Toponym

The original Armenian name Khlat Խլաթ (Ottoman Turkish: اخلاط; Kurdish: Xelat; Medieval Greek: Χαλάτα – Chalata) is documented since the year 788. In ancient Armenian literature it was sometimes called Bznunyats city. The Turks usually call it Ahlat, a toponym, borrowed from the Arabs. According to the Arabic chronicler Ibn al-Asir, the city was called Akhlat (‘mixed’) ostensibly because its inhabitants were religiously and linguistically heterogeneous; they spoke Arabic, Persian, and Armenian.

Population

In 1891 the kaza of Khlat had 23,659 inhabitants, consisting of 16,635 were Muslims, 6,609 Armenians and 415 others. The French geographer Vital Cuinet estimated the population of Ahlat at the end of the 19th century at 23,700. According to him, seventy percent were Muslims, whereas the rest were Christians, mostly Armenians.

History

Khlat is one of the oldest settlements in Armenia, although the precise date of its foundation is unknown. At first it was mentioned as a settlement, and later it turned into a big city, which had its stronghold and was considered to be the largest port of Lake Van. Dozens of Armenian and foreign chroniclers provide a lot of information about Khlat. Aristakes Lastivertsi considered it one of the largest cities in Armenia in the 11th century, and in the words of the famous Arabic chronicler Yakut, Khlat was a “strong and famous city”, “endowed with all kinds of goods.” It is especially praised as a port and a strong fortress. The defensive wall of the city was usually called a large, towering, three-gate.

During the reign of the Arshakuni (1st to 5th centuries) and until the last quarter of the 8th century, Khlat belonged to the house of Bznuni and was the main city of the Bznunik canton. The town was taken by the Arabs during the reign of Caliph Uthman (r. 644–656). During the next four centuries, Ahlat was ruled by Arab governors, Armenian princes, and Arab emirs of the Qays tribe. In the early 8th century, Arab tribes settled in the region, and Ahlat became part of the Arab Kaysite principality. About 983, Ahlat was controlled by a Kurdish chief named ‘Bāḏ’ (in Armenian spelled as ‘Bat’; thereafter, Ahlat was associated with the Kurdish Marwanids (centered in Diyarbekir), which sprang from Bāḏ.

After the revolt against the Arab yoke in 773-775, when the Bznunis, along with a number of other Armenian ministerial houses, lost their political weight, the canton of Bznunik and its center Khlat passed to the Bagratuni of Taron in the late 8th century or early 9th century. During 890 – 914 it was completely liberated from the Arabs, and the old fortress was rebuilt. Around that time, along with many other cities in Armenia, the period of Khlat’s rise began. During a relatively short period of the 10th and 11th centuries, it became one of the largest and most populous cities in the country.

The development of Khlat was facilitated by being a port en route Arjesh (Trk.: Erciş) to Baghesh (Bitlis). In the first half of the 11th century, it became a major center of handicrafts and trade, with a population of tens of thousands. During those times the peace of the city is disturbed only once. In 997, Khlat was attacked by the Curopalates David III of Tao (Arm.: Tayk) with the aim of capturing it and annexing it to his vast power. However, his troops suffered a disgraceful defeat under the city walls and were forced to retreat empty-handed, partly because of David’s contemptuous treatment towards its Armenian population.

The political situation of Khlat had significant ups and downs in the 11-13th centuries. After the Byzantine Emperor Basileios II ceded the city to the Artsrunis in the year 1000, its development continued until the invasions of the Seljuk in the 1070s, when it was captured and destroyed by the latter.

