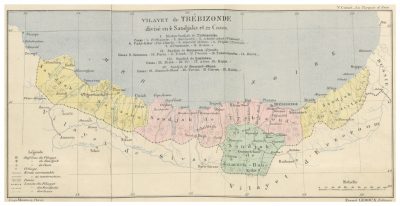

Administrative Division

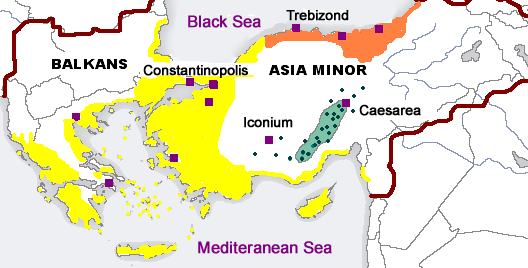

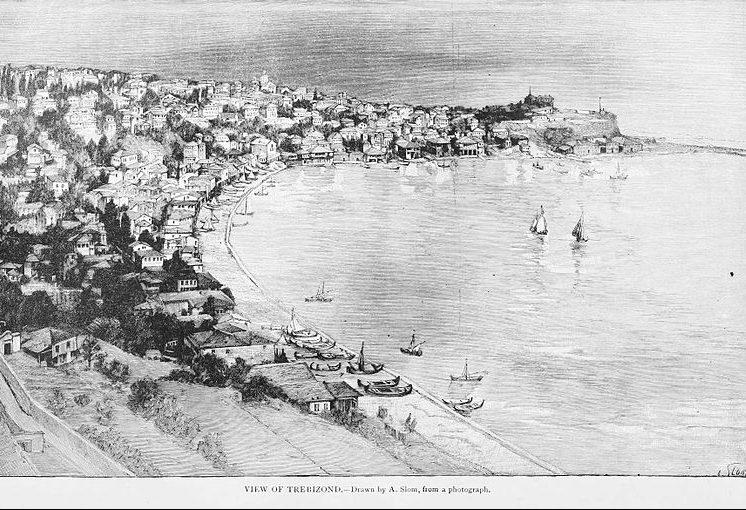

Located on the southern Black Sea coast and named after its capital, the province was created in 1867 in the course of the Ottoman administrative reform as the successor to the former Eyalet Trabzon and initially comprised the three sancaks Trabzon, Gümüşhane (Grk.: Agyroupolis) and Lazistan (Rize); this sancak in the very east of the province was created after the Russian-Ottoman war of 1877/8. In 1889, the sancak Canik with the capital Samsun was added to the west, so that the province covered a total area of 31,300 square kilometers with four sancaks and 22 kazas. Thus, the province included not only the narrow coastal strip but also the mountainous hinterland of the Pontos Mountains.

Population

In the 19th century, the number of Christians in the province of Trebizond fell sharply. When, as a result of the Berlin Congress (1878), Russian forces withdrew from the Batumi, Kars and Ardahan areas, there was a mass exodus of over 100,000 Greeks and Armenians from the eastern Pontos area.

In 1900 the population was 1.2 million; the first Ottoman census of 1885 (published in 1908) showed a population of 1,047 million. At the 1914 census, 921,128 inhabitants were Muslim, 161,524 Greek Orthodox and only 38,899 Armenians (Armenian Apostolic).

Armenian Figures

In contrast, the Armenian Apostolic Patriarchate of Constantinople indicated the number of Armenians in the province on the eve of the First World War at 73,395 in 118 localities. At that time the Patriarchate owned 106 churches and 31 monasteries in the province of Trabzon, and maintained 90 schools for 9,254 pupils.(1)

Greek Figures

As to the low figures officially given for the Greek Orthodox population of the Trebizond Province, the jurist Aristotelis Neofytos of Kerasunt (Tr.: Giresun) commented: “According to the last official almanac or yearbook (Salname) of the year 1321 (1904), the governmental district of Trebizond has 1,254,816 inhabitants, of whom only 194,169 were described as Greeks, i.e. only 2/5 of the actual total number. This is due to the fact that the Turks are only interested in the Turkish population because of the military service, whereas the Greeks, who were not called up for military service before the last war, did not have the births entered in the civil registry books in order to avoid paying the military service substitute tax. (…) In my calculations based on the list of the Turkish Yearbook of Population Increase, I found that at the beginning of the war (1914), the Greek population of Trebizond county was certainly 485,000 souls, compared to (…) about 850,000 or 900,000 Muslims of all nationalities, including the Stavriots.”[2] A somewhat higher estimate by Dimosthenis Oikonomidis (Ikonomidis) assumes 530,000 Greek Orthodox in the province of Trebizond.[3]

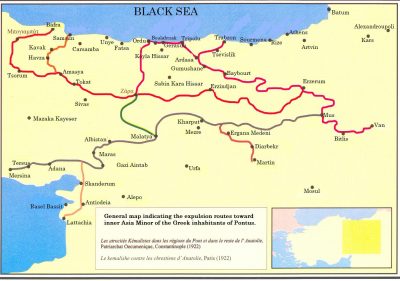

According to the statistics by Panaretos, abbot of the Monastery of St. John of Vazelon, there lived 697,000 Orthodox Greeks in the provinces of the six dioceses of Pontos in 1913. The Ecumenical Patriarchate and the Hellenic Foreign Ministry gave an overall number of 696,495 Orthodox Greek and Turkish-speaking Christians living in Pontos in 1914. 353,000 of these were murdered by the Young Turks and Kemalists between 1916 and 1923. 182,000 came to Greece, the rest escaped to Russia, which was dominated by civil war.(4) The statistics provided by Panaretos in 1920 mainly based on ecclesiastical sources and consular documents. In his official report to the Hellenic Ministry of Foreign Affairs, he wrote that the territory of Pontos included the prefecture of Trebizond and certain borderline areas of the prefectures of Erzurum and Sivas, populated by Greeks; he gave an overall population in Pontos in 1914 of 1,767,495; of these, 929,895 were Greeks, including 233,400 Islamized ethnic Greeks.[5]

The Centre for Asia Minor Studies has identified 1,454 villages in Pontos. At that time, there were 1,890 functioning Greek-Orthodox churches, 22 monasteries, 1,647 chapels and 1,401 schools with 85,890 pupils in all.

According to the Eumenical Patriarchate, the Greek-Orthodox Diocese of Trebizond consisted of 73 communities with 58,734 inhabitants.(6)

The Muslim population in the western half of the province of Trabzon consisted mainly of Sunni Turks, in the east of Lazes, the Christian population of Greek Orthodox and Armenians. Parts of the Greek and Armenian population were Islamized during the Ottoman rule of the Black Sea region, but preserved their Greek and Armenian languages. During the forced resettlement of the Christian-Greek population (Trk.: rumlar) to Greece in 1923, Islamized Greeks were refused permission to leave the country, even if they so wished.

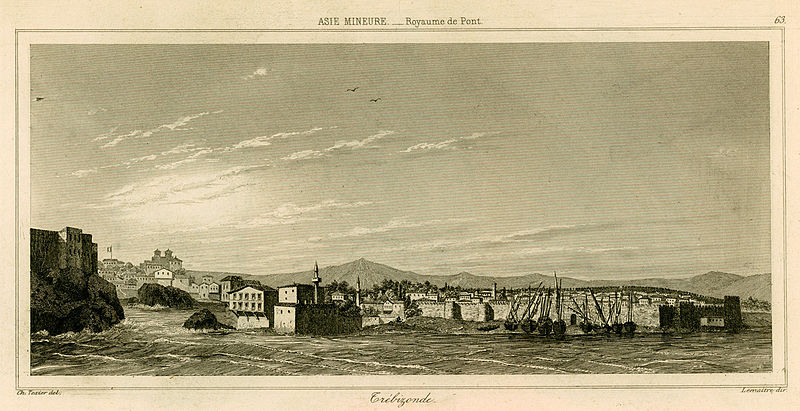

Bryson, Robert M. (lithographer; Source: Victoria and Albert Museum, London; Prints & Drawings Study Room, level D, case SC, shelf 47)

History

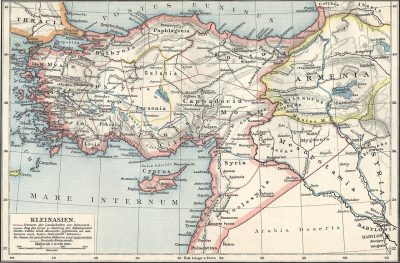

The Ottoman province of Trabzon comprised the territories of the ancient regions of Paphlagonia and Pontos. In the second half of the 19th century, the main area of Pontos was made of the vilayet of Trebizond but also comprised parts of the adjoining provinces of Sivas and Erzurum. The northern border of Pontos started to the west of Sinope and stretched as far east as the Russo-Turkish border. The southern border began from Inepolis and ran through Amaseia (Amasya), Tokat, Nikopolis, Argyroupolis (Trk.: Gümüşhane), Paipurt (Bayburt; Arm.: Baberd), the Soganlou Dag mountain range and ended at the Russo-Turkish border.

The region of Pontos was made up of six ecclesiastical provinces, namely Trapezunta, Rodopoleos, Chaldia, Neokaisarea (Niksar), Amaseia and Kolonia.

Greek sailors from Ionia founded secondary colonies in the Mediterranean and Black Sea in the first millennium B.C. These colonies included the present-day cities of Antibes and Marseilles in France, Katania and Messina in Sicily, Ischia and Naples in Campania and Italy respectively. All the cities founded in Pontos – Sinope, Trapezos, Amisos, Kerasus, Rizaion – as well as the cities on the east and north coasts of the Black Sea can be traced back to Ionian colonies, such as Nymphaion near today’s Kerch in Crimea, the ‘twin city’ of Dioscuria – the Abkhazian port and capital Аҟəа (Georgian: Sukhumi) – and the present-day city of Azov on the Azov Sea and the mouth of the Don River, which the Ionians called Tanais. The Roman Cicero compared the Greek coastal towns with a “hem that was attached to the vast fabric of the barbaric lands”.

In their search for mineral resources, Greeks from Asia Minor moved from the coasts of the Aegean, the Sea of Marmara and Pontos to the interior, for example to Cappadocia and Phrygia. The Greeks, who did not come as conquerors but by sea trade routes, often settled in or near more ancient settlements which had existed since the Bronze Age and which were descended from the Hittites, Minoans, Mycenaeans or indigenous peoples.

The Pontic Kingdom (281 to 63 B.C.)

