Niğde is surrounded on three sides by the Taurus Mountains with the highest peak of Hasan Dağı in the region and the Melendiz River.

To the west lies the plain of Emen (Beyşehir district in Konya province), which opens into the vast plain of Konya. This is extremely fertile volcanic soil that provides Niğde with rich agriculture, especially apples and potatoes.

Administration

The Ottoman sancak of Niğde comprised the five kazas of Niğde, Nevşehir, Ürgüp, Aksaray, and Bor.

Toponym

The place name goes back to Hittite Nahita, Naxita or Nakida, in ancient Greek Nigdi.

History

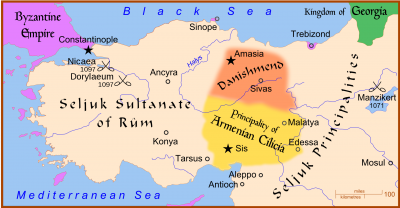

The area has been inhabited since the Neolithic period 8,000 – 5,500 B.C., as evidenced by excavations of burial mounds in the Bor district and the tin mines in the Çamardı-Keste district. Later, the Hittites settled here for a period of about 1000 years until about 800 BC. Then followed the Assyrians and Phrygians, Greeks, Persians, Alexander the Great and the Romans, who built the city of Tyana with its palaces and fountains; finally Turks from 1166 onwards.

The city of Niğde is thought by some historians to be on the site of Nakida, mentioned in Hittite texts. Niğde is located near a number of ancient trade routes, particularly the road from Kayseri (ancient Caesarea) to the Cilician Gates (Gülek Pass Gülek Pass). In the early Middle Ages, it was known as Magida (Grk.: Μαγίδα), and was settled by the remaining inhabitants of nearby Tyana after the latter fell to the Arabs in 708/709.

After the decline of ancient Tyana, Niğde and nearby Bor emerged as the towns controlling the mountain pass, a vital link on the northern trade route from Cilicia to inner Anatolia and Sinope (modern Sinop on the Black Sea coast).

By the early 13th century Niğde was one of the largest cities in Anatolia. After the fall of the Sultanate of Rûm (of which it had been one of the principal cities), Niğde was captured by Anatolian beyliks such as Karaman Beylik and Eretna Beylik. According to Ibn Battuta, ruinous, and did not pass into Ottoman hands till 1471.

Population

According to the Ottoman population statistics of 1914, the sancak of Niğde had a total population of 291,117, consisting of 227,100 Muslims, 58,312 Greeks, 4,935 Armenians and 769 Protestants. The demographics of the town of Niğde consisted of 52,754 Muslims, 26,156 Greeks, 1,149 Armenians and 137 Protestants.[1]

According to the census of the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople, there lived 5,727 Armenians in five localities of the sancak of Niğde on the eve of the First World War. They possessed four churches and one monastery.[2] “In the prefecture of the sancak of Niğde, 1,500 Armenians made a living as stockbreeders. Located close by, Bor had an Armenian population of nearly 900; 1,500 Armenians lived Aksaray, located in the northern part of the sancak, perhaps another 2,000 lived in Nevşehir. The total Armenian population of the sancak was thus over 6,000.”[3]

10 km behind the city is Eski Gümüş, a Byzantine monastery of Cappadokia with a columned rock church and very well preserved frescoes from the 10th and 11th centuries.

Destruction

A documentation by the Ecumenical Patriarchate, published in 1919, stated: “Until lately the province of Nigde has been spared, thanks to the good intentions of its Governor. Unfortunately the system of denunciation was introduced into this region also, a number of Christians became the victims of calumny at Nigde, Poro [Trk.: Bor], Kuldjouk, Hassa-keuy [Hasanköy?] and other places, and it is reported that still greater calamities will befall the Greeks in the near future, for the Vali of Konia [Konya], whose hatred against the Christians knows no bounds, accuses the latter openly of malevolence and treachery, and declares that it becomes imperative for the security of the State that this element be expelled from this territory, abandoning the fortunes they acquired by taking advantage, as the Vali pretended, of the simplicity of the Moslem element.

(…) Latterly, NIDGE has served as a centre through which drilled troops coming from Constantinople are sent to Erzeroum, and recruits coming from Cesaria are sent to Constantinople, lender pre-text, therefore, of accommodating the soldiers, the military authorities have now requisitioned the schools of Nigde which have cost so much in money and trouble.”[4]

During and after World War I, the kaza of Niğde – as the rest of the Konya province – became a deportation area for Greek Orthodox and Armenian Christians from other regions as well as an area whose Christian population was deported.

