Population

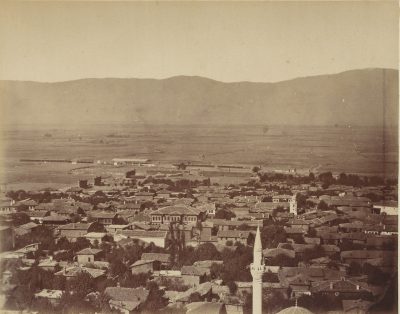

In 1911, Ottoman Magnesia had an overall population of 35,000.[1]

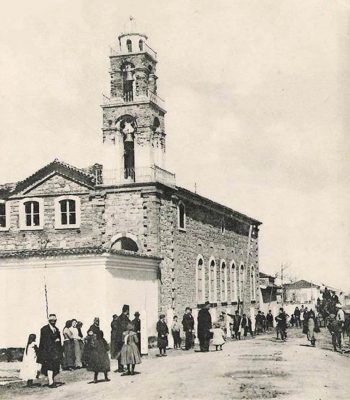

The Greek population of the kaza of Manisa belonged to the Diocese of Ephesos (with eighty-five communities and 164,467 Greek Orthodox inhabitants)[2].

Notable Greek-Orthodox Christians

- Saint Gregory (Orologas) of Kydonies the Ethno-Hieromartyr, also Gregory of Cydoniae (Γρηγόριος Ωρολογάς – Gregorios Orologas), b. 1864, Manisa–d. 3 October 1922, Ayvalık: Greek Orthodox metropolitan bishop in the early 20th century in northwest Anatolia

History

Luwians, Hittites, Phrygians and Lydians

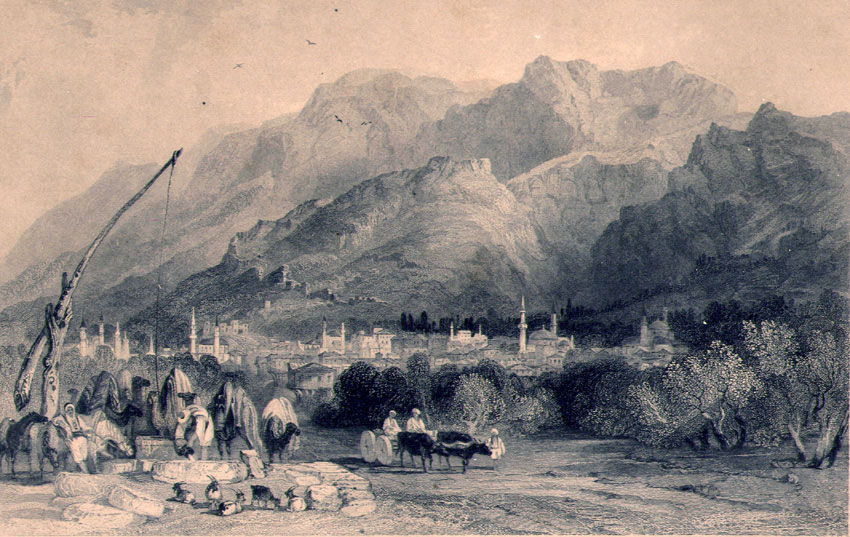

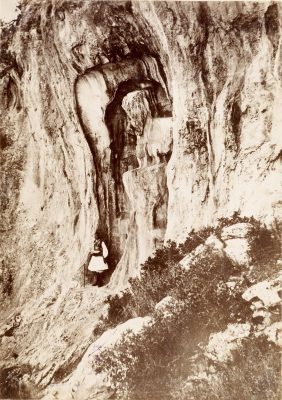

Central and southern parts of western Anatolia entered history with the still obscure Luwian kingdom of Arzawa, probably offshoots, as well as neighbors and, after around 1320 B.C., vassals of the Hittite Empire. Cybele monument located at Akpınar on the northern flank of Mount Sipylos, at a distance of 7 km from Manisa on the road to Turgutlu is, along with the King of Mira rock relief at Mount Nif near Kemalpaşa and a number of cuneiform tablet records are among the principal evidence of extension of Hittite control and influence in western Anatolia based on local principalities. Cybele monument by itself represents a step of innovation in Hittite art where full-faced figures in high relief are rare. The first millennium B.C. saw the emergence in the region of “Phrygians” and “Maeonians“, the accounts concerning which are still blended with myths, and finally of Lydians. Such semi-legendary figures like the local ruler Tantalos, his son Pelops, his daughter Niobe, the departure of a sizable part of the region’s population from their shores to found, according to one account, the future Etruscan civilization in present-day Italy, are all centered around Mount Sipylos, where the first urban settlement was probably located, and date from the period prior to the emergence of the Lydian Mermnad dynasty. It has also been suggested that the mountain could be the geographical setting for Baucis and Philemon tale as well, while most sources still usually associate it with Tyana (Hittite Tuwanuwa) in modern-day Kemerhisar near Niğde.

