Administration

Adrianople was a sancak center and was bound to, successively, the Rumeli Eyalet (Eyalet Rumelia)and Silistre Eyalet before becoming a provincial capital of the Eyalet of Edirne at the beginning of the 19th century. At times Edirne was also the residence of the governor of the Rumeli Eyalet.

City of Adrianople / Αδριανούπολις – Adrianoupolis / Edirne

Population

According to the 1878 Ethnographie des Vilayets d’Andrinople, de Monastir et de Salonique, Edirne had 16,220 households with about 58,000 male inhabitants in 1873. Turks made up the largest proportion followed by Greeks (about 16,000) and Bulgarians (about 10,000).[1] In 1905 Adrianople had about 80,000 inhabitants, of whom 30,000 were Turks, 22,000 Greeks, 12,000 Jews ,10,000 Bulgarians, 4,000 Armenians, and 2,000 more citizens of unclassified ethnic/religious backgrounds.[2]

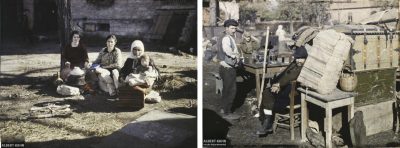

“On the eve of the war, 800 Armenian families (4,536 Armenians) were living in Edirne (…). They were concentrated in two inner city neighborhoods, Kale Içi and Ar Bazar, and also in the suburb of Kara Ağaç. The inhabitants of Kara Ağaç were truck farmers, whereas the Armenians who lived in the inner city were craftsmen, tradesmen, or railroad employees when they were not employed in tobacco manufactures.”[3]

Notables

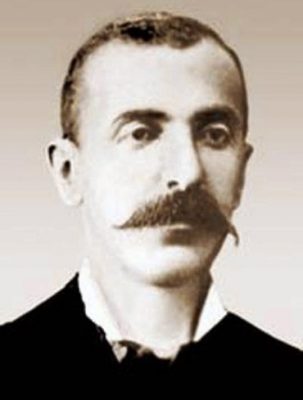

Hagop Paronyan (Յակոբ Պարոնեան – West Armenian: Baronian; 19 November 1843, Adrianople – 27 May 1891, Constantinople), Armenian writer, playwright, satirist, journalist, educator

History

Antiquity

The city was refounded by the Roman Emperor Hadrian on the site of the previous Thracian settlement Uskadama, Uskudama, Uskodama or Uscudama. Hadrian developed it, adorned it with monuments, and changed its name to Hadrianopolis. Licinius was defeated there by Constantine I in 324, and Emperor Valens was killed by the Goths there during the Battle of Adrianople in 378.

Medieval period

Around 790 to 800, the Adrianople became the center of the newly created Byzantine military-administrative district (theme) of Macedonia. In the following centuries, the rule over the city and the theme alternated between the Bulgarian and Byzantine Empires. In 812, the Bulgarians under Khan Krum of Bulgaria were victorious over Emperor Michael I Rhangabe in the Battle of Adrianople. The city was temporarily seized and its inhabitants deported to the Bulgarian lands north of the Danube. Tsar Simeon I reincorporated the province into the Bulgarian Empire in 914. In 927, after the 50-year peace agreement between the Bulgarians and the Byzantines, most of the subject again came under Byzantine rule.

In 1204 the Crusaders conquered the city, but it fell back into Bulgarian hands after the Battle of Adrianople of 1205. During the existence of the Latin Empire of Constantinople, the Crusaders were decisively defeated by the Bulgarian Emperor Kaloyan in the Battle of Adrianople (1205). In 1206 Adrianople and its territory was given to the Byzantine aristocrat Theodore Branas as a hereditary fief by the Latin regime. Theodore Komnenos, Despot of Epirus, took possession of it in 1227, but three years later was defeated at Klokotnitsa by Emperor Ivan Asen II of Bulgaria. After 1250 there was a last Byzantine period, and in 1362 the Ottomans under sultan Murad I Hüdavendigâr invaded Thrace and captured the city, probably in 1369. From 1369 to 1453 Adrianople was the second capital of the Ottoman Empire after Bursa.

