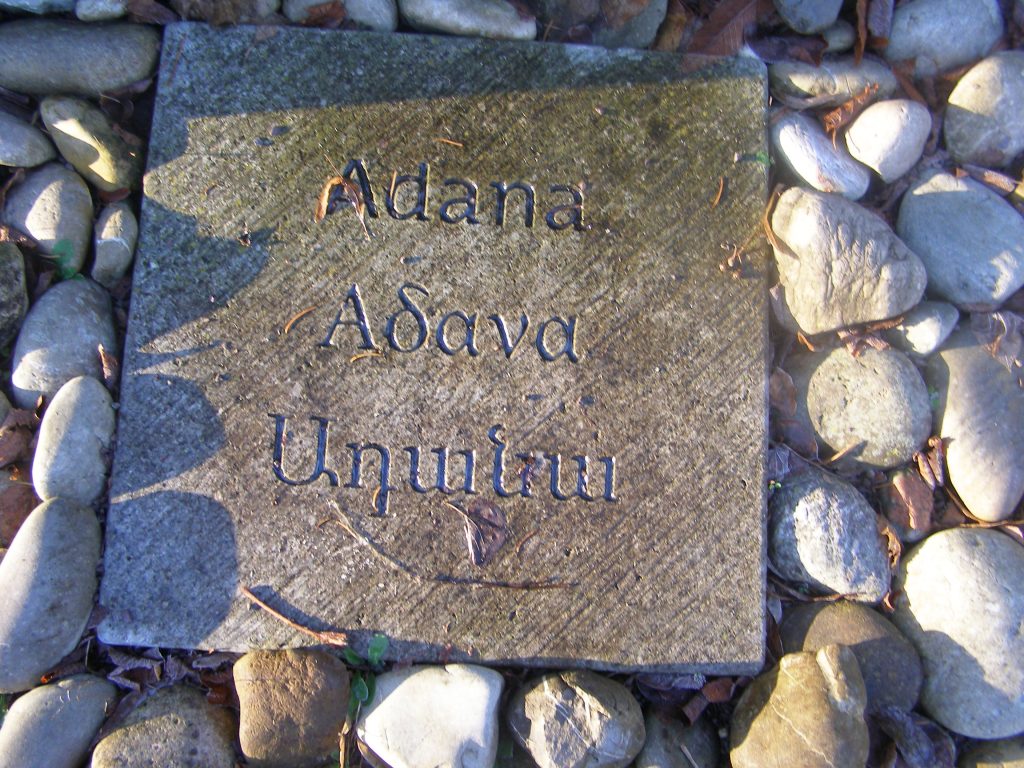

Toponym

In Homer‘s Illiad, the name of the city is mentioned as Adana. For a short while during the Hellenistic era, the city was known as Ἀντιόχεια τῆς Κιλικίας (Antiocheia in Cilicia) and as Ἀντιόχεια ἡ πρὸς Σάρον (Antiocheia on Sarus). On some cuneiforms, the city name was mentioned as Quwê, and as Coa in some other sources which could be the place Solomon had obtained his horses as per Bible (I Kings 10:28; II Chronicles 1:16).

Under Armenian rule, the city was known as Ատանա (Atana) or Ադանա (Adana).

An ancient Greco-Roman legend mentions that the name of Adana originates from Adanus, the son of the Greek god Uranus, who founded the city next to the river with his brother. His brother’s name, Sarus, was given to the river. An older legend, in Accadian, Sumerian, Babylonian, Assyrian and Hittite mythologies, the city’s name derives from the Storm and rain god Adad who lived in the surrounding forests. There are Hittite manuscripts that were founded in the region regarding this legend. The legend had survived as the Storm and rain god continued to create rain and abundance. The locals had great admiration towards the God and called the region Uru Adaniyya (Adana region) in his honor. The city inhabitants were called Danuna.

Armenian Population

Armenian villages around Adana were Sheikh-Murad, Hay Gyugh (‘Armenian Village’), Abdoglu, Kozoluk and others.

History

First known people living in Adana and the surrounding area were the Luwians. They controlled the Mediterranean coasts of Anatolia roughly from 3000 B.C. to around 1600 B.C. Hittites took over the region which came to be known as Kizzuwatna. Inhabited by Luwians and Hurrians, Kizzuwatna had an autonomous governance under the Hittites protection, but they had a brief independent period from the 1500s to 1420s. According to the Hittite inscription of Kava, found in Hattusa (Boğazkale), Kizzuwatna was the kingdom that ruled Adana, under the protection of the Hittites by 1335 B.C. Beginning with the collapse of the Hittite Empire c. 1191–1189 B.C., Adana native Denyen sea peoples took control of the plain until around 900 B.C. Neo-Hittite States founded in the region then after and Quwê state was centered around Adana. Quwê and other states were protected by the Neo-Assyrian Empire, though they had independent periods. After the Greek migration to Cilicia in the 8th century B.C., the region was unified under the rule of Mopsos dynasty and Adana was established as the capital. Bilingual inscriptions of the ninth and eighth centuries found in Mopsuestia were written in hieroglyphic Luwian and Phoenician. Assyrians took control of the regions several times until their collapse in 612 B.C.

