Toponym

Karin/Erzurum is one of the most ancient settlements of the Armenian Highlands. Its foundation is attributed to a king Karanni, who lived in the second half of the 2nd millennium B.C., from which the toponym ‘Karin’ originates.

Armenian Population

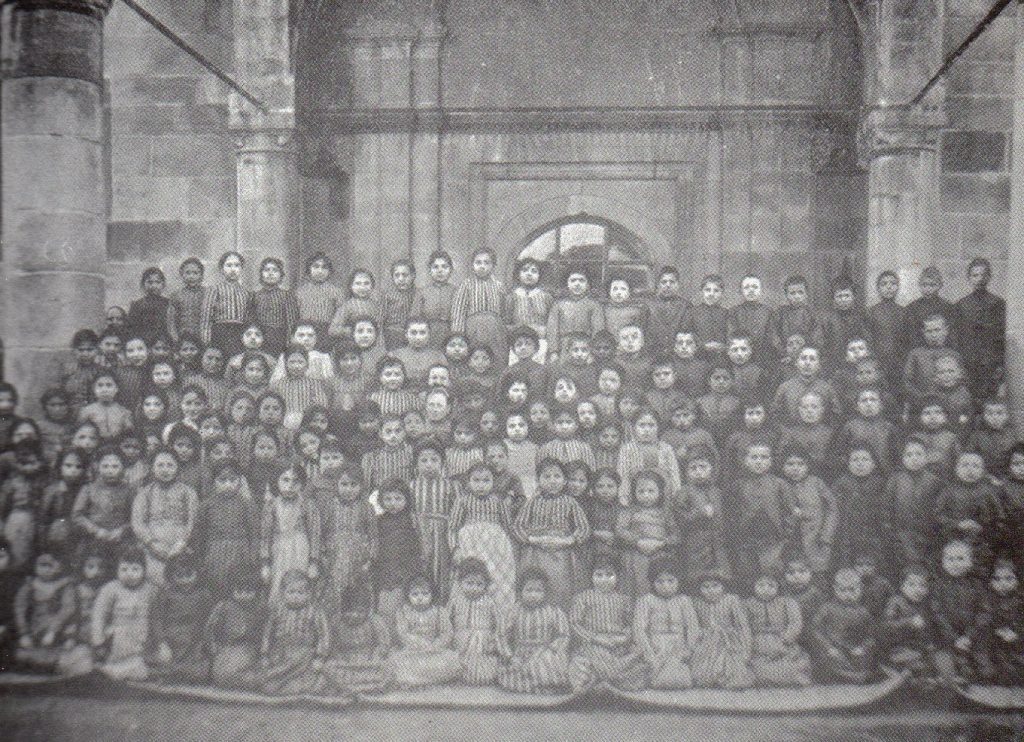

Before the First World War, 37,480 Armenians lived in 53 localities of the kaza of Erzurum, maintaining 43 churches, three monasteries and 52 schools with an enrolment of 6,355 children.[1]

