The slightly elevated peninsula runs in a south-westerly direction into the Aegean Sea, between the Dardanelles (formerly known as the Hellespont), and the Gulf of Saros (formerly the bay of Melas). In antiquity, it was protected by the Long Wall, a defensive structure built across the narrowest part of the peninsula near the ancient city of Agora.

The peninsula was renowned for its wheat. It also benefited from its strategic importance on the main route between Europe and Asia, as well as from its control of the shipping route from Crimea. The city of Sestos was the main crossing-point on the Hellespont.

Administration

The sancak of Gelibolu or Gallipoli was a second-level Ottoman province (sancak or liva) encompassing the Gallipoli Peninsula and a portion of southern Thrace. Gelibolu was the first Ottoman province in Europe, and for over a century the main base of the Ottoman Navy.

From the second Ottoman conquest until 1533, Gallipoli was a sancak of the Rumelia Eyalet. In 1533, the new Eyalet of the Archipelago, which included most of the coasts and islands of the Aegean Sea, was created for Hayreddin Barbarossa, the Ottoman Navy’s Kapudan Pasha (قپودان پاشا, chief admiral), and Gallipoli became the seat and capital province (pasha-sancak, پاشا سنجاق) of the Archipelago, until the 18th century, when the Kapudan Pasha moved his seat to Constantinople

By 1846, the sancak of Gallipoli became part of the Eyalet of Adrianople, and after 1864, as part of the wide-ranging vilayet (ولایت) reform, of the Adrianople Vilayet.

Originally the sancak of Gallipoli included wide parts of southern Thrace, from Küçükçekmece on the outskirts of Istanbul to the mouths of the Strymon River, and initially even Galata and Izmit (Nicomedia).

With the vilayet reform of 1864, the sancak of Gallipoli comprised six kazas: Gelibolu, Şarköy, Ferecik (Feres), Keşan (Grk. Kesani), Malkara and Enoz. With the detachment of the new Sancak of Gümülcine in 1878, the sancak of Gelibolu was reduced in extent, and by World War I contained only three kazas: Keşan, Mürefte and Şarköy.

Toponym

Gallipoli is the Italian form of the Greek toponym Καλλίπολις (Kallípolis – ‘beautiful city’), the original name of the modern town of Gelibolu. In antiquity, the peninsula was known as the Thracian Chersonese (Ancient Greek: Θρακικὴ Χερσόνησος – Thrakiké Chersónesos – ‘Thracian Peninsula’; Latin: Chersonesus Thracica). Gelibolu is the Turkish verbalization of Greek Kallipolis.

Population

| Ottoman statistics of 1910 mentioned an overall population of 107,200 in the sancak of Gallipoli; of these, 31,500 were Turks, 70,500 Greeks, 2,000 Bulgarians and 3,200 “others”.[1] |

According to the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople, the Diocese of Gallipoli was composed by eleven communities with a total of 32,835 Greek Orthodox Christians.[2] Only 1,190 Armenians lived in the overwhelmingly Greek peninsula in 1914, working “principally in commerce and crafts”.[3]

From the early 17th century until the early 20th century, a relatively large number of Sephardic Jews lived in the town of Gallipoli, descendants of those fleeing the Spanish Inquisition.

History

According to Herodotus, the Thracian tribe of Dolonci (Δόλογκοι) (or ‘barbarians’ according to Cornelius Nepos) held possession of Chersonesus before the Greek colonization. Then, settlers from Ancient Greece, mainly of Ionian and Aeolian stock, founded about 12 cities on the peninsula in the 7th century B.C. The Athenian statesman Miltiades the Elder founded a major Athenian colony there around 560 BC. He took authority over the entire peninsula, augmenting its defenses against incursions from the mainland. It eventually passed to his nephew, the more famous Miltiades the Younger, about 524 B.C. The peninsula was abandoned to the Persians in 493 B.C. after the beginning of the Greco-Persian Wars (499–478 B.C).