Cilicians founded the Kingdom of Cilicia in 612 B.C. with the efforts of Syennesis I. The kingdom was independent until the invasion of Achaemenid Empire in 549 BC, then after, became an autonomous satrapy of Achaemenids until 401 BC. The uncertain loyalty of the Syennessis during the rebellion of Cyrus the Younger led Artaxerxes II to abolish the Syennesis administration and replace it with a centrally appointed satrap. Archeological remains of a procession reveals the existence of Persian nobility in Adana.

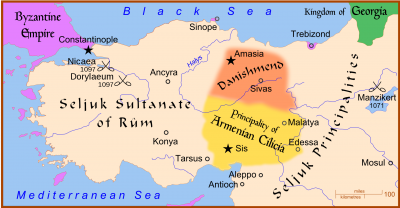

Alexander had an unexpected entry into Cilicia in 333 B.C. through the Cilician Gates and appointed the Syennesis dynasty to re-administer the region. His death in 323 B.C. marked the beginning of the Hellenistic era, as Greek replaced Luwian as the language of the region. After a short time under the Ptolemaic dominion, Seleucid Empire took control of the region in 312 BC. Adanan locals had adopted a Greek name for the city, Antiocheia on Saron, to demonstrate loyalty to the Seleucid dynasty. The adopted name and the motifs illustrating the personification of the city seated above the river-god Sarus on city’s minted coins, reveal appreciation to the rivers which were strong part of the Cilician identity. Although the Adana area were into international trade, coasts of rugged Cilicia were under the heavy plunder of the Cilician pirates. Seleucids ruled Adana for more than two centuries until weakened by the civil war which led them to offer allegiance to Tigranes II, the King of Armenia who conquered a vast region in the Levant. Cilicia became a vassal state of the Kingdom of Armenia in 83 BC and new settlements were founded by Armenians in the region.

Roman-Byzantine, Islamic and Armenian era

Pompey took over entire Cilicia and organized it as a Roman province in 64BC. Adana was of relatively minor importance during the Roman‘s influential period, while nearby Tarsus was the metropolis of the area. During the era of Pompey, the city was used as a prison for the pirates of Cilicia. The Sarus bridge was built in the early 2nd century, and for several centuries thereafter, the city was a waystation on a Roman military road leading to the East. After the permanent split of the Roman Empire in 395 AD, the area became a part of the Byzantine Empire, and was probably developed during the time of Julian the Apostate. With the construction of large bridges, roads, government buildings, irrigation and plantation, Adana and Cilicia became the most developed and important trade centers of the region.

Adana was a Christian bishopric, a suffragan of the metropolitan see of Tarsus, but was raised to the rank of autocephalous archdiocese after 680, the year in which its bishop appeared as a simple bishop at the Third Council of Constantinople, but before its listing in a 10th-century Notitiae Episcopatuum as an archdiocese. The Bishop Paulinus participated in the First Council of Nicaea in 325. Piso was among the Arianism-inclined bishops at the Council of Sardica (344) who withdrew and set up their own council at Philippopolis; he later returned to orthodoxy and signed the profession of Nicene faith at a synod in Antioch in 363. Cyriacus was at the First Council of Constantinople in 381. Anatolius is mentioned in a letter of Saint John Chrysostom. Cyrillus was at the Council of Ephesus in 431 and at a synod in Tarsus in 434. Philippus took part in the Council of Chalcedon in 451 and was a signatory of the joint letter of the bishops of Cilicia Prima to Byzantine Emperor Leo I the Thracian in 458 protesting at the murder of Proterius of Alexandria. Ioannes participated in the Third Council of Constantinople in 680. No longer a residential bishopric, Adana is today listed by the Catholic Church as a titular see.

At the Battle of Sarus in April 625, Heraclius defeated the Sasanian Shahrbaraz forces that are stationed at the east bank of the river, after a fearless charge across the Justinian bridge (now Taşköprü). Byzantines defended the region from encroaching Islamic Caliphates throughout the 7th century CE, but it was finally conquered in 704 by the Umayyad Caliph Abd al-Malik. During Umayyad rule, Cilicia became a no man’s land frontier between Byzantine Christian and Arab Muslim forces. In 746, profiting by the unstable conditions in the Umayyad Caliphate, Byzantine Emperor Constantine V took control of Adana in 746. Abbasid Caliphate took over the rule of the region from Byzantine after Al-Mansur‘s inauguration to caliph in 756. With the Abbasid rule, Muslims for the first time started settling in Cilicia. Abandoned for more than 50 years, Adana was garrisoned and re-settled from 758 to 760. To form a Thughūr on the Byzantine frontier, Cilicia was colonized with the Turkic Sayābija tribe from Khorasan. The city had seen rapid economic and cultural growth during the reign of Harun al-Rashid and Al-Amin. Abbasid rule of the city continued for more than two centuries, and the Byzantines retook control of Adana in 965. The city became part of the Seleucia theme. After the defeat at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, the emperor Romanos IV Diogenes was removed from reign by a coup. He then gathered a troop to regain his power, though got defeated and had to retreat his troop to Adana. He was forced to surrender by the garrison in Adana upon receiving assurances of his personal safety.

