Toponym

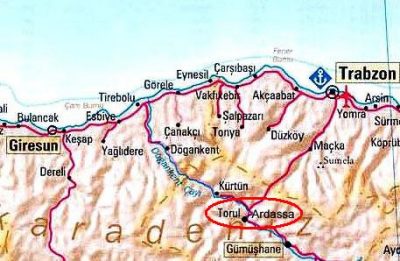

Around the year 350 BC Xenophon called the region surrounding the Torul River Drílai. The district centre was known as Ardas(s)a (Άρδασα) until the middle of the 20th century; the Turkish toponym Torul has been documented since the year 1515.

Population

At the end of the 19th century, more than half of the population of the kaza Torul was Greek.

The Last Christian Stronghold in Asia Minor? The Fall of the Golacha Fortress (Trk.: Colaşana)

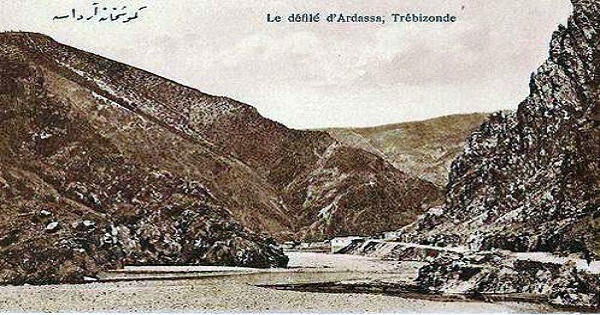

“Several times in the meantime, the nearby Muhammadan tribes felt the fury of these rough Alpine inhabitants, but especially during the eleventh year of the reign of John Alexis [Emperor Alexios (Iōannēs) III. Megas Komnēnos], when the Emir of Paipert [Armenian: Baberd; Bayburt] made hostile attacks against the forts of New Matzuka [Maçka], Larachane and Chasdenicha. He himself, with most of his army, was crushed by the inhabitants in the narrow passages, and the heads of the slain were carried around the capital for display. In the same way, at that time the Emir of Arzinga [Erzincan] had to withdraw from the siege of the mountain fortress Golacha without having achieved anything. The dispute over the beautiful alpine land of Chaldia, in which Golacha lay, continued until the nineteenth year of the emperor’s reign, when the Emir Kılıc-Arslan took the named mountain fortress by a sudden attack, and drove the Trapezuntians out of all Chaldia. Although the old inhabitants conquered the lost castle and land six years later, they were immediately driven out for the second time and forever by the same Turkomans. In order to wipe out the shame of these repeated defeats, Alexis took courage and made an attempt to conquer the beautiful Cheriane again, but lost part of his army, partly by the sword of the enemy, partly by the fury of the cold, because he committed the folly of waging war on a high Alpine country in the month of January.”

Quoted from: Fallmerayer, Jacob Philipp: Geschichte des Kaiserthums von Trapezunt. München: Verlag Anton Weber, 1827, p. 197f.

Postscriptum

Even after the fall of the Empire of Trebizond, some mountain fortresses continued to resist the Ottomans. The region was not completely subjugated until 1479, when the Golacha fortress, the last Christian outpost in Asia Minor, fell to the Ottomans.

While J.P. Fallmerayer assumed the fall of Golacha already under the rule of the Trebizond emperor Alexios (Iōannēs) Megas Komnēnos (1349-1390), more recent researchers assume the regional continuity of Christian rule in the erstwhile Byzantine Theme Chaldia: Anthony Bryer and D. Winfield identified the ‘mountain fortress’ Golacha with the fortress Dorile or Dorilios (Dorilion), which the Castilian envoy Ruy Gonzales de Clavigio visited at the end of April 1404 on his journey to Samarkand south of Trebizond. In Byzantine times, this castle, situated in the later Ottoman kaza Torul, was the seat of the Duces of Chaldia, provided by the Kabazitai family. Fought several times between Byzantines and Turks, it became, from 1461-1479, “the capital of the (still independent) Principality of Torul, which represented ‘the last vestige of the empire of Trebizond’ and whose name (which is, however, a regional designation) corresponded exactly to the place name Dorile/Doryle. (One) may presume with caution that also after 1479 there was again a renewal of the Christian(?) post-Byzantine local rule there – admittedly nowhere registered so far – which was then finally broken in 1525/26; but this finding would still have to be checked by the Ottoman side.”[1]

