Retreat to a Holy Mountain: The Bithynian Olympos and the Byzantine monasticism

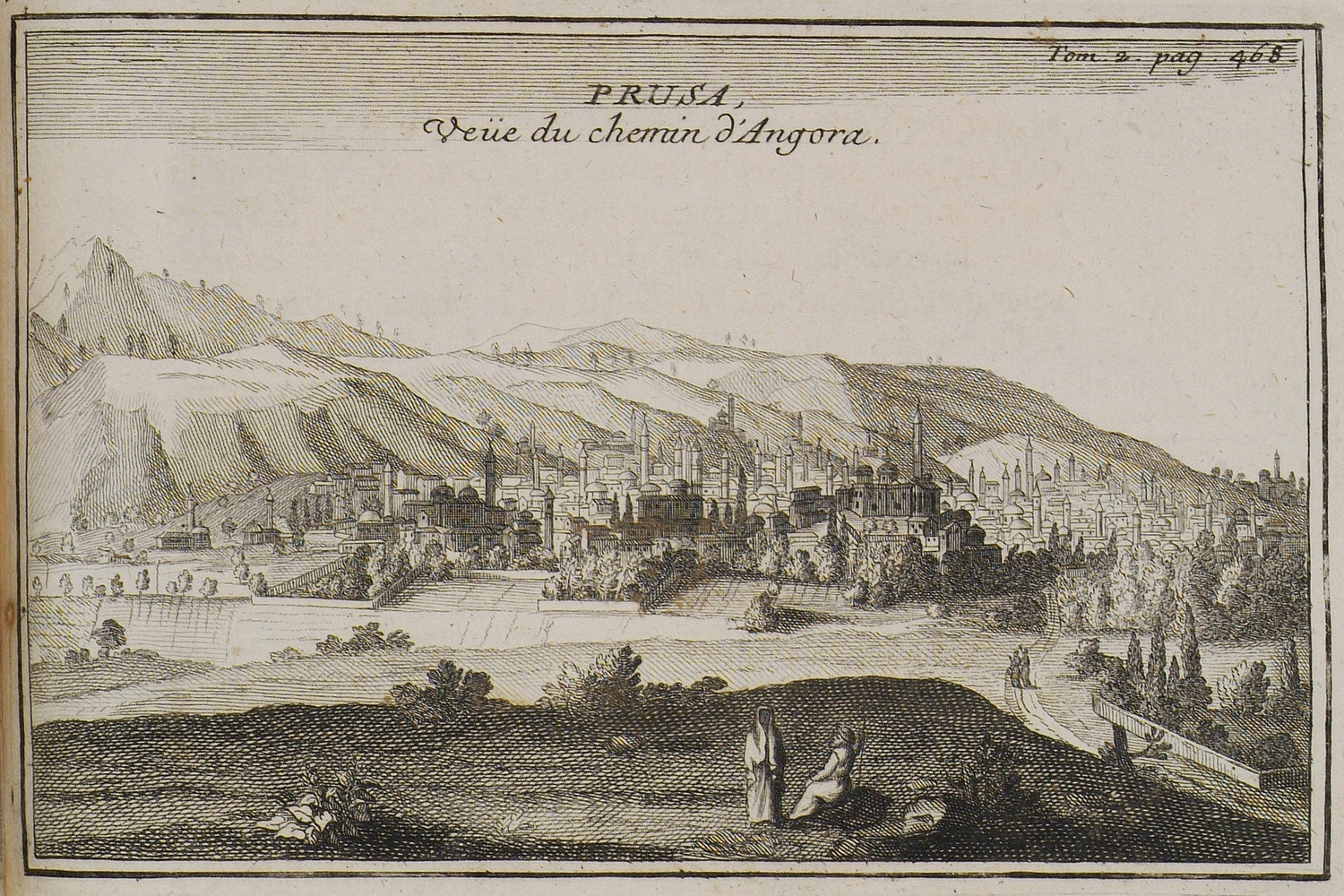

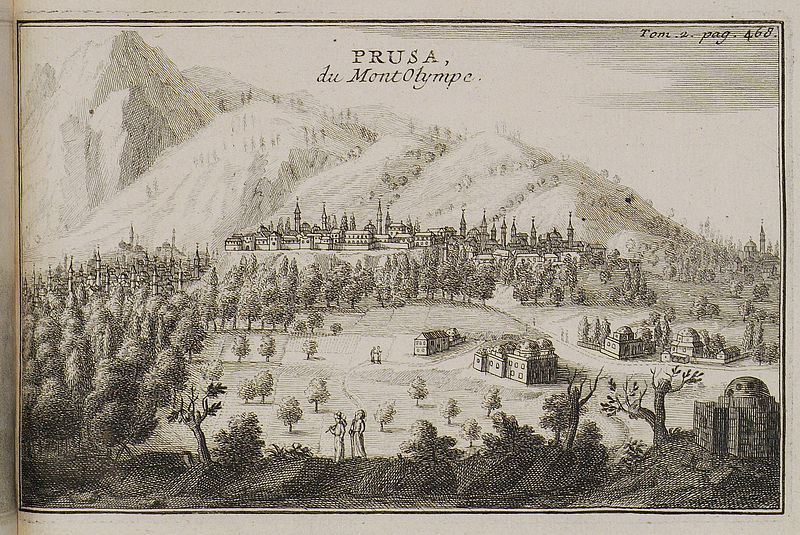

(…) Mount Olympos is with more than 2500 m above sea level the highest mountain of northwestern Asia Minor at all. In the summit regions there are high alpine conditions. From Prousa at the north-western end of Mount Olympos, the mountain range extends a good 40 km to the SE; the remote eastern parts, however, play no role in the sources of monasticism on Mount Olympos. In the eyes of the Byzantine sources (hagiographic and others), the size of Mount Olympos is at least doubled by the fact that the surrounding hills and plains are also considered to be part of it; so the monasteries in the whole area north and northwest of Prousa including the coastal strip from the mouth of the Ryndakos to Kios [Gemlik] could be called ‘at Olympos’, as well as the monasteries in the plain around Yenişehir north of the mountain range, which roughly corresponds to the landscape Atrōa. In a very broad definition of Olympos, even the studitic monasteries Kathara, Sakkudion and H. Christophoros in the Argantōnios mountains could be counted as being part of Olympos.

(…) In the greater area of Mount Olympos an exact location with archaeological remains could only be determined for a few monasteries, and these are all located on the coast outside the actual mountain area (Elegmoi, Mēdikion, Pelekētē, Megas Agros). The location of the Agaurōn monastery southwest of Prousa is approximately known. From some other monasteries we know at least the area where they are to be found; for example Antidion, H. Zacharias and other monasteries were located in the landscape Atrōa, which has now finally been located north and north-east of Mount Olympos.

(…) While Constantine V unceremoniously extinguished the monastic life on the Auxentios mountain by military means, Mount Olympos seems to have survived the first iconoclasm more or less unscathed (only one – probable – martyr is known); but the number of monasteries founded precisely at this time suggests that Mount Olympos may have served as a refuge, which, due to its vastness and impassability alone, was somewhat removed from military control by the central power. (…)

In addition to the geographical size of the area of the Bithynian Olympos, which provided space for a large number of monasteries, it was also the very different landscapes and altitudes that offered the hermits and monastic communities a range of different living conditions, different degrees of seclusion or access to the world (and the world to them) and different degrees of difficulty of asceticism. Especially the detailed Saints’ Vitae of the 9th century that we have from this