Suleiman ibn Qutulmish, the founder of the Anatolian Seljuk Sultanate, annexed Adana in his campaign in 1084. Cilicia had been criss-crossed by invading armies and the crusades during this period until it was captured by the forces of the Armenian Principality of Cilicia in 1132, under its king, Levon I. It was taken by Byzantine forces in 1137, but the Armenians regained it around 1170. Armenian era had evolved Adana to a center for handicrafts and international trade. The city was the center of a large trading network from Minor Asia to North Africa, Near East and India. Venetian and Genoese merchants frequented the city to sell their goods that were brought through Ayas port. In 1268, the devastating Cilicia earthquake destroyed much of the city and 80 years later in 1348, Black Death reached the region and caused severe depopulation. Adana remained part of the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia until 1359, when the city was ceded to the Turkmen supported Mamluk Sultanate who marched into Cilicia and captured the plain. Most Armenians of the city fled to Cyprus after the ceding.

Turkic era

The Mamluks built garrisons in Tarsus, Ayas port and Sarvandikar, and left the administration of Adana plain to Yüreğir Turks who already formed a Mamluk authorized Turkmen Emirate in Camili area in 1352, just southeast of Adana. The Amir, Ramazan Bey, designated Adana as the capital, and headed the Yüreğir Turks in settling the city. The emirate which later on known as the Ramadanid Emirate, were de facto independent throughout the 15th century, by being a Thughūr in the Ottoman-Mamluk relations. In 1517, Selim I incorporated the beylik into the Ottoman Empire after his conquest of the Mamluk state. The Ramadanid Beys held the administration of the new Ottoman sancak of Adana in a hereditary manner until 1608.

The Ottomans terminated the Ramadanid administration in 1608 after the Celali rebellions and commenced ruling directly from Constantinople through an appointed Vali. In late 1832, Vali of Egypt, Muhammad Ali Pasha, invaded Syria, and reached Cilicia. The Convention of Kütahya that was signed on 14 May 1833, ceded Cilicia to the de facto independent Egypt. At the time of ceding, the Adana sancak population of 68,934 hardly received any urban services. First neighborhood (Verâ-yı Cisr) east of the river was founded and Alawites brought here from Syria to work at the flourishing agricultural lands. İbrahim Paşa, the son of Muhammad Ali Paşa, demolished the Adana Castle and the city walls in 1836. He built the first canals for irrigation and transportation and also built a water system for the residential areas of the town, including wheels raising the water of the river for public fountains. After the Oriental crisis, the Convention of Alexandria that was signed on 27 November 1840, required the return of Cilicia to Ottoman sovereignty. The American Civil War that broke down in 1861, faltered the cotton flow to Europe and directed European cotton traders to fertile Cilicia. Adana had evolved to be a hub for cotton trade and one of the most prosperous cities of the Ottoman Empire within decades. New Armenian, Turkish, Greek, Chaldean, Jewish and Alawite neighborhoods were founded, surrounding the formerly walled city. Adana–Mersin railway line was opened in 1886, connecting Adana to international ports through Port of Mersin.

