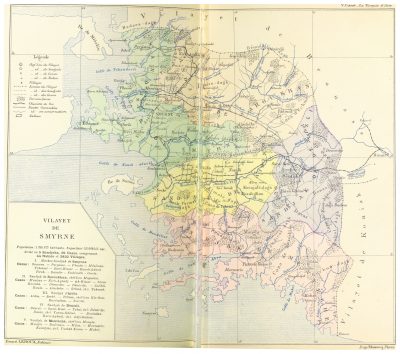

Located in the south-west of Asia Minor, the province of Aydın comprised the ancient regions of Lydia, Ionia, Caria and western Lycia. The Encyclopædia Britannica described it by 1911 as the “richest and most productive province of Asiatic Turkey”. [1]

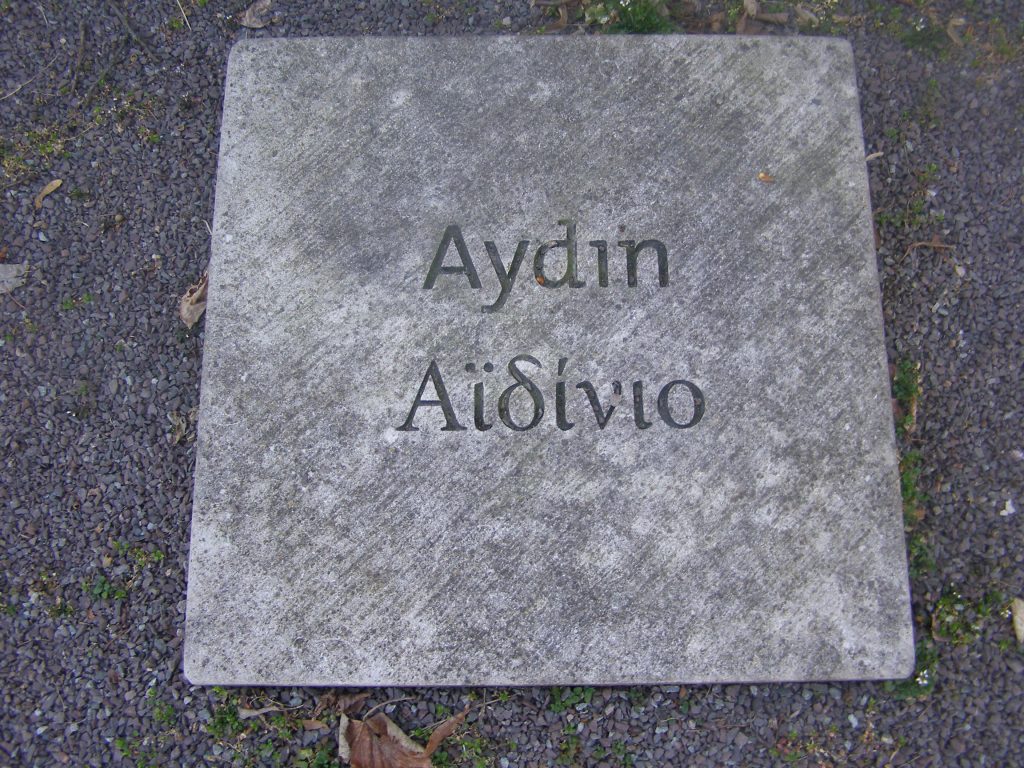

Toponym

The name of the province comes from the principality of the Aydınoğulları, who ruled the region before the Ottomans (in Greek: Αϊδίνιο – Aidinio). The province was also known as Smyrna or Smyrni province after its capital of the same name.