The Persians were eventually expelled, after which the peninsula was for a time ruled by Athens, which enrolled it into the Delian League in 478 B.C. The Athenians established a number of cleruchies on the Thracian Chersonese and sent an additional 1,000 settlers around 448 BC. Sparta gained control after the decisive battle of Aegospotami in 404 B.C., but the peninsula subsequently reverted to the Athenians. During the 4th century BC, the Thracian Chersonese became the focus of a bitter territorial dispute between Athens and Macedon, whose king Philip II sought possession. It was eventually ceded to Philip in 338 B.C.

After the death of Philip’s son Alexander the Great in 323 B.C., the Thracian Chersonese became the object of contention among Alexander’s successors. Lysimachus established his capital Lysimachia here. In 278 B.C., Celtic tribes from Galatia in Asia Minor settled in the area. In 196 B.C., the Seleucid king Antiochus III seized the peninsula. This alarmed the Greeks and prompted them to seek the aid of the Romans, who conquered the Thracian Chersonese, which they gave to their ally Eumenes II of Pergamon in 188 B.C. At the extinction of the Attalid dynasty in 133 B.C. it passed again to the Romans, who from 129 B.C. administered it in the Roman province of Asia. It was subsequently made a state-owned territory (ager publicus) and during the reign of the emperor Augustus it was imperial property.

The Thracian Chersonese was part of the Eastern Roman Empire from its foundation in 330 A.D. In 443 A.D., Attila the Hun invaded the Gallipoli Peninsula during one of the last stages of his grand campaign that year. He captured both Kallipolis and Sestus. Aside from a brief period from 1204 to 1235, when it was controlled by the Republic of Venice, the Byzantine Empire ruled the territory until 1356. During the night between 1 and 2 March 1354, a strong earthquake destroyed the city of Gallipoli and its city walls, weakening its defenses.