In the early 7th century B.C., the Lydians under the newly established Mermnad dynasty, with the present-day Manisa region as their heartland expanded their control over a large part of Anatolia, ruling from their capital “Sfard” (Sard, Sardes, Sardis) situated more inland at a distance of 62 km from Manisa. The vestiges from their capital which reached our day bring together remains from several successive civilizations.

Hellenistic, Roman and Byzantine periods

In classical antiquity, Romans knew the city as Magnesia ad Sipylum. There, in 190 B.C., forces of the Roman Republic defeated the Seleucid king Antiochus the Great in the Battle of Magnesia. Magnesia ad Sipylum became a city of importance under Roman rule, and though nearly destroyed by an earthquake in the reign of Tiberius (Roman Emperor from 14 A.D. to 37 A.D.), was restored by that emperor and flourished through the period of the Roman empire.

In 1076 the Byzantine Empire lost the city to the Seljuks in the aftermath of the 1071 Battle of Mantzikert. The subsequent Crusader victory at the Battle of Dorylaeum (1097) allowed the Byzantine Emperor Alexios I to recover Magnesia. It was an important regional centre under Byzantine rule, and during the 13th-century interlude of the Empire of Nicea of 1204 to 1261. Magnesia housed the Imperial mint, the Imperial treasury, and served as the functional capital of the Empire of Nicea until the recovery of Constantinople in 1261. Ruins of the Nicean-era fortifications attest to the city’s importance in the Late Byzantine period, a fact also noted by the Byzantine historian George Akropolites, writing in the 13th century.

Turkish era (Seljuk, Saruhan and early Ottoman periods)

In the early 13th century the region of Magnesia was subject to repeated raids by invading Turkish bands. The local population was unable to repulse the Turkish raids. Thus, after an unsuccessful defense led by the Byzantine Emperor most inhabitants fled to the Aegean coast and the European part of the Byzantine Empire. As a result of the Turkish invasion in the region and the destruction of the city the area was largely abandoned. In 1313, Manisa became a permanent Turkish possession when taken by the Beylik of Saruhan, led by the Bey of the same name who had started out as a tributary of the Seljuks and who reigned until 1346. His sons held the region until 1390, when the first incorporation of their lands into the expanding Ottoman state took place. After a brief interval caused by the Ottoman interregnum after the Battle of Ankara, Manisa and its surroundings definitely became part of the Ottoman Empire in 1410.

Even during the 15th century Magnesia was recorded as being in complete ruins due to the previous Turkish raids. As the central town of the Ottoman Empire’s Saruhan sancak, the city became the training ground for shahzades (crown princes), and it stood out as one of the wealthiest parts of the Empire with many examples of Ottoman architecture built. Although the sancak of Saruhan officially depended on the eyalet of Anadolu with its seat in Kütahya, a large degree of autonomy was left to the princes for them to acquire the experience of government. This practice was discontinued in 1595, largely due to the growing insecurity in the countryside, precursor of Jelali Revolts, and a violent earthquake dealt a severe blow to the Manisa region’s prosperity the same year.

Around 1700, Manisa counted about 2,000 taxpayers and 300 pious foundations (vakıf), was renowned for its cotton markets and a type of leather named after the city. Large parts of the population had begun settling and becoming sedentary and the city was a point of terminus for caravans from the east, with Smyrna’s growth still in its early stages. But already during the preceding century, influent western merchants such as Orlando, often in pact with local warlords such as Cennetoğlu, a brigand (sometimes cited as one of the first in line in western Anatolia’s long tradition of efes [leaders of irregular Turkish soldiers in the Aegean] to come) who in the 1620s had assembled a vast company of disbanded Ottoman soldiers and renegades and established control over much of the fertile land around Manisa, had triggered a movement of more commercially sensitive Greek and Jewish populations towards the port city.

Late-Ottoman Manisa

Magnesia was one of the first cities in the Ottoman Empire to benefit from the arrival of a railway line, with the 93 km Smyrna Cassaba Railway, whose construction was started from Smyrna in 1863 and which reached its first terminus at Manisa’s depending Kasaba in 1866. This railway was the third started within the territory of the Ottoman Empire at the time and the first finished within the present-day territory of Turkey.