area, especially the two Vitae of Iōannikios and those of Petros of Atrōa, which were mostly played during the second iconoclasm, show how the “heroes” of these biographies made use of the natural conditions. Iōannikios spent, like almost all great hermits, an apprenticeship in a koinobitic monastery, in this case in the monastery Antidion (on the N side of Mount Olympos, near the landscape Atrōa), before he built himself, with the permission of the abbot of Agaurōnklosters, as a hermit at the Agaurinon Oros (= Trichalix) above the monastery a small cell, where he spent 13 years. Because of the many visitors who came to him without interruption, he spent some time in the theme Thrakēsion, but soon returned to settle down deeper in the mountains this time. But here too, as with the first hermitage, relations with the Agaurōn monastery were close and the general visitors were numerous. As often as Iōannikios settled down again on Mount Olympos (at first again above the Agaurōn Monastery, towards the end of his life above the Antidion Monastery), his dwellings were such that they offered difficult living conditions, but remained accessible for visitors, even sick ones.

(…)

The heyday of Mount Olympos as a monastic mountain, which began with the foundations of the iconoclastic period, and the prestige, which was certainly also based on the role in the struggle of famous abbots and hermits against iconoclastic politics, lasted until the first half of the 11th century. It was during this period that most monasteries were mentioned, it was during this period that emperors (Leōn VI and Constantine VII) visited Mount Olympos, and in the 10th century Mount Olympus is always mentioned in the various lists of monastic mountains to be dealt with in connection with the third monastic mountain, Kyminas. An unsolved – and due to our limited source base also unsolvable – problem seems to be the question of superordinate structures such as monastic associations or even approaches to a hierarchical form of organization on Mount Olympos. The so-called Studitic Federation under the leadership of the Studiu Monastery in Constantinople included (though not all at the same time) the monasteries of Kathara, H. Christophoros, Tripyliana, Sakkudiōn and probably Symboloi, which can only be counted to the outermost perimeter of Mount Olympos. Also Petros of Atrōa collected a group of monasteries under his leadership (center was H. Zacharias), which were only partly located at or around Mount Olympos, but for the most part in Lydia, Asia and Phrygia; they seem to have dissolved with his death (837). Also the real function of the “Archimandrite of Olympos”, who is known from two letters of Michaēl Psellos and a grave inscription of the year 1196, remains unclear.