City of Adana

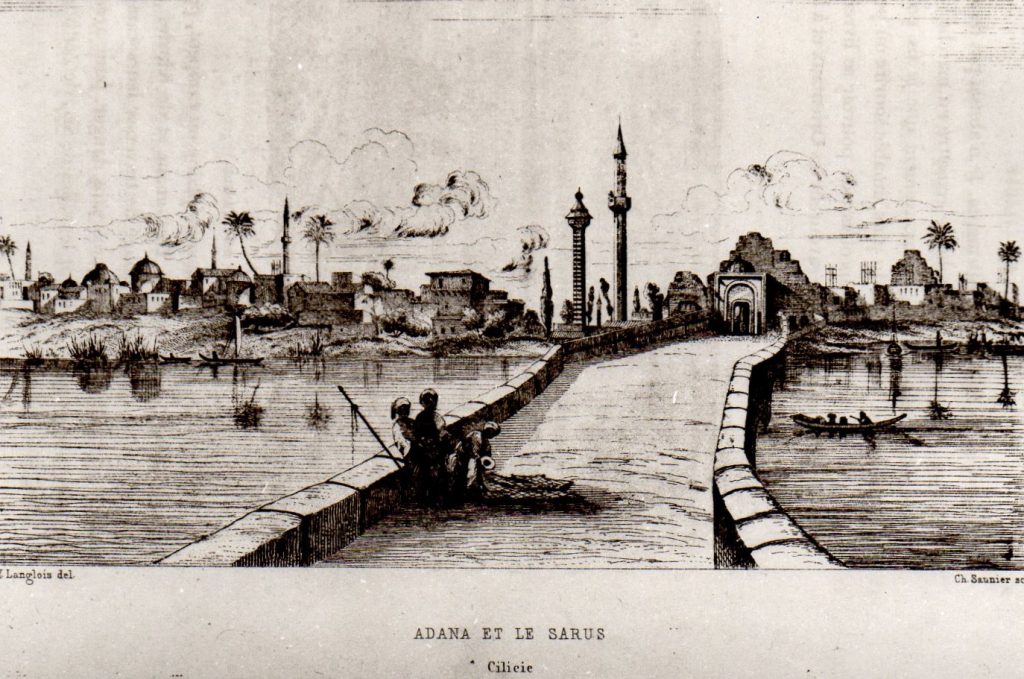

Adana is located in the lower reaches of the Seyhan (Saros, Sarus) River, where the river becomes navigable. “Adana is a commercial city, built on the right bank of the Sihoun river, the Sarus of antiquity. Its situation is in plain; it is dominated by a Byzantine castle which commanded the course of the river, in the west of the city. At the time of Pompey, it was inhabited by a colony of pirates that he established there. Its bridge over the Sihoun was built by the Emperor Justinian. Adana exports timber, cereals and wines.”[1]

