Toponym

The Syriac place-name ‘Ma’ṣartā’ (‘Ma’asarto’; Western Syriac pronunciation: Ma’asarte; Trk.: Maserte) means ‘wine press’. It is later mentioned by Theophylact Simocatta and George of Cyprus as Matzaron (Grk.: Ματζάρων, Latin: Mazarorum).

The present name Ömerli (introduced in 1960) is derived from the name of the Mhallami tribe Ömeryan.

Population

Maserte / Ma’asarte today is „a district town 20 kilometers northeast of Mardin on the border of the Mhallami (Muhallemi) area. Here lived 300 Syriac Orthodox Christians with a parish church, Mar Gewergis [Trk., Arab: Circis]. (…) They were known for the cultivation of grapes and weaving of wool.”[1]

As of 2013, three Syriac families reside in Maserte. The population of Maserte/Ömerli is Arabic-speaking.

History

It is unclear when Maserte was founded. The oldest traces date back to Assyrian times. Maserte is identified as the town of Madaranzu in Bit-Zamani, which was conquered by Ashurnasirpal II, King of Assyria, in 879 B.C. The town was likely captured by a Sasanian army in 573 at the time of the siege of Dara, during the Roman-Sasanian War of 572-591, but was retaken and the fort was restored by the Roman commanders Theodore and Andrew in 587.

Throughout history, many Syriac-Aramaic speaking Christians lived there, including Syriac Orthodox, Chaldean Catholics and Nestorians; the latter are said to have converted to Islam in the 14th century. Maserte was part of the Syriac Orthodox diocese of the Monastery of Saint Abai (Classical Syriac: ܕܝܪܐ ܕܡܪܝ ܐܒܝ, romanized: Dayro d-Mor Abay) until the death of its last bishop Isḥoq Ṣaliba in 1730, upon which the diocese was subsumed into the diocese of Mardin.

Destruction

„On June 12, 1915, a few men escaped from here and told the following story: Huseyin Bakkero, the owner of the village, went to Mardin and parleyed with the Kurdish tribal leaders Faris Chelebi [Çelebi], Mohammed Ali Chelebi, and the Dashit Chief Ahakat, to get participation in the liquidation of the Christians. Huseyin rode back and summoned the villagers and gave a solemn promise that they would come to no harm. However, when they arrived in his house, they were taken captive by a large number of Kurds. They were tied together and murdered, and their bodies were thrown into wells. Qarabash gave the date as June 2, 1915, [Pater Hyacinthe] Simon recorded that 80 Christians were killed. Two men saved themselves by hiding in a cave, and one arrived at Za’faran monastery. Some of the Muslim women protected the Christian women and children and escorted them, after a few days of hiding, to the Church of the Martyrs in Mardin.”

Excerpted from: Gaunt, David: Massacres, Resistance, Protectors: Muslim-Christian Relations in Eastern Anatolia During World War I. Piscataway: Gorgias Press, 2006, p. 238 f.

Amill Gorgis: An invitation to remember

With the histories of my parents and grandparents I would like to illustrate the horrible events in the southeast of Turkey around the year 1915. Until today such narratives are told differently by the descendants of the victims and the perpetrators.

The descendants of the victims carry this part of history with them as a trauma, filled with the fear that the events of that time could be repeated. The descendants of the perpetrators, on the other hand, regard the events as war-related. They do not exclude the possibility that innocent people were harmed in the process. But in any case, there is a feeling of triumph over those who have been eliminated. In this contribution I would like to take up a case from the year 2000 in order to describe the kind of dispute between the descendants of perpetrators and victims with regard to the events of 1915 in the Ottoman Empire. In doing so, I cannot suppress my personal consternation. The history of my parents and grandparents is a constant reminder to me of a people who were persecuted, tortured, expelled and murdered.

An example of conflicting perceptions

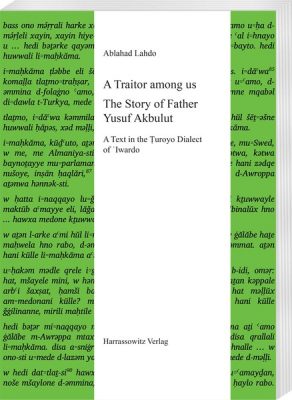

Syriac (Aramaic) Christians read with horror the report in the Turkish daily newspaper Hürriyet of 4 October 2000 about a Syriac Orthodox priest from the city of Diyarbakir. The headline read: ‘A traitor among us’. Below it was a photo of the clergyman raising the cross for blessing, and next to the picture was a reproduction of an interview in which he takes a stand on the genocide against Armenians and Syriac (Aramaic) Christians at the beginning of the 20th century. What crime was this clergyman guilty of? He has spoken honestly about his experience with this issue. He has told about the events of that time as told to him by his parents, relatives and contemporary witnesses.