Administration

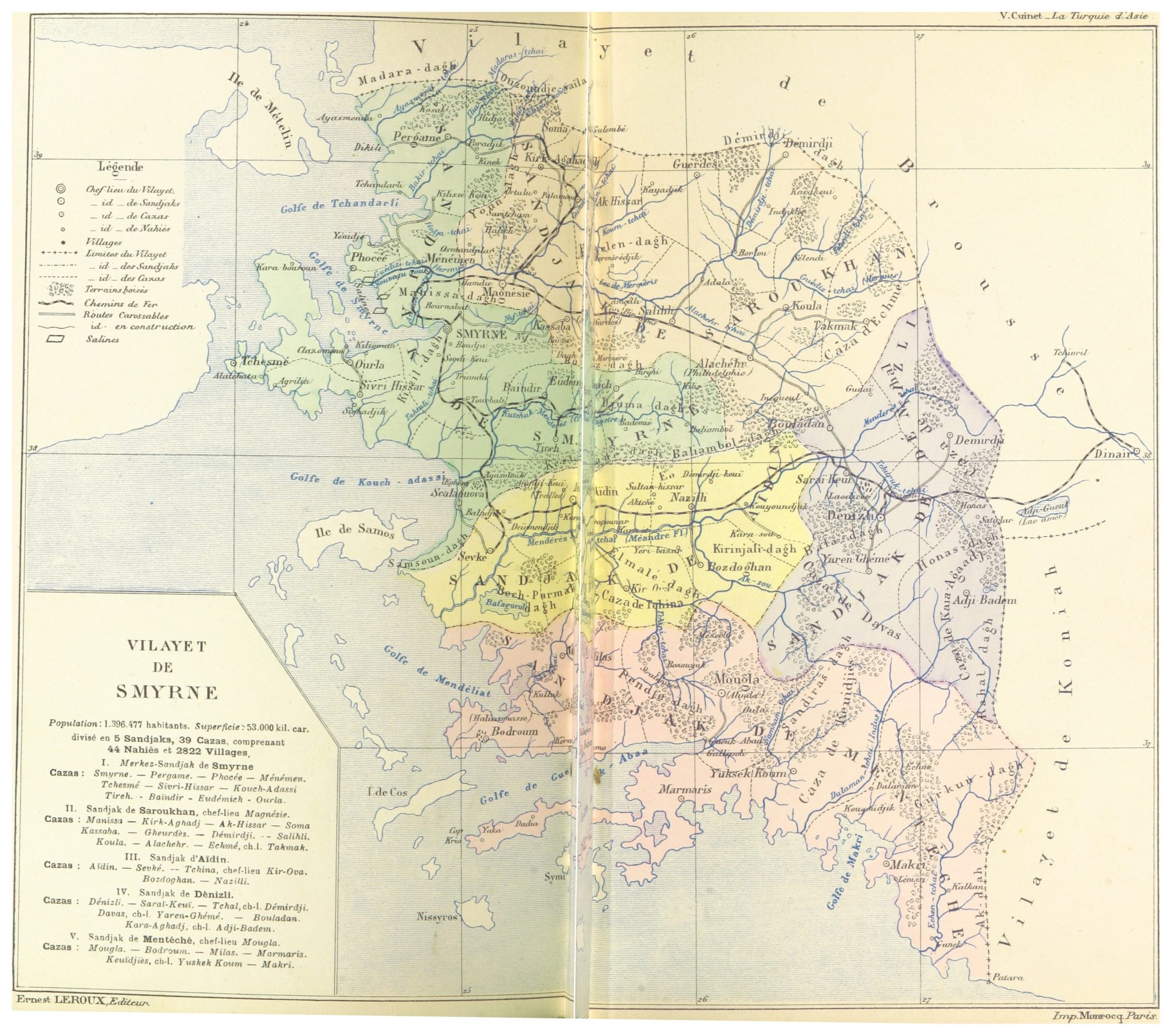

The Vilâyet Aydın, established in 1864, originally included only the three sancaks of Smyrna/İzmir, Aydın and Muğla (Grk.: Mobolla; Menteşe). Following an administrative agreement, the newly created sancak Manisa (Saruhan) was added in 1877. In 1892, the number of sancaks increased to five with Denizli, comprising 39 kazas (1893). The Smyrna (Trk.: Izmir) sancak was the center of the province. By the 1900s, the vilâyet encompassed most of what is now the Aegean region.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Aydın Vilayet reportedly comprised an area of 45,000 km2.