Koca Mi‘mār Sinān Āġā (c. 1490 – 1588)

Born a Christian of probably Cappadocian Greek or Armenian descent in a small town called Ağırnaz near the city of Kayseri, the name of Sinan’s father is variously recorded as Abdülmenan, Abdullah, or Hristo (Hristos; Grk.: Christos). Sinan’s baptismal name was Joseph. Sinan entered his father’s trade as a stone mason and carpenter. One argument that lends credence to his Armenian or Greek background is a decree by Selim II dated Ramadan 7 981 (ca. 30 December 1573), which grants Sinan’s request to forgive and spare his relatives from the general exile of Kayseri’s Armenian communities to the island of Cyprus; while the British scholar and author of A History of Ottoman Architecture (1971), Godfrey Goodwin stated that “after the Ottoman conquest of Cyprus in 1571, when Selim II decided to repopulate the island by transferring Rum (Orthodox Christian) families from the Karaman Eyalet, Sinan intervened on behalf of his family and obtained two orders from the Sultan in council exempting them from deportation.”[4]

Another fact which supports the claim of Sinan’s Greek origin is his passion for the design of the Hagia Sophia, which has been the main source of inspiration for the design of most of his mosques.

According to Herbert J. Muller though, he “seems to have been an Armenian.“[5] Lucy Der Manuelian of Tufts University suggests that “he can be identified as an Armenian through a document in the imperial archives and other evidence.“[6]

In 1512, Sinan was forcibly conscripted into Ottoman service under the devshirme system. Following a period of schooling and rigorous training, Sinan became a construction officer in the Ottoman army, eventually rising to chief of the artillery. He was the chief architect and civil engineer for sultans Süleyman I (the Magnificent; reigned 1520-66), Selim II and Murad III. During a period of 50 years, he was responsible for the construction or supervision of every major building in the Ottoman Empire. More than 300 structures are credited to him, exclusive of his more modest projects.

