved its greatest success, when its armies triumphed everywhere, its missionaries spread the gospel and with it, civilization among the southeastern Slavs, and its scholars resurrected Greek antiquity, thus making possible the preservation of its literature. Herein lies perhaps the most important part of the legacy of the Armenians to civilization. But while all this may be true, the point should be made and made with emphasis that the Armenians in Byzantium who furnished it with its leadership were thoroughly integrated into its political and military life, identified themselves with its interest and adopted the principal features of its culture. In brief, like many other elements of different racial origins, as, for instance, Saracens, Slavs and Turks, who had a similar experience, they became Byzantines.”[6]

Armenians in Ottoman Constantinople

The influence of Armenians continued under Ottoman rule. It was exacerbated by the distrust that the Ottoman conquerors of Constantinople felt toward the former Greek or Byzantine rulers. Greek Orthodox Christians were not allowed to live near the strategically important city walls after the conquest of Constantinople. However, Armenians were allowed to establish an Armenian Patriarchate in Constantinople, which at the same time benefited their control by the Ottoman rulers.

Among the influential families of the wealthy Amira class residing in Constantinople were the Duzians (Directors of the Imperial Mint), the Balyans (Chief Imperial Architects), and the Tatians (Western Armenian pronunciation: Dadians; Superintendent of the Gunpowder Mills and manager of industrial factories). The Tatians were originally from Akn (Trk.: Eğin; see also under kaza Eğin).

Notable Armenians, born in Constantinople

- Aram Antonian (Արամ Անտոնեան – West Armenian: Andonian; 1875 – 23 December 1951), journalist; genocide survivor

- Arpiar Arpiarian (Արփիար Արփիարեան; 21 December 1851 – 12 February 1908), writer

- Balyan (Balian) family, dynasty of architects

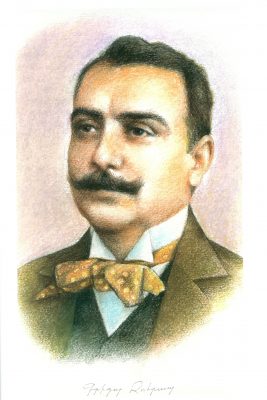

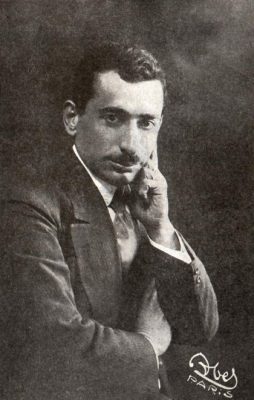

Grigor Zohrap / Zohrab (1861-1915; painter: Khoren Hakobyan) - Hagop Kazazian Pasha (also: Agop Kazazyan; 1836–1891), minister of Finance

- Bedros Durian (Պետրոս Դուրեան – West Armenian: Bedros Durian; 1851-1872), poet

- Yervand Otian (Երուանդ Օտեան or Երվանդ Օտյան; West Armenian: Yervant Odian; 19 September 1869 – 1926), writer, satirist

- Levon Shant (Լեւոն Շանթ; born Levon Nahashbedian, then changed to Levon Seghposian; 6 April 1869 – 29 November 1951), playwright, writer; genocide survivor

- Grigor Zohrap (Գրիգոր Զոհրապ – West Armenian: Krikor Zohrab; 26 June 1861 – 1915), statesman, author; genocide victim

Republican era (1923–present)

- Agop Dilâçar (Յակոբ Մարթաեան – Hakob Mart’aian, 22 May 1895 – Istanbul, 12 September 1979), linguist of the Turkish language and co-founder of the Turkish Language Association

- Shahan Shahnour (3 August 1903 – 20 August 1974, Saint-Raphael), French-Armenian poet and writer

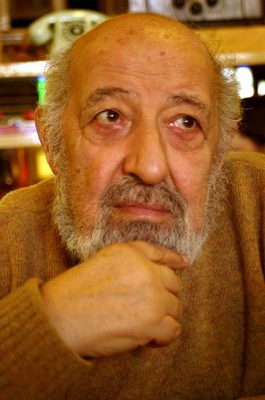

- Ara Güler (16 August 1928 – 17 October 2018), photographer

- Arman Manukyan (Արման Մանուկյան, 21 March 1931 – 28 December 2012), professor, writer, economist

- Şahan Arzruni (Շահան Արծրունի – Shahan Artsruni; born 8 June 1943), concert pianist

- Sevan Nişanyan (Սեւան Նշանեան – Sevan Nshanian, born 21 December 1956), writer

The Gate to Bliss – “a starving city…”: Constantinople in the First World War

“‘Constantinople is a starving city where certainly dozens of poor creatures die every day and where epidemics like typhoid, cholera and plague have never been absent for a year and a half. Constantinople is dirty and everywhere hangs the fearsome spirit of famine (…) One can see very poorly dressed Turkish soldiers aimlessly vagabonding through the streets in a deathly tired state.’