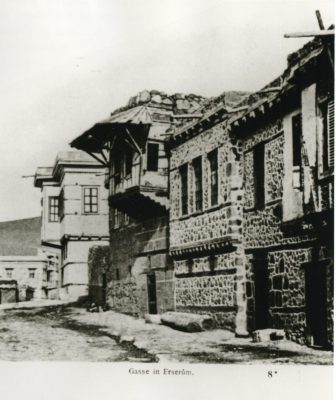

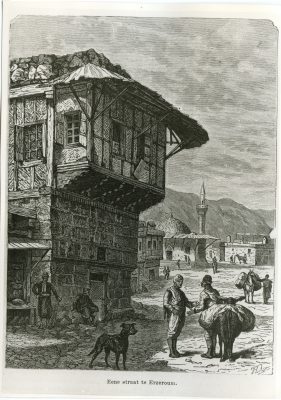

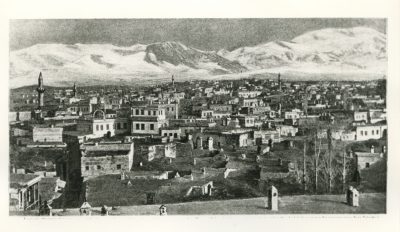

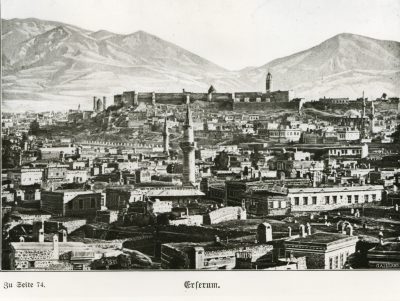

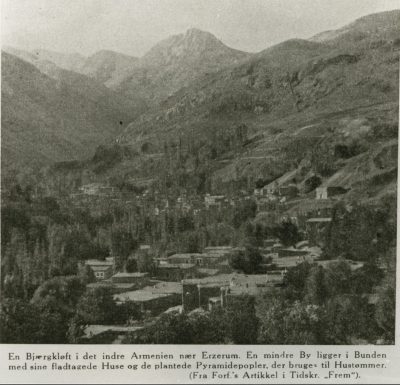

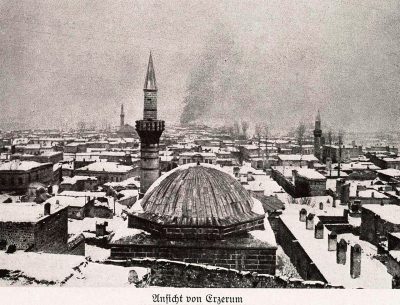

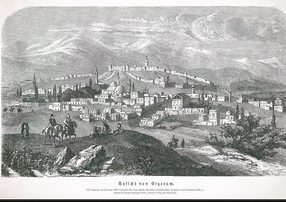

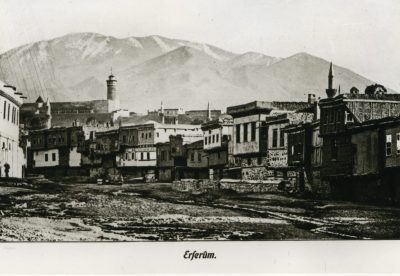

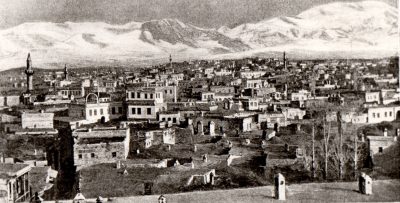