Armenian Population

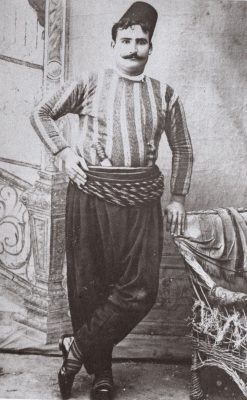

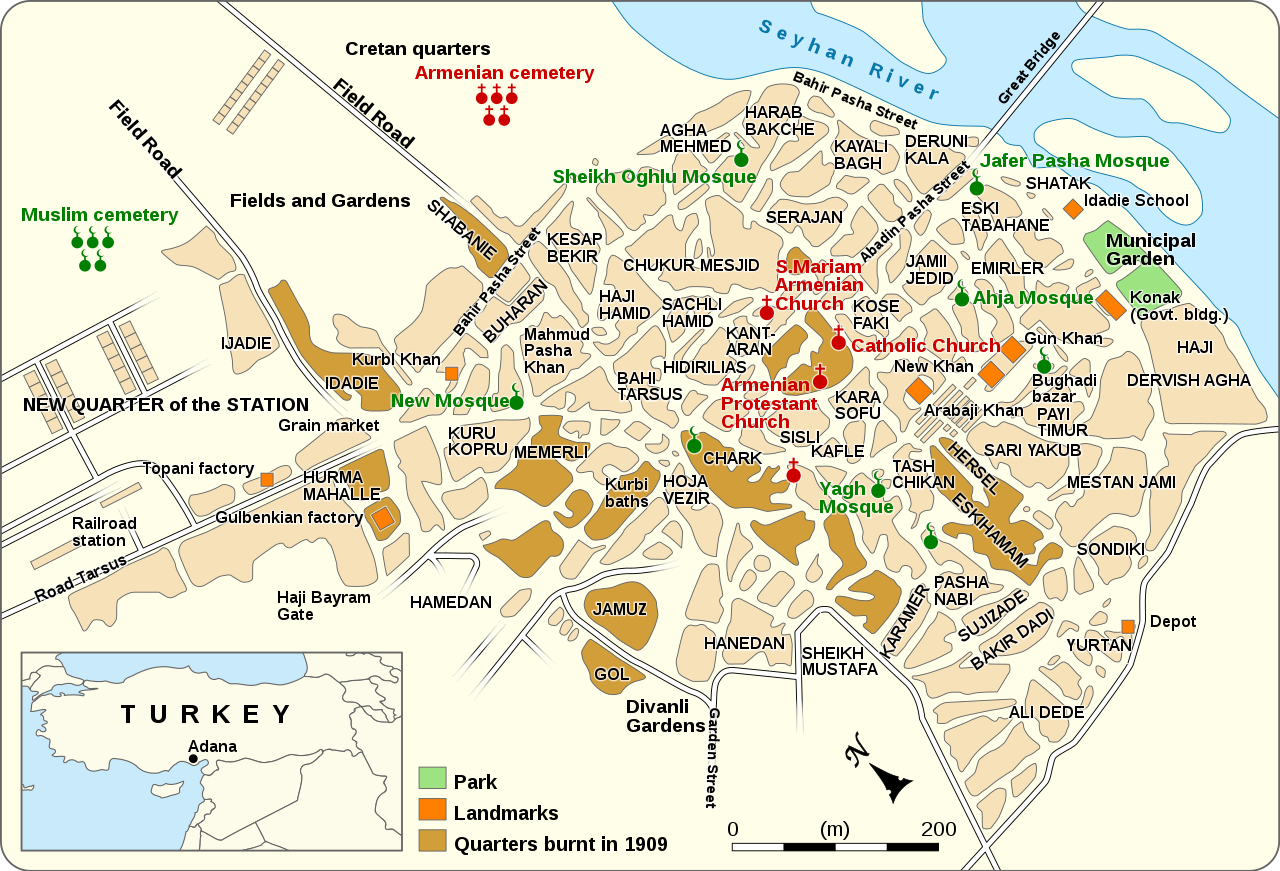

At the beginning of the 19th century Adana had about 12,600 (3,000 houses) Armenian inhabitants, whose well-maintained houses (mostly two-storied) were surrounded by orchards and flower gardens. Further migration that had attracted by the large-scale industrialization, inflated the population of Adana to over 107,000 at the turn of the 20th century: of these, 62,250 were Muslims (Turks, Alawites, Circassians, Kurds), 30,000 Armenians, 8,000 Chaldeans, 5,000 Greeks, 1250 Assyrians, 500 Arab Christians and 200 “internationals”.[2]

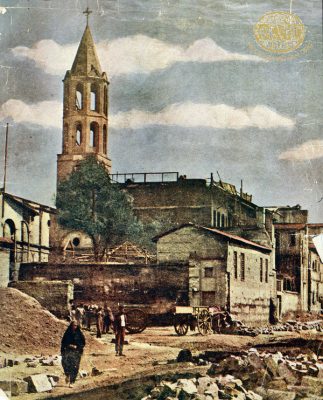

Armenians lived in the central parts and in the southwestern part of Adana, engaging in handicrafts, agriculture, and commerce. Before the 1909 Adana massacres, when 10,000 Armenians were massacred, there were 6 Armenian churches, 16 schools and colleges in the city.

The Apostolic Armenians had one kindergarten, three gymnasiums under the supervision of the Armenian Apostolic Church (Abgaryan, Ashkhenyan, Aramyan, etc.) and two colleges with a total enrolment of 1,500 students. The Catholic Armenians (170 houses) had one church (Immaculate Conception) and a school named after the Virgin. There was a Latin (Catholic) school where most of the students were Armenians. The small number of Armenian Protestants had their own schools in Adana. Catholic and Protestant Armenians had one church each, the Apostolic Armenians the four churches of Surb Minas, Surb (H)Amberd (or Anmarat Hghutyan, The Holy Mother of God/Surb Astvatsatsin and Surb Stepanos.

During the rule of Sultan Abdülhamit II, as during the rule of Republican Turkey, everything was done in Cilicia, particularly in Adana, to change the ethnic composition of the population. For this purpose, Balkan Turks were brought from different parts of the Ottoman Empire, as well as the Islamized Greeks of Crete. The Ottoman government settled in Adana the Chechens, Circassians, Dagestanis and Abkhazians, who lived mainly near the Armenian quarters. As a result, the local Armenians began to be persecuted by Muslim subjects, were often displaced and driven out of Cilicia.

During 300 years of Ottoman rule, the Armenians of Adana were linguistically Turkified, but as a result of the Armenian Enlightenment, followed by the opening of numerous Armenian schools, the Armenian language began to revive. In addition to Turkish, the local youth spoke French and English fluently.

The industry and trade of the city were concentrated in the hands of the Armenians. They possessed numerous factories (mahogany, silk, cotton, paints, vodka, beer, etc.), workshops (jewelry, silversmithing, carpet weaving, leatherwork, pottery, etc.), mills. Many hotels and banks belonged to local Armenians.

Four Armenian newspapers were published in Adana (“Adana”, “Kilikia”, “Hay Dzayn”, “Tavros”).

History

Adana is mentioned from the 5th century B.C. and thus one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world and with a name unchanged for at least four millennia, Adana was a market town at the Cilicia plain and one of the gateways from Europe to the Middle East. The city turned into a powerhouse of Cilicia with the Turkic takeover in 1359. It remained as the capital of the Ramadanid Emirate until 1608, and then the regional center for the Ottoman Empire, Turkey and shortly for French Cilicia. The city boomed with the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861 and emerged as a hub for the international cotton trade. Traditionally a town populated by Armenians and Turks; the influx of Syriacs, Greeks, Circassians, Jews and Alawites during this period made the city one of the most diverse cities of the Empire.