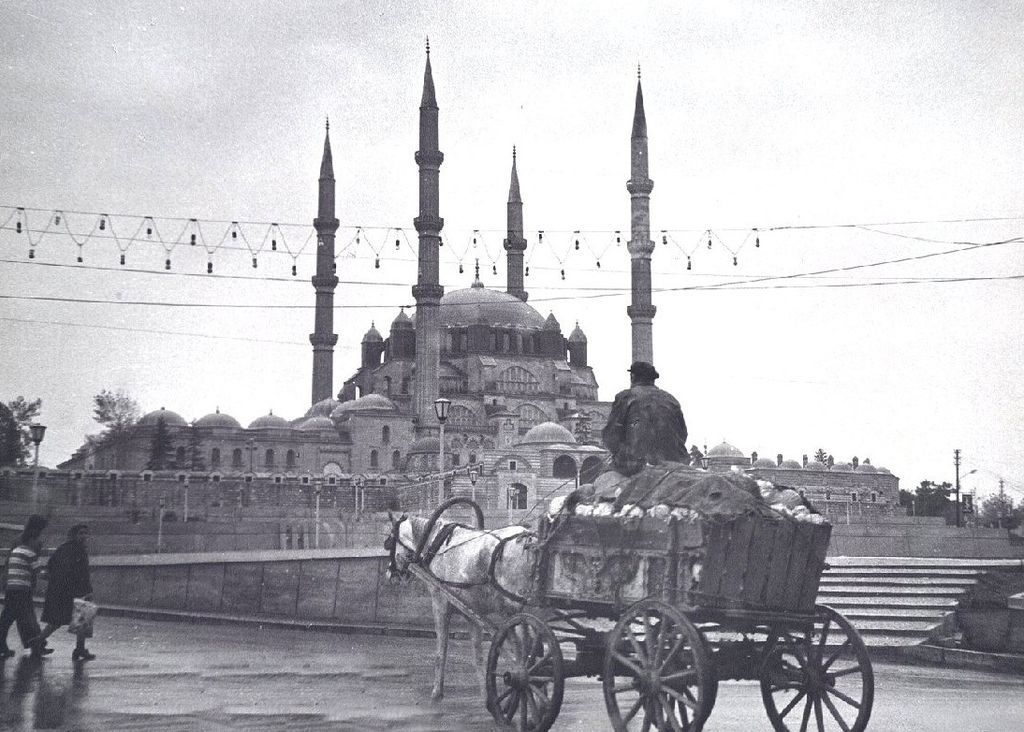

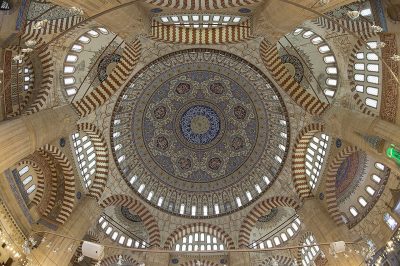

By 1550 Süleyman I was at the height of his powers. He gave the order to Sinan to build a great mosque, the Süleymaniye, surrounded by a complex consisting of four colleges, a soup kitchen, hospital, asylum, bath, caravanserai, and a hospice for travelers. Sinan, now heading a department with a great number of assistants, finished this formidable task in seven years. Although the Süleymaniye became his most famous work, Sinan himself considered his masterpiece to be the Selimiye Mosque in nearby Adrianople, built in the years 1569–75. This mosque is the culmination of his centralized-domed plans, the great central dome rising on eight massive piers in between which are impressive recessed arcades. The dome is framed by the four loftiest minarets in Turkey.

He supervised an extensive governmental department and trained many assistants who also distinguished themselves, including Sedefhar Mehmet Ağa, architect of the Sultan Ahmed Mosque.

In this work, Sinan is thought to have been influenced by the ideas of the Renaissance architect Leone Battista Alberti and other Western architects, who sought to construct the ideal church, reflecting the perfection of geometry in architecture. Sinan adapted his ideal to Islamic tradition, glorifying Allah by emphasizing simplicity more than elaboration. He tried to achieve the largest possible volume under a single central dome, believing that this structure, based on the circle, is the perfect geometrical figure, representing the perfection of God.

Starting with the Byzantine church as a model, Sinan adapted the designs of his mosques to meet the needs of Islamic worship, which requires large open spaces for common prayer. One of his motivations in this work was to create a dome even larger than that of the Hagia Sophia. As a result, the huge central dome became the focal point around which the design of the rest of the structure was developed. Sinan pioneered the use of smaller domes, half domes, and buttresses to lead the eye up the mosque’s exterior to the central dome at its apex, and he used tall, slender minarets at the corners to frame the entire structure. Four minarets—each 83 m high, the tallest in the Muslim world—are placed at the corners of the prayer hall, accentuating the vertical posture of this mosque that already dominates the city. This plan could yield striking exterior effects, as in the dramatic facade of the Selim Mosque. Sinan was able to convey a sense of size and power in all of his larger buildings. Breaking free of the handicaps of traditional Ottoman architecture, this mosque marks the apex of classical Ottoman architecture.

Sinan is considered the greatest architect of the classical period, and is often compared to Michelangelo, his contemporary in the West.

Excerpted from:

https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Sinan; https://www.britannica.com/story/sinan-the-ottoman-empires-master-architect; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mimar_Sinan

Modern period

Baháʼu’lláh, the founder of the Baháʼí Faith, lived in Edirne from 1863 to 1868. He was exiled there by the Ottoman Empire before being banished further to the Ottoman penal colony in Akka. He referred to Adrianople in his writings as the “Land of Mystery”.

Adrianople was briefly occupied by imperial Russian troops in 1829 during the Greek War of Independence and in 1878 during the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878. The city suffered a fire in 1905.

Adrianople was a vital fortress defending Ottoman Constantinople and Eastern Thrace during the Balkan Wars of 1912–13. It was briefly occupied by the Bulgarians in 1913, following the Siege of Adrianople. The Great Powers–Britain, Italy, France, and Russia–attempted to coerce the Ottoman Empire into ceding Adrianople to Bulgaria during the temporary winter truce of the First Balkan War. The belief that the Ottoman government was willing to give up the city created a political scandal in the Ottoman government in Constantinople (as Adrianople was a former capital of the Empire), leading to the 1913 Ottoman coup d’état. Although it was victorious in the coup, the Committee of Union and Progress under Enver Pasha was unable to stop the Bulgarians from capturing the city after the fighting resumed in spring 1913. Despite relentless pressure from the Great powers (Russia, Britain, France) the Ottoman empire never officially ceded the city to Bulgaria. Edirne was swiftly reconquered by the Ottoman empire during the Second Balkan War under the leadership of Enver Pasha (who would proclaim himself the “second conqueror of Adrianople”, after Murad I) following the total collapse of the Bulgarian military might in the region.

