Administration

The sancak comprised nine kazas.

Population

The sancak “boasted the 18 Armenian communities of Kastamonu town (653 Armenians / 140 households); Kadinsaray (pop. 154 / 35 households), Mururig (pop. 35 / 6 households), Kurucik (pop. 800 / 130 households), Daday (pop. 208 / 40 households), Geritzköy (pop. 102 / 20 households), Karabüyük (pop. 238 / 45 households), Devrekianu (pop. 183 / 38 households), Taşköprü (1,250 / 250 households), and the surrounding villages, Çuruş (pop. 33 / 6 households), Belençay (pop. 95 / 18 households), Gücüksu (pop. 79 / 16 households), Iregül ( pop. 91/ 17 households), Malahköy (pop. 77 / 14 households), Ğaracı (pop. 97 / 18 households), and Yumacik (pop. 99 / 18 households).” [1]

According to D. Ikonomidis’ reports, there lived 89,500 Muslims (Turks and Chapnis), 10,500 Circassians, 23,000 Greek Orthodox Christians and 300 Armenians in the sancak of Kastamonu.[2]

Destruction

In a report to the Imperial Embassy of Constantinople, the Russian vice-consul in Samsun described the situation in summer 1914 in bleak colors.

“The persecution of Christians is continuing in both this area and the Empire in general. A few days ago, a group of local Greek family men were sent to Taşköprü [sancak of Kastmonu] as laborers, for the construction of the Boyabat-Kastamonu road. The local Christian families of the city are in a sorry state.”[3]

On 16 July 1916, the German vice-consul in Samsun, Kuckhoff, informed the German Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Berlin that he had, “valid information that the entire Greek population of Sinope and the coast of Kastamoni province have been sent into exile. According to the Turks, exile equals extermination, because even those who escape being murdered will die, mostly of disease and starvation.”[4]

“On 15 March 1917, in a new and thorough report to the Ecumenical Patriarch, Metropolitan Germanos lodged yet another complaint about the repeated atrocities committed by local authorities and the plundering and displacement of Greeks living in the lowlands, where there were no guerrillas or deserters: ‘Nothing out of order ever took place there’. Most horrible of all was that: ‘Two thirds of the displaced population has already died in the Turkish villages of Ankara; the remaining third is declining, withering like a plant, and will have disappeared from the face of the earth in a matter of weeks. Christians from the Tripolis and Kerasus [Giresun] regions displaced to the vilayet of Sevastia [Sivas], and Christians from Sinope and Inepolis [Inebolu] displaced to the vilayet of Kastamonu shared the same fate. This is how an ancient civilization was annihilated, as well as a hard-working, honest, diligent people, because they had committed the ultimate sin of not being born Turks, but Greeks and Christians.’”[5]

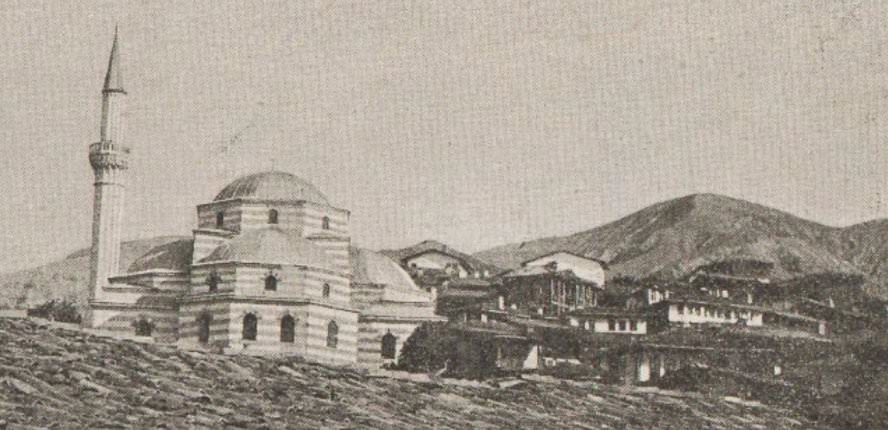

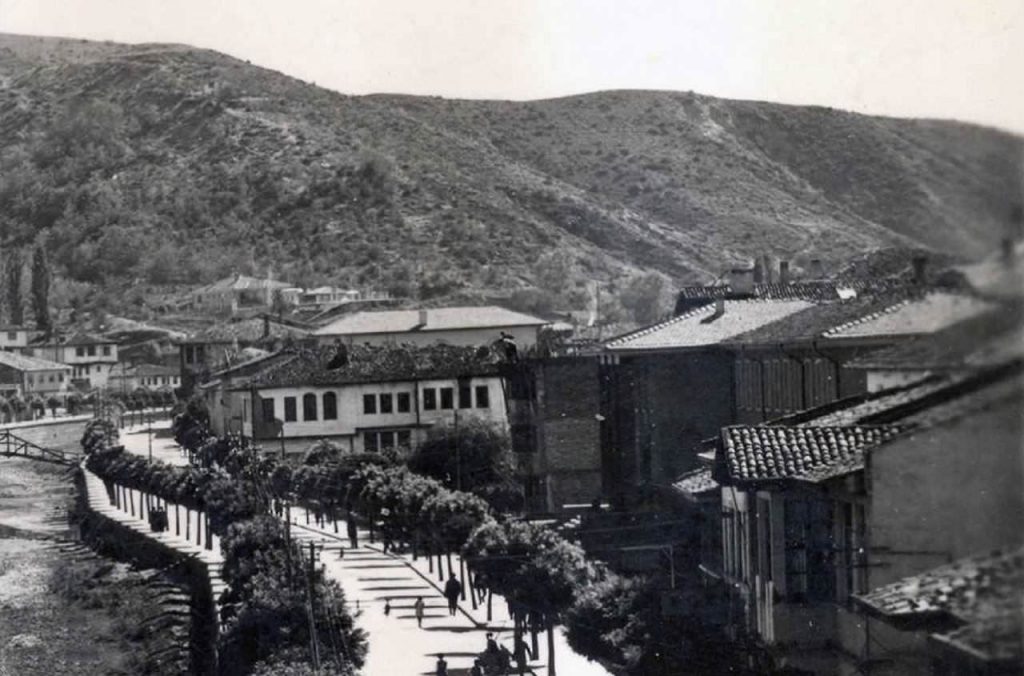

City of Kastamonu

The city is believed to have been founded in the 18th century B.C. It is located at the base of a mountain at which a Byzantine fortress existed. Manuel Erotikos Komnenos, a prominent general and the father of the Byzantine emperor Isaac I Komnenos, was given lands around Kastamonu by Emperor Basil II and built a fortress there named Kastra Komnenon (Κάστρα Κομνηνῶν). Manuel came to the notice of Basil II because of his defence, in 978, of Nicaea against the rebel Bardas Skleros.

Kastamonu was captured by the Ottoman Turks in 1393, was taken by Timur in 1403, and was regained by the Ottomans in 1460.

Population

Prior to 1923 and the forcible exchange of populations, Kastamoni had a population of 1,800 Greeks[6] and 653 Armenians (140 households).[7]