Under the rule of originally Persian nobles who adhered to Hellenistic-Iranian cults, the independent kingdom of Pontos had its capital between 283 and 181 B.C. in Amasia (Amasya), followed by Sinope.

The traces of the ancestors of the ancient Pontic (Mithridatic) kings lead to Kios (Gemlik), a small town on the southern shore of the Sea of Marmara in Mysia. The emergence of a Greek-Iranian monarchy had a strong influence on the Pontos and gave it a distinctive identity. However, the name Pontos was probably given to it externally, by the Persians or the Seleucids.

The Mithridatic dynasty, which had its roots in the northwest of Iranian Anatolia, seized power in the confused age after the conquests of Alexander the Great, who had never conquered this part of Anatolia.

Kings of the Mithridatic Dynasty

| Mithridates I Ktistes | 281 – 266 B.C. |

| Ariobarzanes | 266 – c.250 B.C. |

| Mithridates II | c.250 – c.220 B.C. |

| Mithridates III | c.220 – c.185 B.C. |

| Pharnaces I | c.185 – c.160 B.C. |

| Mithridates IV Philopator | c.160 – c.150 B.C. |

| Mithridates V Euergetes | c.150 – 120 B.C. |

| Mithridates VI Eupator | 120 – 63 B.C. |

| Pharnaces II | 63 – 47 B.C. |

| Darius and Arsaces | 39 – 37 B.C. |

Mithridates I (also Mithradates; ‘Consecrated to the god Mithras’) was the first to call himself king and would be nicknamed Ktistes, ‘founder’. His base was Paphlagonia, in the west of Pontos, but his descendants continued to add Greek ports and regions in the interior, but losing control of Paphlagonia at some point. Pontos could slowly expand because Anatolia had been allotted to the Seleucids, who never gained full control of this part of the former Achaemenid Empire. Instead, the Seleucids preferred a marriage alliance with the Mithridatic kings.

The disempowerment and killing of Mithridates VI Eupator were not the end of the Pontic kingdom, however. While the Romans were fighting their Second Civil War, between Julius Caesar and Gnaeus Pompeius (Pompey), Mithridates’ son Pharnaces II attempted to rebuild Pontic power. He had been too optimistic about his chances. Caesar, who had defeated Pompeius, immediately marched to Anatolia, joined forces with king Deiotares of Galatia, and defeated Pharnaces at Zela.

There were three kings left, belonging to a different dynasty, and ruling in the eastern part of the former Mithridatic kingdom of Pontos:

| Polemon I Eusebes | 37 – 8 BCE |

| Pythodoris | 8 BCE – 38 CE |

| Julius Polemon II | 38 – 68 CE |

In 64 B.C., and as a result of the Third Mithridatic War, Pompey officially annexed Bithynia and the western part of Pontus as the directly governed by the Roman Republic province of Bithynia et Pontus, whereas he added the larger eastern part of the previous Mithridatic kingdom (Armenia Minor, or Lesser Armenia) to the Kingdom of Galatia under the Celtic Roman client king Deiotarus as a reward for his loyalty to Rome. In 159 AD, Bithynia et Pontus became an Imperial Roman province, lasting until 295 AD.

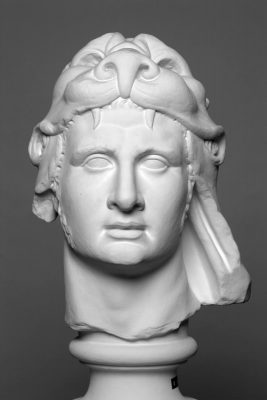

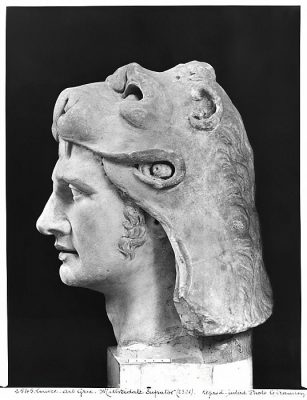

Mithridates VI Eupator (the Great)

Mithridates V was succeeded by Mithridates VI Eupator (* ca. 132 B.C. in Sinope; † 63 B.C. in Pantikapaion; reigned since 120 B.C.), who was able to conquer Colchis (more or less modern Western Georgia) and the Bosporan Kingdom (the Crimea) and expand his kingdom along the eastern and northern shores of the Black Sea. He also gained control in smaller kingdoms in post-Seleucid Anatolia (Galatia, Cappadocia) and allied himself to Bithynia and Armenia. Having expanded his power base, he embarked upon an anti-Roman policy.

Under Mithridates’ rule, Pontos became the largest and most influential kingdom of Asia Minor. The new king initially expanded his kingdom to include Greek-populated areas in and around Crimea, acting as protector against the steppe nomads. After Mithridates had thus expanded his power base around the Black Sea, he began conquests in Asia Minor. This brought him into conflict with Rome. Because of the exploitation of the Roman province Asia by the Roman tax collectors and the weakness of Rome in the civil war, there were uprisings in Asia Minor. Since Mithridates took advantage of the widespread hatred of the Romans and appeared with the promise of freedom, he met with little resistance. In a first campaign Sulla, Roman governor in Cilicia, succeeded in driving Mithridates from Cappadocia. Shortly afterwards Mithridates formed an alliance with his son-in-law Tigran II (the Great, Տիգրան Մեծ, Grk.: Τιγράνης, 140-55 B.C.) of Armenia. Thus, Mithridates VI was able to control large parts of Asia Minor, the Aegean and Greece, as well as the Bosporan (Crimean) Empire. On his order in 88 B.C., allegedly in one day, about 80,000-150,000 Italic people of Roman citizenship were killed (so-called Vespers of Ephesos).

In 89/88 B.C. the city of Ephesos passed to Mithridates. With the massacre of Ephesos the Pontic ruler intended to eliminate all Italic opposition in that region. At the same time the material expectations of his followers were to be satisfied. Although Mithridates had proclaimed himself as the liberator of the Greeks in the course of his annexationist efforts, he had not succeeded in replenishing his war chest until then. As a worthwhile target group, he identified the Italic people living in Asia Minor, who due to their origin did not adhere to his politics. In addition, these people were wealthy, as they were mainly active in trade and administration. Another reason for the massacre ordered by Mithridates is assumed to be the pent-up hatred of the population of the province Asia against the Roman tax tenants, who had exploited the province for more than 40 years.

The three Mithridatic wars lasted almost 30 years, between 90 and 65 B.C. Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (the Great) finally defeated Mithridates in 63 B.C. and subsequently put the political order in Asia Minor and Syria on a new basis. Mithridates was pushed back to the Crimea, from where he tried to intervene in Asia Minor again and again in his old age. He was finally deposed by his own family, who negotiated with Rome, in favor of his son.

Mithridates VI is also known for his newly developed alloys in coinage, his multilingualism, and his knowledge of botany and pharmacology. He is said to have ruled the 22 peoples he controlled in their respective languages. Ethnic and cultural diversity can also be found in the composition of his royal court: two thirds of the Pontic court are said to have consisted of Greeks from various countries of origin. With Romans, Cappadocians and Thracians, the result is a picture of an international and multicultural court with Greek influence.

Mithridates studied botany and pharmacology throughout his life. Even today the species hemp agrimony (bot. Eupatorium cannabinum) is named after him. Fearing that his mother might poison him the same way she had poisoned his father, Mithridates developed a complex remedy consisting of 54 ingredients that immunizes against poisoning when taken daily. The king’s knowledge of the universal antidote against poisons, called Mithridaticum, or Mithridate, and the development of a therapy which aims at immunization by a constant intake of small doses of poisons (Mithridatization ) became famous. It is handed down that Mithridates VI was one of the first to create a botanical garden. According to Pliny the Elder Mithridates wrote a book about poisons.

Under Roman and Byzantine Rule

With the subjection of the Mithridatic kingdom by Pompey in 64 BC, the western part of the previous Pontic kingdom was annexed to Bithynia, forming the double province Pontus and Bithynia. This province included only the seaboard between Heraclea (today Ereğli) and Amisus (Samsun), the ora Pontica. The larger part of Pontus, however, was included in the province of Galatia.

Hereafter the name Pontus without additional qualification was regularly employed to denote the eastern half of the province Bithynia et Pontus. The eastern part of the previous Mithridatic kingdom was administered as a client kingdom together with Colchis. Its last king was Iulius or Markus Antonius Polemon II of Cilica (11/12 B.C.-68 A.D.), son of the Pontic queen Antonia Tryphaina, as granddaughter of the Roman commander Markus Antonius an influential personality in the eastern Mediterranean at her time. From 17 to 38 A.D., mother Tryphaina and son Polemon jointly administered the Pontos.

With the reorganization of the provincial system under emperor Diocletian (about 295 A.D.), the Pontic districts were divided up between three smaller, independent provinces within the Dioecesis Pontica:

- Galatian Pontus, also called Diospontus, later renamed Helenopontus by Constantine the Great after his mother Helena. It had its capital at Amisus, and included the cities of Sinope, Amasia, Andres, Ibora, and Zela as well.

- Pontus Polemoniacus, with its capital at Polemonium (previously Fanizan; also called Side; today: Fatsa), and including the cities of Neocaesarea, Argyroupolis, Comana, and Cerasus as well.

- Cappadocian Pontus, with its capital at Trebizond, and including the small ports of Athanae and Rhizaeon. This province extended all the way to Colchis.

Byzantine province and theme

The Byzantine Emperor Justinian I further reorganized the area in 536:

- Pontus Polemoniacus was dissolved, with the western part (Polemonium and Neocaesarea) going to Helenopontus, Comana going to the new province of Armenia II, and the rest (Trebizond and Cerasus) joining the new province of Armenia I Magna with its capital at Justinianopolis.

- Helenopontus gained Polemonium and Neocaesarea, and lost Zela to Armenia II. The provincial governor was relegated to the rank of moderator.

- Paphlagonia absorbed Honorias and was put under a praetor.

By the time of the early Byzantine Empire, Trebizond became a center of culture and scientific learning. In the 7th century, Tychicos of Byzantium returned from Constantinople to establish a school of learning. One of his students was the early Armenian geographer, natural philosopher and polymath Anania of Shirak (Անանիա Շիրակացի; 610-685),who spent eight years at Tychicos’ college.