In the 3rd and 2nd centuries B.C. it was a center of Hellenistic culture. Under Roman rule (1st-4th century A.D.) it was turned into a military base, cultural life declined significantly. It was somewhat rebuilt and renovated during the reign of Byzantine Emperor Justinian I (527-565). The stone bridge built on the Saros River in the 6th century (22 arches, the flight is about 200 m) is still standing

In the 11th century, when the Crusaders passed through Cilicia, the Armenian population prevailed in Adana. The city was under the rule of the treasurer Prince Oshin, the lord of the Hetumian House, residing in Lambron. In the fall of 1097, the Crusaders captured Adana. After liberating the Plain of Cilicia in 1130-1132, Prince Levon I annexed Adana to the newly formed Rubinian government. In the 12th – 14th centuries Adana was part of the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia and famous as a center of handicrafts and commerce. In the 13th -14th centuries the royal palace was built in Adana, together with the churches auf Surb Minas, the Holy Mother of God/Surb Astvatsatsin and Surb Stepanos. In the western part of the city, a fortress was built on a rock rising along the riverbank, surrounded by towered walls (destroyed by the Ottomans in 1836).

At the beginning of the 14th century, Adana is remembered as a “magnificent royal city”, where the “world conference” of secular dignitaries convened in 1316 to discuss the unification of the Armenian and Catholic churches (see below section “Adana Assembly”). After the fall of the Armenian statehood in Cilicia (1375), Adana was captured and destroyed by the troops of the Arab sultanate of Egypt. From 1378 the city was occupied by the Turkmen of the Ramazan dynasty, from the second half of the 15th century by the Ottoman Turks. The Ottoman conquerors converted the magnificent church of Surb Hakob into a mosque and called it Ulucam.

But for a long time, it was impossible to eliminate the independence of the Armenians of Adana: in the 17th century, Armenian Khojas (Khachatur, Sargis, Manuk and others) are remembered as the main landowners of the city.

Adana Assembly (1316)

The meeting in Adana was held on 18 July 1316, in the city of Adana on the initiative of King Oshin I and Catholicos Constantine III of Caesarea. With the expectation of receiving military support from European powers against the attacks of the Muslim authorities, the congregation considered joining the Catholic Church (at the suggestion of Pope John XXII of Avignon). 18 bishops, 7 monks and 10 princes took part, but their wish for unification did neither represent the wish of Armenia itself (which was not represented at all in the assembly), nor did it correspond with the desire and opinion of the majority population of Cilician Armenia. The Assembly of Adana reaffirmed the new theological rules adopted by the Council of Sis in 1307, but not implemented, by which the Armenian Church was de facto joined to the Catholic Church.

A Center of Armenian Writing (13th -14th centuries)

The first writer mentioned is Stephen, who in 1244, by order of Smbat Sparapet, copied from Aristotle. In 1284, the scribe Constantine copied a collection kept now in the Matenadaran of Yerevan (manuscript N 4207), and in 1290 Khachatur copied the Gospel. Famous scribes of the late 13th century – Stepanos Goyneritsantsi, Petros and others – copied the Bible, which was edited under the archimandrites (vardapets) Gevorg and Khachatur. In 1610, Mesrop Mashtots was copied in of Adana. Memoirs are left of Abraham, a teacher of writing, from whom we have received a hymn copied in 1639. They also imitated Sharaknots (hymns) and the Armenian historian Movses Khorenatsi (1646) and Catholicos Sahak (1659). More than ten manuscripts are known from the 17th and 18th centuries, some of which are preserved in the Matenadaran in Yerevan.

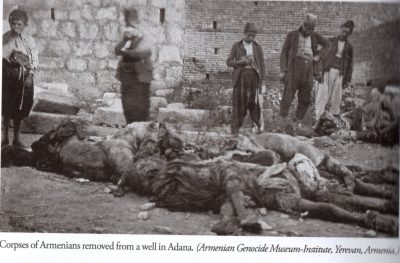

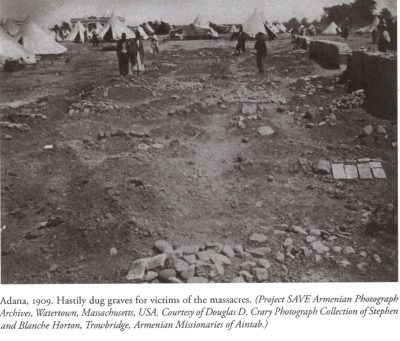

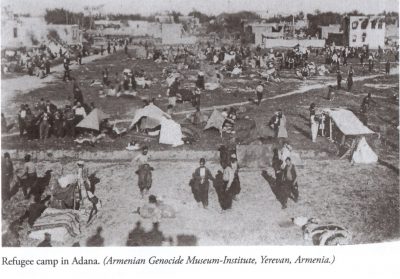

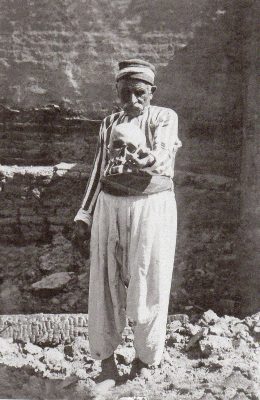

Destruction

10,000 Armenians in Adana fell victim to the massacres organized by the Young Turkish government in 1909. A significant number of Adana Armenians were annihilated in 1915, during the Great Genocide. In 1919, when the Armenian-French troops liberated Cilicia, many of the surviving Armenians returned to their hometown and began rebuilding the economy. In 1910-1922, the three-day Turkish-language newspaper ‘Adana’ in Armenian was published in Adana, together with the Armenian newspapers ‘Cilician courier’ and ‘Nor Serund’ (New generation). After the French surrender of Cilicia to Kemalist Turkey and the withdrawal of Anglo-French troops, the Armenians of Adana left the city in 1922-1923.