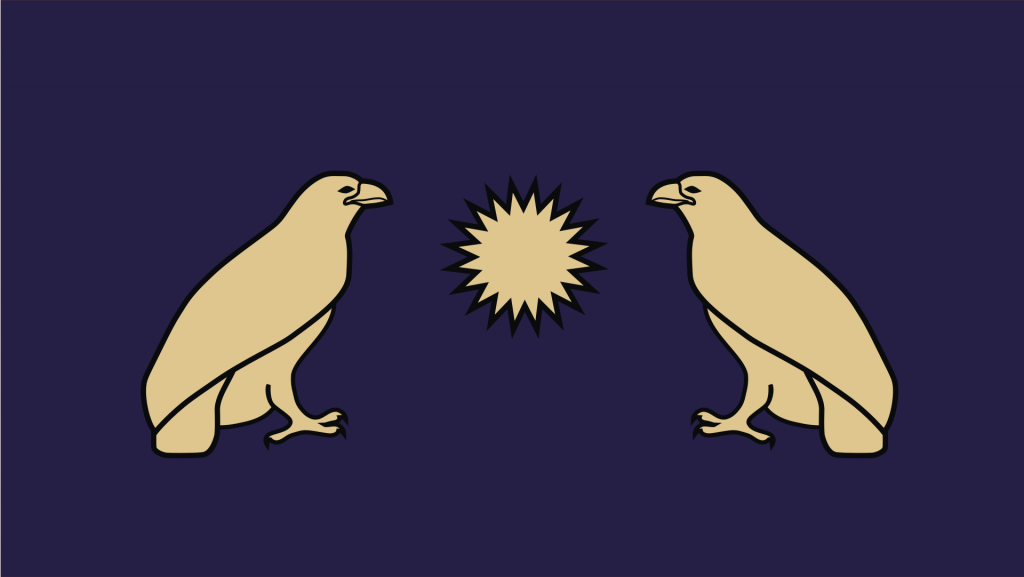

After the Battle of Manzikert (1071), the Seljuk army, led personally by Sultan Alp Arslan (r. 1063-1072), took possession of the town. The Seljuks then gave control over the town to the Turkmen slave commander Sökmen el-Kutbî (or al-Qutbi). Sökmen and his successors were known as the Shah-ı Armen (‘Armenian Rulers’, ‘rulers over Armenia’, or ‘Ahlat-Shahs’) and made Ahlat their capital. They ruled here until the 1330s, before the Mongol invasions. At the beginning of the 13th century, when Northern Armenia was liberated from the Seljuk yoke and a semi-independent, powerful government was formed there under the leadership of the Zakaryan princes, attempts were made by the same princes to liberate the central parts of the country, including Khlat and its environs. For this purpose, Zakare and Ivane Zakaryans, led by the Armenian-Georgian army in 1210, marched to the shores of Lake Van and to Khlat. However, the invasion of the Zakaryan brothers failed. Khlat again remained under the yoke of a foreigner, Ivane was captured by the sultan and released only after Zakare threatened. The fall of Khlat begins in the 1230s. Capturing Khlat in 1230, Jalaluddin subjected it to terrible destruction. The Mongol conquest of 1245 is no different from it, as a result of which the traces of the previous destruction have not yet been eliminated, the city is subjected to fire and sword. The devastation inflicted by the Mongols on Jalaluddin is compounded by the devastating earthquake of 1246, which destroyed most of the city’s structures, killing scores of people.

In the 16th and 15th centuries, the city was, in fact, once again a dull settlement, although chroniclers continued to call it a city by force of tradition. Khlat was one of the apples of discord during the long Turkish-Persian wars of the 16-17th centuries. Particularly severe were the battles between Shah Tahmasp I of Iran and Sultan Suleiman I (the Magnificient; the Lawgiver) in the 1540s, during which Khlat was devastated in 1548.

During Suleiman’s reign (1520-1566), Ahlat eventually became a solid part of the Ottoman Empire. However, Ahlat remained de facto under the control of various local Kurdish chiefs until the mid-19th century, when the central Ottoman government in Constantinople imposed direct rule on the town.