Under the Byzantine rule, the Pontus came under the Armeniac Theme, with the westernmost parts (Paphlagonia) belonging to the Bucellarian Theme. Progressively, these large early administrative units were sub-divided into smaller ones. By the late 10th century, the Pontus consisted of the two themes of Chaldia (Greek: θέμα Χαλδίας; established by 840), which was governed by the Gabras family, and Koloneia (Greek: θέμα Κολωνείας), which originally was part of the Armeniac Theme. During the Late Middle Ages, the Theme Chaldia formed the core of the Empire of Trebizond until its fall to the Ottoman Empire in 1461. After the 8th century, the area experienced a period of prosperity which was brought to an end only by the Seljuk conquest of Asia Minor in the 1070s and 1080s. Restored to the Byzantine Empire by Alexios I Komnenos, the area was governed effectively by semi-autonomous rulers, like the Gabrades of Trebizond.

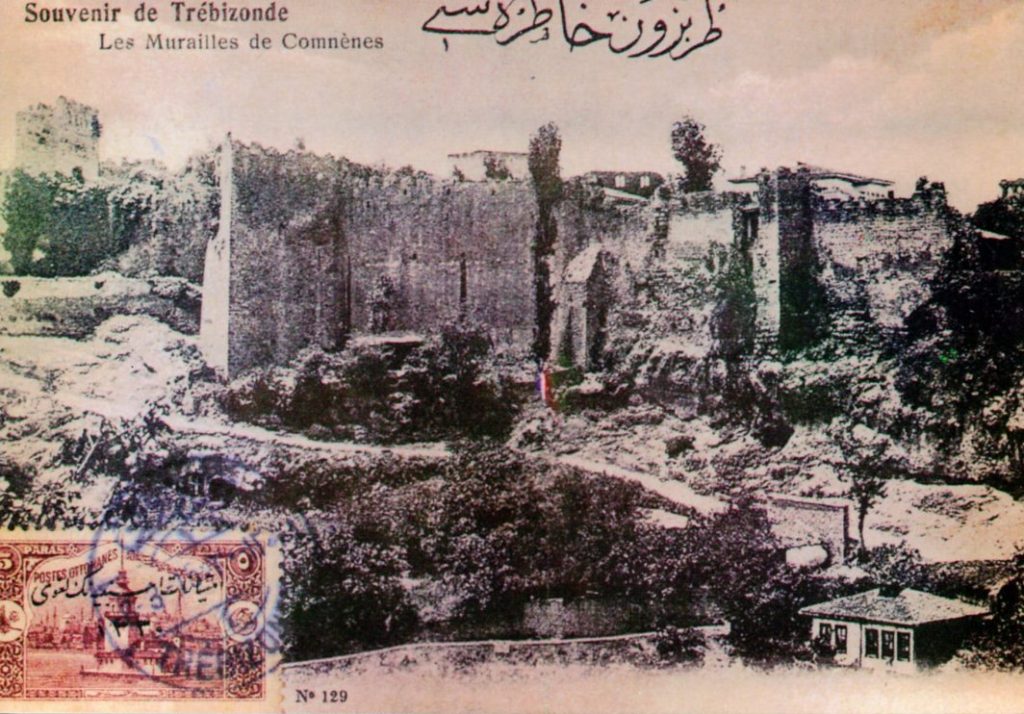

The region was secured militarily from the 11th through the 15th centuries with a vast network of sophisticated coastal fortresses.

Tychicos of Byzantium: Founder of the Trebizond Center of Higher Learning in the Seventh Century

Next to Alexandria, Edessa (Urfa) and other cities, Trebizond became an “important centre of higher learning during the early Seventh Century, largely because of the reputation of Tychicus of Byzantium as one of the foremost thinkers and teachers of his day. Widely travelled, Tychicus had studied in Jerusalem, Alexandria, Rome, Constantinople and Athens (where he had studied philosophy for several years) before settling in Trebizond. Invited back to Constantinople to a professorship, he refused and, with the advantage of a substantial library, made Trebizond a teaching magnet. One Armenian, Ananias of Shirak (or Shirakatsi) has left a telling account of his own quest for knowledge which gives us an insight into Seventh Century Armenian learning. As a young man, Ananias, despairing of finding respect for knowledge among the Armenians, set out to travel around Greek centres of learing, seeking out mentors. First, at Theodoupolis, he found Eliazar, but soon exhausted what he could be taught by him. He was directed next to Christodoulos, who lived in the Fourth District of Armenia, and spent six months with him being taught mathematics. Making his way to Constantinople, he met Pelagrius, a deacon of the patriarch, who was about to set out with numerous acolytes to study under Tychicus at Trebizond. Ananias joined this party and went on to spend several years studying under Tychicus, marvelling at the fluency with which he translated into Armenian and being introduced ‘to many writings that were not translated into our tongue’.”

Quoted from: Lowe, Roy; Yasuhara, Yoshihito: The Origins of Higher Learning: Knowledge networks and the early development of universities. London, New York: Routledge, 2017, p. 28

The Empire of Trebizond (1204-1461)

Chrysobull of Dionysiou Monastery on Mount Athos (1374; source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Chrysobull_of_Alexius_III_of_Trebizond.jpg)

The Empire of Trebizond was one of three successor rump states of the Byzantine Empire that flourished during the 13th through 15th. The empire was formed in 1204 with the help of the Georgian queen Tamar (the Great) after the Georgian expedition in Chaldia and Paphlagonia, commanded by Alexios Komnenos a few weeks before the Sack of Constantinople. Alexios later declared himself Emperor and established himself in Trebizond (modern day Trabzon, Turkey). Alexios and David Komnenos, grandsons and last male descendants of deposed Emperor Andronikos I Komnenos, pressed their claims as Roman Emperors against Byzantine Emperor Alexios V Doukas. However, the later Byzantine emperors, as well as Byzantine authors, such as George Pachymeres, Nicephorus Gregoras and to some extent Trapezuntines such as John Lazaropoulos and Basilios Bessarion, regarded the emperors of Trebizond as the ‘princes of the Lazes’, whose possession was misledingly termed Lazica, or ‘Principality of the Lazes’. Thus from the point of view of the Byzantine writers connected with the Laskaris and later with the Palaiologos dynasties, the rulers of Trebizond were not emperors.

After the crusaders of the Fourth Crusade overthrew Alexios V and established a Latin Empire, the Empire of Trebizond became one of three Byzantine successor states to claim the imperial throne, alongside the Empire of Nicaea under the Laskaris family.

Due to its natural harbors, defensible topography and access to silver and copper mines, Trebizond became the pre-eminent Greek colony on the eastern Black Sea shore soon after its founding. The Pontic Alps served as a barrier first to Seljuk Turks and later to Turkoman marauders.

The empire traces its foundation to April 1204, when Alexios Komnenos and his brother David took advantage of the preoccupation of the central Byzantine government with the encampment of the soldiers of the Fourth Crusade outside their walls (June 1203 – mid-April 1204) and seized the city of Trebizond and the surrounding province of Chaldia with troops provided by their relative, Tamar of Georgia. Henceforth, the links between Trebizond and Georgia remained close, but their nature and extent have been disputed. However some scholars believe that the new state was subject to Georgia, at least in the first years of its existence, at the beginning of the 13th century.

The rulers of Trebizond called themselves Megas Komnenos (‘Great Comnenus’) and initially claimed supremacy as ‘Emperor and Autocrat of the Romans’. However, after Michael VIII Palaiologos of Nicaea recaptured Constantinople in 1261, the Komnenian use of the style ‘Emperor’ became a sore point. In 1282, John II Komnenos stripped off his imperial regalia before the walls of Constantinople before entering to marry Michael’s daughter, accepting his legal title of despot. However, his successors used a version of his title, ‘Emperor and Autocrat of the entire East, of the Iberians and the Perateia’ until the Empire’s end in 1461.

Following the death of Alexios II (1297–1330), Trebizond suffered a period of repeated imperial depositions and assassinations. Two groups struggled for ascendency: the Scholaroi, who have been identified as being pro-Byzantine, and the Amytzantarantes, who represented the interests of the native aristocrats (archontes). The years 1347-1348 marked the apex of this lawless period. The Turks took advantage of the weakness of the empire, conquering Oinaion (Ünye) and besieging Trebizond, while the Genoese seized Kerasus (Giresun). Under the rule of Alexios III (reigned 1349–1390), Trebizond was considered an important trade center and was renowned for its great wealth and artistic accomplishment. It was at this point that their famous diplomatic strategy of marrying the princesses of the Grand Komnenos to neighboring Turkish dynasts began.

The Trapezuntine monarchy would survive the longest among the Byzantine successor. The small Empire of Trebizond, which had prospered from maritime trade, was able to survive the fall of Constantinople for another eight years under the protection of the Pontic mountains, but on 15 August 1461 it fell into the hands of the Ottoman conqueror Mehmet II as the last still Christian state of Asia Minor states (the Crimean Principality of Theodoro, an offshoot of Trebizond, lasted even another 14 years, falling to the Ottomans in 1475). Sultan Mehmet banished the last Pontic emperor, David Megas Komnenos, to Adrianoupolis (Thrace), but ordered him to return to Constantinople after two years and to renounce his faith. When David refused, the Sultan had him and David’s three sons decapitated and their bodies thrown to the dogs outside the walls of Constantinople.

Not all Christian nobles possessed the strength of faith and martyrdom of the last Comnenes. Those who could not or did not want to flee after the Ottoman conquest, preserved their privileges and their property only if they accepted Islam. Especially in the 17th century, numerous Georgian, Laz and Pontos Greek aristocrats, together with their serf peasants, converted to Islam.

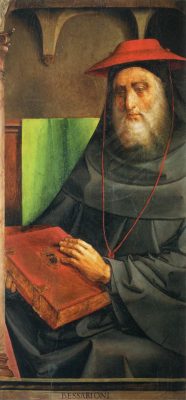

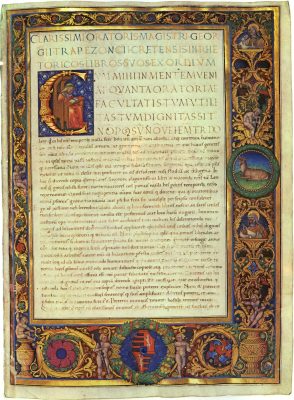

Basileios or Bessarion: “Inter graecos latinissimus, inter latinos graecissimus”

Appreciation

The later cardinal and Latin titular patriarch of Constantinople (1463-1472) Bessarion (monk’s name) was born as Basileios in late 1399 or early 1400 in Trapezounta (Trebizond; Trabzon) and died on 18 November 1472 in Ravenna. He went down in the Church or humanities history as a theologist of unification and a humanist, in particular as a propagator of Plato’s teachings for the western world, rediscovered by his teacher Phleton. Among Bessarion’s numerous theological and philosophical writings are to be mentioned especially the four books of his defensive writing In calumniatorem Platonis (1454; in Latin 1469), written first in Greek, with which Bessarion wanted to put the (neo)Platonic philosophy into the service of the Christian faith.