This is how a newspaper correspondence described the prevailing conditions in February 1917. They were caused by the poor supply of food to the population, but also by the pitiful state of health of the soldiers returning from the front. Every day one saw women suffering from malnutrition collapsing in the streets. Every day several dozen people died in the city from various infections. Many children became orphans and had to be housed. In total there were nine thousand children in fifty orphanages. It was striking that about half of them were Armenian children. The living conditions were miserable.

The Greek-language newspapers were full of obituaries of young people. My family was not spared from the epidemics. Grigorios’ job in a warehouse on the Golden Horn, near the port of Galata, where the sewage from the surrounding neighborhoods was piped, was already endangered for hygienic reasons. In addition, the sacks of flour and grain unloaded there were themselves a permanent and major source of danger, because they attracted mice and many of the rampant infections were transmitted through them. My grandfather also became infected in this way. He died after a short illness on March 30, 1917, at the age of forty-two, leaving behind a pregnant wife and two girls aged nine and seven. The son he longed for, my father, was not born until three months after his death on June 20, 1917. In memory of her late husband, Eleni named her son Grigorios as well.”

Excerpted and translated into English from: Asderis, Michael: Das Tor zur Glückseligkeit: Migration, Heimat, Vertreibung – die Geschichte einer Istanbuler Familie. Berlin: binooki, (2018), p. 129f.

Destruction

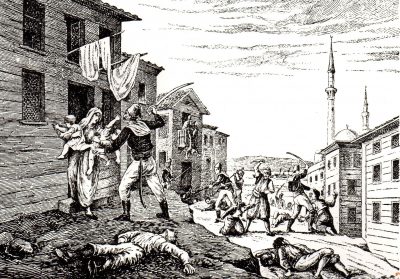

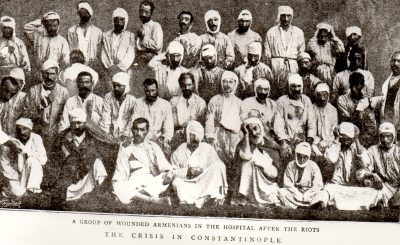

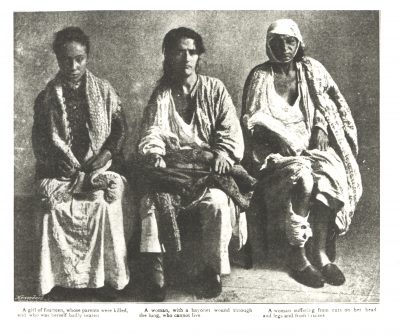

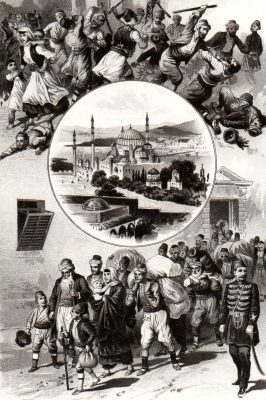

1895-1896: Repeated Massacres

The massacre of up to 16,000 Armenians in Sassun in August 1894 also provoked outrage in Europe and, along with the almost simultaneous Greek massacres in Crete (1895-96), earned Abdül Hamit II the moniker ‘bloody sultan’.

Once again there were calls for reform, but of the six “Powers,” Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy had lost interest in Western Armenia. It was only British involvement that led Britain, Russia and France to join forces once again in 1894 to push for the realization of the reform promises and to present their own reform project on 17 April 1895, after the Ottoman government had remained inactive.