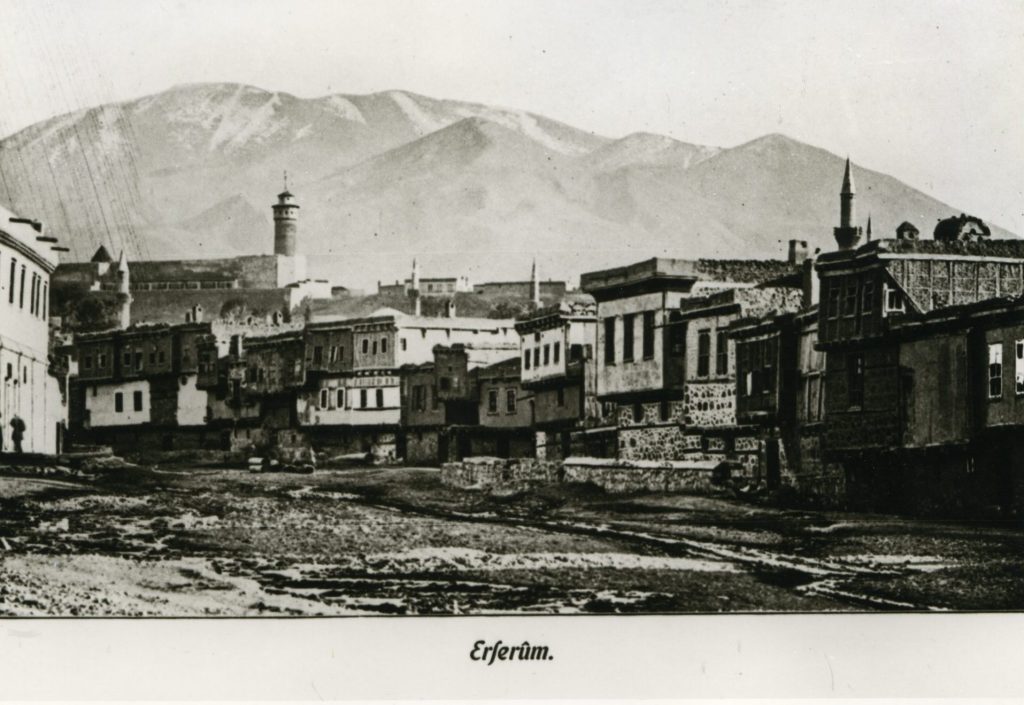

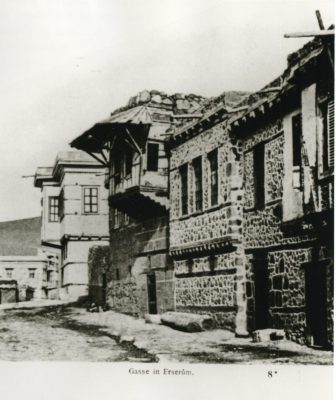

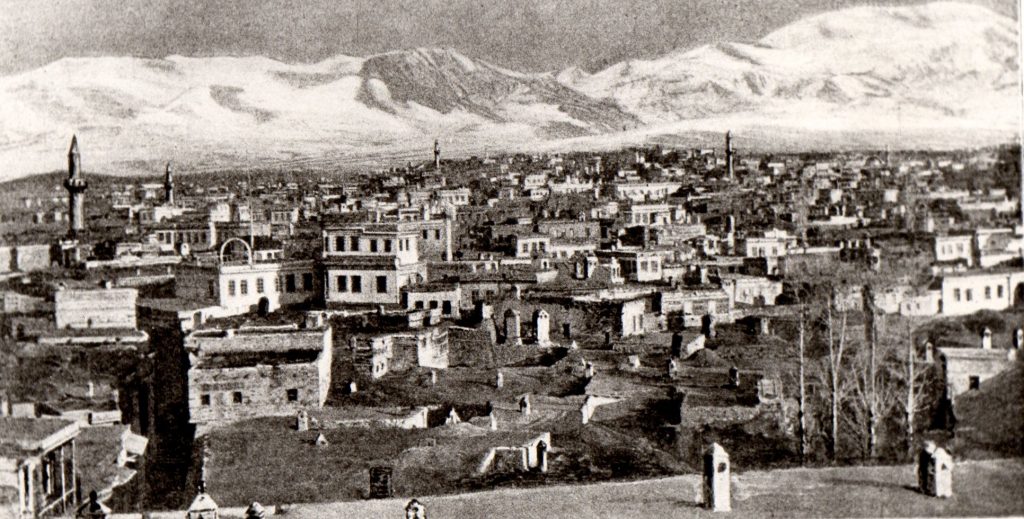

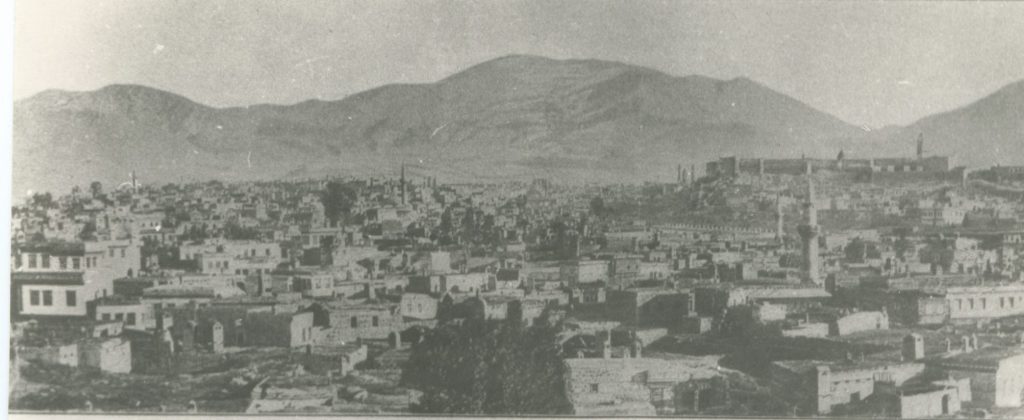

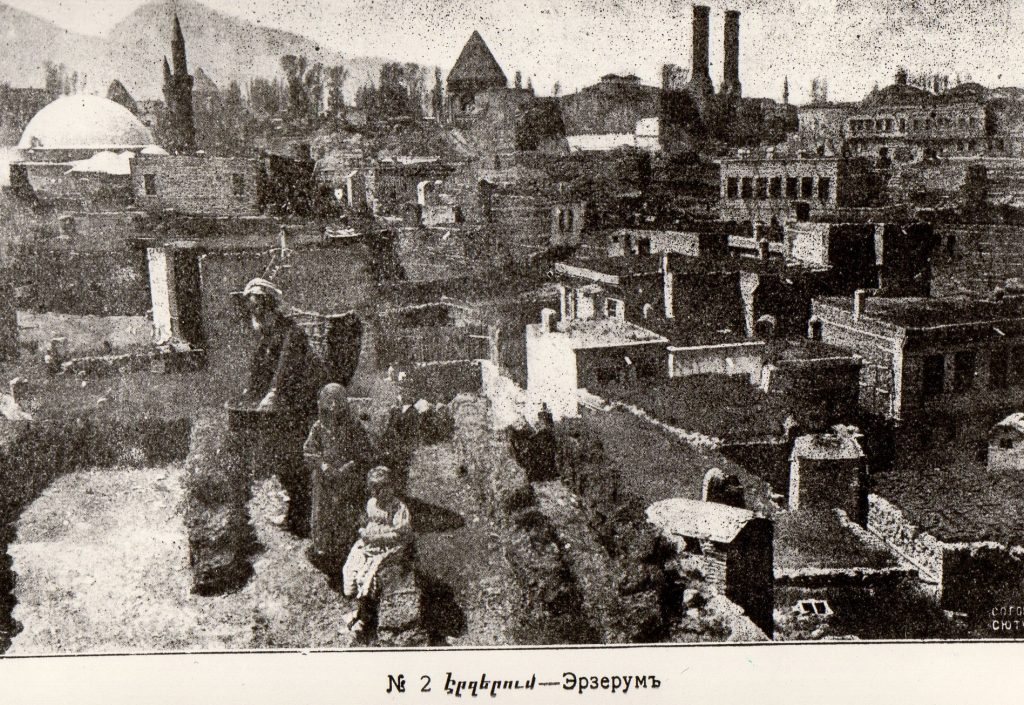

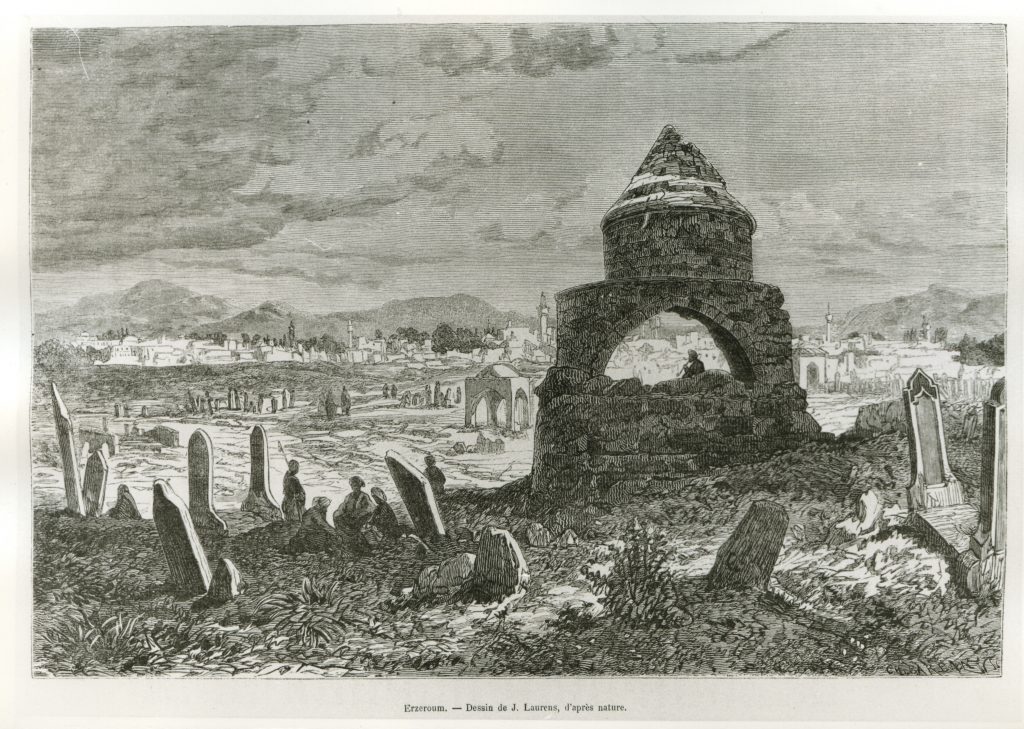

City of Erzurum – Կարնոյ քաղաք

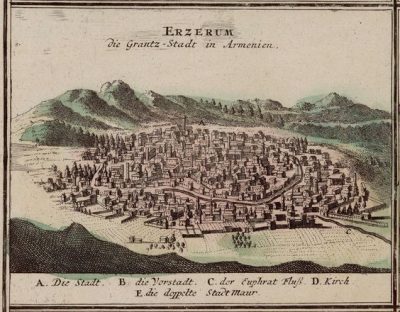

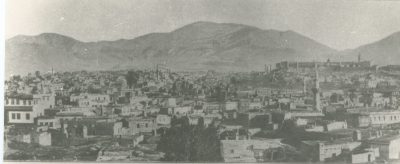

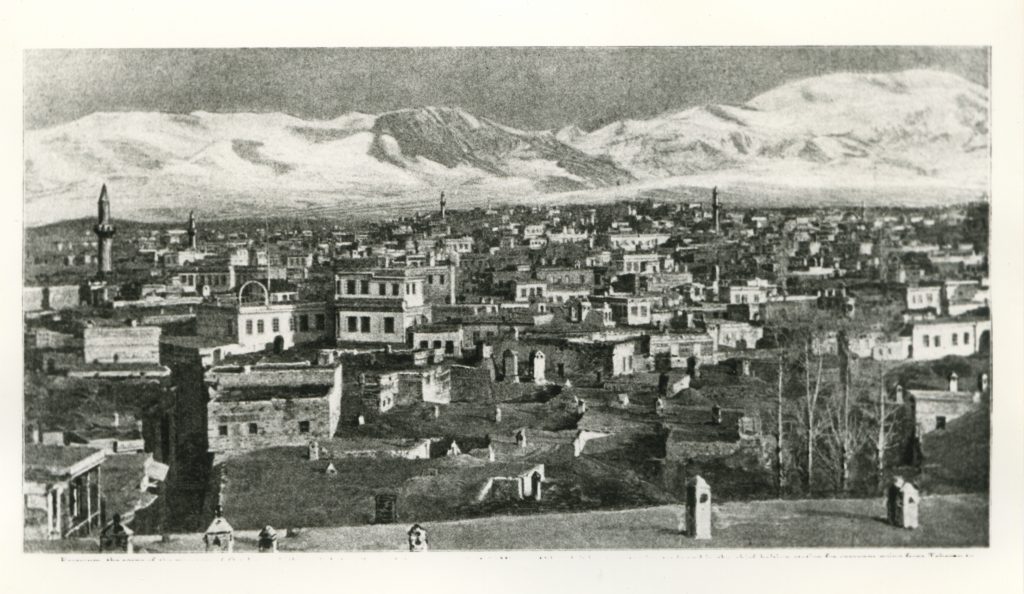

Erzurum is situated on the left bank of the Euphrates River, at an altitude of about 2000 m above sea level. To the south of the city are the hills of Mount Havatamk. The Davaboyn mountain range stretches in the east, and the Karin plain spreads near the city to the north and west. Due to the harsh climate, only potatoes, cabbage, carrots, and a few greens were grown in the surrounding vegetable gardens.