Bessarion is not only regarded as an altruistic promoter of the idea of church unity, but also as one of the leading scholars of the 15th century. His residence in Rome was a real centre of humanistic scholarship (‘Academy’). The Italian humanist Lorenzo Valla described his patron Bessarion as “the greatest Latin among the Greeks and the greatest Greek among the Latins”.

Praise on Trapezounta / Trebizond

Among the early works of Bessarion is his Greek eulogy Eis Trapezounta to his home town. It offers a detailed, historically and geographically valuable description of the glorified city including the suburbs and the imperial palace on the Acropolis. In contrast to many other cities, Trapezounta is not in decline, but is becoming more and more beautiful. Thanks to its excellent port, the best on the Euxine, the city is an outstanding center of long-distance commerce and craftsmanship is flourishing. Further advantages are the pleasant climate, the fertile soil and the abundance of wood, which is important for ship and house building. The history of the city is dealt with in detail, including the prehistory of its foundation. Bessarion emphasizes that Trapezounta was never conquered by enemies.

Education and life

Bessarion came from simple circumstances. At first, he attended the public school in Trebizond, where his talent was noticed. Then his parents handed him over to the Metropolitan Dositheos of Trebizond to give him a good education. When Dositheos had to leave his metropolitan seat in 1416/17 due to a conflict with the Emperor of Trebizond and went to Constantinople, he took his protégé with him. In the capital of the Byzantine Empire there was no university in the Western sense; secular and spiritual education was in the hands of a cleric, the ‘universal teacher’ (katholikós didáskalos). This office was held by the scholar John Chortasmenos (d. 1431/7). He taught the young Basileios in the school subjects known in the West as the ‘Seven Liberal Arts’ and in ‘Philosophy’, which was understood as Aristotelian logic. These were the fields of knowledge known to the Byzantines as ‘Hellenic’, the knowledge of which made up the ‘pagan’ general education based on the pre-Christian ancient school system (mathḗmata). In addition, there was instruction in the dogmatics of orthodox theology. This was in the early 15th century coined by Palamism, a contemplative orientated direction, which declared the ‘Hellenic’ education, in particular philosophy, to be useless. From it a conflict arose for students eager for education, which Basileios solved for himself in the sense of an affirmation of the pre-Christian antique culture.

Basileios changed his name to Bessarion when he became a monk in 1423. In 1425 he was ordained a deacon, in 1430 a priest. After his emigration to the Peloponnese (ca. 1431) Bessarion was a student of the philosopher Georgios Gemistos (pseudonym: Plethon; *c. 1355/1360 in Constantinople; † 26 June 1452 or 1454 in Mystras) in Mystra (near ancient Sparta), who taught him philosophy and mathematics. Around 1436, Emperor John VIII appointed Bessarion Abbot of the Basileus Monastery in Constantinople and elevated him to the Metropolitan Throne of Nicaia on 11 November 1437 (hence the common epithet of Cardinal Nicenus).

Pursuing his ecclesiastical career, Bessarion engaged in diplomatic activity in the service of the Byzantine emperor. This put him in contact with the court of the Despot of Mystra. The decisive year in the life of Bessarion was probably 1437, when he was made metropolitan of Nicea and left for Italy as member of the Greek delegation to the Council of Ferrara-Florence (1438/9).

The Council was mainly devoted to an attempt at unifying the Latin and Greek Churches, which the Western European powers had made a condition for providing military support to Palaiologos as he attempted to fend off the Ottoman Turks. As a member of the Greek delegation, the young Bessarion was not eager to concede the main dogmatic point of disagreement between the two churches, which had led to their separation in the eleventh century: the problem of the place of the Holy Spirit in the Creed. According to the Greeks the Spirit proceeded only from the Father, while in the Roman formulation it also proceeded from the Son (Filioque). And yet, driven by his concern for the unstable political situation in Greece and finally convinced by the texts of the Church Fathers, Bessarion changed his mind and in April 1439 pronounced an oration (the Oratio dogmatica de unione) and, after some initial hesitation, became the spokesman for the supporters of an unification of the churches, in which he advocated for agreement between Greek and Latin authors. In July 1439 Bessarion read the act of union between the Roman and the Greek Church in Florence. The same year, while he was in Greece for the last time, Bessarion was made Cardinal.

Appointed Cardinal Presbyter of Santi XII Apostoli on 18 December 1439 by Pope Eugen IV, Bessarion returned in 1440 for a short time to Constantinople, to settle down finally in Italy. Appointed Cardinal Bishop of Sabina by Nicholas V on March 5, 1449, and Cardinal Bishop of Tusculum on April 23, 1449, and successfully active in Bologna as an apostolic legate from 1450 on, all his energy was devoted to the liberation of his homeland and the proclamation of a crusade against the Turks after the fall of Constantinople in 1453. However, Pius II’s efforts at the Congress of Mantua (1459) and Bessarion’s legation to Germany (1460- 1461) failed.

On a legation to Venice Bessarion, who was raised to the Latin Patriarch of Constantinople in May 1463 after the death of Isidoros of Kiev, was able to persuade the Doge to declare war on the Ottomans, but the enterprise was dissolved again by the death of Pius II (15 August 1464). Under his successor Paul II Bessarion cultivated above all his humanistic endeavours.

Bessarion would spend the rest of his life as one of the most important and influential members of the Roman Curia. He took particular care of Greek rites abbeys, like those in Calabria, Messina, and Grottaferrata. He obtained a number of benefices, and in 1458 he was selected as protector of the Franciscan Order. In 1463 he also became Patriarch of Constantinople. He even came close to being elevated to the papacy at least twice, but apparently his beard—which for many symbolized his Greek origins—prevented him from garnering the necessary support. His activities as a cardinal were coupled with scholarly enterprises, which he undertook personally, and also sponsored as the patron of a circle of intellectuals who were in many cases Greek emigrés like him. Men like Theodoros Gazis(d. 1476) and Niccolò Perotti (d. 1480)—and for a short period even his nemesis-to-be George of Trebizond (d. 1473 or 1484)—were all part of the Cardinal’s entourage.

After the fall of Constantinople in 1453, Bessarion’s main interest was in rescuing the cultural heritage of his homeland, Greece, and he pursued this goal on both intellectual and political planes. From an intellectual point of view, Bessarion’s plan involved salvaging Greek texts which were until then unknown in Western Christendom and were generally rare (to the extent that in some cases they survive today only in the exemplars collected by the Cardinal). An avid lifelong book collector, Bessarion assembled a library in order to prevent the loss of these treasures: “without books, the tomb would cover the names of men, just as it covers their bodies”. Bessarion feared—indeed he was consumed with terror—“lest all those wonderful books, the product of so much toil and study by the greatest human minds, those very beacons of the earth, should be brought to danger and destruction in an instant”. Bessarion felt that Venice—a city with which he had entertained a long relationship and where he served as papal legate in 1463—could be a safe haven for his library and the important collection of manuscripts he donated to the church of San Marco (Venice) around 1468 formed the first nucleus of the Biblioteca Marciana.

In addition to saving books from destruction, Bessarion had also a more practical political agenda for his homeland; he was among the most vocal advocates for the call for a new crusade to free Greece from Ottoman control. He was therefore engaged in several diplomatic missions, in Germany and then in Vienna, which aimed to convince Western rulers to fight the Turks. After an attempt in 1464 failed because of the death of Pope Pius II in Ancona, Bessarion worked until the end of his days to build support for a project that appeared more and more illusory with every passing year.

Pope Sixtus IV once again sent Bessarion on a diplomatic mission to France to persuade King Louis XI to join a crusade against the Turks (summer/autumn 1472). Returning home seriously ill from the failed legation, the aged cardinal died in Ravenna in November 1472. He was interred in his titular Church, Santi Apostoli in Rome, where the prominent Italian painters Antoniazzo Romano and Melozzo da Forlì had decorated a chapel in his name between 1464 and 1467.

Sources:

- Basil [Cardinal] Bessarion. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosphy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/bessarion/

- Encyclopaedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Bessarion

- Biographisches Lexikon zur Geschichte Südosteuropas: https://www.biolex.ios-regensburg.de/BioLexViewview.php?ID=566

Georgios Trapezountios and Bessarion: The Dispute over Neo-Platonism

Although born in then Venetian ruled Crete, the Greek philosopher Georgios (Gr.: Γεώργιος Τραπεζούντιος, Latin Georgius Trapezountius; George of Trebizond; * 4. April 1395 in Candia, Crete; † 1473 or 1484 in Rome) chose the surname Trapezountios, as his family came from Trebizond. Along with Bessarion, he is considered one of the revivalists of classical Greek literature in Italy and became known as a pugnacious advocate of Aristotle’s philosophy and as a translator of Greek authors. The two central Latin works of the Plato-Aristotle Controversy of the Fifteenth Century were George of Trebizond’s Comparatio Philosophorum Platonis et Aristotelis (1458) and Bessarion’s In Calumniatorem Platonis (Against Plato’s slanderer) in response to George. “With this, Georgios Trapezuntios and Bessarion continued the debate about which of the two ancient Greek philosophers should be given priority. This debate runs (…) like a red thread through the history of Byzantine philosophy.”[7]

Pope Nicholas V entrusted Georgios Trapezountios with the translation into Latin of the Greek writings of Eusebios, Cyril, Chrysostom, Aristotle (Rhetoric), Plato (1451, Laws) and Ptolemy. Trapezountios made word-to-word translations, which at that time were already sharply criticized by humanists, and came into conflict with Bessarion, with Theodoros Gazis, Niccolò Perotti and Poggio. Because of the slovenliness of his work and his presumptuous nature, he forfeited papal favour and had to leave Rome in 1452.

On a trip to Byzantium, Trapezountios probably also made the miserably failed attempt to convert the Ottoman Sultan to Christianity. In his book The Truth of the Christian Faith he is convinced that God desires the ‘unity of all people’, and suggested to the Sultan to renounce violence and to convene a conference of Christians and Muslims.