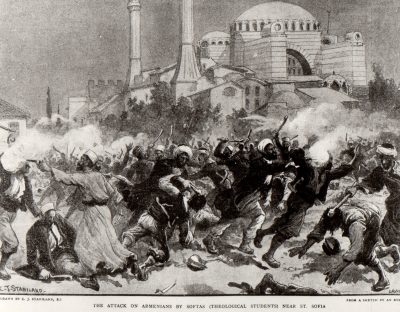

However, as month after month passed without the Ottoman government taking a position on the proposals, the Armenian Hnchak party organized a protest demonstration on 1 October 1895 to hand over a list of Armenian “protest demands” to the government. However, en route, the demonstration was stopped and banned by the police. About 20 of the mostly unarmed demonstrators were shot dead, and Islamic counter-demonstrators, who had been mobilized beforehand, pursued the fleeing Armenians and killed bystanders in remote neighborhoods. Three thousand panic-stricken Armenians took refuge in Armenian churches, where, without food, they were besieged by the police for days until the Russian Embassy intervened to mediate. The demonstration, which was presented as an “attempted uprising,” served as a pretext for launching massacres against the ermeni millet throughout the country, which had apparently been prepared for a long time.

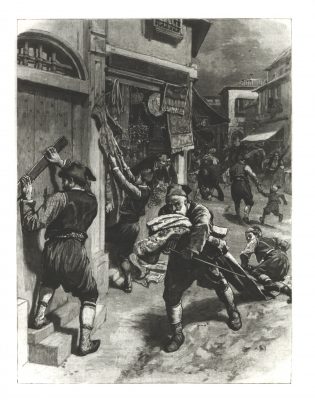

The massacres were repeated less than a year later, after 25 young Dashnaks took control of the Ottoman Bank in Constantinople on 26 August 1896 and threatened to blow themselves and the 160 employees up if their political demands were not met. However, they only achieved their free departure to France. Sultan Abdülhamit II, who had long been informed of this plan by his informers, calmly waited for the bank occupation. However, on the same day, a pogrom by the “Bashibuzuks” broke out in Constantinople, supported by Kurdish, Laz and Turkish gangs, who killed about 14,000 Armenians with clubs. Many of these religious fanatics were in fact police spies in disguise. Massacres also occurred again in the cities of Van, Akn (Turkish: Egin) and Niksar in June and September 1896. The Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople estimated the total number of victims at 300,000. Another 100,000 Armenians fled to the Russian Empire, the Balkans, and the United States, and at least as many were forcibly Islamized, reducing the number of Armenians in the Ottoman Sultanate by at least 400,000 in 1896. 568 churches and monasteries were plundered and destroyed, 2,500 villages were devastated, crops were destroyed or not harvested for lack of equipment, livestock and labor, and famine, cholera and plague broke out.

Eliticide

As in adjacent Thrace, mass arrests and deportations of the spiritual and clerical leadership among the Greek Orthodox minority began in the Ottoman capital Constantinople. The boycott policy against Christian Ottomans, especially against the Greek Orthodox population, which began with the Balkan Wars (1912/3), turned into mass arrests and deportations:

„In Constantinople itself boycotting and illegal arrests and imprisonment increased to an alarming extent.

Written orders were now given to the Greeks by the boycotters to evacuate their shops within a definite time limit. Thus, in the Top-kapou [Topkapı] quarter, the grocer Mavromati was ordered to evacuate his shop within three days, while the police to whom these facts were reported, refused to interfere, just as it had previously refused to act when in the same quarter of the city and under its very eyes, the bread of the baker Vlademir had been spoiled with kerosene oil. From the village of Arnaoutkioi [Trk.: Arnavutköy – ‘Albanian village’], in the district of Derkon and in the vicinity of the capital, Panayotis Nicolaou, Antonius Thomas, Constantinos Sawas, Michael Stavrou, Michael Constantinou, Demosthenes Anastasiou, Diogenes Panayotou, the twelve-year old Anastasios Michael, Nicolaos Demetriou, Antonius Drammata and Angelis Michael, a shepherd, were carried away and have disappeared. All these men were working in the pottery of the village and were deported by about forty armed Mussulmans from the neighboring village of Samlar.”[7]

In March 1915, 200 Greek Orthodox Christians were arrested and deported from Constantinople. The Hellenic Embassy in Constantinople, in its communication 1246 of 2 March 1915, mentioned as many as 10,000 Greeks deported from the capital city to Asia Minor:

“March 1915.