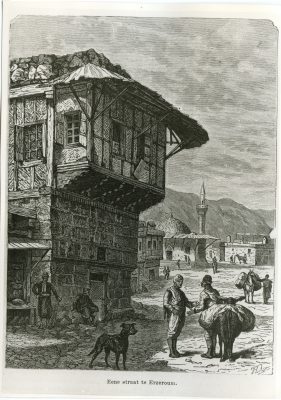

“Through Erzurum runs a road of great strategic and commercial importance. This was the historic trade route from Trebizond to Tabris. As a result, Erzurum was a busy center for commerce, and the Armenians, together with the Greek and Persian merchants, took an active part in its trade. A. Do [A-To, i. e. Hovhannes Ter Martirosian] gives his eye-witness account of the share which Armenians had in this trade and handicrafts of the province. Speaking especially of the city of Erzurum, he says:

‘The Armenians deal mainly with commerce and handicrafts. The crafts are well developed here. In Erzurum there are more than 3,000 shops and taverns, of which nearly half belong to Armenians. About 500 of these Armenians are retail dealers, some are big merchants who have commercial relations with Istanbul and other towns. More than 1,000 people are occupied in crafts of which the most advanced – masonry – supports many Armenian families not only on the towns, but also in the villages on the plain.’”[2]

Economy

Located at the junction of major commercial highways, Karin/Erzurum has always been of great economic importance. It maintained close trade links with Constantinople, Trebizond, Tabriz, Yerevan, and Tiflis. The Trebizond-Bayburt-Erzurum highway, built in 1856-71, about 300 km long, further activated the connection with the outside world. After that, the construction of the Erzurum-Hasankale road was completed. In 1915 Erzurum had a railway connection with Sarıkamış. Silk, fine cotton fabrics, spices, glassware, medicine, vegetable oil, coffee, toiletries, and other goods were brought to the city by these roads.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the city had several markets, 12 squares, 32 caravanserais and downhill, 18 baths, 150 taverns, 180 bakeries. In Erzurum in the 1870s, there were four home-made enterprises of ham (basturma) and meat (sujuk, sucuk), which belonged to Armenians. In the middle of the 19th century, there were 6 leather, several oil distillery, painting and other enterprises in Erzurum. Table salt was mined near the city. In the 1880s, the Italian count Conte de Birzani founded a tobacco factory in Erzurum, some of whose raw materials were brought from Trebizond. On the eve of World War I, German entrepreneurs were given the right to explore for oil in the vicinity of Erzurum.[3]

Armenian Population

The long rule of foreigners has significantly changed the ethnic

composition of the population of Karin to the detriment of the Armenians. 1829 Karin had about 130,000 inhabitants, of which 30,000 were Armenians, in 1909 60,000 inhabitants, of which 15,000 were Armenians (2,500 families). The Constantinople based German diplomat and scholar of Oriental studies, Johannes Heinrich Mordtmann estimated in mid-May 1915 that Erzurum had “2,000 Armenian houses”.[4] Armenians mainly lived in the northern and northwestern districts of the city, where the consulates of the USA, England, France and Russia were also situated.[5]

Armenian craftsmen of Erzurum were famous in jewelry, tailoring, blacksmithing, armament, masonry, leather, fur-making, and copper-making. The colorful and elegant carpets and other handicrafts made by Erzurum’s women were very popular in the markets of Armenia and abroad.

Karin/Erzurum was a major center of Armenian culture and enlightenment. Its oldest educational institution was the Central Mother School, which was founded by Archbishop Karapet Bagratuni in 1811. Later it was renamed Three-Year Co-Educational School of Ardzn (Ardznyan). In 1909 it had 334 students and 9 teachers. At the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, the schools of Aghabalyan, Ardznyan (second), Galfayan, Hripsime, Msryan, and Ter-Azaryan operated in Erzurum. The Sanasaryan nine-year school for boys (1881-1916) had a special place in education. Together with students in private schools, in 1909 the number of Armenian pupils in Erzurum exceeded 2,800.

In 1878 a theatrical union was founded in Erzurum. At that time there were 3 kindergartens in the city. Before the First World War, the Armenian periodicals Haraj, Sirt, Alikt, Yerkir, and Luys were published in Erzurum. After the Congress of Berlin (1878), the policy of persecution started by sultan Abdülhamit II challenged the Armenians of Erzurum to fight for their rights. In 1881, the Defender of the Fatherland group was founded there, which pursued the goal of national liberation.