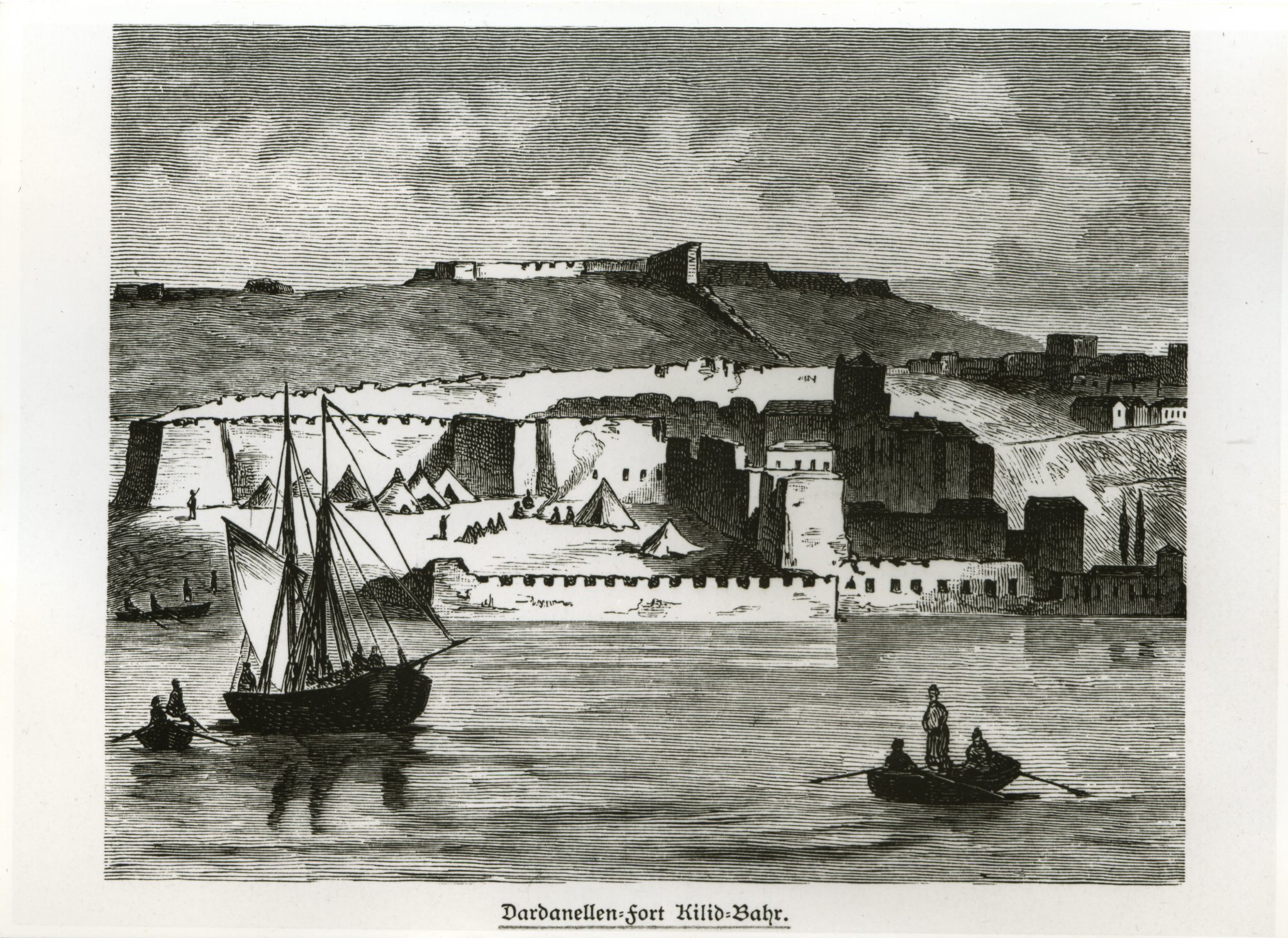

Gallipoli was always a site of particular strategic importance, as it controlled the Dardanelles straits. Already under the Byzantine Empire, it served as a naval base. The Ottoman Turks first captured the strong fortress from the Byzantines in 1354, along with other sites in the area, aided by the above mentioned earthquake. Gallipoli secured the Ottomans a toehold in the Balkans, and became the seat of the chief Ottoman governor in Rumelia. The fortress was recaptured for Byzantium by the Savoyard Crusade in 1366, but the beleaguered Byzantines were forced to hand it back in September 1376.

Gallipoli became the main crossing point for the Ottoman armies moving between Europe and Asia, protected by the Ottoman navy, which had its main base in the city. Sultan Bayezid I (r. 1389–1402) refortified Gallipoli and strengthened its walls and harbor defenses, but initially, the weak Ottoman fleet remained incapable of fully controlling passage of the Dardanelles, especially when confronted by the Venetians. As a result, during the Ottoman–Venetian War (1463–1479) the straits’ defenses were strengthened by two new fortresses, and the Ottoman imperial arsenal was established in Konstantinopel itself. Gallipoli remained the main base of the Ottoman fleet until 1515, when it was moved to Konstantinopel. After this it began to lose its military importance, but remained a major commercial center as the most important crossing-point between Asia and Europe.

Parts of the province were occupied by Bulgarian troops in the First Balkan War, but where recovered by the Ottomans in the Second Balkan War. During the First World War, it was the scene of the Gallipoli Campaign. After the war, the sancak was briefly (1920–1922) occupied by Greece according to the provisions of the Treaty of Sèvres, and became a Greek prefecture. Following the Greek defeat in the Greco-Turkish War of 1919–1922, it returned to Turkey.

Town of Kallipolis / Gallipoli

Ancient Kallipolis was the counterpart of Lampsakos, today’s Lapseki, located on the southern side of the Hellespont (Dardanelles). The city played an important role especially in late antiquity because of its proximity to the capital Constantinople. It was developed into a fortress by Justinian I.

The bishopric of Kallipolis (Kallioupolis) belonged to the ecclesiastical province of Heracleia.

Notables

Sofia Vempo (Σοφία Βέμπο; born Efi Bembou; 10 February 1910, in Gallipoli, East Thrace – 10 March 1978, in Athens); leading Greek singer and actress active from the interwar period to the early postwar years and the 1950s.

Destruction

1914-1915

Diocese of Gallipoli / Kallioupolis

“This Diocese (…) was completely destroyed. Owing to its geographical position it was constantly exposed to the fury of the Turks. Already, during the Balkan War, both the military and civil authorities had succeeded by vexatious requisitions in ruining the trade in the hands of the Christian population; and later, during the European War, the Government, under a pretext of military exigency, forced the inhabitants to evacuate the locality at a few hours’ notice, but took no measures either to protect the abandoned possessions or to succour and maintain the exiled population.