But Trapezountios’ dispute with Bessarion for and against Plato, which inspired Bessarion to his polemic, only developed after Trapezountios had finally separated from the circle around Bessarion in the 1450s.

The discussion reached its preliminary climax in 1458 with the publication of Trapezountios’ treatise Comparatio philosophorum Platonis et Aristotelis. In this writing he subsumed all common views on Platonic philosophy and conveyed many common prejudices against the Platonists. In the first book he compared Plato with Aristotle in terms of education and in the second book in terms of the compatibility of both philosophical views with Christian teaching. In the course of his argumentation, he made a series of damning judgments both about Plato as a person, whom he rebuked for his voluptas and depravitas (keyword: homosexuality), and about his philosophy, which in his opinion was incompatible with Christian doctrine. Finally, in the third and last book, Georgios was a prophet, a ‘cryer in the desert’, whose duty it was to warn the whole of Western civilization of the dark dangers that, in his eyes, the spread of Plato’s teachings threatened.[8]

For “until the beginning of the thirties of the 15th century Georgios Trapezountios was an admirer of Plato, whom he had praised as the highest teacher of philosophy (summus philosophie magister) as late as 1426. His turning away from Plato began when he was confronted with his criticism of the great Attic statesmen of the 5th century B.C. (Miltiades, Themistocles, Kimon and Pericles) and of the Rhetoric. His conversion to Roman Catholicism (early 1426) and his service to the Roman Curia made him familiar with

the scholastic theology of the Western Church, dominated by Aristotle. Therefore, the fact that the theology of the Greek Orthodox Church of Byzantium was strongly influenced by Plato seemed to him to be a serious obstacle to the unification of the churches. Islam, which under the leadership of the Ottomans threatened Constantinople (until 1453) and Europe, was also regarded as influenced by Plato. Above all, however, he held Plato’s influence responsible for the new paganism of the Georgios Gemistos Plethon, whom he had met at the Union Council of Ferrara/Florence. Above all, however, he held Plato’s influence responsible for the new paganism of the Georgios Gemistos Plethon, whom he had met at the Union Council of Ferrara/Florence. Over the years Trapezountios believed more and more in a real conspiracy of Platonists to reawaken paganism. Possibly he even suspected Bessarion, because he was a student of Plethon, of being involved in this conspiracy. Since the new paganism influenced by Plato increasingly seemed to him to be a threat, he wanted to warn the Occidentals of this danger and therefore wrote a 1458 published paper with the title Comparatio Philosophorum Aristotelis et Platonis in 1457, in which he tried to prove the superiority of Aristotle over Plato. Trapezountios claimed that Plato and his followers covered up the lack of accuracy and logical coherence of their thinking with enigmatic formulations and wordy language. Only Aristotle managed to create logic. According to Trapezountios, only Aristotle’s teaching is in agreement with that of the Roman Catholic Church. He claims to have already found the Christian doctrine of the Trinity in his writings on heaven. Of course, he finds it difficult to harmonize Aristotle’s ́ doctrine of the eternity of the world with the Christian faith in creation. In this connection he asserts that Aristotle distinguishes between the eternity of the world and the eternity of God as the supreme principle and the first mover of the world, that is to say, Aristotle ascribes to God only an everlasting presence in the actual sense. While Aristotle’s doctrine of the soul is also in complete agreement with the church’s doctrine, Plato taught the pre-existence of the soul. In general, all Christian heresies from Origenes and Arius up to the Palamites of the Eastern Church can be traced back to Plato, whereas the occupation with Aristotle, especially in the Occident, created the most outstanding achievements of Christian theology.”

Quoted from: Todt, Klaus-Peter (Mainz): In Calumniatorem Platonis: Cardinal Johannes Bessarion (ca. 1403-1472) as mediator and defender of Plato’s philosophy. http://www.europa-zentrum-wuerzburg.de/unterseiten/Band12-Todt.pdf

Pontiaká and Romey(i)ka: The Pontic Greek dialect

The term ‘Byzantine Empire’ coined by Hieronymus Wolf as late as the 16th century, was unknown to the citizens of the (Eastern) Roman Empire. The term ‘rum (Plural: rumlar)’, still common in Turkey, refers to the descendants of the Eastern Roman Empire. It can be derived from their self-designation: ancient Greek Ῥωμαῖοι (modern Greek Ρωμαίοι) – Rōmaioi (‘Romans’). Speakers of Pontic Greek thus refer to their language as Romey(i)ka (‘Roman’) or Pontiaká (‘Pontic’). It was and is written with Greek (with the diacritics σ̌ ζ̌ ξ̌ ψ̌ for /ʃ ʒ kʃ pʃ/, α̈ ο̈ for [æ ø]), Latin or Cyrillic letters.

Language or Greek dialect?

The linguistic, lexical and grammatical features of Pontic Greek are so pronounced that Pontiaka or Romey(i)ka almost seems to be a language in its own right. It is hardly understood not only by Greeks in Greece today. Greeks from other regions of Asia Minor also had difficulties with it (cf. the quotation from Elias Venezis’ memoirs recorded close to events). The reasons for these difficulties of understanding lie in the geographical isolation of Pontos, where the Attic-Koiné Greek of the Greek colonists developed separately from the rest of the Greek language for almost two millennia; it thus preserved elements of Ancient Greek that are no longer found in today’s standard Greek.

At the same time, Pontic Greek was exposed to numerous influences from neighbouring cultures and changing systems of rule: Iranian (Persian, Parthian), South Caucasian (Laz) languages, Armenian, as well as Byzantine Greek and Ottoman Turkish.

Sub-dialects and historic distribution

Similar to most modern Greek dialects, Pontic Greek is mainly derived from Koiné Greek, which was spoken in the Hellenistic and Roman times between the 4th century B.C. and the 4th century AD. Following the Seljuk invasion of Asia Minor during the 11th century AD, Pontos became isolated from many of the regions of the Byzantine Empire.

The Greek linguist Manolis Triantafyllidis (1883-1959) distinguishes between a western group of Pontos Greek (Oinuntian or Niotic, around Oinoe (Turkish: Ünye), an eastern coastal group ( Trapezuntian, around Trabzon), and Chaldian, which was spoken in the eastern hinterland (around Gümüşhane); most speakers lived in Chaldia.

Ophitic/Romeyka

The inhabitants of the Of valley who had converted to Islam in the 17th century remained in Turkey after the forcible population ‘exchange’ of 1923 and have partly retained the Pontic language until today. Their dialect, which forms part of the Trapezountiac subgroup, is called ‘Ophitic’ by linguists, but speakers generally call it Romeyka. As few as 5,000 people are reported to speak it. There are however estimates that show the real number of the speakers as considerably higher. Speakers of Ophitic/Romeyka are concentrated in the eastern districts of Trabzon province: Çaykara (Katohor), Dernekpazarı (Kondu), Sürmene (Sourmena) and Köprübaşı (Göneşera). Although less widespread, it is still spoken in some remote villages of the Of district itself. It is also spoken in the western İkizdere (Dipotamos) district of Rize province. Historically the dialect was spoken in a wider area, stretching further east to the port town of Athina (Pazar).

Ophitic has retained the infinitive, which is present in Ancient Greek but has been lost in other variants of Modern Greek; it has therefore been characterized as ‘archaic’ or conservative (even in comparison with other Pontic dialects) and as the living language that is closest to Ancient Greek.

A very similar dialect is spoken by descendants of Christians from the Of valley (especially from Kondu) now living in Greece in the village of Nea Trapezounta, Pieria, Central Macedonia, with about 400 speakers.

Ioanna Sitaridou, a linguist of Pontic Greek descent, calls the Pontic Greek dialect, which is still spoken by about 5,000 people in the Trabzon area, Romeyka. In its sentence structures as well as in many vocabulary, this language, which is spoken by Islamicized Greeks, has been able to preserve its archaic elements most strongly, since its speakers separated themselves from the Christian Pontic Greeks and were no longer exposed to the influences of the liturgical language due to their change of faith.

Due to the forced resettlement of the Christian Pontic Greeks in accordance with the Lausanne Treaty (1923), speakers of Pontic Greek were brought to the Republic of Greece, where their children were not taught Pontic Greek in schools, but Standard Greek. Many second and third generation Pontians who grew up in Greece also remember with pain and anger how they were discriminated against and ridiculed for their dialect by Greek school teachers and non-Pontic classmates.

Though Pontic was originally spoken on the southern shores of the Black Sea, from the 18th and 19th century and on substantial numbers migrated into the northern and eastern shores, into the Russian Empire. Pontic is still spoken by large numbers of people in Ukraine, mainly in Mariupol, but also in other parts of Ukraine such as the Odessa and Donetsk region, in Russia (around Stavropol) and Georgia. The language enjoyed some use as a literary medium in the 1930s. Among other things, a school grammar was written down (Konstantinos Topkharas, 1998 [1932]), which explains Pontic grammar in Pontic language. In these areas, Pontic Greek is considered the most vital today, although large parts of the speaker populations migrate to Greece.

Outside Turkey and Greece one can distinguish the following sub-dialects:

- the Northern group (Mariupol Greek or Rumeíka), originally spoken in Crimea, but now principally in Mariupol, where the majority of Crimean Pontic Greeks of the Rumaiic subgroup now live. Other Pontic Greeks speak Crimean Tatar as their mother tongue, and are classified as “Urums“. There are approximately half a dozen dialects of Crimean (Mariupolitan) Pontic Greek spoken.

- Soviet Rumaiic, a Soviet variant of the Pontic Greek language spoken by the Pontic Greek population of the Soviet Union.

Today’s distribution

The number of speakers of Pontic Greek has been estimated at 300,000-778,000 for the period around 2015, of which about 400,000 are located in Greece (where Pontiaka and Rumeyika have no official status).

In 1989, 40,000 speakers lived in Russia, including 15,000 each in the Krasnodar region and near Stavropol. In Georgia, 60,000 speakers were reported at that time, and 2,500 speakers lived in Armenia. The Pontic Greek dialects in the Georgian Tsalka and the Armenian Alaverdi regions were partly derived from Greek dialects of Cappadocia, which were presumably assimilated from Pontic Greek.

Endangered language

In its latest edition of the Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger (2010; updated 2017), UNESCO estimates the number of speakers of Pontic Greek at 300,000, with Armenia, Georgia, Greece, the Russian Federation, Turkey and Ukraine as the distribution areas. It classifies Pontic Greek as a language definitely threatened with extinction because the speakers (according to this classification by UNESCO), with the exception of a few half speakers and linguists, are only older speakers and there is no transmission of the language to the younger generation.