Destruction

After the Young Turk revolution (1908) the local Greek community was subject to wide scale boycott, as noted by the local British ambassador.

Diocese of Ephesos, 1913-1914

“Violent persecutions occurred in this Diocese (…); murders took place all over the country and the inhabitants were kept in a constant state of uneasiness. The policy followed by the C.U.P. and its agents completed in 1914, the destruction premeditated by them.

On the 2nd March, 1913, a Turk wounded a young man named Athanasse Kabakli, who died after two days. On the morrow, a band of Turkish irregulars, armed to the teeth, entered the village of Basse Demirdjili [Base Demircilı] and proceeded to the requisition of all the dwellings in general, and after beating the muhtar and several notables, retired undisturbed. The pope (priest) of the village lodged a complaint, and as a result, his punishment by the local authorities was requested by the Turks. In the course of the same month the miller, Panayis Tsoulakis, was murdered and his corpse thrown into the river Azamet-Tsay.

Constantine Karamihalis was murdered in the chapel of St. George at Pergamos [Bergama]. On the 18th August, 1913, two Greeks, Dimitri Evang. Kaumissis and Demitri Ch. Nicolonis, natives of Neochori (Macedonia) were found slaughtered at Dere-Keuy [Dereköy] and Kurla near Magnesia.

On the 2nd of September, 1913, three Moslems took hold of a woman, Suzan Demitriou, in the village of Yukse-keuy [Yükseköy], on her way to the fountain. She was pregnant. After first satisfying their instincts of bestiality on her, they opened her abdomen, extracted the child and pitched both in a ditch. On the 29th September, 1913, Nicolas Demitriou was met on the road by gendarmes coming from Papazli (Magnesia [Manisa]). They murdered him. George Natsoulidis, a native of Baya of Zayori (Epirus) was killed by three Moslems on the 1st of October, 1913. Between the eighth and ninth of October, at night, four Cretan Moslems entered the coffee shop of Anast. Sp. Hassapi at Cassaba [Kasaba] (Magnesia), and massacred the tenant. A post-mortem was held. The police came to the conclusion that only professional butchers could slaughter in such a manner, so that they arrested some Christian butchers, and imprisoned them.

The foregoing list of crimes so carefully carried out clearly demonstrated the premeditated plan for the extermination of the Christian Greeks by Turkish officials and civilians. The local authorities did their best to throw dust into the eyes of the public by pretending to punish the perpetrators of such crimes. On the other hand, they encouraged and incited their continuation by distributing arms to the Moslem population of Menemen, Adramiti, Bourhanie, Pergamos, Phocoea [Foça], Vourla [Urla], Sivrissar, and New Ephesus (Scala Nova), while severe measures were being taken against well- to-do and peaceable Christian citizens, whom they often imprisoned and exiled without any cause or reason.

Notwithstanding all this, the Greek element remained firm and conscious of its own rights. The programme, however, of the Young Turks was bound to succeed. They had recourse to the boycott, which they exercised over all the diocese even more severely than in other places. The situation was daily rendered more critical. The Turks at first only threatened, but soon began to destroy the fortunes of the Christians by pulling up trees and vines, reaping crops, etc., assisted in their work by the Turkish immigrants.

Under date of the 28 April, 1914, loachim [Gounaris], the Metropolitan of Ephesus, writes : —

‘The boycott exerted against the Greeks, on the one hand, and the instalment of immigrants in the different communities on the other hand, render their position daily more difficult and critical. They already begin to apprehend, and even see the time, when giving way to the pressure exercised on them by the Moslems they will be obliged to abandon their homes.”

What he foresaw has unfortunately come to pass.”[3]

“Magnesia [Manisa] Region.

- SOMA. The economic crisis arising from the boycott and the plundering were the cause of the emigration of the Christians. At Magnesia proper, the situation was no better. Close to the village of Moutevelli, Athanasse Perivolaris was found assassinated in the fields. At Cassaba [Kasaba, also Turgutlu], a young Turk, fifteen years old, attacked and nearly killed a young Greek girl. Kyriakos Abalis, Costas Cavoukas, and George Haralambakis were murdered at Yaka-keuy [Yakaköy].