Deportations during the Balkan Wars and the European War.

- BOULAIR.— From the time of the Balkan War the inhabitants of this village suffered first all imaginable evils as a result of successive requisitions, and the arbitrary dealings of the numerous troops concentrated there; then the Turkish Government, under pretext that the village was within the firing line, ordered its evacuation within three hours. Driven by the whips of the gendarmes, the people had to abandon everything they possessed, leave their village and go to Gallipoli. Seven of the villagers who were two minutes late behind the three hours limit allowed for the evacuation were shot by the soldiers. After the Balkan War was over, the exiles were allowed to return. But as the Government allowed only the Turks to rebuild their houses and furnished them besides with timber and every other facility, the exiles were compelled to remain in Gallipoli and later had to share its fate.

- KRITHIA. — A military mission arrived here in October, 1914. Their first move was to surround the village by soldiers with fixed bayonets, and forbade all intercourse between the inhabitants. The soldiers then set to work forcing the evacuation of each house in turn, and under the very eyes of the Commission seized everything they could lay hands on. Stripped of everything they possessed, the wretched inhabitants in despair had to seek refuge in Madhytos and there later on had to share its fate.

- NEOHORI. — This village was evacuated on the 25th March, 1915. The inhabitants had wished to go to Gallipoli, but the military authorities prevented them, telling them that it was not yet time to leave, and when the time came for evacuating the village the inhabitants would be advised, and they should then go, not to Gallipoli, but to the villages of Galata and Bair. This came to pass; 200 dwellings out of 300 houses which composed these villages, and in which the refugees from Neohori had been forced to find shelter, were occupied by Turkish soldiers, and they, by order of their officers, destroyed everything from granary to cellar, so that the poor Christian immigrants were compelled to remain in the open air under continuous rain.

- MADYTOS. — This village was evacuated on the 17th April, 1915, in the space of five hours. After the devastation of their country, and the plunder organized in spite of the promise of Essad Pasha to the Metropolitan, that the property of the Christians would be respected, the inhabitants of Madytos, deprived of everything essential to them, after sojourning four days in the mountains, were embarked and dispatched to the diocese of Cyzic (Pandemia, Pergamos and elsewhere) where the tenth part of them died of the privations and unprecedented ill-treatment they underwent.

- GALLIPOLI. — This town was evacuated on the 19th April, 1915. Two hours’ notice was given to the inhabitants to leave, who after remaining four entire days and nights without any shelter, were embarked on board government steamers. No one was allowed, by order of the police, to take anything away with him. Some took refuge in Panderma, and others in Rodosto. Soon after their departure their houses were plundered.

- TAIFIR, 7. PEKGHAZI, 8. KAUAKLI, 9. GALATA, 10. BAIRI, and 11. ANGHELOHORl.— The inhabitants of these villages were deported in May, 1915, and scattered over the district of Balikesser [Balıkesir].

(…)

Deaths from hunger were daily multiplied. George Cdurbetis, native of Gallipoli, living at Panderma, with his wife Catherini, and his son sixteen years old, were found dying of hunger. They had eaten nothing for a whole week. They were at once given food, but were, however, so exhausted that death resulted very soon.

Cases of rape among women and young girls exiled, as well as their conversion to Islam, were frequent. On the 28th April, 1914 Turkish immigrants penetrated into a Greek farm close to Madytos, and attacked it, killing three of the peasants with their knives. The same day two brothers, refugees, Demitri and Yiassoumi, were beaten to death by the Turks, and their father, Christos Gheorgandidis, was mortally wounded. On the 12th May of the same year, Nic. Pasmada, a native of Taifiri, was shot dead in the jaws. Athanassios Moushetis, also a native of Taifiri, was slaughtered, and Nicolaos Barbazos was mortally wounded. The same fate befell Haralambis Emmanouil on the 31st May. His father was cut to pieces. Georgios Nicolaou, a native of Moshonissi, established in Madytos, was also slain. Christos Persimis, the night guard of Madytos, was dangerously wounded by a Turkish soldier close to the country. On the 26th September, 1914, Anthoulakis Bairlis, was assassinated by two soldiers who forced the door of his hut while he was lunching, and fired at him point blank. On the. 19th October, 1914, Turkish soldiers, having satisfied their bestial instincts on Panayioto Soyaka, a man of seventy, mortally wounded him and threw him into a ditch outside Madytos, where he was found horribly mutilated.

