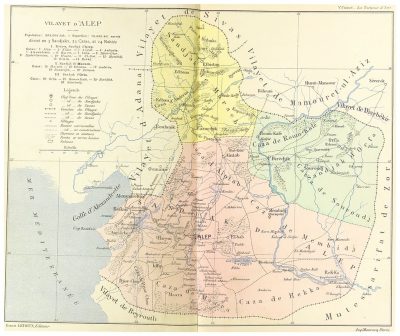

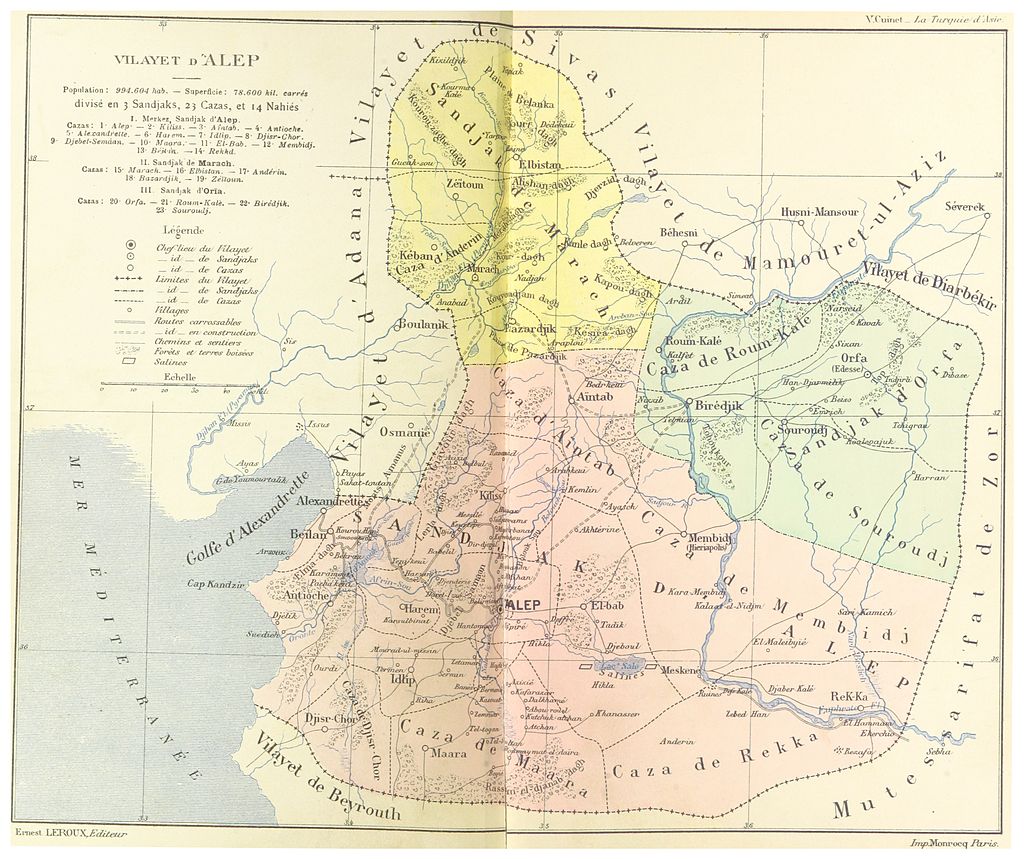

Administration

The vilayet was established in March 1866. It covered a territory of 78,490 km2, comprising around 1876 the six sancaks of 1) Aleppo (in 1908 the kazas of Ayintab [Trk.: Antep] and Pazarcık [Bazarcık] from the Maraş sancak were joined to a new sancak) with the kazas of Aleppo, İskenderun (Alexandretta), Antakya, Belen, Idlib, Al-Bab, Jisr al-Shughur, 2) Aintab (with the kazas of Gaziantep, Kilis, Rumkale), 3) Cebelisemaan (kazas Mount Simeon, Maarrat al-Nu’man, Manbij), 4) Maraş (kazas Maraş, Pazarcık, Elbistan, Zeytun, Göksun), 5) Urfa (kazas Urfa, Birecik, Nizip, Suruç, Harran, Raqqa (Rakka)), and 6) Zor (later an independent sancak) with the kazas Deir ez-Zor and Ras al-Ayn.[1] Around 1892, the number of sancaks was reduced to three: Aleppo, Urfa, and Maraş. Before the First World War, the vilayet Aleppo consisted of the five sancaks of Aleppo, Maraş, Ayntab (Antep), Urfa, and Antioch (Antakya).

History

The new boundaries of this administrative unit were stretched northward to include the largely Turkish-speaking cities of Maraş, Antep and Urfa giving the province a roughly equal number of Arabic- and Turkish-speakers, as well as a large Armenian-speaking minority.