Although individual monasteries survived, the time of Olympos as a holy mountain probably came to an end in the course of the later 11th century, but certainly in the 12th century. Apart from the fact that there were apparently no more outstanding “holy” personalities, the form of monastic life that had established the fame of Olympos, namely the form of Laura, mixed from koinobitic and eremitic elements, lost its importance during this period. Thus, the more koinobite-oriented and economically more interesting monasteries around Mount Olympos survived longer than the Laura, which were often situated higher up in the mountains.

No source informs us concretely about the destruction of monasteries by the Turks, which only a few years after the battle of Mantzikert (1071) overran even Bithynia; monasticism in the area of Mount Olympo

s could never recover from this blow, not even in the relatively peaceful times of the empire of Nikaia.

With kind permission of the author excerpted and translated from his essay: Klaus Belke: Heilige Berge Bithyniens. In: Soustal, Peter (Hg.): Heilige Berge und Wüsten: Byzanz und sein Umfeld; Referate auf dem 21. Internationalen Kongress für Byzantinistik, London 21. – 26. August 2006. Wien: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 2009 (Veröffentlichungen zur Byzanzforschung, Bd. XVI; Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Philosophisch-Historische Klasse, Denkschriften, 379. Bd.), p. 16-20. https://www.academia.edu/1402508/Heilige_Berge_Bithyniens_in_P._Soustal_Hrsg._Heilige_Berge_und_W%C3%BCsten._Byzanz_und_sein_Umfeld._Referate_auf_dem_21._Internationalen_Kongress_f%C3%BCr_Byzantinistik_London_21._26._August_2006_VBF_16_%C3%96AW_Phil.-hist._Kl._Denkschr._379_._Wien_2009_15_24

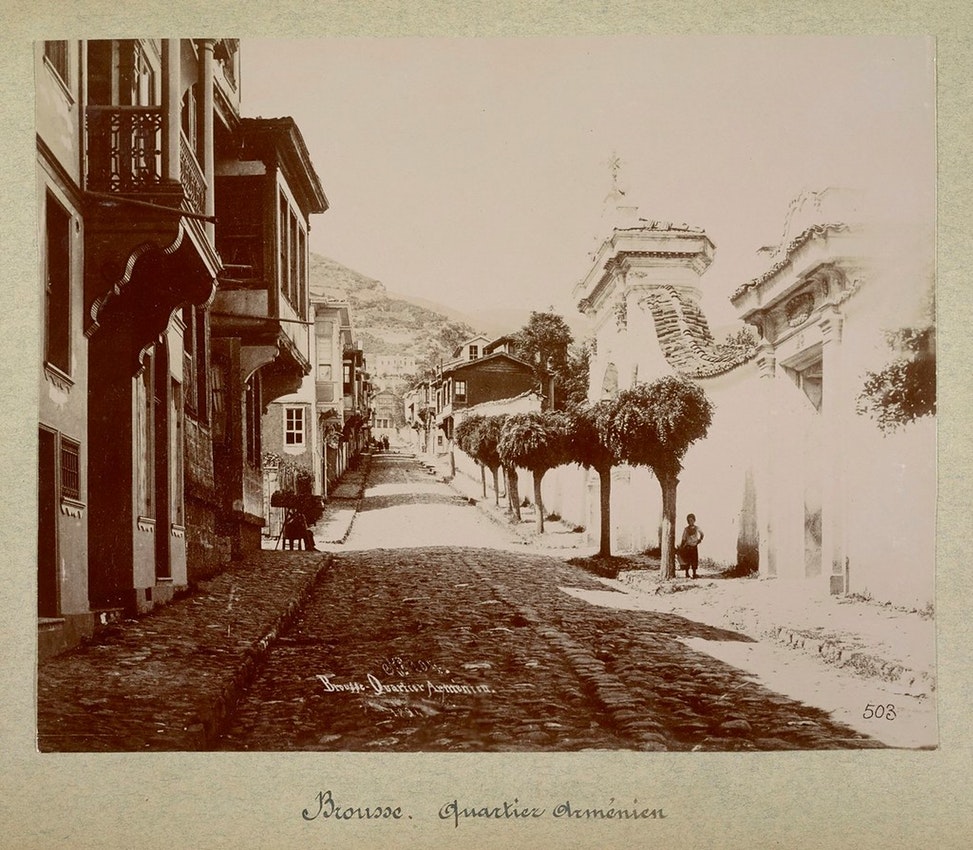

Prousa (Bursa) City

The city of Prousa (also Brusa; Tr: Bursa) was established ca 200 B.C. by King Prousias of Bithynia, and came under Roman control in 74 B.C. Prousa was briefly renamed Theoupolis (‘God’s City’) in the seventh century. After a long siege, Prousa was occupied by the Ottoman Turks on April 6, 1326 and became their capital, until they chose Adrianople as their capital in 1413. In 1402, Prousa was sacked by the army of Tamerlane (Timur ‘Lenk’).