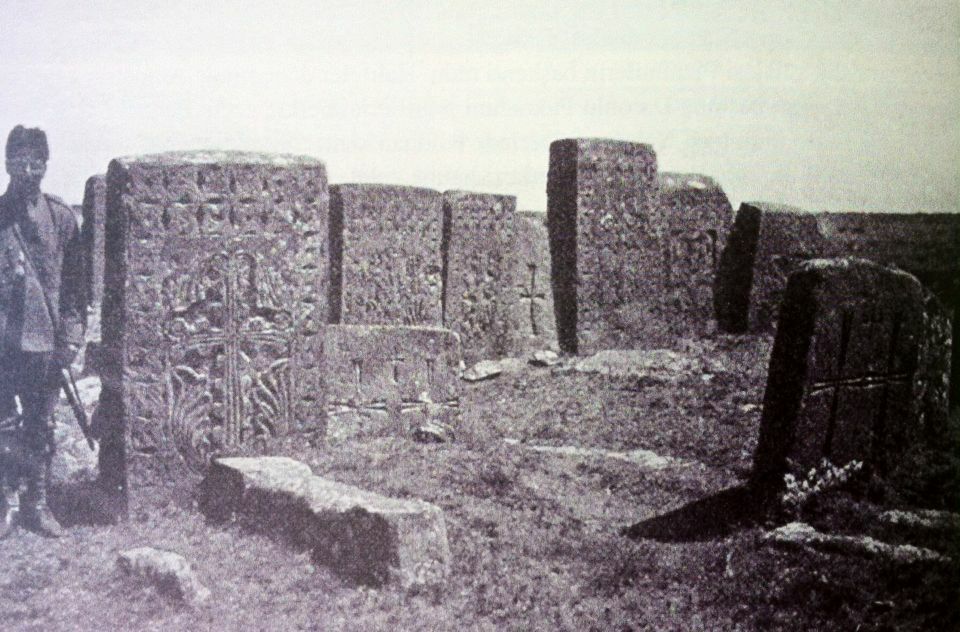

Among the historical monuments are the caves dug in the rocks near the city, several towers of the defensive wall on the seashore, the ruins of various buildings, which are mainly located in the district now called Kharaba şehir (“ruined city”). On the outskirts of the city is preserved a large cemetery from Arab times with huge tombstones with inscriptions.

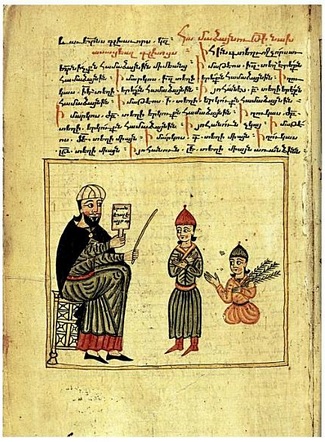

Apart from the fortress and its defensive structures, other monuments of Khlat deserve attention. Although Khlat since the 15th century presented a picture of decline, it remained a significant center of Armenian culture. Its school of writing is especially famous. We know more than 10 of the manuscripts copied here during the 15th century, among them three Bibles and two gospels. The pen of the priest Karapet, who worked in the first half of the 15th century, was especially famous. Grigor Khlatetsi (1349-1425) was born in Khlat. He is one of the prominent figures of Armenian culture: a chronicler, pedagogue, poet, musician, public figure.

Ahlat Town

In the Ottoman census of 1556, the town of Ahlat appears to be mixed Islamic-Armenian, three of the villages were Islamic and the others non-Muslim. When Vital Cuinet passed through the city in the late 19th century, ancient Ahlat was considered to be ‘abandoned’, and was referred to as Kharaba Şehir, i.e. ‘the ruined town’. At the beginning of the 20th century, there were 200 houses in Ahlat, of which only 15 were Armenian. The Armenian population generally disappeared during the years of the Ottoman genocide of the First World War.

Today, the population consists mainly of Turks, with Kurds and Circassians as a minority. 72 families of Meskhetian origin and brought from Ukraine were resettled in Üzümlü, in a certain neighborhood.[1]

“Between the old fortress and the ‘sea’ (Lake Van) stretches a large Mohammedan churchyard. This has found more favor than the dwellings of the living, and one cannot help feeling a peculiar sensation when, amidst all the ruins, one finds the graves intact. In reality, nothing is left of Akhlat but the graves.

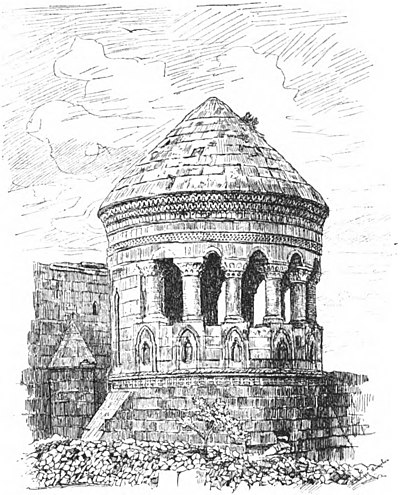

First of all, here is the great cemetery of the people; the tombstones, more than two meters high, covered throughout with beautiful inscriptions, show a strange correspondence; here is found the character of Akhlat’s history: namely, a great flourishing in a short period. In the midst of these tombs are found two tombs (türbes).

The most beautiful tombs are found on the path to Adilcevaz. The tomb of Sultan Bayandur (one of the Tatar chiefs who seized Akhlat in the fifteenth century) is a real jewel box. In front of a building with strict forms, built on a rectangular base, rises a cylindrical house, almost completely pierced. Elegant columns support capitals with short calyxes, at the ends of which runs an extremely finely worked cornice. The cottage is crowned with a conical stone roof. Over time, this reddish-brown, fine-grained stone has taken on warmer hues, wonderfully enhancing the overall beauty of the work.”Excerpted from: Paul Müller-Simonis: Vom Kaukasus zum Persischen Meerbusen: Druch Armenien, Kurdistan und Mesopotamien. Main: Verlag von Franz Kirchheim, 1897, p. 217 f.