CONSTANTINOPLE

- Koulekli was murdered at Baloukli. The number of the Greeks from Constantinople who have been arrested and expelled to Asia Minor amounts to 200. Among them are the following persons: C. Theodorou, G. Vassiliou, Th. Vassiliou, G. Demosthenes, V. Athanassiou, Th. Karaniitsos, T. Vassiliou, Ch. Stylianos, P. Symeon, C. loannou, G. Panaghiotou, L. Nikolaou, A. Karakos, P. Vitalis, M. Apostolou, V. Joseph, E. Anastasiadis, A. Deskosmidis, L. Gcorgiou, N. Zographidis, E. Manouelidis, I. Papoulis, P. Constantinou, P. Samamas, N. Athanassiou, N. Demon, Ch. Vassiliou, Tli. Prodromou, N. Demetriou, V. Saphaidaris, S. Okoumoush, D. Saphir, Th. Demetriou, S. Gregoriou, G. Photiou, D. Roumounos and Z. Ignatiou. It should be noted that according to the communication No. 1246 of March 2 [1915] of the Legation of Constantinople (Ministerial Archives, No. 2866), the total number of the Greeks deported to the interior of Asia Minor is 10,000.”[8]

In June and July 1915, the arrests of Greek Orthodox Christians continued. In the sancaks and kazas of Büyükdere, Çorlu (Tyroloi), Çatalca and Silivri, 60 more Greeks were arrested and imprisoned in Constantinople, and after a few months they were also deported, including „Archmandrite A. Papadopoulos, the Archivist of the [Ecumenical] Patriarchate (…) [and] [t]he abbot of the Monastery of St. George at Prinkipo, the priests loannis Oekonomou and Cyrillos, of Bouyoukdere [Büyükdere], as well as the Archmandrite Gennadios (…).”[9]

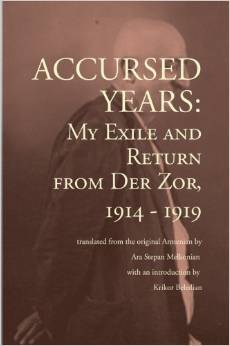

In March 1915, preparations also began for the extermination of the Armenian elite. Armenian journalist, author, and genocide survivor Yervand Otian mentioned in his memoir Accursed Years that the Constantinople police were compiling lists of Armenians for deportation as early as March 1915:

„At that time a rumor went around, to which we didn’t give much credence. According to this story, the police were preparing lists for the deportations of many Armenians:

‘A list of 6,000 Armenians has been prepared’, said one.

‘No, apparently the list is only of 2,000 Armenians’, assured another. For days we heard about this list, as I said, without believing it. But all these stories gradually began to worry us. There was a threat in the air.”[10]

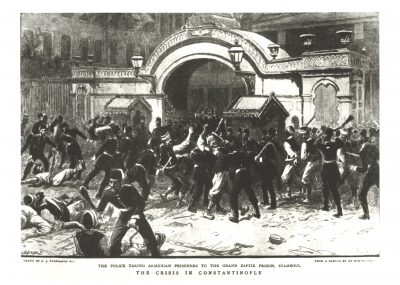

On ‘Red Sunday’, 24 April 1915, a number of prominent Armenians were indeed arrested in the Ottoman capital and deported to the interior of the country on alleged suspicion of treason, for alleged further investigation. The place of exile for political activists was Ayaş in Ankara province, and for the remainder Çankırı in Kastamonu province. Data on the number of people arrested varies by a factor of ten, from 235 to 2,345. Turkish scholar and genocide researcher Taner Akçam mentions an official statement of 24 May 1915, according to which 2,345 people[11] had been arrested by that date in connection with ‘Red Sunday’. The arrests served a multi-faceted purpose: they were intended to discriminate against Armenians of Ottoman nationality as potential traitors to the country and thus as an imminent threat to state security, and hence ‘justified’ the subsequent measures against the Armenian population: forced labor, death marches and massacres.

Among the Armenians arrested on ‘Red Sunday’ were writers, poets, publicists, journalists, teachers, doctors, pharmacists, merchants, those active in political offices or associations, and members of the clergy.

“The summonses to the precinct always followed the same pattern. Everything was very tactful and silent. On the part of the police, strict care was taken to avoid any resistance, incidents or even public disturbances. It usually began with someone ringing the doorbell of a person on the list. When the door was opened, the visitor introduced himself as an officer of the local police station. He was in civilian clothes, very courteous, and he spoke politely, apologizing for what was sure to be an unpleasant disturbance. Then he asked if the householder could come to the nearest police station for clarification of a simple, minor matter. Often it was a matter of translations of documents from French or Italian. For the police officers, ignorant of these languages, the small effort would be very valuable. This way, they could quickly investigate a suspicion of fraud, the officer said. It would not take long, maybe ten to twenty minutes. Most of the people who were looked up agreed immediately and went to the station unsuspectingly. Some even went in their pyjamas, assuming they would be right back. If they were not present, they were asked to report after their return. Of course, everyone complied, because no one suspected anything bad.