On the 3rd March, 1915, Zacharias Klimas, a native of Krithia, received three stabs in broad daylight. The wounds to his neck were serious. On the 30th October, 1915, three natives of Bairi were cut to pieces at Soussourlouk [Susurluk], while the monk Kyprianos, a native of Moshonissi, was massacred close to Mihalitsi. His eyes were put out. A mason of the name of Sotirios Elissiou, a native of Moshonissi, was put to death. On the 20th December, 1915, Minas Theoharis and his son Constantine were slaughtered by Albanian Turks close to Kermasti. Alexandros Karayiannis and his countryman Panayiotis Kiozelis, native of Taifiri, were murdered.

On the 28th May, 1915, two girls, refugees from Taifiri, near Baloukesser [Balıkesir], Maria Ghoni and Anthoulia Karapanayiotti, were forcibly converted to Mahommedanism by the Authorities. On the 8th July, 1915, the mayor of Kermasti, having fallen in love with Vaitsas Ant. Makri, a refugee of Madytos, and failing to carry her off, revenged himself on her protector, Foti Hadji Nicolaou, by exiling him along with his family to a village eight hours distant from Kermasti.

The Municipality of the village became a house of iniquity, for the refugee women who applied for help to avoid starvation, were outraged. On the 7th April, 1916, the Christian refugees of the villages in the vicinity of Balikesser underwent all kinds of persecution from the Turks. They were refused bread on payment. The women were told that they should become Mussulmen so as not to die of hunger.

In April, 1916, a woman of Madytos was violated by eighteen soldiers successively.

In the beginning of June, Mary Anthoulaki, a native of Bairi, aged twenty, was converted to Mahommedanism at Balikesser, and quite a number of young girls were forced by the authorities at Government headquarters to do the same.”

Excerpted from: Ecumenical Patriarchate: Persecution of the Greeks in Turkey, 1914-1918. Constantinople [London, Printed by the Hesperia Press], 1919, pp. 41-45

“To sum up, there were destroyed eleven towns and villages in the district of Gallipoli, having a Greek population of 24,636 inhabitants(…).” [4]

Armenians

“The fate of the Armenians of the peninsula of Gallipoli was sealed in early April 1915. When the battle for the Dardanelles began, they were temporarily transferred to Biğa and Lapsaki, and, later, deported.”[5]

1919: No return home

“It is well known that this diocese had for several reasons been almost entirely evacuated. Those who had gradually returned to their houses began their usual work.

The murders, however, which were committed by Turkish bands, and the oppressions of the officials seriously impeded their occupations.

On September 4, 1919, robbers went to the sheephold of Ibrahim Tchaoush [Çavuş – ‘sergeant’] beat his shepherd Panayotis of Yeniköy, and scattered his sheep. The authorities on being informed by Ibrahim sent gendarmes who meeting the shepherd and his son Constantine began shooting at them, killing the son and seriously wounding the father, who later died from the wounds he received. No steps were taken by the authorities towards establishing responsibility.

On Sept. 24, Dim. Koutzaris of Anghellohori was found dead. He had been murdered by the notorious brigand Tahir, who disposing powerful means by the local authorities dared informing them himself of Dimosthene’s murder, and afterward prevented the wife from seeing the dead body of her husband.

Tahir was the terror especially of the Greek farmers, and was often employed by the local authorities in scaring the Christians. Forming a volunteers’ corps he went about plundering, beating and murdering. In Taifur he robbed Evanghelos Photius of 100 paper liras and 30 gold. The moudir of Yalova forced through Tahir the Turkish villages to drive away all the Christians living in them. Tahir formally declared that he would massacre those Christians should they not leave the said villages in three days.

On Dec. 6 Dem. Karafotakis and Char. Foundas went from Dardanelles to Lampsakos for the purpose of buying cattle. On the way between Musaköy and Okçilar they were met by 3 Turkish brigands, who robbed them of everything, killing Karafotakis.”[6]