In Greece, the youth of Pontic origin often speak standard Greek as their first language. The use of Pontic has been maintained more by speakers in North America than it has in Greece.

Literature and music

Pontic Greek has a rich oral tradition. The Pontic Greek songs, also referred to as ‘Pontiaká’, are particularly popular in Greece and among the local Pontic community. There is also some limited production of modern literature in Pontiaka, including poetry collections (among the most renowned writers is Kostas Diamantidis), novels, and translated Asterix comic albums.

Wikipedia in Pontic Greek – Η Βικιπαίδεια σα Ποντιακά τα Ρωμαίικα τη Πόντονος

Elias Venezis: “Very funny was their Greek”

At the age of just 18, the later Greek novelist Elias Venezis (Gr.: Ηλίας Βενέζης; i. e. Elias Mellos; March 4, 1904 – August 3, 1973) was deported by the Kemalist rulers to a concentration camp for Greek forced laborers (of Ottoman nationality). He published his memoirs of this time event-close under the title Number 31328 (Το Νούμερο 31328; 1924; 1931). In the 15th chapter of this autobiographical work, Venezis (who himself came from the Ionian city Ayvalık (Gr.: Kydonies)) describes the arrival of Pontic Greek forced laborers in this camp. At the same time, his description hints at the pronounced regionalism and the pecularities of the Pontic Greeks:

“While this affliction united us ever more closely, a group of companions stood apart, the Ambrosians and Pegasians, about fifty men. They were brought from the Ankara work battalion.They were Greeks from the Sivas area, down near Trapezunt. They’d been working 3 or 4 years longer than us in the work battalions. The Hellenic army had not penetrated into their area. But the Turks had drafted them and used them for stone cutting. They differed from us in that they wore costumes that had not been taken from them. It was a kind of harsher dress; the pants first bulge out a little and then close tightly around the calves. In the good times, these people roamed all over Anatolia. ‘Cotton pads we fix, quilts we mend’. And when they weren’t pounding stones, they’d turn the spindle from dawn till dusk. Even on the road, when we went to forced labor, they wouldn’t let the spindle rest. Most of them had names like Ambrosios or Pegasios.

Very funny was their Greek. They could not suppress the voiced n, always put the verb at the end as in the Turkish syntax and mixed Greek with Turkish words.

They all slept in the same accommodation, did not separate from each other, did not mix between us. If one of them stepped out of line and was late to join them, they would all step outside the door together and call out. Then they went around the other shelters and asked:

Have you seen the Pegasios? Have you seen the Ambrosios?

Some jokers from Smyrna, from among our own, held them up. Then, for a brief while, there was a merriment.”

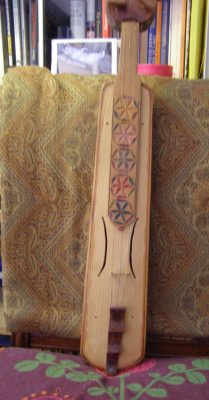

Ποντιακή λύρα – Pontiaki Lyra – The Pontic Fiddle (Gr.: Kementsé; Tr.: Kemençe)

The string instrument lyre is a Greek invention. From ancient Greek mythology we learn that the god Hermes made the first lyre: from animal armor and three branches which he stretched into “sweet sounding strings”.

The lyre went through several stages of development during its 5,000-year history. Its first name was Phyrminx. Probably the 4-string Phyrminx was called Lyra of Hermes. The following changes to the lyre involved increasing the number of strings and modifications to the shape of the sounding body. From the 10th to the 15th century A.D. this instrument was called fiddle in Europe. In the 15th century AD the name ‘lyre’ reappeared. A family of lyras of different size, shape and number of strings was created. One of these lyras was the lyra da braccio. After its perfection by Italian artists it was called violin.

The Lyra in the Pontos

However, the Black Sea Greeks simplified the instrument again, and this variant was called the Pontic lyra. An even earlier emergence of the simple Pontic lyra, for example at the time of the development of the ‘fiddle’, cannot be completely ruled out. The Greek Pontians called the 3-string lyra Kementsés and the 8-string Kemanés. The kemanés has five strings at the top and three below these five. The bow plays only the five upper strings and thus makes the lower ones vibrate. The reasons for the equation of lyra and kementsés are probably the same number of strings and the same way of playing them and holding the bow. But also the mixture of languages caused by the contacts between Greek Pontians and the Ottoman people may have played a role. The fact that in Pontic tradition one and the same person plays the lyre, sings and dances clearly shows the influences of musical customs in ancient Greece.

The Kementsés with its elongated shape, on the other hand, is adapted to the Anatolian way of playing, in which the player sits and crosses his legs. The shape of this instrument excludes playing in an upright position, as is typical for the Pontic lyre. It is without doubt the musical instrument that defines Pontic culture, and has a very distinct melody unlike any other instrument, used in Pontos. It has significant symbolic value for Pontic Greeks and serves as a symbol of their cultural identity.

The Pontic lyra comprises a narrow box shaped body which includes a neck and a pegbox, and a soundboard which covers the body. The body is either made by hollowing out a single piece of wood, or by gluing pieces together. The best lyra are said to be made of extremely dense wood such as cherry, plum, mulberry, walnut or juniper wood. Cedar is sometimes used. The soundboard is made of pine or spruce.

The sides of the body are generally 2-3mm in thickness, as is the soundboard. The pegs are made of hardwood (usually the same wood as the body) and are inserted from the front. Until around 1920, some, or all of the three strings were made of silk. However, silk strings produce a beautiful but weak sound. Silk made way for gut strings and subsequently replaced by metal strings.

Traditionally, the bow (doksar) was made from an olive branch however nowadays it’s made from any light piece of wood. Hair from a male horse’s tail was used historically. Nowadays bows with synthetic hair are more commonly used. While playing, the tension of the bow hair is controlled by the second and third finger while it is held palm upwards.

The instrument can be played while standing up or sitting down and is held vertically. When seated, the bottom of the lyra is rested between the thighs of the player. The chords are touched with the flesh of the fingers, not the nails. There is no vibrato. A particular characteristic of the Pontic lyra is its polyphony in which drone effects and parallel fourths dominate. Wrist movement is also used especially in faster paced tunes.

Two classes of kementsés (kemenche) differing in size have been distinguished, but local Black Sea Turks did not differentiate them. The smaller ones, around 54 cm in length, often have a fingerboard and the larger instruments are around 68 cm in length. Also, the kemane of Cappadocia, is a type of ‘large kemenche’, which, as seen in Turkish Museums, have six strings with a further six sympathetic strings under the fingerboards.

In contrast to the kementsé, or kemenche, according to the Greek kemane player, George Poulantzaklis, the kemane is between 55 cm and 70 cm in length and only larger in volume and shape than the kemenche. The instruments Poulantzaklis uses have four strings with four other strings (sympathetica) which create a vibration (clamour) to the first four.

The kemenche is one of the four basic types of lyra. The other three, the Cretan lyra, the lyra of the Dodekanisa and the Thrakian lyra, are pear-shaped with three or four metal or gut strings which are stopped from the side by the fingernails (which differs from the kemenche where strings are stopped by the finger tips). Small pellet-bells attached on the bow (which provide rhythmic accompaniment), on the pear-shaped lyra, were once common (until around World War II), but are now rare.

History

The origin and history of the kemenche are obscure. The earliest known representation of a kemenche appears to be in an album of watercolors of Constantinople painted by Amedeo Preziosi. The Maltese Preziosi was active in Constantinople from about 1840 onwards and was the chief figure in the Ottoman art world in the 1870s.

Matthaios Tsahourides, researcher and respected kemenche player, believes the instrument (which he prefers to call the Pontic lyra) and its music has similar roots in Medieval Europe and Byzantium. If the construction of the instrument with other European instruments is examined, the kemenche looks more like a Byzantine or Medieval European instrument, than an instrument of Asian origin.

The kemenche was taken to the South Caucasus in the last half of the 19th century and the first quarter of the 20th century by Pontic immigrants and refugees.

The word kemenche is believed to be derived from the Persian words keman (bow) and che (little). The kamancheh or kamāncha is a Persian bowed string instrument related to the bowed rebab

(the historical ancestor of the kamancheh), and also to the bowed Byzantine lira which is an ancestor of the European violin family. Other variations of the kemenche are the Kemona and the Kemane.

Geographically the Pontic lyra was played only in the areas which once bordered the Byzantine Empire of Trebizond (from Samsun to just east of Trabzon, and also inland). Today, in this region situated in north-eastern Turkey, the kemenche is still made by local luthiers and played extensively and is referred to as Karadeniz kemençesi. However, the Karadeniz kemençesi is a slightly lighter instrument due to its lower depth. It also has fewer sound holes and therefore sounds slightly different. The instrument is generally not played in other parts of Turkey.

The Rum (Orthodox Greeks) who lived in this region for nearly 3000 years, and who were expelled in 1923 as part of the forcible exchange of populations between Greece and Turkey, sometimes simply call the instrument a ‘lyra’.

Source: Sam Topalidis (2010): The Kemenche – https://pontosworld.com/index.php/music/iistruments/326-the-kemenche-2

The Pontic Lyra (Kemenche) – https://pontosworld.com/index.php/music/iistruments/331-the-pontic-lyra

Playing the Pontic Lyra:

(Tik Santas)

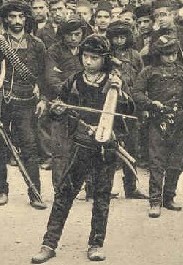

Serra (Horon), Kótsari (Κότσαρι) and many others: The dances of the Pontic Greeks

Folklore in mountain regions is always diversified. Traditional costumes, dances, songs, but also dialects differ from valley to valley. This also applies to the Pontos.

Today 50 to 80 Pontic dances are known. Some of them are widespread and were and are danced everywhere, but there are also some that are hardly known. Each region of the Pontos had its own specific regional dances.

The Pontic dances have their origin in the dances of ancient Greece, many of which were dedicated to specific deities. They are social dances, which – depending on the occasion – have different dance emphases; they are divided into warlike, religious-ritual and peaceful dances. Their social character is shown by the fact that they are circle and group dances. They are of great importance to the Pontic Greeks because they helped to maintain their tradition and identity, both in the Pontos under Ottoman rule and in exile after the ‘uprooting’ in 1923.