In 1920/21, the area was occupied by Hellenic forces, with Prousa being occupied on June 25, 1920. The Hellenic army withdrew from the area after their defeat in late August 1922 (Prousa itself was held until August 28, 1922), and all Orthodox were evacuated to Greece or killed by the advanced Turkish forces.[1]

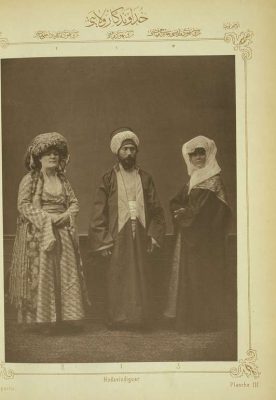

“Bursa was and still is one of the most important towns in Western Asia Minor. It traces its origins to early antiquity. In 1326, the Ottomans captured Bursa and made it their first capital until it was lost temporarily in 1402 to Tamerlane, whose army plundered and burned the city. Even after the Ottomans transferred their capital to Adrianople (Edirne) and later to Constantinople (Istanbul), Bursa remained an important city and was used as a base of operations for launching military campaigns in the east. It was the capital of the sanjak and later of the eyalet and then vilayet of Khudavendigar (Hudavendigar).”

Source: Hovannisian, Richard G.; Manuk-Khaloyan, Armen: The Armenian Communities of Asia Minor: A Pictorial Essay, in: The Armenian Communities of Asia Minor; ed. R. G. Hovannisian (Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 2014), p. 23

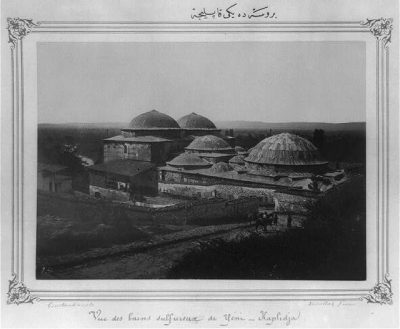

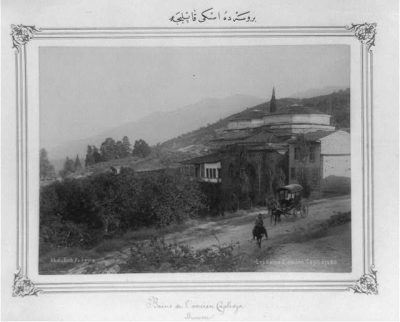

„Brusa, in the Vilayet of Brusa, at the foot of the Mysian Olympus and some 90 kilometers south of Constantinople (…) is the principal center of silk production in Turkey and its chief industry is silk spinning. It is also a watering resort of more than local fame; its hot springs, where Roman noblemen of old used to take their ‘cures,’ possess qualities which are pronounced unsurpassed.”

Source: Ravndal, Gabriel Bie: Turkey: a Commercial and Industrial Handbook. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1926 (Department of Commerce, Trade Promotion Seriec, No. 28), p. 15

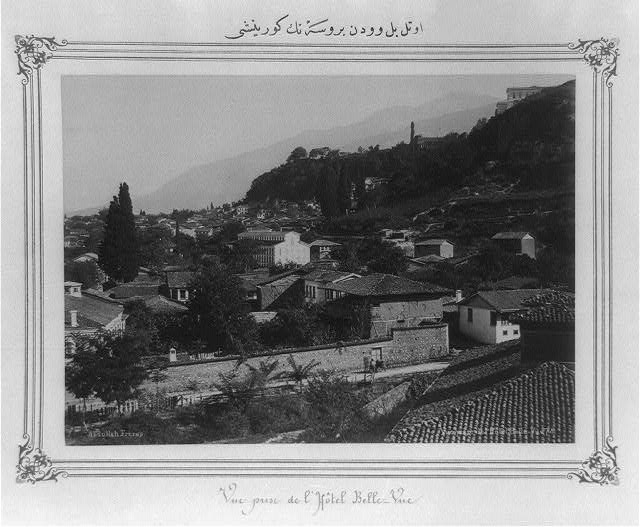

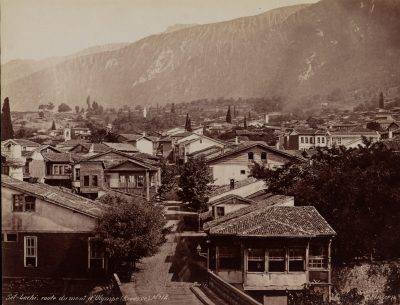

View on Bursa, from the Bellevue Hotel (Photograph: Abdullah Frères, 1880. Source: Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/)

Population

“According to the official Ottoman yearbook (salname) for the year 1892, the town of Bursa boasted a population of 76,000 inhabitants, of whom 7,541 were Armenians (most of whom lived in the Setbashi, Kurtoghlu, and Emirsultan quarters), 5,158 Greeks, and 2,548 Jews. Many Muslims from the Caucasus (mainly Circassians) who fled from Russian rule settled in Bursa, as did a number of Bulgarians following the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-78.“(2)

Armenian Population

“Located some 20 kilometers from the Sea of Marmara at the foot of Mt. Olympus, the city of Bursa had until 1915 an Armenian population of 11,500 settled mainly in the Setbaşi and Emir Sultan neighborhoods. The city’s Armenians and Greeks represented more than one third of its population, which also included a large number of muhacirs who had recently come from the Balkans. The Armenian colony of Bursa, founded prior to the fifteenth century, grew considerably in the early seventeenth century with the arrival of exiles fleeing the Turkish-Russian wars.