Destruction

During the First World War, Russian forces occupied the eastern part of the Pontos, including parts of sancak Gümüşhane (20 July 1916 to 15 February 1918). “Muslims from villages and cities occupied by the Russian army would leave their homes and flee in panic towards Ottoman-occupied locations, afraid of retaliation for the Armenian massacre. In the course of their retreat, however, they would invade Greek Pontian villages, sack them, rape women, kill or abuse the villagers, and leave. Such disasters occurred in Maςka, Torul, Ardasa, Tsiti, Abrikanton, Hopsa, Koronyxa, Tsarouch, Kirhamen, Chapuk, Maceran, Sarandar, Fitiena, Goli, and other villages. The Greek inhabitants of these villages abandoned their homes and took to the mountains, often joining battle with the Turkish-Lazi perpetrators.”[2]

1919: ‘A Living Hell’

“Despite stern words from the Great Powers to the government of Damat Ferit and to local authorities, the violence, looting and murders continued on a daily basis: ‘There was no response to the appeals; every day there is news from the outlying area that the Greeks have been turned into veritable slaves. The district of Torul [in the vicinity of Gümüşhane], which up to then had been relatively quiet, was transformed into a living hell. The property and honour of these unfortunate Christians was taken away from them, leaving just dry and empty lives which, when the bands so wished, they were also deprived of.’”[3]

“…plundered, massacred and destroyed everything and all, that was Greek”: The expulsion of the Greek inhabitants of the Torul Kaza in 1916

In a documentation of the Ecumenical Patriarchate from 1919 it says about the situation of the Greek population in the Kaza Torul of 1916, before the Russian occupation:

“Torul-Arghyroupolis Region:

1.Koroxena, 2. Madjera, 3. Phytiana, 4. Amvriki. – Abandoning their entire fortunes, the inhabitants of these villages, in a naked and starving condition, wandered for whole weeks in the mountains. Women and young girls were violated, and a woman with her child, natives of Amvriki, and five inhabitants of Phytiana, were murdered. The churches were plundered first and then set fire to. After roaming about for many days, many returned to their homes, but no sooner was Ardache [Ardasa] taken (8 July 1916), than the Turks, after making them pay heavy ransoms for their honour and lives, expelled the inhabitants to the regions occupied by the Russians.

5.Papavram, 6. Sarandar, 7. Iledjouk, 8. Hopsia, 9. Gholi, 10. Fetikes. – These villages were plundered and burnt. Their inhabitants took to the mountains. Kyriakos Mandedjidis of Papavram was burnt on a funeral pile. Fifteen men of Sarandar, four of Iledjouk, ten of Hopsi and six of Gholi were also slaughtered.

11.Mavrena, 12. Sarpis-Köy, 13. Avliana, 14. Adyssa, 15. Artaper. – These villages shared the same fate. Two inhabitants of Adyssa were murdered.

16.Mangadi, 17. Ak-Çal, 18. Gargaena, 19. Desmena, 20. Simikli, 21. Sari-Papa, 22. Beytarla. – These villages were ruined in the same manner. Five inhabitants of Ak-Çal, fifteen of Garhaena [sic!], twenty of Desmena, sixty of Simikli, and fifty of Sari-Papa were murdered. Many young girls as well as the nuns of the monastery of Simikli, were violated.

Besides these twenty-two villages, ten smaller groupings: Kanak, Kelenta, Derena, Almi, Kalitz, Ayani, Simera, Ramatanta and Massanant, forming a Greek population of some 2,300 souls, were scattered, after their homes were first plundered and then burnt down.

At the approach of the occupation of Ardache, the fugitive Turks formed bands of irregulars and plundered, massacred and destroyed everything and all, that was Greek. The greatest catastrophe befell the remaining inhabitants of Kurtakous, who were deported to Sivas and Tokat. By order of the sub-governor, two days before the occupation of Ardache, the houses and shops of the Christians were plundered, and set fire to with petroleum.