In the Pontic dances, together with the dancing people, the lyricist also takes part. In the dances, which are accompanied by his song, he himself dances with his lyre. He runs from one end to the other, from one dancer to the other, he jumps in rhythm with the dancers and shows an uncontrolled, enthusiastic, Dionysian side.

Most Pontic dances were pure male or female dances. There were only a few mixed dances, which were danced only on special occasions. For example Kotsagél, which is danced at a wedding as the last dance by all relatives of the bridal couple, or the so-called Kodespiniaká dances, which were called that because they were danced by adult men and women and sometimes even led by a woman (Kodéspina = mistress; lady of the house). The Omál, the Dipát and the Tik belong to the Kodespiniaká. Today all dances are danced mixed, except the Pyrrhíchios, which was and is only danced by men (or women in men’s costume).

The majority of Pontic society was rural. So we know many peaceful peasant dances, for example Trygóna, Kótsari, Saríkus. The religious-ritual dances revealed the loyalty of the Pontians to their customs and traditions and the respect for the values of the society they lived in. The religious-ritual dances include the wedding dances such as Thímisma and Kotsagél. The only martial dance is the Pyrrhíchios.

The Pontic dance is a group dance, and there are no distinction of location or class, no best or worst. The circle of dancers unites all together and the ‘I’ merges into the ‘we’. The first becomes the last and the last the first in the dance circle.

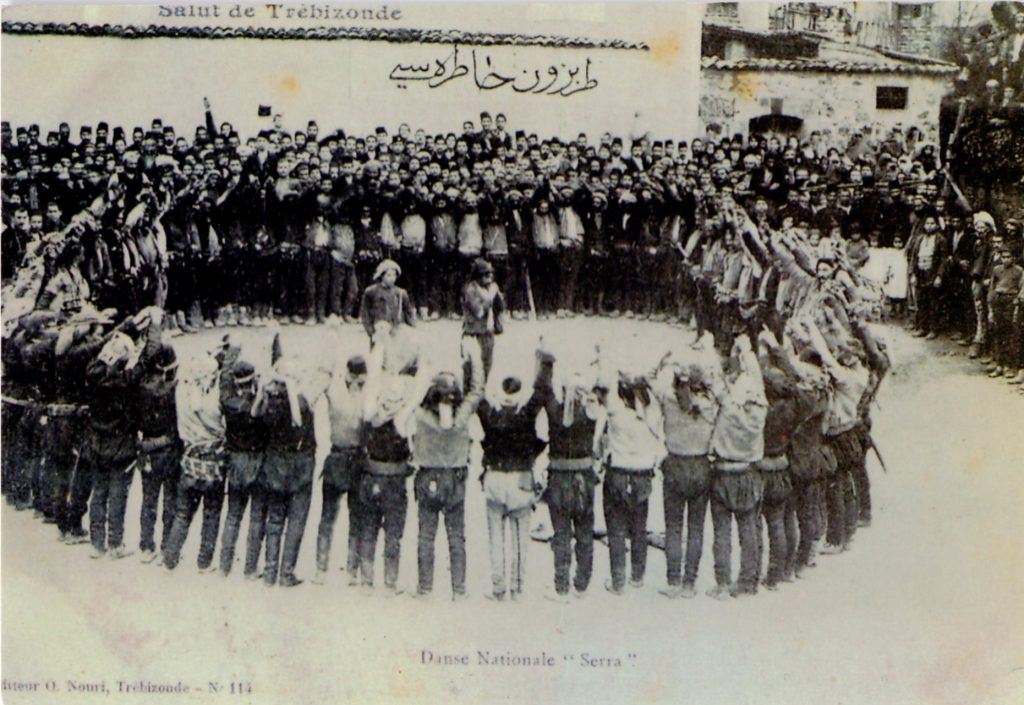

The Horon (Serra; Lazikon)

Probably the most archaic and well-known dance is Horon (also: Khoron; Horonu; from Greek choros (χορός) – ‘choir’, ‘dance’) or Ser(r)a (probably after the river of the same name west of the city of Platana [Tr.: Akçaabat]).

This dance is also referred to as the Pyrrichio or Lazikon. The ancient origins of the dance can be proven as the dance moves resemble those of the ancient Pyrrhic dance.

According to Plato, Pyrrhíchios means ‘Armed Dance’, a dance symbolizing war, in the course of which attack and defense are represented. Plato considered it essential that women and girls, as well as men and boys, should practice the dance of arms and warfare. He points out “that there are countless masses of women on the Pontos, called Sauromantes, who are prescribed the same exercises and performances as men, not only in riding, but also in archery and the other arts of arms”. (Plato, Laws, Book 7)

Then as now, Pyrrhíchios is danced in two ways: one is when two men armed with knives circle each other with dancing movements, they wrestle and try to defeat each other. This version is still danced today under the name ‘Mazér’ (from Greek “machéri” = knife). In the second version the warrior-dancers hold each other’s hands in a round dance. They are armed and ready for a joint fight. This kind of Pyrrhíchios is danced today under the name Sérra.

In the periodical Pontiaki Estia (1956, 4th edition, #76) Mouzenidis states that the Serra is a dramatic dance and analyses it as follows:

Firstly the dance comprises 3 parts. In the first part the dancers who are characterizing the people (laos) as a whole, hold each other by the hand and with arms raised begin to dance slowly with a mood of joy expressed on their faces. Gradually the dance moves into the 2nd part. Joy turns to unease and the dancers’ bodies increase intensity their hands moving rhythmically forward and then backward attempting to keep their bodies upright so as not to fall. At this point the dancer is trying to mimic an injured fighter trying to cling to life and to win. And although the body is leaning over, small energetic and sudden movements show the wounded fighter is trying to survive. In the 3rd phase redemption arrives. The dancer’s body which was bent over and almost touching the ground gains strength and the dancer begins to jump with his legs spread wide apart and his body becomes erect like a column and his head is held up with pride and looking upwards.

K. Papamihalopoulos in his work titled A tour of Pontus (1904) wrote the following about the Serra after touring the region and seeing the dance in person:

It is a war dance characterized by directional body movements by dancers that are joined tightly together. The dance consists of violent movements of the body, strong foot taps on the floor, contractions of body muscles, an enthusiasm and cheerfulness that grips the dancer, and a spark which transmits emotion. A dance identified by its originality and splendor of a group which quite rightly classifies it as one of the most famous dances in the entire world. [9]

The Pyrrhic Dance

The Pyrrhic dance, which the Serra is based on, was an armed dance of ancient Greek origin. The exact steps are not known but the movement was definitely quick and combat-like. According to Strabo (Gr.: Strávonas), an ancient geographer and historian from the Pontic city auf Amásia, the origins of the dance and also its name comes from the contorted movements in the death of Achilles’ son Pyrrhus as described by Euripides in Andromache.

A more likely argument is that the Pyrrhic’s birthplace was in Crete due to its association to the myth of the Curetes guarding infant Zeus with warlike movements and noises of clashing swords and shields. By 1250 B.C. the dance was widespread in Crete, mainland Greece and Asia Minor. It is mentioned in the Iliad (8th century B.C.) where it’s suggested the name derives from pyra (pyre) or pyr meaning fire.[10]

The Kótsari (Ko(t)chari)

Although the Kochari (or Kotchari; in Greek pronunciation Kotsari; Grk.: Κότσαρι) is a popular dance amongst Pontic Greeks second only in popularity to the Serra, it seems to be an import from the South Caucasus, namely from neighboring Armenia. It was danced in the eastern regions of Pontos such as Argyroupolis (Gümüşhane), Bayburt (Arm.: Baberd) and primarily by the Pontic people of Kars, the ancient capital city of the Armenian Bagratid Kingdom. It was also danced in the Upper Matsouka region. The dance was introduced to the Upper Matsoukans as late as in the last decades prior to the forcible population Exchange (1923) and it’s sometimes said that the Matsoukans learnt the dance at the festivals of Panagia Soumela from worshippers who originated from the home of the dance, i.e. those from the easternmost regions of Pontos and the Caucasus.[11]

There is an Armenian and a Greek ethymology for the origin and the name of this group dance: Ko(t)chari (from Armenian ‘քոչէլ’ (ko(t)chel – to move around; to nomadize) is a shepherd dance, which has been registered on the UNESCO World Heritage List since 2017.[12]

Jannis Korosidis characterizes the Pontic Greek variant of the Ko(t)chari as follows:

„This dance is danced by the rural population in the south of the Pontos, especially by the Pontic Greeks of the Caucasus. Its name refers to the Pontic word for ram, the billy goat, the sacred animal in the worship of Dionysos. The fast, springy, double-footed movements of the dancers remind us of the jumps of the billy goat during the rut, at the beginning of spring, the time of the religious veneration of Dionysos. The worship of the god who was originally the patron saint of the farmers is also recalled by the first steps of the dance, which were performed by the dancers to get onto the stage as early as in ancient times.

‘Stamátima’, a typical figure in Kótsari, a short ‘behaviour’ during the dance, is considered an element of ancient religious worship and has been preserved in the Pontic dance tradition until today. During their magical services, the dancers suddenly stopped and then started again with the aim of attracting the attention of the audience or the worshipped deity.”[13]

Diverging explanations are quoted in the dance’s description by Pontosworld:

“Its name is derived from the manner in which it’s danced and in particular the 2 limp movements (the first 4 steps of the dance), which are executed with synchronous stepping of the heel (the kotsi) on the ground. In Greek, the word koutso means limp, and the heel of the foot is called the kotsi (pl. kotsia).

Another explanation of the name is that it describes the manner in which the legs-knees are shaken and locked by metatarsal movement. The dance relies on powerful foot movement/limps and hence it’s the dancer’s feet which keep the dancer upright. Whilst the above descriptions are considered arbitrary another explanation is that it was named after an anonymous dancer by the name of Kotsari (or Konstantinos) although this explanation does seem unlikely.

The Kotsari belongs to the family of straight step heel dances which rely on heel steps. Such dances also exist in Greece, the Aegean islands, Crete and generally amongst the races of Asia minor since Ancient times.

It’s a double rhythm fast dance similar to the Susta dance of Rhodes and the Maleviziotic-Castrino dance of Crete. The dancers hold each other at the shoulder in a circle but more commonly in a semi-circle. There are 8 steps in the dance which are broken down into 2 parts. The first 4 movements are the 2 on the spot jumps, in other words the limp steps of the left heel – this is the first part of the dance. The next 4 steps are basic ones and move the dancer towards the right.