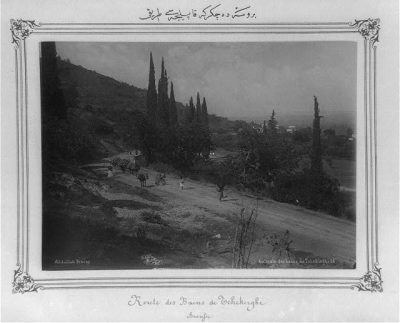

Bursa’s prosperous Armenian community possessed, in the middle of the Setbaşi neighborhood, a group of buildings, including a cathedral, a large lycée, and elementary schools. The Armenians’ main economic activities were silk-making, diamond-cutting, tapestry-making and the production of gold jewelry. Their summer residences were located in the suburb of Çekirge, with its hot springs and spa.”

Source: Kévorkian, Raymond: The Armenian Genocide: A Complete History. London, New York: I.B. Tauris, 2011, p. 557

“The first Armenians to settle in the Bursa district are said to have been fugitives fleeing from the Armenian kingdom of Cilicia, which fell to the Mamluks of Egypt in 1375. Armenians continued to move to Bursa both before and after the Ottoman capture of Constantinople in 1453. It is believed that a medieval Armenian Bible copied during the reign of Cilician King Hetum was brought to the city by the first wave of Cilician Armenian immigrants and housed in the local Armenian church. As has been noted, the Armenian bishop of Bursa is said to have been summoned to Constantinople to establish the Armenian Patriarchate in the Ottoman capital.”

Source: Hovannisian, Richard G.; Manuk-Khaloyan, Armen: The Armenian Communities of Asia Minor: A Pictorial Essay, in: The Armenian Communities of Asia Minor; ed. R. G. Hovannisian (Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 2014), p. 23

Silk Trade, Manufacturing and anti-Christian Violence

“Given its close proximity to the Sea of Marmara, Bursa developed into an international marketplace that offered a variety of goods arriving from both Western Europe and the Near East. The city’s rise as an economic emporium can be traced to the mid-fourteenth century. Silk was Bursa’s most prized commodity and its cultivation there dated to Byzantine times. Iranian merchants from the province of Azerbaijan (Tabriz) made their way to Bursa to sell their silk in exchange for Italian goods. The frequent caravans passing over the Tabriz-Erzerum-Tokat route brought the silk from the cities of Gilan, Astarabad, and Sari. Iranian Muslim merchants dominated the silk trade from the fifteenth to early sixteenth centuries, but they were gradually supplanted by Armenians. The names of Armenians are more frequently encountered in Bursa court records in the seventeenth century, presumably because of the special economic and financial privileges that Shah Abbas I granted them after his forcible deportation of much of the Armenian population from the Araratian plain between 1603 and 1605. Brocades and gold velvets were exported to Europe, Egypt, and Iran, but the Ottoman imperial court seems to have been the primary procurer of the silken goods. In the eighteenth century, Bursa’s silk industry declined in face of better quality silk produced in Europe and Izmir, but in 1837 steam power was introduced in the city and within two decades the number of filatures (reels used for drawing silk from the cocoons) had risen to thirty-five, capable by the eve of World War I of producing 1,000 tons annually.