Notable Armenians

- Karekin (Garegin) Pastermadjian (Գարեգին Փաստրմաճեան; Armen Garo; 1872–1923): Ottoman MP, Armenian Ambassador and leader of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (Dashnaktsutyun)

- Hakob Karnetsi (Jacob of Karin; 1618-after 1672); cleric, historian

- Hovhannes Karnetsi (c. 1750-1820): poet, educator and notary by profession

- Yeghia Karnetsi: Head of the “Defender of the Fatherland” (Pashtpan hayrenyac) group

- Mekhak Guyumjian (Kouyoumjian; 1876-1913): writer

- Shavarsh Garagash (1893-1952): writer

- Aram Yerkanian (Yerganian – Արամ Երկանեան; 1900-1934): Revolutionary and avenger

- A. Alexanyan (1910-1942): Soviet Armenian painter

History

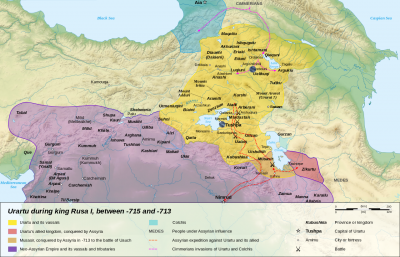

In the Iron Age, the kingdom of Diauehi (Dayaeni, Daiaeni), which is known from some Assyrian inscriptions, was probably located in the vicinity of Erzurum. Later, the area was part of the Urartu Empire. After the decline of Urartu, the Iranian Achaemenids ruled there. Erzurum was then part of various empires and dynasties. These include the Artaxids, Macedonians, Parthians, Sassanids, Armenians, Romans, Byzantines, Arabs and various Turkish principalities such as the Saltukids. Erzurum was several times the border of two rival empires, such as Rome and Parthia or Ottoman Empire and Russia.

The capital Erzurum was the seat of a titular bishopric and the seat of a bishop. With the Arab conquest, the area was gradually Islamized, but there were still many Christian Armenian communities. Until the Armenian Genocide, the Monastery of Saint Minas of Kes was operated in the village of Gezköy.

Historically reliable information about Karin has been preserved in the works of Greco-Roman (1st century) and later Armenian historians.

Karin’s role and significance began to grow especially after the first division of Armenia in 387, as the strongest border fortress city of the Byzantine Empire. By order of the Roman Emperor Theodosios II (408-450), General Anatoly built new fortifications in Karin in 431 and renamed the city Theodosioupolis. The fortifications and defensive structures of the city were expanded and rebuilt during the reign of Anastasios I (491-518) and especially during the reign of Justinian I (527-565). In the 7th-9th centuries Karin changes hands between the Byzantines and Arabs. After the establishment of the Bagratuni kingdom in Armenia in 885, Karin became part of the Armenian territorial state. In 949, however, the Byzantines seized it again. In 1049, when the Persians completely destroyed the city of Ardzn (Արծն), its surviving inhabitants settled in Karin. The Zakaryans expelled the Seljuks for a period, but in 1242 the city came under the rule of the Mongols. In the 15th century, Karin was successively ruled by the Ak and Kara Koyunlu tribes, and in 1514 it was conquered by the Ottoman Sultan Selim I.[6]

In the 19th and 20th centuries, Russian troops liberated the city from the Ottomans three times, but returned it three times. According to the Treaty of Adrianople (1829), when Russia for the first time returned Erzurum to the Ottomans, more than 20,000 Armenians left the city with Russian troops and settled in the regions of Akhaltsikhe, Akhalkalaki, Lori and Pambak. The emigrants renamed some of their new settlements after the villages of Karin province.