Population

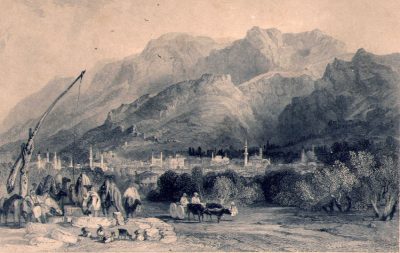

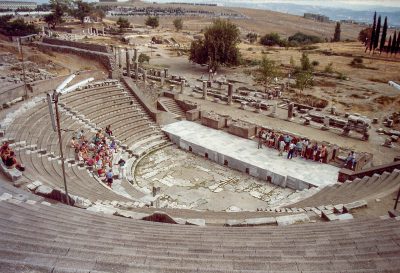

The Aegean coast of Asia Minor once had been home to the Ionian Greeks who counted among their citizens the philosophers Thales, Pythagoras, and Anaximander.(2)

The preliminary results of the first Ottoman census of 1885 (published in 1908) gave the overall population as 1,390,783.

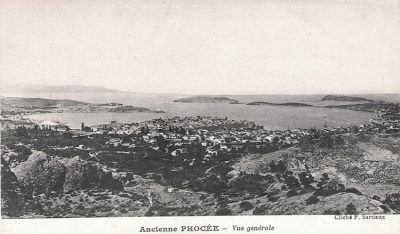

According to the Ottoman census of 1893, in 35 of the total of 39 kazas Muslims were the majority. In the kaza of Smyrna/Izmir there was no majority but Muslims were the largest group. In the three kazas of Foça, Urla and Çesme, comprising the Karaburun Peninsula, Greeks were the majority. However, according to American pre-Greco-Turkish War (1919-1922) estimates, the Greek element was the most numerous in Smyrna Sancak with 375,000 inhabitants, while other groups included Muslims (325,000), Jews (40,000, predominantly Sephardic and Romaniote/Grekophone) and Armenians (18,000).[3]

The census of the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople gave the Armenian pre-war population in the province of Aydın with 21,145. The Armenians lived in 16 localities of the province – but more than the half of them, 11,000, in the city of Smyrna(4) – and maintained 26 churches, one monastery, and 27 schools with an enrolment of 2,935 pupils.[5]

Economy

The British described Aydın Vilayet as having a “remarkable variety of agriculture”, as of 1920. The province produced grains and cotton, specifically in Aydın and Nazilli. The region also produced opium, tobacco, and valonia oak. Fruit was one of the most popular exports, with figs and grapes being especially popular. Before World War I, fig production was up, with an expansive increase in production and exportation via railway. Grapes were used to produce raisins, and licorice was also produced in the region. It was noted as growing wild along the Büyük Menderes River (Grk.: Μαίανδρος – Maíandros; Meander). It was exported to the United States and United Kingdom.

Aydın, as of 1920, was considered to be the world’s supply center for emery, specifically in the areas between Tire and Söke. In the early 20th century, Aydın was also noted for large deposits of chromium, specifically near Mount Olympus and in the southwestern region of the vilayet. Antimony and mercury were also found in the area.