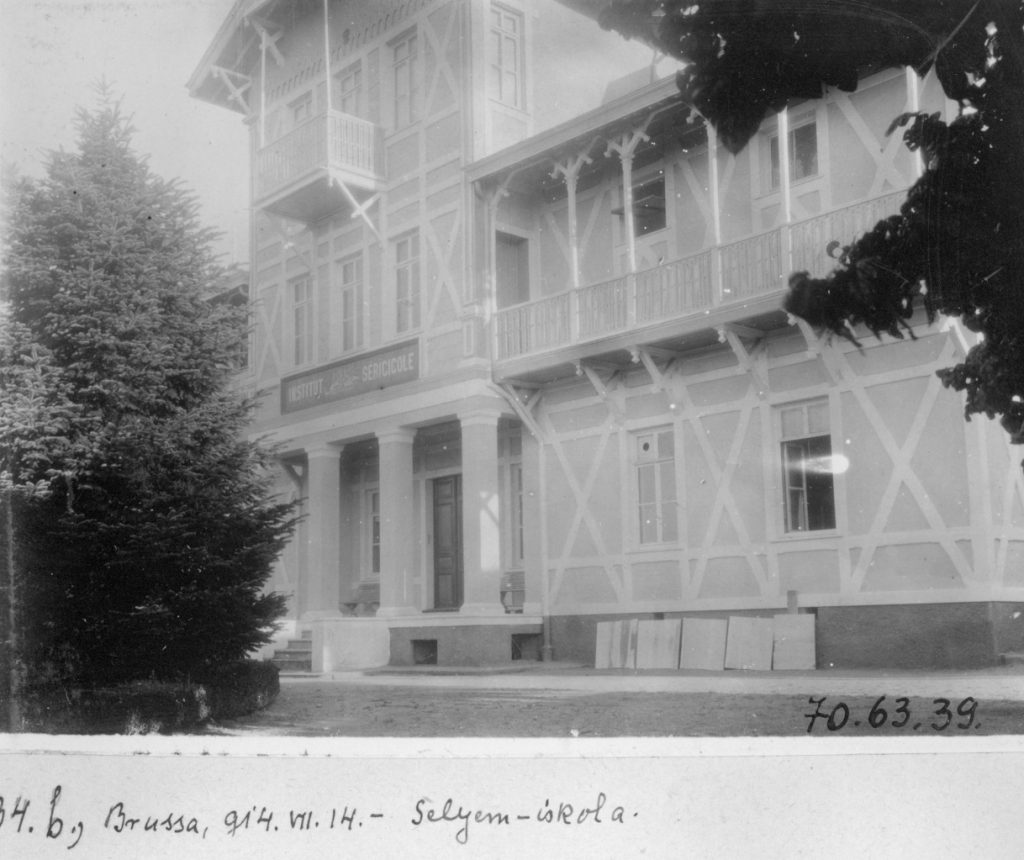

In 1847, there were three mills in Bursa, one of which was constructed and operated by an Armenian. Other factories were later established in the city’s Greek and Armenian quarters. As industry developed in the mid-nineteenth century, a considerable number of young Armenian girls entered the workforce as reelers. The Bursa Sericulture Institute, which was co-founded by an Armenian in 1888 and funded by the Ottoman Debt Administration, introduced formal instruction in silk cultivation. By the turn of the twentieth century, Armenians and Greeks made up more than 70 percent of the silk cultivators. But the proliferation of mills also became a source of friction among Bursa’s ethnic groups. It is believed that the erection of a building on the grounds of a Muslim cemetery in Bursa by an Armenian mill operator served as a catalyst in 1862 for the outbreak of Muslim rioting and violence directed against the town’s Christian minorities.”

Source: Hovannisian, Richard G.; Manuk-Khaloyan, Armen: The Armenian Communities of Asia Minor: A Pictorial Essay, in: The Armenian Communities of Asia Minor; ed. R. G. Hovannisian (Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 2014), p. 23ff.

Helmuth von Moltke: Journey to Brusa

Pera, 16 June 1836

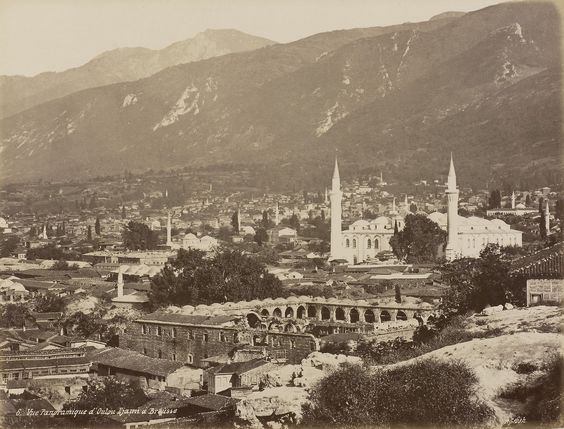

“(…) Everything here is cultivated, less with grain than with vines and mulberry trees. The latter are kept low as bushes and are decapitated like our willows to serve as fodder for the silkworms. Their large, light green leaves cover the fields far and wide. The olive tree forms a considerable woodland here, but it is planted. The entire richly cultivated area is reminiscent of Lombardy, especially the hilly region of Verona. As lovely as the foreground of the painting is, so splendid is the view from afar. On one side you can see the Sea of Marmara with the Princes Islands and on the other the splendid Olympus, whose snow-covered head was above a wide belt of clouds. (…) After we had crossed a low range of hills, we saw Brusa stretched out in a large green plain at the foot of Mount Olympus. It is indeed difficult to decide which of the two capitals of the Ottoman rulers has the more beautiful location, the oldest or the newest, Brusa or Constantinople. Here is the sea, there is the land that enchants; one landscape is in blue, the other in green. Against the steep, darkly wooded slopes of Olympus there are more than a hundred white minarets and vaulted domes. (…)

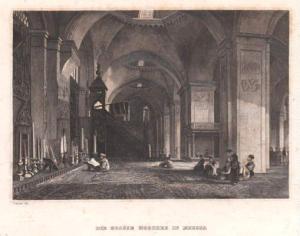

The largest of the mosques is a former Christian cathedral; it gets its light from above, with the central building completely open (…). When the Ottomans conquered the provinces of the Eastern Roman Empire, they kept the Greek architecture of the churches, but added the minarets of Arab origin. (…)“

Source: Moltke, Helmuth von: Unter dem Halbmond: Erlebnisse in der alten Türkei; 1835-1839. Berlin: Verlag Neues Leben, 1988, p. 107ff.