It was ceded to Greece by the Treaty of Sèvres in 1920, but recaptured and annexed by Turkey after the decisive Greek defeat at the end of the Greco-Turkish War in 1922. During the Greek administration, Edirne (officially known as Adrianople) was the capital of the Adrianople Prefecture.

Destruction

In 1919, the Ecumenical Patriarchate concluded: The Diocese of Adrianople “is the one that suffered the most from the atrocities of the Balkan War, the savage persecutions of 1914, and the consequences of the Turk and Bulgarian alliance of September 1915.

All that nature could devise in the way of unmerciful bastinado, unjustified arrests, imprisonment of peaceful, well-to-do people, with the sole object of extorting money from them, seizure of fortunes, requisitioning of houses and shops, etc., etc., all were put into practice, during the Bulgarian occupation of Thrace, with a view to exterminating the Greek element there, such action being not only tolerated, but also promoted by the highest Bulgarian officials.”[7]

For more information, see the section “Vilayet of Adrianople“.

Deportations and Forced Islamization of Armenians

Parallel to the mass arrests in Constantinople at the end of April 1915, numerous arrests were also made in Adrianople, as a report from the British Intelligence Service at the War Office of 5 May 1915 confirms: “(…) To this day the arrests of Armenians continue and it is said that all Armenian deputies and Oskan effendi, from the Ministry of Posts, have been arrested. In Adrianople also many arrests have been made.”[8]

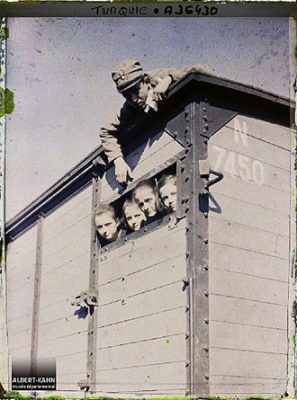

Basing on a report written of ‘common accord’ by the Bulgarian general consul M.G. Seraphimoff and the Austrian-Hungarian consul to Adrianople, Dr. Arthur Ritter (Knight) von Nadamlenzki, sent to the Austro-Hungarian embassy at Constantinople on 6 November 1915, scholar Raymond Kévorkian mentions first deportations of Armenians from Adrianople in late October 1915: “Departing from the methods employed in Anatolia, the local authorities here did not give the Armenians any time at all to prepare for the deportation. The order for immediate deportation was issued on the night of 27-28 October 1915, giving rise to acts of pillage that profited the local Ittihad club and Turkish schools. Three hundred Armenian shops in the Ali Paşa bazaar were demolished. (…) these deportees took the Istanbul-Konya-Bozanti route, by foot or rail, and ended up in Syria or Mesopotamia.”[9]