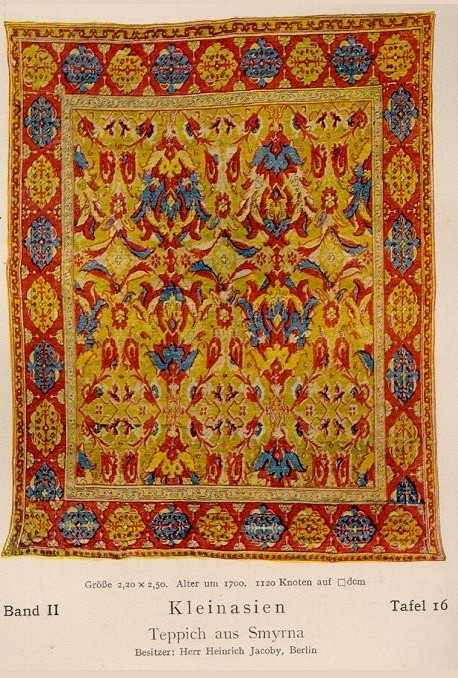

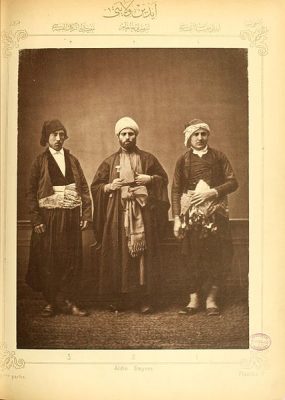

Carpet was manufactured in the Vilayet, mainly in Smyrna, but with carpet being made throughout the region, including in Kula, Uşak, Gördes and Isparta. After World War I, sales declined. However, Britain remained a major importer of carpets from Aydın. Carpets were mainly produced by women. The Encyclopaedia Britannica defines Smyrna carpets as “any large, coarse carpet handwoven in western Anatolia and exported by way of İzmir (Smyrna). It is likely that Smyrna carpets originally represented the production of the town of Uşak, to which was added in the late 19th and early 20th centuries the large carpets newly developed at such centres as Ghiordes, Kula, and Demirci.

The name Smyrna has been applied more specifically to a pattern, usually seen in small examples, that represents a degenerate form of a floral pattern used in the Ottoman court production of the 16th and 17th centuries. Since these 18th- or 19th-century Smyrna carpets are rare, it is probable that more imitations than originals exist.”[6]

As of 1920, the region was noted as having 6,000 square kilometers of forest. The west and southwest had the most thickly forested areas. The British described Makri as being “rich in excellent timber.” Cedars were found in Makri, with oak and pine throughout the vilayet. In the early 20th century, deforestation had begun via private companies of the vilayet. Sawmills had been erected, with Makri having its own steam-run sawmill. Most trees were felled by hand at this time. Tavas also had a timber economy during this period.

Destruction

Unlike almost all other Ottoman provinces, in Aydın province the Greek Orthodox Christians and not the Armenians were the main victims of forced labor, massacres and deportations before and during the First World War. In terms of the time span of the persecutions of Greeks, the province can only be compared to that of Adrianople/Edirne. In both provinces, massacres and deportations of the long-established Greeks started during the Balkan Wars. These peculiarities of the wealthiest Ottoman province have something to do with the person of the provincial governor Mustafa Rahmi Arslan Bey (1874-1947).

The Second Dragoman (interpreter) of the German Consulate of Saloniki, Dr. Heribert Otto Paul Schwörbel (1881-1969), described Rahmi, who ruled his realm like an autocrat as the initiator of anti-Greek activities in 1914. GustavHumbert, 1910-1915 the German consul to Smyrna, expressed a similar view; on 14 March 1915 he wrote to the German Embassy in Pera (Constantinople): “As much as he [Rahmi] hates the Greek element, he flirts with the affluent English and French.”[7]

Giles Milton, following the positive description of Rahmi by the US-consul to Smyrna, George Horton (1859-1942), describes Rahmi as a high ranking and influential C.U.P. member of Jewish ancestry from Saloniki, “benevolently devious” and in particular a friend of Smyrna’s Levantine elite, but hostile to the Greek Orthodox Christians.[8]

Before the First World War

Already before the war Grand Vizir Said Halim, the Ottoman head of government in 1913-1917, informed the German Ambassador about the “total removal of the Greek population from the littoral of Asia Minor.”[9] On 5 March 1915 Said Halim proudly announced that “the littoral of Asia Minor has more or less lost its Greek population”.[10]

The Second Dragoman of the German Embassy to Constantinople, Dr. Schwörbel, travelled twice in official missions to Ionia during summer 1915. He reported also the presence of concentration camps[11] along the Soma-Bandırma railways with Greek women, children and old peoples; they were deportees from the Marmara coast, entirely left to themselves without food and accommodation: “Because the government does not care at all about feeding these masses and because under the recent conditions the possibilities for the deportees to find work or to earn any money are scarce, the daily casualties are high, as the railway physician of the Soma-Pandarma line confirmed.” Schwörbel concluded:

„With the exception of Aivali and Smyrna with its environs the entire Greek civilization, which flourished until recently at the west coast of Asia Minor is destroyed. The reason lies in the Islamist movement in Asia Minor, initiated in the beginning of May last year [1914] by the recently immigrated refugees from Macedonia and Mytilene and stirred up by the general governor of Smyrna, Rahmi Bey, with the aim to expel the Christian populations from Asia Minor and to replace them with Muslims.“[12]

An earlier German eyewitness in Ionia, Dr. Harry Stürmer, worked in Constantinople as foreign correspondent for the Kölnische Zeitung (Cologne). In his memoirs, published in 1917 in neutral Switzerland, he recalled the situation at the beginning of WW1 in 1914: „At the time of the Sarayevo murder I happened to be in the Aydin vilayet, in Smyrna and its hinterland. There I have witnessed with my own eyes vile deeds which must make everybody blush in anger against the Turkish government, which tolerates and supports these crimes, starting with old women, raped one after the other by a dozen of muhacirs and wayward soldiers, up to the smouldering ruins of Phokaia.“[13]

A report of 19 June 1914 (full text see below) about ‘disorders in the Vilayet of Aydin[14]’ by the Danish consulate at Smyrna to Denmark’s Legation at Constantinople describes in detail the mechanism of terrorizing and expelling the Greek inhabitants who had been compelled to accommodate in their own homes Muslim refugees from Thrace and Macedonia, providing one room out of every three. At a later stage, armed Muslim bands openly attacked Greek settlements and towns: “(…) women were seduced, girls were ravished, some of them dying from the ill-treatment received, children at the breast were shot or cut down with their mothers.”[15]

Alfred Van der Zee to Carl Ellis Wandel: Report of 19 June 1914

On 19 June 1914, the Danish consul at Smyrna, Alfred Van der Zee, reported to the Danish diplomatic minister Carl Ellis Wandel (Constantinople):

“About three months ago the Governor General of Smyrna, acting as I understand on instructions from the Ministry made an inspection in the small towns situated at the coast of this province. It would appear that in the course of this tournée administrative he gave semi-official orders to the sub governors to force the Greek population resident therein to evacuate these towns. No order of expulsion was decreed but the Turkish officials were to make use of the tortuous and vexatious measures so well-known to them. –

The like instructions were, I understand, given by the Governors of the other maritime provinces. The reason for this measure was, from what I gather, the belief that so long as the Greeks were in possession of Chios & Mitylene [Lesvos], the presence of a kindred population on the opposite littoral constituted a source of danger to the Empire. As a result of these instructions a severe boycott was shortly after proclaimed and measures, many and different, were adopted to compel this population out to quit their hearths and homes. –

As the rayah Greeks clung however to their fields it was decided to take more active steps. The immigration of Thracian & Macedonian refugees gave the local authorities the opportunity for more harassing measures. –

A proclamation was issued that in order to house the mohadjirs [muhacirler], one room out of every three in the dwellings belonging to the rayah Greeks was to be given to them: further the local authorities were to see to the execution of this order.

The results are easily comprehensible. Unable to live with their guests, the Greek rayah began to emigrate, selling their property for what they could get for it and seeking new lands for their exertions, but the process was naturally a slow one as in a land where the peasant has little money it was naturally difficult to realise property from one day to another. –

The local authorities then determined to activate matters and more imperious orders were sent from head-quarters. –

As a direct consequence of these orders trouble broke out at Adramyt, on the coast just opposite the northern part of Mitylene.-

After open hints that it would be advisable for them to leave the place, menaces that they would be done to death were resorted to, and finally the threats began to take shape in the murder of villagers returning from their fields and the waylaying of townsmen. A reign of terror was instituted and the panic stricken Greeks fled as fast as they could to the neighbouring island of Mitylene. –

Soon the movement spread to Kemer, Kiliseköy, Kinick, Pergamos and Soma. Armed bands of Bashibozuks attacked the people residing therein, lifted their cattle, drove them from their farms and took forcible possession thereof. –

The details of what took place harrowing, women were seduced, girls were ravished, some of them dying from the ill-treatment received, children at the breast were shot or cut down with their mothers. –