There is hardly a family of Syriac (Aramaic) Christians from the tribal area in southeastern Turkey that was not affected by this first cruel and brutal persecution of the 20th century. Every Syriac (Aramaic) Christian of my generation knows about the harsh fate of persecution and expulsion of their parents and grandparents.

We have heard about the fate of our grandparents, although many of us grew up without grandparents. It is, I think, something natural to ask about them and why they are no longer alive. I grew up in Syria in a small town where extraordinary events were very rare. For us children, visits to befriended families and relatives were special because they brought a change to our monotonous daily routine. During these mutual visits, our parents told each other stories about the time when they lived in Turkey. All of them had fled Turkey at some point because of that persecution and fear of having to experience something similar again. We, the children, listened to the stories, although there was much that we did not understand. The adults, however, told us over and over again about the Ferman, the Sultan’s decree, and about the Time of the Sword (Sayfo). The more we grew older, the more we understood about what had happened to the Christians under Ottoman rule in 1915. Even though we could not grasp all the narratives about that time, one thing became clear to us: Our grandparents were persecuted and killed for their faith solely. And because, according to the ideology of the ruling Young Turks, as a Christian ethnic group they could not be integrated into the Turkish nation-state that was to be created, and because they were considered incapable of assimilation and unwilling to assimilate. Those few who converted to Islam under threat of death were spared, but all those who clung to their ancestral faith experienced every humiliation and persecution up to and including murder.

The fate of my parents and grandparents as an example

I was, of course, particularly interested in the history of my own grandparents. I admired their courage and was proud of them in the knowledge that the Christian faith meant so much to them that they were willing to sacrifice their lives for the sake of that faith. My father, George Gabriel Gorgis, described them as proud and prosperous people according to the stories of his relatives who escaped the massacre. My grandparents, Gabriel and Manzoura Gorgis, received news the day before they were attacked and murdered that an imminent attack on the Christians of the village of Ma’asarte was imminent. Because the situation in 1915 was such that they could expect an attack any day. That is why they took the precaution of placing their children with their grandmother in Mardin, so that my grandparents would be able to defend themselves and escape in case of emergency. However, George and Manzoura Gorgis were not attacked, but lured into a trap and murdered along with many other Christians from Ma’asarte, without any possibility of self-defense.

The survivor and Catholic cleric Isḥāq Armale wrote the following about this in his book The Worst of Calamities for Christians:

“Maʿasarte is a village in the northeast. In it lived 800 schismatic [i.e., Orthodox] Syriacs. They worked in the vineyards and wove sacks. In the middle of June 1915, three men fled from there to Binēbīl, then to Dayr az-Zaʿfarān, where they told the Christians what had happened to them: The sheikh of Maʿasarte, Husayn Bakrō, came to Mardin to seek advice from the city’s prominent figures on what to do with the Christians. Their answer was to exterminate them completely. He returned with the decision to exterminate them. Arriving in the city, he had the Christians come to him to promise them, as was customary, that they would be safe. When the Christians went to his house, they saw that it was crowded with thuggish Kurds. As soon as the Christians entered the front yard, they were attacked and tied up. Their wives and all the children were led together to the nearby wells, relentlessly beaten and massacred, and their corpses were thrown into the wells. Malkē Yaʿqūb, Yaʿqūb, and the latter’s brother hid in a cave, where they stayed for three days, then fled to Binēbīl, then to Dayr az-Zaʿfarān. The Kurds took all their personal belongings, land and property, and were satisfied.”

The wells in Ma’asarte mentioned by Armale are still called ‘Jub al-Nasara’ (Well of the Christians). In September 2014, I visited Ma’asarte, now Ömerli, with my daughter. We met an old man and his son who run a blacksmith’s workshop in what is now a small town. When asked if the wells still existed, the elderly man referred to a well in the town. This had been cleansed of the bones of the genocide victims a year earlier. The current owner of the land on which the well is located is responsible for this. He reported that the skeletons’ dentures were intact. This indicates that the beheaded must have been relatively young.