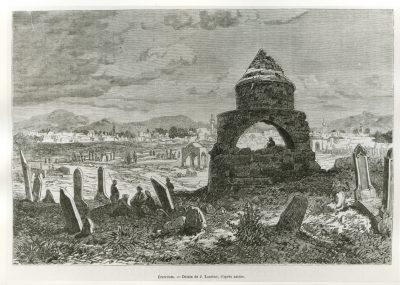

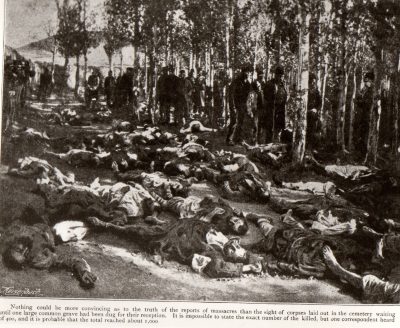

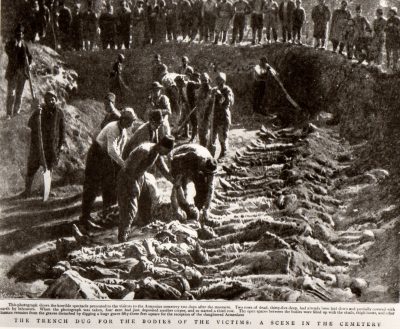

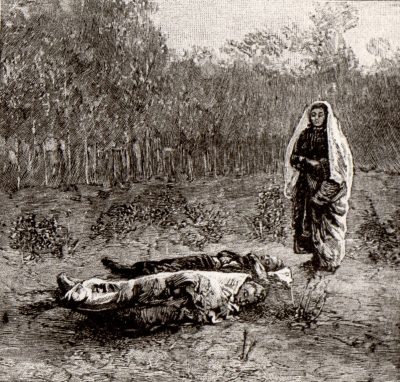

The Armenians of Erzurum lived in relatively secure conditions until the 1880s. In the 1890s the waves of massacres that started in Western Armenia, in the Armenian-populated regions of the Ottoman Empire, reached Erzurum. The massacre there began on 18/30 October 1895, when the Armenian priest of Tevnik and other Armenians were shot by soldiers in the office building of the provincial governor (vali), whom the people killed wanted to speak to there. Within a few days, Armenian homes and workshops were destroyed, set on fire and looted. The number of Armenians brutally killed was more than 1000 people. Hundreds of women and children were captured or abducted.[7]

In December 1914, in the city of Erzurum “many Armenians and Greeks suspected of espionage have been hanged, and their corpses suspended to lamp posts. Turks passing by spat on their bodies and compelled the Christians to do likewise.”[8]

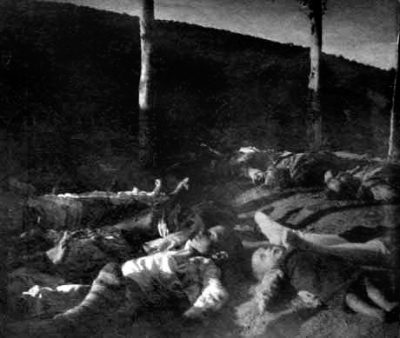

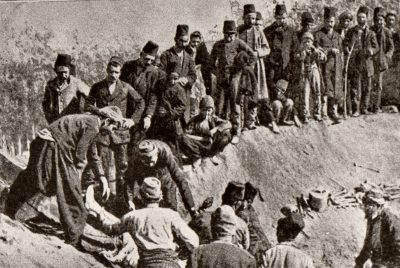

The complete destruction during the First World War started in mid-June 1915. On 16 June 1915 the first convoy of deportees, made up of the most influential Armenian families of the city, departed from Erzurum under the orders of the gendarmerie captain, Nusret, towards the south-west in the direction of Kıği and Palu.[9] The second convoy of deportees from Erzurum set off three days later, on 19 and 20 June in the direction of Bayburt. This convoy was made up of 1,300 middle-class families[10], who were joined en route by 370 families of the town of Garmirk (kaza of Kiskim), for a total of approximately 10,000 people. They were escorted by gendarmes commanded by captains Muçtağ and Nuri and supervised by two leaders of the Special Organization, the kaymakam of Kemah and Kozukçioğlu Münir.[11] On 20 June the men from the first convoy from Erzurum were assassinated, and many of the women kidnapped near the village of Çoğ by Kurdish irregulars directed by two Special Organization leaders, Ziya Beg of Başköy, and Adıl Bey (his real name being Adıl Güzelzade Şerif).[12]

In the end of June 1915, the second caravan from Erzurum, reached the killing field in the gorges of Kemah, at the middle of the bridge that spans the Euphrates. Squadrons of bandits commanded by Oturakçı Şevket and Hurukçizade Vehib screened the deportees. 800 to 900 men were separated from the convoy and killed by the Special Organization thugs commanded by Çetebaşı Cafer Mustafa on 18 July.[13] The survivors in the second caravan from Erzurum reached the plain of Fırıncılar, to the south of Malatya in July 1915; it was one of the main killing fields employed by the Teşkilat-ı Mahsusa, which was supervised by the deputy from Dersim, Haci Baloszade Mehmed Nuri, and his brother, Ali Pasha, who are under order from two Kurdish chiefs from the Reşvan tribe, Zeynal Bey and Haci Bedri Agha, along with Bitlisi Emin, a retired Gendarmerie Commander. 3,600 deportees were executed there at the knife, 2,115 of which were men.[14]

On 29 June 1915 the third caravan of deportees from Erzurum was put en route to Bayburt and Erzincan. It was made up of between 7,000 and 8,000 people, including 500 families from the Khotorjur district. At İçkale, a walking distance of ten hours from the town, 300 men were shot. A bit further, the surviving men suffered the same fate in the gorges of Kemah. It was in the gorges of Kahta, however, that the majority of the people in that convoy had their throats slit a few weeks later. Seven dozen escapees reached Mosul, in Mesopotamia.[15]

On 11 July 1915 7,000 deportees from Erzurum were executed and thrown into the huge Byzantine cisterns at Dara (sancak of Mardin) by men from the Sixth Army Corps commanded by general Ali İhsan Pasha.[16]