Η Προύσσα (I Prousa) – Praise to Bursa

I Prousa(3)

Bursa

Destruction

Starting in 1914, the Christian population of Bursa suffered from the anti-Greek boycotts. In Bursa, the Ecumenical Patriarchate at Constantinople reported, “Turks armed with clubs, and paid for the purpose, scoured the marketplace, threatening and ordering the [Greek] shop keepers to close. . . . Peasants on their way to Broussa, for the sale of their products there, were daily arrested and plundered. The same thing happened to the villages of Triglia, Siyi, and Moudania [Mudanya]. (…) During the European War, the boycott was no longer considered an effective measure against the inhabitants of the Greek element. The C.U.P. changed their policy, their plan being this time to deport the Greeks to Turkish villages, where they would in time become amalgamated with the Turkish element, and loose by degrees both their language and their religion. This plan was acted upon ever since June 1915.”[4]

The 1915 Eliticide

As early as 15 April 1915, searches and arrests of the local Armenian elite started. Teachers and notables were interrogated by the provincial chief of police, Mahmut Celaleddin, and Mehmet Ali, the senior investigating magistrate. In the end of May, some 200 notables were then transferred to Edrenos (Adırnas; Gr: Atranos; today Orhaneli), south of Bursa City, while others were sent to Bandırma (Greek: Panderma) for court-martial.

The arrival of Mehmetce, a Unionist delegate from the First Division of the Department for State Security at Bursa in early July not only marks the beginning of the forced expulsion of Armenians from the province, but also the end of the eliticide:

“On 22 July, Mehmedce Bey, accompanied by çetes [irregulars] of the Special Organization, went to Orhaneli, where some 400 men were held. Their liquidation began the next day. Every day they were taken in groups of 40 to the Karanlık Dere gorge, where they were shot by çetes, who then burnt their bodies. Among the victims were many merchants: Antranig Hanjian, Onnig Batlayan, Abraham Nalbandian, Hagop Kapujian, Toros Pekmezian, Karnig Pekmezian, Stepan and Levon Dingiuilian, Lutvig Lutfian, Minas Keuleyan, Hrant Arabian, Azniv Philibelian, Onnig Philibelian, Gabriel Michigian, the Lapatians, father and son, and Simenet Bedros Shamanian. Among those shot were also state officials and members of the liberal professions, teachers and craftsmen: Minas Findeklian (an employee at the Banque Ottoman) Harutiun and Armenag Luftian (pharmacists), Mihran Luftian (an elementary schoolteacher), Artine Uzunian (a lawyer), Stepan Hisian (a secretary), Mikayel Hanjian, Sarkis Michigian (a student), Piuzant Morukian (a student), Eduard Beyazian (an official in the Office of the Public Debt), Karnig and Garabed Pachajian (butchers), and Krikor Andonian (an official in the Department of the Public Debt).

Around the same time, the 100 men interned in the prison of the Bandırma court-martial, including 20 notables from Bursa who had been incarcerated since late April, were condemned to death or prison terms. The prelate of Bursa, Barkev Tanielian, and Sukias Diulgerian were condemned to five years in prison and then deported to Der Zor, where they died of typhus a few weeks later. As for those condemned to death, they were brought back to Bursa and finally hanged on 24 October 1915. The hanged men were Dr. Stepan Meliksetian (a physician) Pardunag Ajemian (a pharmacist), Simonig Seferian (a commission agent), Misak Mermerian (a goldsmith), Misag Der Kerovpian, Krikor Beoliukian, and four peasants; they were symbolically hanged on the Setbaşi Bridge, at the entrance to the old Armenian quarter.”

Source: Kévorkian, Raymond: The Armenian Genocide: A Complete History. (London, New York): I.B. Tauris, 2011, p. 558f.

Deportation

“The general deportations of Armenians in the province of Bursa began in the late summer of 1915. In July of that year, local officials, assisted by the Young Turk ‘Special Organization’, rounded up 400 Armenian men—professors, craftsmen, civil servants—and took them in groups of forty to the Karanalik Dere gorge, where they were summarily executed. Even though Bursa’s spiritual leaders were sentenced to a prison term of five years, they, too, were removed to Syria, where they soon contracted typhus and died. In September, the government announced that Bursa’s Armenian population as a whole would have to be evacuated and gave residents three days to prepare for the arduous trek. Armenian homeowners were called up to the local magistrate and told to sign a document that they had lawfully sold their homes to others. Wealthy Armenians were able to buy some time, but they were eventually deported all the same. Muslims refugees from the Russo-Turkish and Balkan wars pillaged Armenian homes or purchased what they wanted at prices far below their market value.