When they arrived at the police stations, the summoned persons were forbidden to communicate with each other. After their pockets were searched and their identity papers confiscated, they were loaded into red fire trucks. Then a police officer took a seat between each of them. It was obvious that he was to watch out so that during the ride no one would make himself noticed by shouting loudly and thus inform or warn the passers-by. Everything was well organized. All rides ended at the large central prison of Constantinople. There, to their great surprise, the arrestees found that it had recently been completely emptied. Not a pickpocket, burglar or murderer was to be seen. A huge prison and its guards were waiting for the inmates. For people who had never been imprisoned before. They came one by one, throughout the night.

Immediately upon arrival, the groups were led into a large hall where an official present read names from two lists he had in front of him, so that as soon as a person’s presence was confirmed, he could check off that particular name. Now it was clear that they were systematically arrested, but none of them was aware of any guilt. (…)

After some time of waiting, the prison director, Ibrahim Effendi, appeared and said to the officer present in a conspicuously polite tone:

‘Take the gentlemen to the guest houses!’

Thereupon, the official said in a stilted and smiling manner:

‘May I ask you to follow me?’

The exaggerated politeness of the official, the empty cells and the refusal to give any information about what they were accused of seemed unreal. Uncertainty spread.

It was not until the director of the Pangaltı Department of the dreaded National Defense Council was brought in during the night that they understood that their vague hunch, which they did not want to believe, was to be proved right. They were not accused of any crimes, because the last person to be brought in was a high-profile supporter of the ruling Unity and Progress Committee. He was certainly not guilty of anything. But he was Armenian, like all of them. Now it was clear to everyone what they had been arrested for.

(…) Very few survived.”

Excerpted and translated into English from: Asderis, Michael: Das Tor zur Glückseligkeit: Migration, Heimat, Vertreibung – die Geschichte einer Istanbuler Familie. Berlin: binoki, (2018), pp. 119-121

GREEK-ORTHODOX ARCHBISHOPRIC OF CONSTANTINOPLE

“During the period of the deportation of the Greek element, and when it reached its height, the emigration also of the inhabitants of Thrace was rapidly followed by that of the coast of Asia Minor. A strict boycott was started in the Capital itself having as its sole object in view the expulsion of the Christian element, so as to present Constantinople in the light of an exclusively Moslem city.

Systematically organized, cleverly applied and supported as it was by all the oppressive measures devised by the Young Turk’s program, this boycott would doubtless have resulted in a great catastrophe for the Greek element had the European War not broken out at a very critical moment, and diverted the immediate and serious attention of the Government elsewhere. At that time it was a question of enforcing a premeditated plan for the wholesale deportation and extermination of the Christian element in the provinces, so as to facilitate the execution of their designs with reference to Constantinople.

The boycott had, nevertheless, the effect of bringing trade to a standstill, especially in the quarters of Potira, Xyloporta, Sarmatchik Top-capou [Topkapı], Tekfour-Serai [Tekfür-Seray], Kashim Pasha [Kaşım Paşa], Vlanga, Alti-Murmur [Altı-Murmur], Psamatia, Yedikoulle [Yedikule], Sirkedji [Sirkeci], Bechiktache, and Ortakeuy [Ortaköy].

The only place in which deportation on a grand scale took place was in the community of Stenia. The population of this parish numbering 320 inhabitants, were dispersed by order of the Chief of Police of Arnaoutkeuy [Arnavutköy], in July, 1915. They all took shelter in the suburbs of the Capital, with the exception of five families whose heads were in the Government employ of the locality.

Isolated cases of expulsions were however numerous, some being sent to Brouse [Bursa, Grk.: Proussa] and the interior of Asia Minor, simply because it was suspected they were opposed to the orders or decision of the Government.”[12]

Deportation

In view of the presence of numerous foreigners in the Ottoman capital, including many embassy staff, the Young Turk regime refrained from the complete deportation of all Armenian or Greek inhabitants. However, in Constantinople ‘non-residential’ Armenians who had come into the city from elsewhere were mostly deported inland. According to the President of Police in the Ottoman capital in summer 1915 alone 30,000 Armenians were shipped out of the city and another 4,000 followed early that winter. About 30,000 Armenians had already fled Constantinople in the summer of 1915.[13] The German theologian, missionary and documentarist of the destruction of the Ottoman Armenians, Johannes Lepsius, reporting to the German Chancellor (head of government) on 29 November 1915, gave the figure of 10,000 Armenians who were deported from Constantinople and most of whom were probably murdered in the Izmit mountains.[14]