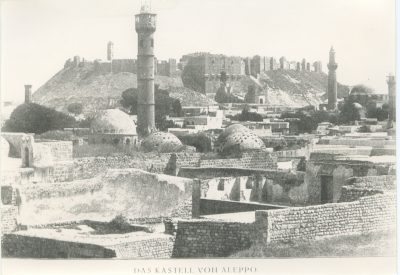

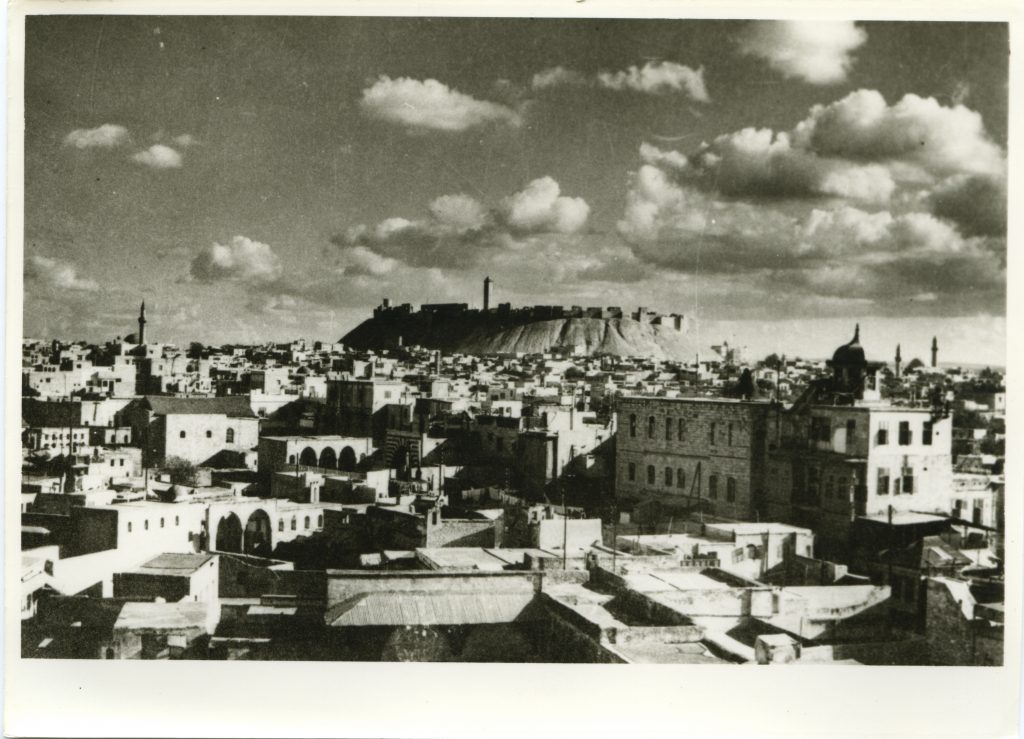

Thanks to its strategic geographic location on the trade route between Anatolia and the east, Aleppo rose to high prominence in the Ottoman era, at one point being second only to Constantinople in the empire. However, the economy of Aleppo was badly hit by the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, and since then Damascus rose as a serious competitor with Aleppo over the title of the capital of Syria.

Historically, Aleppo was more linked in economy and culture with its sister Anatolian cities than with Damascus.

At the end of World War I, the Treaty of Sèvres made most of the Province of Aleppo part of the newly established nation of Syria, while Cilicia was promised by France to become an Armenian state. However, Mustafa Kemal annexed most of the Province of Aleppo as well as Cilicia to Turkey in his War of Independence. The Arab residents in the province (as well as the Kurds) supported the Turks in this war against the French, a notable example being Ibrahim Hanano who directly coordinated with Kemal and received weaponry from him. The outcome, however, was disastrous for Aleppo, because as per the Treaty of Lausanne, most of the Province of Aleppo was made part of Turkey with the exception of Aleppo and Alexandretta; thus, Aleppo was cut from its northern satellites and from the Anatolian cities beyond on which Aleppo depended heavily in commerce. Moreover, the Sykes-Picot division of the Near East separated Aleppo from most of Mesopotamia, which also harmed the economy of Aleppo. The situation exacerbated further in 1939 when Alexandretta was annexed to Turkey, thus depriving Aleppo from its main port of İskenderun (Alexandretta) and leaving it in total isolation within Syria.