According to Protestant organizations in Turkey, many of Adana’s Protestants are of Armenian origin. Two old Armenian churches have been turned into mosques. A third Armenian church houses the Central Bank of Adana. Another Armenian church serves members of the city’s Catholic community. “Parts of the city have preserved the old Armenian buildings, and time here seems to stand still waiting for justice.”[3]

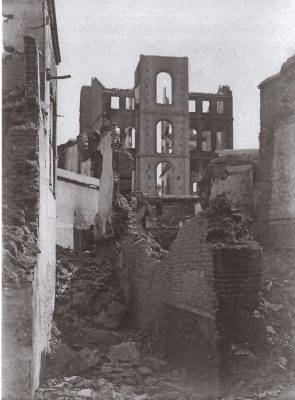

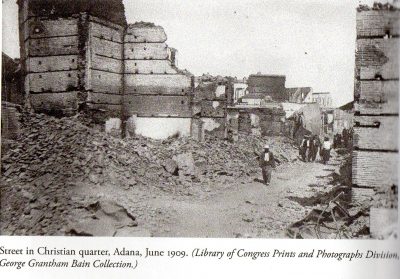

Adana Massacres (1909)

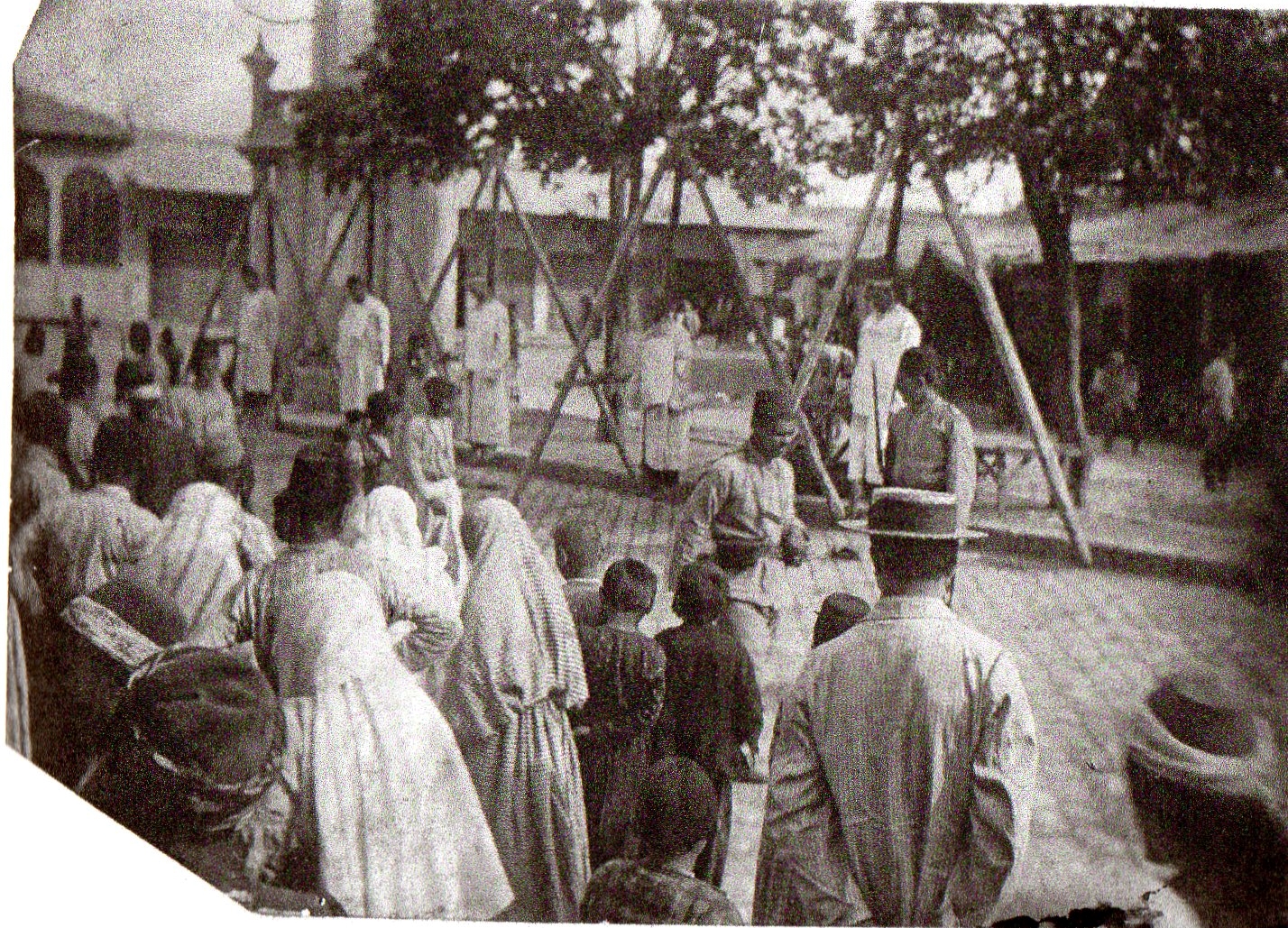

The massacres in the Adana and Aleppo provinces took place in April 1909, at the instigation of the Young Turkish government. Since 1908, dissatisfied Muslim reactionary forces had begun to accuse the Armenians of bringing “Hürriyet” by overthrowing the constitutional order, and allegedly seeking to seize power from the Ottomans and restoring the Armenian kingdom. On 31 March 1909, the Adana Provincial Council, chaired by the Governor, decided to exterminate the Armenians. Secret instructions were sent to start the massacre. On the eve of the massacre, the local government armed the Muslims and released about 500 criminals from prisons. The Muslim fanatical mob massacred thousands of Armenians on 1-4 April. On 12-14 April, the third and most barbaric and bloody massacre was attended by the regular Young Turkish-Ottoman military units sent from Rumelia to ‘restore’ order.