My father, who was seven years old in the Year of the Sword, was hiding with his brother, who was two years older than he, at their grandmother’s house, and so they were saved. My uncle, Elias Gabriel Gorgis, stayed with his grandmother for a few months until she passed away. She was old and left on her own, and there was no one to take care of her anymore. Thus, she died of exhaustion and lack of food. The little she was able to raise by working and begging, she had to share with her grandson. Although my father was a child, he recognized the situation of his grandmother Katto and sought refuge in Al Zafaran Monastery, where he could stay only a few months, because the monastery was overcrowded with refugees and was therefore unable to provide for all of them.

At that time, there were some Christians who had survived the carnage and organized their escape to Syria or Lebanon. Some continued to emigrate from there to South and North America. My father joined a group that went to Syria. His older brother also managed to escape to Syria. There they built a new existence for themselves. I leave it to the imagination of the reader to imagine what such children had to go through until they grew up and could stand on their own two feet without a relative to guide them through life. It is a miracle that these orphans created a family and took responsibility in community life. The spirit and faith of their martyred parents must have accompanied them so that they were not thrown off course. What I describe here for my parents is just as true for all Syriac (Aramaic) speaking Christians in my small town, and also almost everywhere where they settled as refugees. They all shared the same fate and knew they were united in their fated community. They built churches and founded schools that were accessible not only to Christian children but also to their Muslim neighbors.

I asked my mother, Marin Habib al-Khaief, a lot about that time when I was a child. My mother was a simple, plain and God-fearing woman. She raised us children with a lot of love, care and self-sacrifice. The more I think about it, the more I get the feeling that she made an effort to give us children the love and protection that she herself had to do without in her childhood. I kept asking her about her parents. My mother was from Mardin. She could not satisfy my curiosity, because what she knew about her parents she had learned from her aunt. She herself was just one and a half years old when her father Habib was sent to forced labor with a convoy to build roads for the Ottoman Empire. He and his comrades were used as forced laborers there and worn down to exhaustion: When they were no longer fit for hard labor, they were disposed of. Their father did not return and died under the burden of forced labor. His body was covered with earth at the side of the road, as was common for workers who had been maltreated to death. Her mother, Helane, became ill afterwards. This was probably due to grief over the loss of her husband and because she was unprepared to stand alone with two children to feed while war, famine, murder, and displacement prevailed. It was not long before the mother of my mother was also dead.

My mother and her older brother were placed in the care of their aunt, their mother’s sister. I remember my mother’s sighing to this day when she talked about it. She spoke of it without harboring any feeling of hatred toward the authors of such circumstances, toward those who took her father away from her and were to blame for her mother collapsing under the weight of her responsibilities and dying so young. My mother’s thoughts were of the memory of those who had to experience so much suffering and hardship, and not of those who inflicted so much misery and evil on others. She spoke very fondly of her aunt, who also stood alone with her four children, a hardworking and courageous woman who nevertheless did not hesitate to take in her nephew and niece and care for them along with her other children.

Due to economic hardship, my mother’s brother, with the consent of his aunt, decided to leave Mardin and move with a caravan to Lebanon to be placed in an orphanage and attend school. She has not heard from her brother since. Years later, when my parents’ economic situation allowed it, we made inquiries from Syria, unfortunately without success, and so my mother could not know until her death whether her brother ever arrived in Lebanon. This uncertainty weighed heavily on her.

Although her aunt had a very arduous time herself, my mother was not left behind in this family. As a child, she was able to attend a school in Mardin and a weaving shop run by a female missionary. She called this missionary ‘Miss Felanga’. My mother’s school days will have been short, for she had not retained much of them.

When I asked her about it, she replied that the time was very short indeed. Soon she was to move to relatives in Syria, where she then married my father at a very young age.

Many, almost every family of Christians from our region shares this fate or even worse. What Father Iosif Akbulut expressed in his interview with ‘Hürriyet’ thus represents nothing else than the general history of Syriac Christians at the beginning of the 20th century. But to deny this part of the history of one’s own family and people means to want to erase the memory of these people. What is not remembered never existed? No, we cannot and will not comply with such a demand.

On the current discussion of history

The suffering inflicted in 1915 traumatizes us to this day. We are shocked that the historical reality in Turkey is still not allowed to be called by its name. And who speaks the truth, is still punished for it! Through this denial, we are burdened with suffering for the second time. This hurts. The vehemence with which those responsible for politics and the media in Turkey ignore this part of our common history is depressing, disconcerting and unsettling for us.

We are all the more grateful for those Turkish human rights defenders and scholars who for about 30 years have been increasingly speaking out and openly addressing the issue of the extermination of indigenous Christians in the Ottoman Empire. They do this, although they know that they have to expect harsh reprisals, criminal prosecution, long prison sentences or permanent exile. Quite a few ended up in prison for several years. The courageous, principled commitment of Turkish human rights activists creates a sense of closeness and inspires confidence.