Population

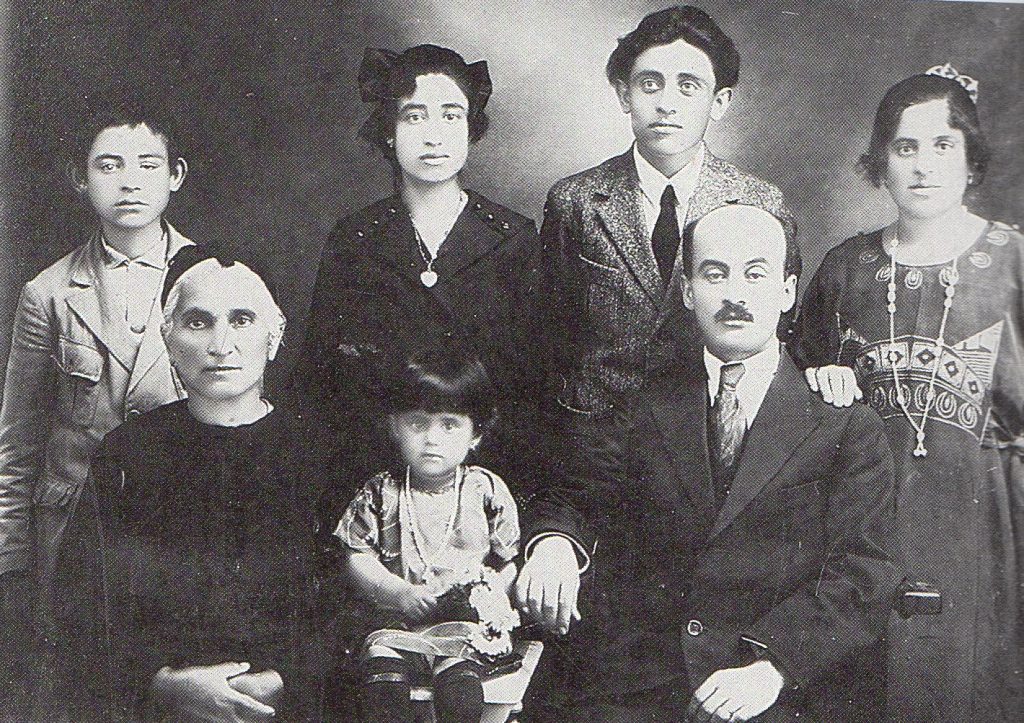

The preliminary results of the first Ottoman census of 1885 (published in 1908) gave the population of this province as 2,600,000.[2] According the the census of the Armenian Apostolic Patriarchate of Constantinople, there lived 189, 565 Armenians in the vilayet Aleppo before the First World War.[3] The Armenian presence in the northern Syrian capital of Aleppo dates back to the first century B.C., when the city belonged to the empire of Tigran the Great for fourteen years. During and after the First World War, Aleppo became a refuge for thousands of Armenian deportees and escapees from Anatolia.

Destruction

1915

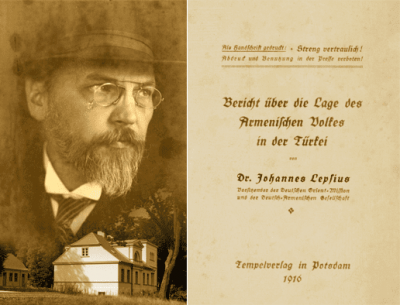

“In the Aleppo vilayet, massacres and further deportations were prevented until May [1915] by Vali Jelal Bey, who enjoyed the general confidence of Christians and Muhammadans. Thanks to him, as long as he was in office, there were no major deportations from the cities of his vilayet.

In conjunction with the Vali, the German consul in Aleppo, Mr. [Walter] Rößler, did his utmost to stop the action against the Armenians and to take measures to alleviate the hardship. From the Armenian side it is testified to him (in contrast to the completely unfounded allegations of the

English press) that he prevented a planned massacre by his visit to Marash and earned the thanks of the endangered and needy in every respect.

The Vali of Aleppo, Jelal Bey, who had not complied with the orders of the central government demanding the deportation of all the Armenians of the Vilayet, was transferred to Konia [Konya]. He was replaced by the former Vali of Van, Bekir Sami Bey. He then carried out the deportation of the towns and villages of the vilayet that had been spared.

The Armenian population of Marash was deported at the end of May, that of Aintab [Antep] at the end of July.” [4]

Aleppo Province as a Destruction Area

Although initially the deportation of the Armenian population of this province seems to have been not intended, especially within its coastal areas, the province became the center of the extermination of the Armenian population deported almost nationwide since spring 1915. The city of Aleppo was the seat of the authority that coordinated and realized the state policy of extermination: the Aleppo Sub-Directorate for Deportees. Aleppo’s suburbs were home to the transit camps for onward transport. “Fifty to 70 people in Aleppo were dying of typhus or typhoid fever every day, despite the efforts of the Armenian relief committee that had been formed under the leadership of Sarkis Jierjian in order to provide the deportees with basic necessities and medical care.”[5]