The Armenians of Dörtyol, Hadjin, Sis, Zeytun, Sheikh-Murat, and several other settlements were saved by their heroic self-defense. In an effort to avoid responsibility, to mislead public opinion, and to soften the grievances of the Armenians, the Young Turks launched a lengthy trial, but the real leaders and perpetrators of the Adana massacre went unpunished.

After the Adana massacres the Armenian residents tried to restore their districts in the city, but the continuous genocide did not allow it. Hundreds of homeless Armenians were looking for a place to live in nearby cities.

1915-1922

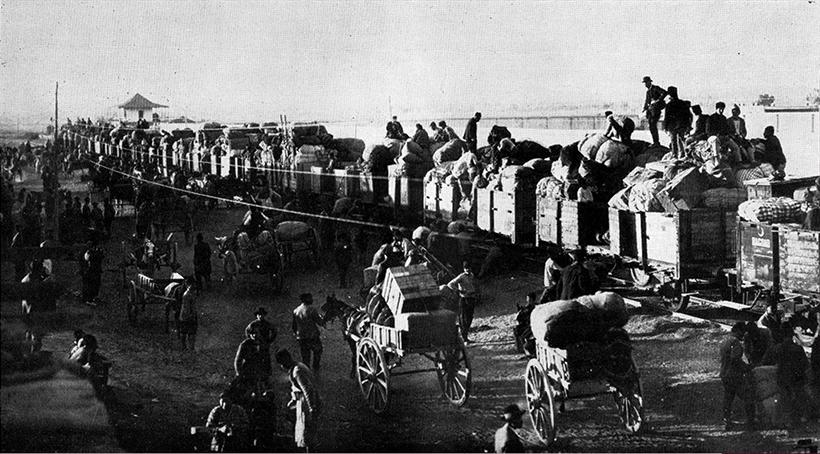

On 20 May 1915 the first convoy of deportees from Adana, comprising thousands of Armenians, was sent to Syria. From mid-August to 1 September 1915 further 5,000 families (20,000 individuals) were deported in

eight convoys to Syria under the supervision of Ali Münif, Deputy of Adana and assistant to the Minister of the Interior, Talat, and the Director of police, Adıl Bey.[4]

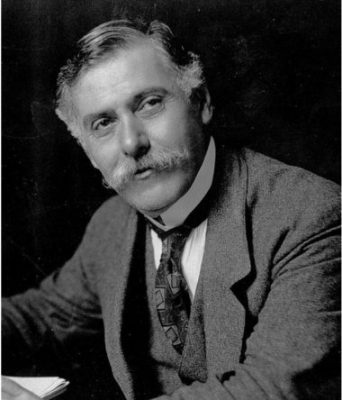

There were no Armenians left in the city of Adana after the genocide of 1915/16, but after the First World War, when Cilicia passed into the hands of France, some Armenians returned or settled there. On 4 August 1920, in Adana, led by Mihran Tamatian (Western Armenian: Damatian; Constantinople, 1863/4- Cairo, 1945), the Armenian independence of Cilicia was proclaimed, which was only of a figurative nature. Soon the French military authorities handed over Adana and all of Cilicia to Kemalist Turkey. Most of the Armenians of Adana emigrated to Syria and Lebanon. (See also sections “Destruction” and “Cilicia under the French Mandate (1919-1921) and its Reconquest by the Kemalists“ on the site “Province of Adana”).