The dance started off as a male only dance. Some researchers have classified it as a mountain war dance. Later it became acceptable for women to dance it also.”[14]

Customs and Traditions of the Pontic Greeks

The Momogeri

The Momogeri are magical and religious celebrations that took place in Pontos between Christmas and the feast of Epiphany (feast of the Apparition of the Lord; in the West this day coincides with the feast of the Magi). On the day of the Epiphany the performances came to an end, as the evil winter spirits were driven out with the apparition of the Lord.

Momos was in ancient times the Greek god of nagging, the personification of rebuke and defamation, a master of sharp-tongued criticism who did not even stop at the gods. The priests of the god Momos are called Momogeri or his followers, who mock people and events by dancing and singing.

Around 400 A.D., Bishop Asterios of Amasseia (city in Pontos; today’s Amasya in Turkey) reports about a celebration in which people dressed up on January 1st.

These celebrations are connected with the celebrations of the god Dionysos in ancient Hellas and have in common, apart from mockery, the disguise and masquerade. The Momogeri are self-staged performances by disguised theatre groups, which were played in the courtyards, at street crossings or in central squares. The disguise with animal skins, horns, fox and hare tails, is evidence of the ancient origin of some of the figures. The use of face coverings and animal skins is widespread in all ancient cultures. The masked man equates himself with the deity to whom the holy animal belongs. Likewise, the dried fruits, herbs, fruit and other symbols of fertility worn around the neck by some theatre group members or the use of sticks by the leader of the theatre group bear witness to the magical and symbolic origin of these celebrations.

Usually the theatre group was formed by young people originating from the same village. The performances were always accompanied by music players. Dance and singing were integral parts of each performance.

The content of the performances is usually humorous, which is why the Momogeri are sometimes called comedy. However, comedy sometimes took on social dimensions and served to attack the corruption and licentiousness of the conquerors (Ottomans).

One of the main roles in the performances is played by the bride, who symbolises the vegetation and fertility of the earth. The confrontation between two men, a young man and an old man (the young man embodies the new year, the old man the past year), with the aim of winning the bride and, finally, the victory of the younger man are remnants of the ancient origins. In the performances there is also often the healing of an injured person or the resurrection of a deceased person, as well as dancing and a happy ending.

The performances have lost their original character over the millennia and were mainly for entertainment. The proceeds in kind were either distributed to needy families or were used up at the theatre group’s celebrations. The monetary income was almost exclusively transferred to the community treasury, the school or the church.

Translated and quoted from: Verein der Griechen aus Pontos in München e.V. – http://pontos-muenchen-ev.de/de/pontos/ithi-ethima/momogeroi/

“A Multiethnic Seaside Town”: Trebizond in October 1895

“A multiethnic seaside town inhabited by 20,000 Turks, 15,000 Greeks, and 7,000 Armenians, Trabzon in the 1890s was ripe for tensions. Turks in the area claimed they feared large-scale Armenian violence, though as one missionary put it, ‘it seems incredible that they could have been sincere in this.’

‘Rumors of massacres at Constantinople tended to aggravate matters,’ Longworth reported. There was considerable homegrown instability, too. On October 2, 1895, Lieutenant General Bahri Pasha, the outgoing vali of Van, was nearly assassinated in Trabzon, on his way to Constantinople. Bahri had been walking with the Trabzon town commandant, Ahmed Hamdi Pasha, when both were lightly wounded by a gunman. The shooter was not caught, but the Turks charged two ‘accomplices.’

The situation escalated further on the night of October 4, when ‘large bands of armed Muslims from the neighboring villages,’ intent on plunder, attacked Christian houses, firing guns and breaking in doors and windows. A rumor then spread that Christians were massacring Turks—or, alternatively, that Armenians had assassinated the vali. A mob of ‘at least 3,000’ mustered, ‘with knives, pistols and revolvers,’ and rushed through the streets. Christians fled to consulates and public buildings. But the vali, Kadri Bey, intervened along with his troops and some Muslim notables. They arrested the ring-leaders and ‘unmercifully beat’ many of the ‘rowdies.’ The crowd dispersed before any lives were lost. The next day, the local consuls—British, Russian, French, Belgian, Austrian, Greek, Persian, and Italian- ostentatiously rode in procession down the main street to government house. Their aim, Longworth explained, was to ‘calm the fears of the Christians and strike fear in the hearts of the Turks!’

The Turks were not impressed. On October 8, at about eleven o’clock in the morning, the mayhem in Trabzon began ‘like a clap of thunder in a clear sky.’ Turkish authorities later claimed that ‘it was impossible to determine on which side the brawl began’ and that Armenians ‘from their shops and bazaars . . . indeed from anywhere and everywhere . . . fired at random on soldiers, police, zapties, and citizens alike’ such that the ‘crowd which found itself in the square and the adjoining streets was obliged to respond.’ But Western observers—not to mention Armenian witnesses—knew just what they saw: the Turks had initiated the massacre without provocation. According to an unsigned report, probably by an American missionary, Armenians were shot down in the street ‘or sitting quietly at their shop doors. . . . Some were slashed with swords. The Turks ‘passed through the quarters . . . killing the men and large boys, generally permitting the women and younger children to live. For five hours this horrid work of human butchery went on’. (…)”

Excerpted from: Morris, Benny; Ze’evi, Dror: The Thirty-Year Genocide: Turkey’s Destruction of Its Christian Minorities, 1894-1924. Cambridge, MA; London: Harvard University Press, 2019, p. 73f.

In Trebizond, on 8 October 1895, “Armenian shops were looted, merchants killed on the spot. Homes, ransacked. In one day nearly a thousand Armenians lay dead in the ruin. But this was just the beginning. That same month massacres took place at Erzinjan [Erzincan], Erzurum, Gumushkhane [Gümüşhane], Baiburt, Urfa, and Bitlis.”[15]

1914-1923: Repetitive Boycott, Discrimination, Persecution, Massacres, Deportations and Expulsions

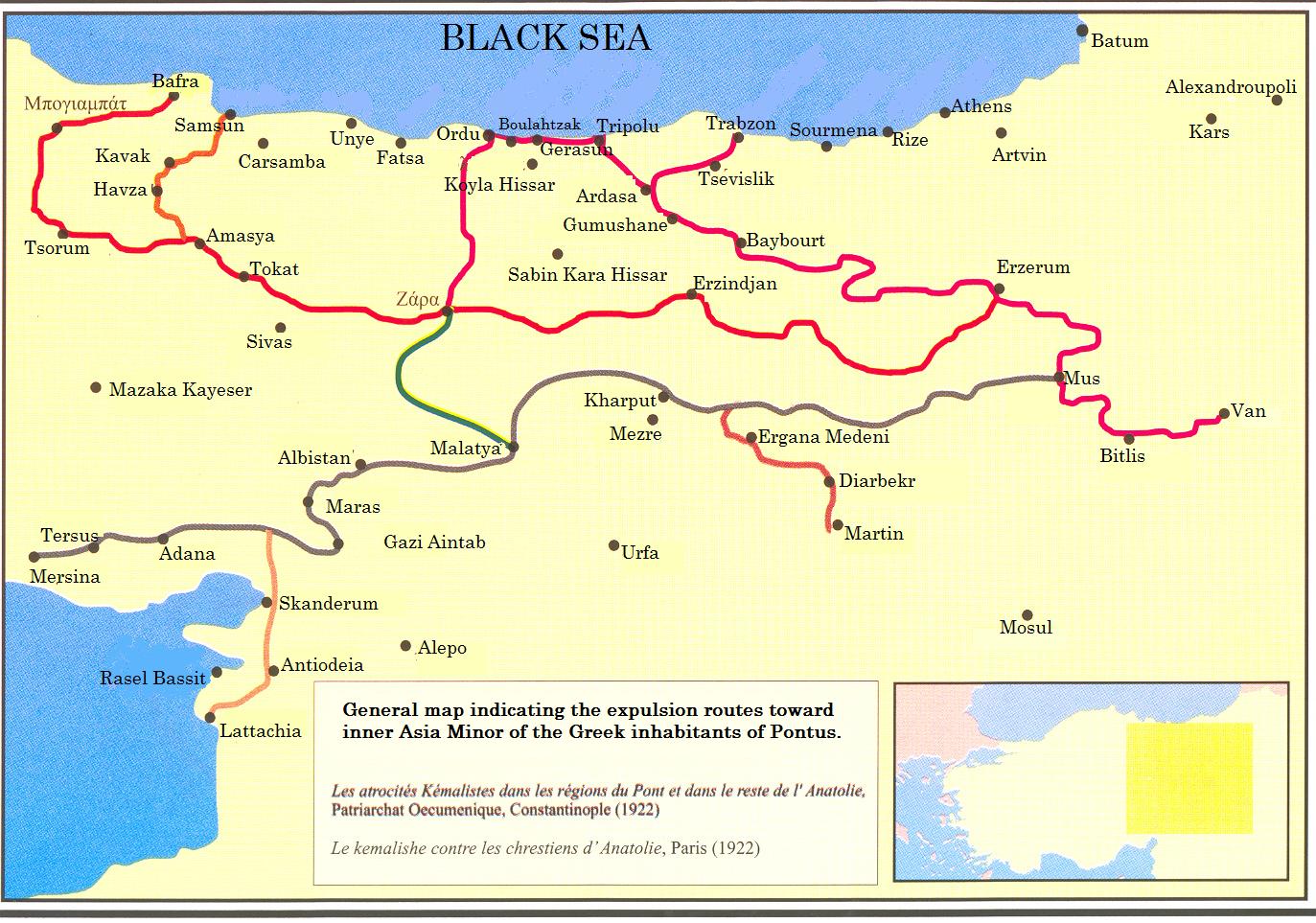

The Christian population of the Trebizond province was repeatedly subjected to persecution, massacres, deportations and mass expulsions before, during and after the First World War. During the World War, the western part of the province was particularly affected.

According to a 1918 report by the Hellenic Foreign Ministry, a roughly estimated 200,000 Greek Orthodox Christians were deported within the Ottoman Empire during World War I.[16] Of these, 30,000 were ‘evacuated’ in February 1918 alone from the sancak Samsun, and 22,336 until January 1917 from the kaza of Giresun (Kerasus, Kerasounta).[17] These organized forced relocations are not to be confused with forced evictions, usually of entire villages that have been terrorized, plundered and burned down. Their inhabitants could only escape to the mountains and forests, where many of them died of exhaustion, hunger or diseases.