Not content with driving the rayahs out, these blood-thirsty emissaries of a ‘so called Constitutional Government’ then attacked the property of foreigners driving out their employees, lifting their cattle and looting their farms. In answer to complaints made to the authorities the reply was: ‘Let foreigners go and buy farms in their own lands!’ –

From Pergamos the bands advanced to Dikilli driving out the people and looting the town, then, dividing forces, some bands took the direction of Menemen and others went south towards Phocea [Phokaia; Trk.: Foça]. –

In the Menemen district the villages of Ali-Agha and Gerenköy were partly sacked after having been looted, the affrighted inhabitants fleeing in all directions. –

At Serenköy, a village in the same district, the people determined to resist and a fierce fight took place lasting from 8 ½ at night till about one o’clock in the morning, when the villagers’ ammunition having failed, a hand to hand struggle was sternly fought in which most of the defenders, who were by far the minority, fell, after having heroically fought for their lives and for the honour of their women. –

The few survivors who escaped sought refuge in Menemen which the bands then threatened, but as this town is one of some 20,000 inhabitants they dared not openly attack it, but satisfied themselves with shooting the inhabitants who strayed out of its near neighbourhood.

The inhabitants thereupon decided to leave it but before doing so & perhaps hoping against hope, they determined to send away their wives and daughters.

On the 18th (…) some 700 women and about 300 to 400 children came to the railway station with the intention of taking train for Smyrna but by orders of Government no tickets would be given them & and the train passed without stopping. (…)

A few miles further down at the village of Ouloujak [Ulucak] the bashibozouks drove away all the cattle belonging to Greeks and ordered inhabitants, on threat of death, to leave the place. The unfortunate villagers were only too ready to comply with these arbitrary orders, but once again, by order of the Vali, the stationmaster was forbidden to deliver tickets & trains passed without stopping.

Afraid to return they lay huddled for two days and nights in the neighbourhood of the station, vainly calling to the passengers in the through trains to get assistance sent them. (…)”

Source: Danish consul Alfred Van der Zee til [to] Carl Ellis Wandel, 19/6 1914. Rigsarkivet [the Danish National Archives], Udenrigsministeriets Arkiver [the Archives of the foreign Ministry] (UM), 2-0355, ”Konstantinopel/Istanbul, diplomatisk repræsentation”, ”Noter og indberetninger om den politiske udvikling, 1914-1922”, ”Verdenskrigen. Rapporter fra Smyrna. Nov. 1914-marts 1916”].

During the First World War

Greek-Orthodox Victims

The extermination and expulsion of the Greek population occurred even before the outbreak of World War I through intimidation, massacres, deportations, and the settlement of Muslim refugees (muhaciler). On 24 July 1915, the retired French consul M. Guys reported from Constantinople on the fate of Greek forced laborers from the Smyrna area as well as Christian displaced persons throughout Anatolia:

“(…) In fact, all the Christian rayas, who had to do military service and were incorporated into the Ottoman army, shortly after the proclamation of the constitution in Turkey, were first set aside and disarmed, nearly five months ago, to form battalions of workers, condemned to forced labor, such as: the construction of roads and pavements, the digging of railroads, the sweeping of streets or the breaking of stones. Even today, I meet these convicts everywhere, whose clothing is strange, because some are dressed as soldiers, others wear the costume of their countries (these are the most numerous) and most of them, dressed in clothes and without shoes, having to be satisfied with a meager ration of bread which is distributed to them daily, which means that they are obliged to run after travelers to ask them for alms. I met several of them on my way between Tarsus and Bozanti, all Greeks, from the vicinity of Smyrna, Vourla [Trk.: Urla] and Tchesmé [Çesme], to whom I was in these parts, they had received only their ration of bread, the military authorities having served notice not to give them any clothes, shoes or headgear.