Conversely, we are saddened and dismayed by the dismissive and arrogant attitude of those who bear responsibility in Turkey towards their responsibility for the past in this matter. However, it is important for Turkey to take the fate of Syriac Orthodox Christians seriously and to ensure that Syriac (Aramaic) Christians can live in Turkey without fear, even if they do not want to deny their own history and the fate of their ancestors.

The annihilation of Ottoman Christians before, during, and after World War I, let alone accepting historical responsibility, was and is not an issue, neither for politicians nor for most of the country’s intellectuals. And if historians deal with it at all, it is usually not to investigate the suffering of Christians during that dark period, but rather to prove Turkey’s innocence.

The Swiss scholar Hans-Lukas Kieser writes in his dissertation ‘The Missed Peace’: ‘A highly erudite professor like Mim Kemâl Öke, who enjoyed relatively wide latitude at the Atatürk Ilkeleri ve Inkilâp Tarihi Enstitüsü of Bogaziçi University in Istanbul, places his study of the Armenian Question during and after World War I entirely at the service of the long-standing Young Turk assertion that the ‘resettlement’ of Armenians was a wartime necessity and that its implementation was motivated by humanitarian concern – as if, contrary to the long list of sources he lists at the end of his work, he had read only the pronouncements of the Ministry of Interior at the time.’

It is astonishing, how little information altogether is provided about the history of the Christians in Turkey. Which national in Turkey still knows today that more than one hundred years ago scarcely twenty per cent of the inhabitants of Turkey were Christians? Today they make only 0.03% percent of the population! The metropolis of Istanbul had a million inhabitants over a hundred years ago, of which 350,000 were Greeks and 100,000 Armenians. So almost half of the city’s inhabitants were Christians. Today Istanbul has 15 million inhabitants, of which merely 60,000 are Christians of various denominations. Who knows that in the middle of the 19th century the city of Diyarbakir had 7500 families, 35% of which were Christians? Today the city has about 1.5 million inhabitants, and only seven of them are Christian families of different denominations.

In the city of Mardin in the middle of the 19th century there were 700 Syriac Orthodox families, 200 Syriac Catholic, 500 Armenian Catholic, 60-70 Chaldean Christians. There were eight churches of different Christian denominations. Today there are no more than 25 Christian families living in the city. They are served by a Syriac Orthodox priest. There were 100 Christian families living in Nusaybin, today there is not a single one.

With the scattering of the inhabitants in the eastern border regions through migration, flight, deportation and murder, a fragile social structure has fallen apart. It is staggering that this process involved the systematic, even physical, elimination of a significant social element. It is also disastrous that the exercise of such violence is justified in triumphalist terms, thus preparing the ground for further acts of violence.

It is important for Turkey to acknowledge and value the Syriac (Aramaic) Christians and their rich scholarly and cultural heritage with numerous monasteries and churches that they have produced on the soil of today’s Turkey. People in Turkey must learn that the legacy of Syriac (Aramaic) Christians dating back two millennia is also a part of contemporary Turkey to be proud of. The Syriac (Aramaic) Christians have never been and will never be against Turkey. The welfare of this country serves the welfare of all who live in it. Peace and stability thrive where people recognize each other’s diversity, and it is one of the most basic human rights to appreciate a people who have lived with their own cultural and religious imprint for centuries.

Not the feeling of triumph over the fact that de facto no more non-Turkish ethnic groups exist in Turkey should prevail, but consternation over the fact that so much diversity and wealth of religiousness and cultural identity has been lost.

It is more necessary than ever, in order to reduce hatred, blind fanaticism and prejudice in this globalized world of ours, to strengthen the dialogue between the different religious and cultural communities. But this is a dialogue that must be conducted on an equal footing, a dialogue in which existential questions of an entire people and a religious community can be raised without fear of being arrested, as happened in the case of Pastor Akbulut. Father Akbulut would not have been released without the solidarity of the Western world.

We wonder how Turkey can become a member of the EU with this attitude and support the EU’s humanistic ideals, if it does not tolerate any discussion about this part of history, which was and is so painful for many Christians from Turkey?

Closing Remark

We invite to remember the indigenous Christians in the Ottoman Empire – not to accuse, but to restore the dignity of the victims and as a reminder to forestall future such crimes. We want to remember those who were victims of religious and national fanaticism and to look towards a future in which all people are respected, each with their own history and distinctiveness. It is an appeal to work everywhere in the world for a society in which diversity is perceived as richness and in which no one has the right to erase minorities and deny their history.