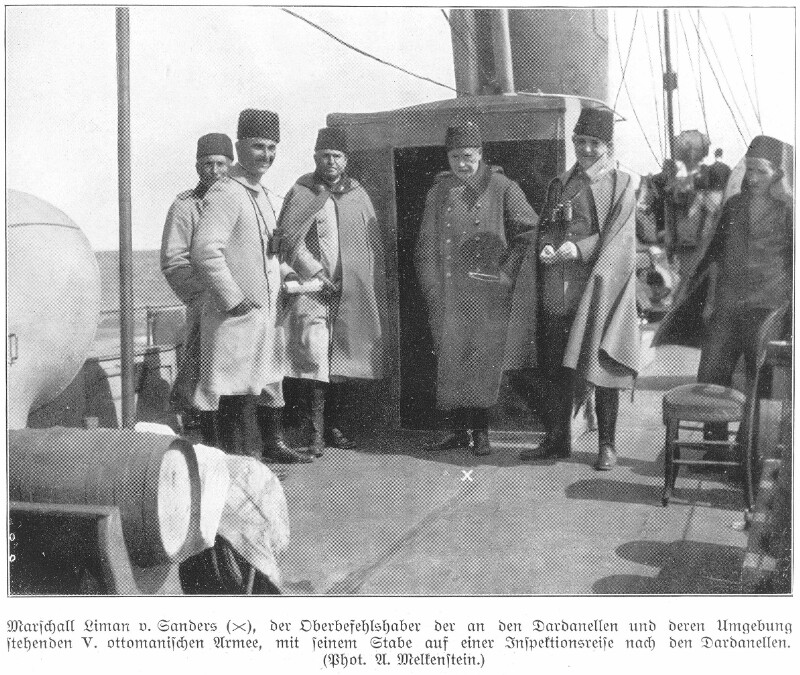

Otto Liman von Sanders, the head of the German Military Mission in the Ottoman Empire, testified as a defense witness in the criminal proceedings against the Armenian assassin Soghomon Tehlirian before the jury court of Regional Court III of Berlin on 2 June 1921. Among other things, he mentioned his intervention in favor of the Armenians and Jews of Adrianople in February 1916, whose deportation he claimed to have prevented at that time:

“I had the opportunity to intervene in February 1916, when the Vali of Adrianople also tried to expel the Armenians and Jews from Adrianople. I was notified by the Bavarian Lieutenant Colonel Willmer, went there, investigated the matter; our representation was the Austrian Consul [Dr. Arthur von Nadamlenzki; cf. above]. It was indeed true that the Vali had ordered the expulsion. I went to Constantinople and succeeded in having the matter stopped immediately; by the [Imperial German] Ambassador Count Metternich and the Ambassador [of Austria] Margrave Pallavicini.”[10]

However, and again according to R. Kévorkian, a “last wave of deportations, which targeted the families of craftsmen and soldiers, was carried out during the night of 17-18 February 1916 on the initiative of the interim vali, Zekeria Zihni Bey, formerly the mutesarif of Tekirdağ. It emptied the city of its last Armenians.”[11]

Liman von Sanders was in all probability deceived in his humanitarian intervention in February 1916, just as the Austrian Ambassador Pallavincini was deceived by Interior Minister Talat when Talat assured him that he would stop the forced Islamization of the Armenians and allow the Armenian families expelled to Rodosto to return to Adrianople. The effect of this conversation was as follows: “Yesterday the Kaimakam summoned the Armenians who had become Mohammedans and informed them that by order of Constantinople they were Armenians again, could use their old names and keep their former religion. Fearing expulsion, 40 families then sent a collective dispatch to the Minister of Interior [Talat] asking for permission to remain Mohammedans. But the families who should have returned to Adrianople did not arrive. Pallavicini wrote, ‘that Talaat Bey did not speak the truth when he told me that the families expelled from Adrianople had been taken to Rodosto. In fact, they had been deported to Asia Minor.’”[12]

The Austrian consul von Nadamlenzki reported in early March 1916: “The orders that have come from Constantinople on this matter this time seem to be more draconian. No exceptions are being made. Only conversion to Islam can save the unfortunate victims (…) from exile, that is, certain death. In order to save their lives, about 40 families have already submitted applications to convert to the Mohammedan religion. It must have been an infinitely sad sight yesterday when a crowd half mad with fear appeared at the Konak [government building] to renounce the faith of their fathers.” [13]

In all, in Adrianople 160 Armenians converted to Islam under duress. A. Nadamlenzki reported, “The widows and girls were immediately told that they would be married to Turks, while Turks were forced upon the young men. Thus, the Armenian community has been exterminated here. (…)”[14]

A report from the Information Service of the Navy in the Levant to the Ministry of the Marina, dated 21 February 1918, summarizes the fate of the Armenians of Thrace: “The Armenians of Thrace (Adrianople, Rodosto, Malgara), of Bithynia (Bahçecik, Adapazarı, Çengüler, Ovacık, etc.) and of Brusa (Bandırma, Balıkesir) were expelled via Aleppo along the line Izmit, Eskişehir, Konya, Pozantı.

The groups from Angora and Kastamonu, which consisted exclusively of men, as well as the population of Konya and Cesarea [Kayseri] joined this caravan.”[15]