Secondly, the relentless persecution against the Christian rayas began in all the provinces of Anatolia, so that thousands of Greek raya families scattered all along the coasts of the Aegean Sea, were expelled and obliged to take refuge, at the time of the war in the Balkans, to the islands of the Cyclades like Chio, Metchin, Samos, etc, others living in the interior are, since almost six months, dispersed on all sides and chased to such a point that some, to find their salvation, were forced to convert to Islamism. This is what happened to the Armenian element, as the future will prove.”[16]

The insecurity of the Greek population in the province of Aydın was contributed to by the gangs of irregulars formed already before the outbreak of the war, which were as well responsible for the murder of numerous Greeks:

“(…) gangs of Turks were going about the open country, whose principal business was to prevent the Greeks, by force, from leaving the cities and villages in order to cultivate their lands, so that, being exhausted from hunger and terrorized they might of their own accord leave the country and their homes. These gangs were led by officers of the gendarmes, and were composed of prisoners undergoing a long sentence, who were released from jail in order to carry out this work, and, generally, of persons of bad character. About the doings of these gangs, which during the persecutions of 1913-1914 made their appearance as irregular bands without any organization whatever, a report from Adrianople, dated March 30, 1915, No. 19 (Ministerial Archives, No. 7278), treats but details as to these matters were made known by a report from Smyrna, dated January 10, and another dated March 30, 1915, under No. 72 (Ministerial Archives, No. 7278) which shows their entire organization. Thus, for the Province of Aidin, the center of the organization of the gangs was Magnesia [Manisa] , where it was decided that a gang of fifteen members should have its headquarters in the district of Salihi, of ten in that of Demirji [Demirci], of fifteen in that of Koula and of an equal number in that of Philadelphia (Alashehir) [Alaşehir].

The first activity of these gangs was noticed in the district of Ghiordes, where, after having attained their end, which was to prevent the Greeks from leaving their homes for the open country, the gangs entered right into the town and plundered the shop of Hadji Emmanuel Athanasoglou. The work assigned to the gangs of Demirji and Salih was to act against the Christians who were engaged in business in Mussulman villages. These through taxation, threats, beatings and plunderings of their shops were compelled to close up. The activity of these gangs was extended to such a point that under the cloak of the military uniform, they harassed the very environs of Smyrna itself where before the very gates of the city, within a period of two months, five attacks were made on Christians who were living on their farms.

The guilty co-operation of the authorities with these gangs is proved by the fact that when the chief brigand Hadji Moustafa imposed a tax of five thousand Turkish pounds on the village of Moursouli [Mursuli] of the Province of Aidin and the villagers denounced this act to the Moudir [müdür; high ranking Ottoman official] of Demirdji to whom they even gave the letter in which the demand had been made, the Moudir had some of the Christians arrested and imprisoned, accusing them of having actually forged the letter.” [17]

Armenian Victims

In contrast, the Armenian population of the Aydın province, which was small at around 21,000-30,000, was largely spared massacres and deportations before and during the World War. Raymond Kévorkian sees the reason for this not in vali Mustafa Rahmi alone, but primarily in the fact that the C.U.P. leadership focused on the Greek element during ethnic homogenization in this province. Giles Milton likewise underscores this specific of the Aydın situation:

„Smyrna alone remained untouched by Talaat’s policy. He did not dare – yet – to meddle with Rahmi Bey’s fiefdom, although [U.S. consul] George Horton feared that it would only be a matter of time before the deportation would be extended to Smyrna’s prosperous Armenian community. [18]

The German theologian Johannes Lepsius likewise referred to a termporary disparate treatment of Greeks and Armenians in ‘Western Anatolia’ in his documentary The Death Course of the Armenian People (1916) and attributed this to the provincial governor Mustafa Rahmi:

“In Western Anatolia there was never anything resembling an ‘Armenian question’. (…) If one wanted to have an ‘Armenian question’ in Western Anatolia, it had to be first created artificially by the government. The way of proceeding, however, made it unnecessary to look for any reason for the deportation of the Armenians from Western Anatolia. Two years ago [1914], the Greek villages on the western Anatolian coast and in the environs of Smyrna had already been cleared out without any reason and the inhabitants expelled from the country. Now they wanted to get rid of the Armenian population as well. Here, too, the Turkish population objected on various occasions to the deportation of the Armenians. (…) Nevertheless, the order of deportation was given to the Vali. The Vali Rahmi Bey refused to carry out the order; therefore, he had to come to Constantinople and justify himself. (…) Finally, the Vali Rahmi Bey was forced by the order of the Constantinople government to give the order of deportation, although a year later than the general deportation. Only the intervention of the Commander-in-Chief, General Liman of Sanders, who threatened military resistance, prevented the deportation of the Armenians of Smyrna from being carried out.” [19]