The German missionary and reverend Hans Bauernfeind, who had left the Bethesda Mission Station for the Blind in Malatya and was on his way to Constantinople with his relatives, noted on 20 August 1915 in Kayseri:

“(…) Yesterday we (…) only left at 7:30 a.m., then drove 5 hours through rather boring countryside to Sultan-Han, where we (…) took a break. (…) We also met Armenians again, namely men on ox carts. (…) Shortly before Caesarea [Kayseri] we met a mysterious procession of about 4-5000 Armenian men, who came from Nigde and were obviously not to be killed, but taken away for harvest or road work. For they all had haversacks on their backs, and in some cases beds as well. Behind them came ox carts, as it seemed to us, with agricultural implements.”[5]

Two days later, now in Bor, Bauernfeind mentioned the deportation of Niğde’s Armenian population, after having passed Niğde on 21 August 1915:

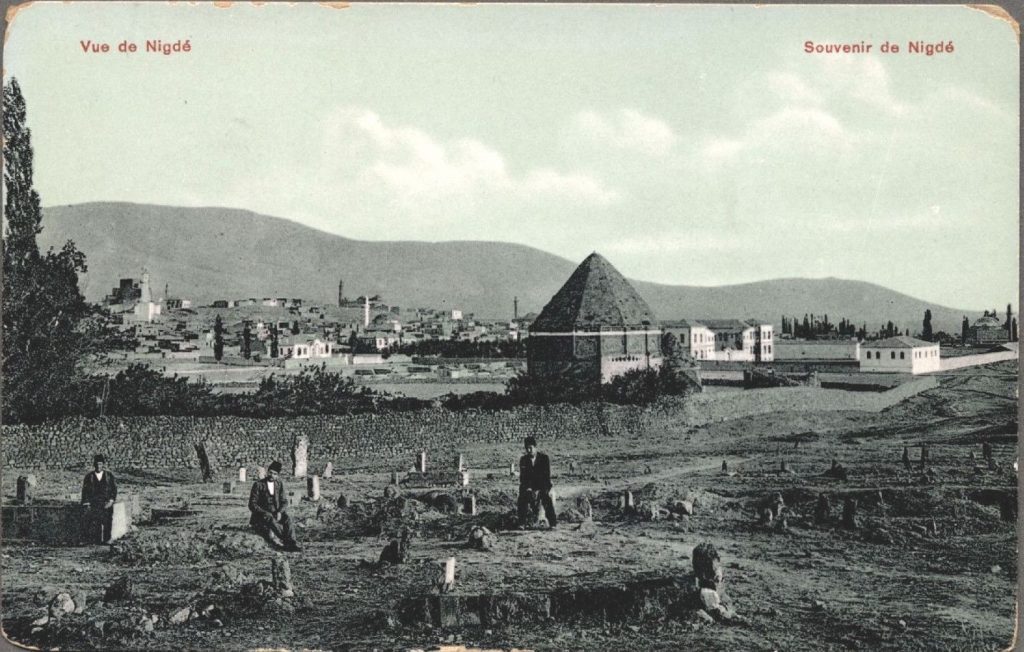

“ (…) At 9 o’clock we arrived in Nigde, a town of about 25-30000 inhabitants, one third Turks, one quarter Greeks. The Armenians, almost as many as Greeks, were all sent into exile. We had seen the men before Caesarea; the rest via Eregli to Yemen, is probably meant to Urfa. (…) Now it went over boring plain up to here (Bor, the ed.) also a not small city, where we arrived 12.05 and descended in the Han [karavanseray; inn]. (…) The road between here and Sivas is partly excellent, partly awful, partly in progress, partly unfinished,(…), in colorful confusion. Nevertheless, one must admire how much work has been done there during the war months by the Ameletabur (workers’ battalions, ed.). The previous night we again encountered a group of Armenian men. Even the young Chorush (cavuş: Turkish for sergeant, ed.) who accompanied us at night, an intelligent man, was of the opinion that they are mostly killed.”[6]

“Nazmi Bey, the kaymakam of Niğde, and Lieutenant-Colonel Abdül Fetah, the head of the deportation office in Aksaray, organized the massacres in Aksaray in late August. The Armenians of Nevşehir were deported to Syria in mid-August 1915 by the kaymakam Said Bey (…).” [7]

In the spring of 1920 and in 1922 deportations took place from Kayaköy (Grk.: Livissi; Spring 1920), Saraköy (1920), Bıyıklı, Yiambey, and Bağarası to Niğde.[8] Dr. Mark H. Ward, a physician working for the U.S.-based Near East Relief in Harput, observed on 28 September 1921 the transit of 125 deportees from Niğde, Karaman, Ereğli, Konya and Kayseri to Bitlis.[9]