Despite massacres, exhaustion and starvation en route, about 870,000 Armenian deportees had arrived in the desert-like areas of Syria. Several concentration camps had been established near stations of the Baghdad railway that ran along the banks of the Euphrates. Living conditions were disastrous. In a very short period of six or seven months, tens of thousands perished from epidemics and starvation:

- in the concentration camp of Islahiye 60,000 (autumn 1915-early 1916),

- in the concentration camp of Mamoura about 40,000 (summer-autumn 1915),

- in the concentration camps of Radjo, Katma and Azaz about 60,000 (autumn 1915-spring 1916),

- in the concentration camps of Bab and Akhterim about 50-60,000 (October 1915-spring 1916),

- in the camp of Meskene (Maskanah) about 60,000 (November 1915-April 1916),

- in the camp of Dipsi about 30,000 (November 1915-April 1916).[6]

From spring 1916, a second phase of annihilation started: Most camps were ‘cleared’ by local death squads of the Special Organization (mostly ethnic Circassians, Chechens and local Arab tribes) who butchered the population of one camp after the other or suffocated and burnt tens of thousands alive in oil-rich cave systems such as Shaddadeh, which they set ablaze. In other cases, Armenians were driven into the interior of the desert region and left to a ‘natural’ death of starvation or typhus. The most notorious camps were those of Deir ez-Zor-Marat (192,000 victims during November 1915 – June 1916; 150,000 victims were slaughtered between Souvar and Shaddadeh) and Ras al-Ayn (about 14,000 victims; 30,000 more died from starvation and epidemics in nearby areas).

In all, 630,000 of the 870,000 deportees perished; of these victims, 200,000 died during massacres in the area of Ras al-Ayn and Deir ez-Zor.[7]

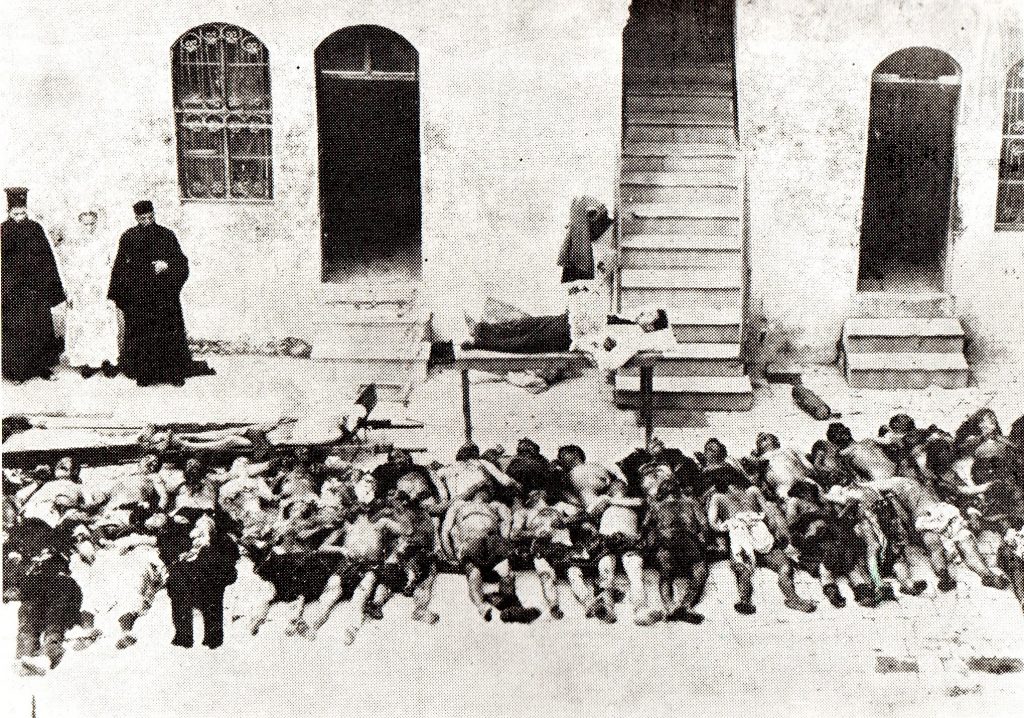

1919 (Under British administration)

“Muslim anger mounted in the first months of 1919, as the Allied-controlled government of Constantinople issued a stream of directives to local officials to restore Christian orphans and women to their communities, assist refugee return, and return stolen property. British troops managed to nip in the bud massacres planned in Antep and Maraş and at least partially disarmed the Antep Turks. The British punitively closed cafes, shops, and markets. They also exiled to Aleppo six of the town’s notables. But in Aleppo a massacre took place on February 28, at ‘Turkish instigation.’ Between forty-eight and eighty-three Armenian refugees were murdered and more than a hundred wounded. The attack was carried out ‘principally by Arab police and gendarmes.’ Intervention by British troops prevented higher casualties. The British later hanged three assailants, jailed others, and exiled fifteen to Sudan.”[8]