Certain agglomerations of villages not actually forming communities, such as Sakrani, Kirklar, Daglidena, Tsourouki, Fren-keuy [Frenköy], Kadi-keuy [Kadıköy], Tchirikdji, Kizil-Kitzili, Araplar, Karaklar, Tahtadji-keuy, Gum-Beili, Gioz-beili [Gözbeyli], and Saridjalar, expatriated in consequence of the threats and oppression.

The situation continued to be critical, for the Christians who still remained in these parts did not venture out into their fields, owing to the repeated murders committed in the country. It is a fact that this emigration had subsided in June, but it had only stopped because it was considered that the object of the Young Turks had been attained. They had distributed to the Moslem Mouhtars of the villages their famous instructions to the effect: ‘That the Christians should be driven out by main force and everything belonging to them should be plundered; that they should be outraged, and finally all the infidels should be annihilated.’ And this was done.

Mehmet Salih, Mahmout Handi and Moustafa Mouzaffer, furnished with letters of recommendation from the Vali of Smyrna, and passes free of charge on the railway lines, visited the different villages and towns of the province in order to preach violence against the Christians.

Far from being eliminated, the danger of the renewal of emigration seemed to increase daily, as the remaining Greek population was subjected to all kinds of violent persecution. The Metropolitan of Ephesus one day asked the Vali of Smyrna, Rahmi Bey, if he also would be sent away, and he received the following answer. ‘Yes, you will also have to go because you will not have any flock to preach to’.“[4]

1919-1922

Magnesia was temporarily occupied by the Greek Army on 26 May 1919 during the Greco-Turkish War (1919-1922), before finally being recaptured by Kemalist forces on 8 September 1922. In revenge, the retreating Hellenic forces burned the city as part of their scorched-earth policy. James Loder Park, the U.S. Vice-Consul in Constantinople at the time, who toured much of the devastated area immediately after the Greek evacuation, described the situation in the surrounding cities and towns of Smyrna he has seen, as follows: “Magnesia…almost completely wiped out by fire…10,300 houses, 15 mosques, 2 baths, 2,278 shops, 19 hotels, 26 villas…[destroyed].”[5] Patrick Balfour, 3rd Baron Kinross wrote: “Out of the eighteen thousand buildings in the historic holy city of Magnesia, only five hundred remained.”[6]

The spiral of violence that unfolded in Greek-Turkish relations not long before the Hellenic occupation of 1919-1922 culminated after the capture of Manisa by Kemalist forces in the murder of 40,000 Christian men, women and children of Ottoman citizenship from the cities of Smyrna and Manisa, and finally in the burning of the Christian quarters of Smyrna.

Most of the Christian deportees from Smyrna and Manisa “were driven toward Magnesia [Manisa] and beyond. Many were killed in a deep canyon along the Magnesia Road called Buyuk [Büyük – ‘large’] Dere. Many Greeks were reportedly killed in the march (…). Ioannis D. Kostikdakis, an Ottoman Greek from Kata Panogia [Kato Panagia], who survived, wrote, ‘As we arrived at the entrance of the gorge, a stifling stench hampered our breathing… Thousands of corpses, men, women, children, swollen from decay, filled the endless ravine.’[7] (…) In an interview collected by the Asia Minor Research Center in its book Exodus, Anastassis Haranis, an Ottoman Greek from a village near Phocaea [Phokaia, Foça], said, ‘In Bunarbassi [Bunarbaşı, near Smyrna], after they had stolen everything from us, they delivered us to new guards. During the night they led us through the ravine of Sypilos (a mountain near Magnesia) where they searched us again and took all our money. Turkish men and women came to the road while we passed, and they kept saying to our guards: ‘If we give a two Turkish lira, will you give us one Giaur (infidel)?’ The guards ruthlessly gave over the people, and these [the villagers] killed them.’”[8] The sale of Greek Ottoman deported civilians to the local Muslim population, who satisfied their desire for revenge on the defenseless victims, is also confirmed in the memoir of the Ayvalik-born Greek Ottoman author and genocide survivor Elias Venezis.

One of the first tasks of the forced labor battalion of E. Venezis in Manisa was to clear the area of these corpses, which had been tied to one another with wire, before they were killed and dumped in the huge ravine of Mount Sipylos, which Venezis called Kirtikdere. The corpses already had begun to disintegrate, and the water drove them to the ravine’s edge, “where they reached the road and railroad tracks”[9]. The Turkish authorities feared that the floating remnants of massive killings of Christians might be seen by the Spanish Nations League official Dellara, who was “appointed to examine the conditions of the prisoners and the ‘care’ that the Turkish government was providing them.”[10]