Source: Ecumenical Patriarchate: The Persecution of the Greeks in Turkey, 1914-1918. Constantinople: (London, Printed by Hesperia Press), 1919, p. 100f. – https://archive.org/details/persecutionofgre00consrich/page/100/mode/2up

Ardas(s)a / Torul Town

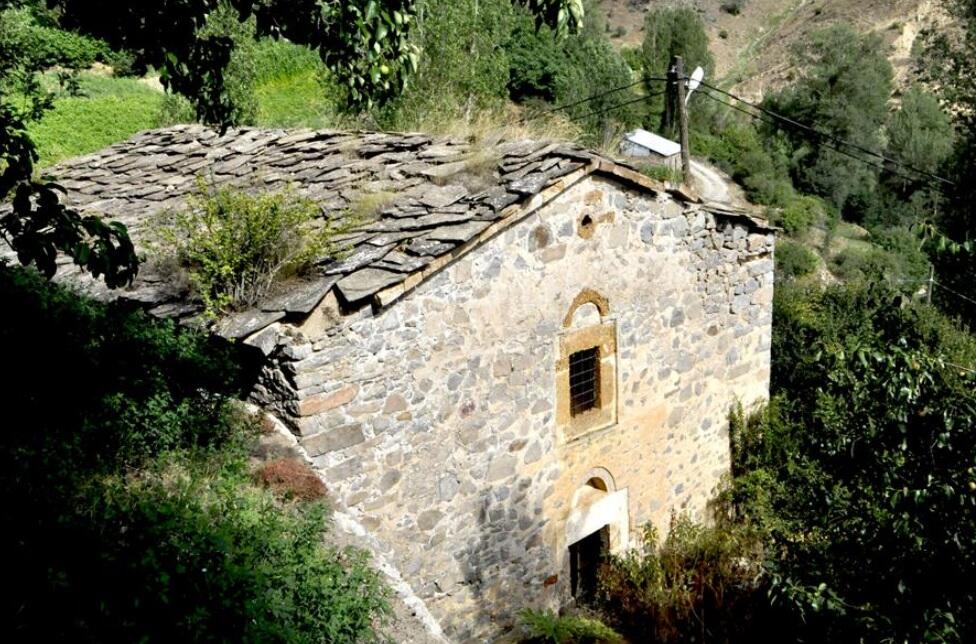

Ardasa was in the district of Chaldia in Pontos, 15-20 km North-West of Argyroupolis (Gümüşhane). It is identified with the ancient city of Dorylaion from which its current name of Torul appears to originate from. The city is built on the banks of the Upper Harsiote (or Kanis) river. A castle is built on the side and north of this river as evidenced by Clavijo during his travels through Chaldia on 30 April 1404.

During the middle ages Ardasa existed in Chaldia, one of the 6 powerful Byzantine seats, and was named Mesohaldion. It was the seat of the powerful family fiefdom of the Kabazites, and the episcopal seat which was governed by the Diocese of Neocaesareia (Niksar). Anthony Bryer states that in the early 14th century, Constantine Loukites endowed each of St Eugenios’ companions with specific birthplaces in Chaldia. Loukites awarded St. Valerian a hamlet near Ardasa as his birthplace: Εδίσκη (Άδισα, or Adise, now Yildiz).

Under Ottoman rule, Ardasa was devastated and depopulated whereupon Turkish noble Osman Bey moved in from the village of Monastir (Demirkapi) of Amprikanton, and chose to make it his new seat. From then on, it became a subdistrict of the Ottoman Empire and a commercial/transport center of the wider region, in which there existed a number of Greek villages.

In 1901 the Ardasa bridge was built by chief builder N. Demirtzoglou of Santa and provided an increase in movement and transport to the town. The bridge still exists today. According to Pantelis Melanofridis the Bridge of Ardasa is that which is referred to in the famous poem ‘Tis Trixas to Yefiri‘.

40 Muslim and 5 Christian families lived in Ardasa. Many of the Greek families maintained businesses. Before the forcible population exchange between Greece and Turkey (1923), Ardasa comprised an administrative building, a court, a post office, businesses and inns as well as a church which was dedicated in memory of Saint Sophia and the Dormition of the Virgin Mary.

Some Greek settlements of the Ardasa region

Ardas(s)a, Adisa, Avliana, Varaton, Bartanton, Yaratzanton, Dipotamos, Kagkelina, Karel, Korkotas, Kodona, Lapadion, Martin, Maurena, Mesohor, Mourtazi, Palihor, Pachtsopon, Pivera, Rak (Riaki). Sarpiska, Tsak, Tsarouchonos, Tsimprika, Tsiti Large, Tsiti Small, Haviana.

References:

Eastern Pontus, by Savvas Kalenteridis

The Encyclopedia of Pontian Hellenism

The Byzantine Monuments and Topography of the Pontos , A. Bryer, D. Winfield

Source: https://pontosworld.com/index.php/pontus/places/183-ardassa-torul