Two women at the American school, Annie T. Allen and Edith Parsons, attempted to aid and provide care for the exiles to the best of their ability. Protests lodged by the Americans against the mistreatment of the Armenians were met with indifference by the Turkish officials. The vali (governor) was reported to have said:

‘We are determined to get rid, once and for all, of this cancer in our country. It has been our greatest political danger, only we never realized it as much as we do now. It is true that many innocents are suffering with the guilty, but we have no time to make any distinctions [original emphasis]. We know it means an economic loss to us, but it is nothing compared with the danger we are thereby escaping!’

In a span of three days, 1,800 Armenian families from the Bursa vilayet were put on railroad cars and sent from Konia to Bozanti, on to Cilicia, and then onward into the vilayet of Aleppo (Halab; Haleb). The prelate of Bursa from 1912-14, the Very Reverend Sahag Odabashian (Sahak Otapashian), was sent on assignment to the interior provinces by the Armenian Patriarchate but was murdered in a small town near Sivas by mounted chete brigands belonging to the Young Turk Special Organization. Then, the new prelate, Barkev Danielian, was arrested and handed over to a court-martial. As in the other cases, most of Bursa’s Armenian population perished on the death marches or in exile.”

Source: Hovannisian, Richard G.; Manuk-Khaloyan, Armen: The Armenian Communities of Asia Minor: A Pictorial Essay, in: The Armenian Communities of Asia Minor; ed. R. G. Hovannisian (Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 2014), p. 25ff.

Angel Srapian (b. 1905, Bursa): Survivor’s Testimony

“At that time, I was ten years old. My sister was six months old, when we were deported from Bursa. On the way, we lost our relatives. Mother used to tell me, crying, ‘Look at the road, the dogs are eating the Armenians’ corpses, some of them are not even dead yet…’

On the road, my six-month-old sister fell ill. The women walking with us said to my mother, ‘You have neither milk nor bread to feed the child, put her by the road-side and let’s go on…’

Mother said, ‘No, I won’t.’ She tied the baby with a sheet to her back, and we continued our way. On the way, whether of hunger or fatigue, my mother lost her eyesight. Near Konya, we were robbed of our property. My mother cried with her blind eyes and said, ‘For God’s sake, at least leave us a quilt.’

‘We are God’, they said and began beating my mother.

On the road, we saw a cart. I begged, ‘Please, let my blind mother and the baby sit on this.’ The driver took pity and took us on the cart. We hard hardly gone a short distance when another cart came from the opposite side, they met on the narrow bridge, and our cart fell into the water. I caught the baby’s swaddles but I was in the water.

‘Alas!’ screamed my mother, ‘I have lost everything: my children also are gone!’

It was lucky that there were Armenian boys there. They said, ‘Don’t be afraid.’ They jumped into the water and rescued us…

We got out of the water; we were walking all wet. The officers gave orders from behind and from the front. Finally, we arrived at a station…

We had a relative that worked at the train station. We inquired after him. They said, ‘He will be here soon.’

The man came. In fact, it was the müdür [director; here: stationmaster] of the place. He told us to pass there night here.

We remained there until morning so as not to be driven on again. Mother’s eyes had started to see little by little. She cut my hair, blackened my face with charcoal because the Arabs and Turks kidnapped girls. She cut my hair like a boy’s. She took off my earrings; she dressed me like a boy.

That Armenian müdür helped us a lot. He sent us to Ereğli, not far from Konya. It took us nine days on foot. Mother worked here and there. From the railroad tracks we gathered pieces of coal to burn as at that time locomotives ran by coal. Pieces of coal that did not burn were thrown out and I gathered these with my brother. One day my brother fell into a sewage-pit… I saw that sewage was drawing him down; only his arms could be seen… I cried for help. People came and got him out. While taking him out, they injured his chin. I took my brother for a wash in the water. There was neither soap nor anything…

We remained in Ereğli for three and a half years. Mother sewed sacks; somehow we survived…

After the exile, the Armenians came and gathered children from the Turks’ houses. They had opened separate orphanages: one for the very young, another for girls, and one for boys.

The Armenian boys came from the army or the orphanages, chose a girl, married, and formed their families. The Americans opened factories. They ran weaving machines. The Armenian orphans worked there, or were sent to America. They took good care of the Armenian orphans.

My mother’s eldest brother had a small shop. He was a tailor and gave us a little help. One day, a Turk took possession of the shop and evicted my uncle. So, we were left completely helpless…(…)”

Source: Svazlian, Verjiné (ed.): The Armenian Genocide: Testimonies of the Eyewitness Survivors. Yerevan: “Gitoutyoun” Publishing House of NAS RA, 2011, p. 400