However, Armenians of the Aydın province were not completely spared arbitrary arrests and deportations during World War I, as Raymond Kévorkian evidences:

„(…) the Armenians of the vilayet of Aydın (…) were subjected to regular harassment until fall 1918. It should be recalled in this connection that all unmarried men from other regions living in Smyrna were gradually arrested and deported to the Syrian deserts. (…) on 1 November 1915, the city’s main Armenian neighborhood, Haynots (…) was surrounded by the army, which proceeded to carry out a systematic search and to arrest some 2,000 people. (…) several hundred people [were] sent in different directions on 28 November [1915] and then again on 16 and 24 December. Among them were a considerable number of British, Italian, and Russian subjects, many of whom died on the road. This suggests that Rahmi had profited from the occasion to eliminate these ‘foreigners’ and lay hands on their property, distributing part of it to police officials and members of the Itthadist club, such as Ali Fikri or Mahmud Bey.

(…) The Armenian Catholics, who had previously been spared because they were relatively well protected by the Austro-Hungarian consul, came under attack in September 1916. The police searched the Catholic cemetery on 16 and 17 September and claimed to have found bombs there. There is reason to think that this was a provocation engineered by the vali and the Unionists of the port city, for this ‘discovery’ provided justification for the arrest of 300 Armenian Catholics from Symrna, Cordelio, and Karataş, some of whom were deported to Afionkarahisar, were they were followed on 9 and 10 November by 300 to 400 people from the affluent classes. The choice of the people to be deported seems to have depended on the assets they possessed, coveted by this or that local or governmental official.”[20]

After the First World War: June 1920 – September 1922

In Ionia, massacres, committed by Kemalist forces and local bands had begun on 22 June 1920. These were described in a telegram of 11 August 1920, sent to the French Prime Minister by a committee of residents from towns of the Aydın province, i. e. from Nazilli, Sarayköy, Denizli and Khonesi[21]:

“(…) Kemal’s forces operating in the ‘Nazli’ region in conjunction with criminals who came from ‘Sokia’ [Söke[22]] and from Peran of ‘Meandros’, belonging to Sokiali Ali sub-command on the pretext of the advance of Greek army looted Christian houses at ‘Nazli’ [Nazilli] carrying off spoils. They burnt the city with explosive shells excluding Muslim neighbourhood and ended their mission with massacres and tortures against Christian population. Eye witnesses tell the story with terror that under smouldering ruins were found many charred innocent beings. According to calculations the number of the savagely massacred and dead under the ruins of ‘Nazli’ exceeds 500 persons.

The rest, more than 3,000 of whom were women, children completely stripped were driven by force to the interior in a deplorable condition, while the Turkish population with loot were transported by train.

Weak old people unable to follow caravan were savagely killed en route. Their corpses remain unburied.

On the road between ‘Eazei Kouyoudjak’ only, a distance of 12 kilometres, 53 corpses found. It is estimated that others, who were massacred were thrown in the Meandros [Trk.: Menderes] River.

The fate of those, who survived is unknown. According to information some survivors dispersed in various inhabited areas of interior in lamentable condition.

Fate of residents of ‘Saraköy’ [Sarayköy] totally unknown. Town looted, remains uninhabited. ‘Denizli’ where 20,000 Greeks were concentrated suffered the same fate.

Male population indiscriminately led to deserted island of Lake ‘Egridir’ [Eğridir][23]. Turks applied themselves to looting and orgies against women and children. Leaders of Kemal’s followers fight for distribution of spoils. Scared population abandons town. Fate of ‘Khonesi’ residents remains unknown“.[24]