On 18 July 1915, the fourth convoy left Erzurum, comprised of 7,000 to 8,000 deportees, most of whom were workers in military factories, the families of soldiers, military physicians, pharmacists, and the primate of the Diocese, Mgr Smpat (Smbat) Saadetian; they were set en route to Bayburt. The Special Organization networks then took charge: men went to Kemah and women and children to Harput. Around 300 escapees, two of whom were men disguised as women, reached Cizre, and then Mosul.[17]

On 10 September 1915, 8,000 women and children from convoys originating in Harput and Erzurum were exterminated between Diyarbekir and Mardin, their killers being members of bandit squadrons of the Special Organization.[18]Another 2,000 women and children of convoys originating in Harput and Erzurum were exterminated on 14 September in the outskirts of Nisibin.[19] On 22 September 1915, two hundred soldier-workers from Erzurum were murdered some three hours from Cizre under the supervision of Halil Kut by Special Organization bands.[20]

In his memoir, Soghomon Tehlirian mentioned: “Of 18,000 Armenians of Erzeroum, only 120 remained, six of whom were men, the rest, women and children. All the Armenians in the villages of the region had been annihilated.” [21]

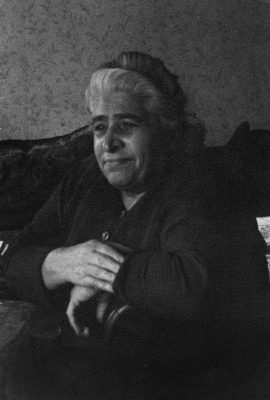

Genocide Survivor and Defense Witness Christine Terzibaschian

Christine Terzibashian was born around 1894 as Christine Eftian into a wealthy family in Erzurum. Her father Harutiun Eftian was a grocer there. Christine received a good education and, shortly before World War I, married Terzibashian, a mechanical engineer born in 1892, in late 1913. A year later, their first son Azat was born. He was only six months old when Christine and her family were deported from Erzurum in the summer of 1915. The genocide separated her from her husband, who was abroad. It was not until 7 April 1920 that she was able to travel to Berlin and was reunited with him. In the criminal trial of 2-3 June 1921, against Soghomon Tehlirian, who had shot the former Ottoman Interior Minister Mehmet Talat in Berlin on 15 March 1921, Christine Terzibashian testified as a defense witness. Christine Terzibashian referred to Talat as a ‘devil on earth’. She mentioned to her relatives the Kemakh Gorge on the Euphrates River, where she walked over dead bodies. After all, a grandson of Christine’s visited Erzurum. Her son Armen Terzibashian remembered his mother in a 2021 greeting as follows:

“My mother did not often and especially did not like to talk about her horrific experiences that she faced during the deportation from her homeland. But some conversations with her have remained in my memory, and I will report on

them in a moment. First, however, a few words about my mother herself. She was a motherly and strong personality and the most humble and loving person I was privileged to know in my life. The struggle for survival made her resourceful. This came to her aid in later life as a stateless person in a strange land. Her life was one of hardship and caution and her marriage was strongly influenced by oriental conventions. I do not recall that we ever took vacations, except for occasional excursions. At the same time, however, she was always helpful to others, and I feel fortunate to have been able to be with her. She died of her sick heart, which she had brought with her from the deportation, in Berlin in 1969.

In her conversations with me, her youngest son, her memories of the horrific experiences came flooding back. She told of endless marches, past countless corpses and dying people, of the paths without water and food, of the constant smell of decay, of her terrible thirst, which made her tongue as immobile as a stone.

She told me that one day her convoy came to a narrow place of the Euphrates River called Kemah Boğazı. There were so many bodies lying in the river there that they could have crossed it dry-footed.

The Turkish guards who accompanied the deportees were very brutal and shot the defenseless people at will. They were often assisted by released felons called çeteler. My mother had to watch helplessly the murder of her six-month-old son, who was smashed against a rock by one of the guards. She also had to endure and cope with the murder of her parents and many other members of her family. Of her large family, only she and two brothers survived. She endured and survived all that, how, she herself could not comprehend in large parts.

She was on the road for almost five years, at times she was accommodated by Kurdish nomads, which may have saved her life. On 7 April 1920, with the help of a Christian Armenian organization, she arrived in Berlin, where my father had been sent to study in May 1914. From then on she celebrated this day as her birthday.

The devil in human form, as she had often called Talat Pasha in her accounts, was not able to break her, even though he had declared Armenians fair game with his laws. When I think back, I admire her courage to live and her strength, which enabled her to master her unspeakably difficult life. Even when she was no longer there, she always gave me the strength to live.

Talat, who was sentenced to death as a war criminal, showed with his genocide, which was quickly forgotten by the world, how dictators can unscrupulously try to cleanse their country of foreigners; and other peoples stood by and watched. I fear that xenophobia has not yet been defeated. Here I think of the admonishing words of Bertolt Brecht: ‘The womb is fertile still from which this crawled!’“