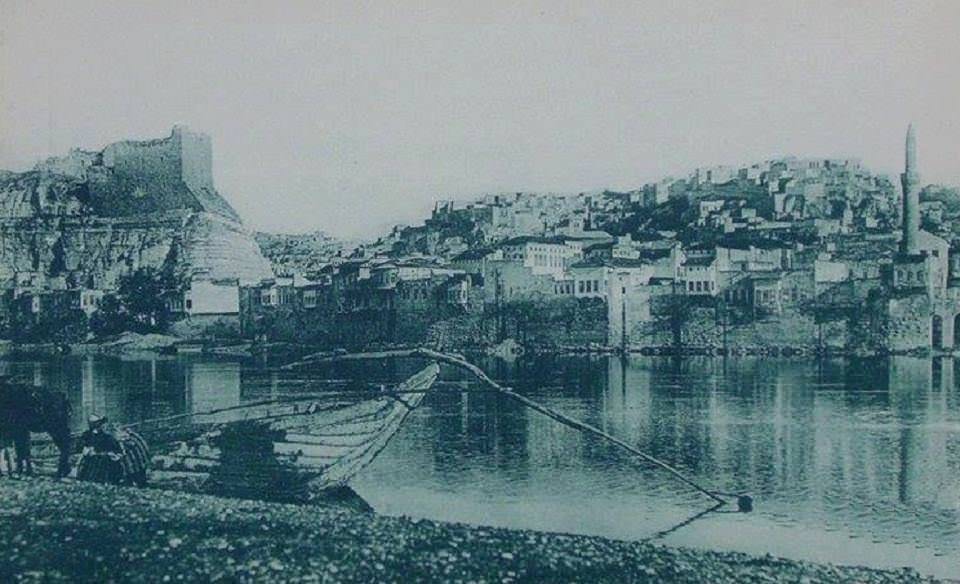

Birecik, on the banks of the Euphrates, was an obligatory way-station to Mesopotamia. The kaza and its administrative seat were named after a fortress built on a limestone cliff on the left/east bank of the Euphrates, “at the upper part of a reach of that river, which runs nearly north-south, and just below a sharp bend in the stream, where it follows that course after coming from a long reach flowing more from the west”.[1]

Toponym

The current placename originates from the Syriac toponym Birtha (‘Palace’), also formerly known as Bir, Biré, Biradhik and during the Crusades as Bile. However, the toponym Birtha is found in no ancient Greek or Roman writer, although Bithra (Grk.: Βίθρα) appears in the account by Zosimus of the invasion of Mesopotamia by Roman Emperor Julian in A.D. 363.

The Greeks at one stage called what is now Birecik by the name Macedonopolis (anglicized also as Makedonoupolis). The city represented by bishops at the First Council of Nicaea and the Council of Chalcedon is called by this name in Latin and Greek records, but Birtha in Syriac texts. A 6 AD inscription in Syriac found at Birecik contains an epitaph of Zarbian, “commander of Birtha.”

Population

According to Ottoman statistics of 1906, there lived 452 Armenians in the kaza of Birecik[2]; according to Ottoman statistics of 1914, the Armenians totaled 1,071.[3] According to the Armenian Apostolic Patriarchate of Constantinople, the Armenian pre-war population of the kaza of 1,600 lived in two localities, maintaining two churches.[4]

Until World War I, about 20% of the population of the town of Birecik were Christians, about one-third of them Armenians.

In 1918, Woodrow Wilson, the American president at the time, requested information on the ethnic demographics of the region. Through an urgent request from the Ministry of the Interior, in late 1918, the mutesarrifat of Urfa reported that there were roughly 26,000 Turks, 2,000 Kurds, and 500 Armenians in the kaza of Birecik, totaling to approximately 28,500 thousand people.[5]

History

It is not known who built the White Fortress of Birecik (Arab.: Qal’at ul-Baydha, Turkish: Beyaz Kale) on a limestone rock on the east bank of the Euphrates River at a firth. It was expanded a total of three times under the Romans (30 B.C. to 395 A.D.), the Crusaders (also called Franks here, 1098 A.D. to 1150 A.D.) and the Mamluks (1277 A.D. to 1484 A.D.)

Bishopric

As an episcopal see, Birtha/Birecik was a suffragan of the metropolitan see of Edessa, the capital of the Roman province of Osrhoene. This is attested in a Notitia Episcopatuum of 599, which assigns to it the first place among the suffragans.

The names of three of its bishops are recorded in extant documents. Mareas signed the acts of the First Council of Nicaea in 325 as bishop of Macedonopolis, The chronicle of Michael the Syrian speaks of a Daniel of Birtha at the Council of Chalcedon in 451, while Giovanni Domenico Mansi calls him bishop of Macedonopolis. The Chronicle of Joshua the Stylite tells of a Bishop Sergius of Birtha who was entrusted by the Emperor Anastasius I Dicorus with refortifying the city, something that must have occurred after peace was made with the Persians in 504. The work was completed by Justinian.

Timur Leng destroyed the town in the 14th century.

Birecik became part of the Ottoman Empire in 1516. It already had a dock at the time that was collecting tolls; the income from the tolls rose dramatically after Suleiman the Magnificent‘s campaign to conquer Baghdad in 1534.

Meanwhile, by 1547 the Ottomans had chosen to make Birecik the site of a major imperial shipyard – the empire’s first in Mesopotamia. Birecik’s geography made it uniquely well-suited to play such a role: by the time it reaches Birecik, the Euphrates has already descended from the Taurus foothills, and the rest of its course consists of gentle slopes and wide valleys.

The first reference to the Ottoman shipyard at Birecik is in June 1547, when an Arab merchant from Basra named Hajji Fayat reported to the Portuguese governor in Hormuz about it. Hajji Fayat specifically referred to the abundance of timber as one of the reasons why the “large and well-populated” town of Birecik was such an advantageous shipbuilding location. Around that time, the Birecik shipyard employed 45 tax-exempt workers. The first documented order for ship construction at Birecik dates from July 1552, when the Ottoman Imperial Council commissioned 300 new ships to be built. Later, as part of an ultimately unsuccessful attempt to reconquer Baghdad in 1629, the Ottoman vizier Hüsrev Pasha ordered 100 new ships to be built at Birecik.

Modern history

Birecik Dam and hydroelectric power plant, part of the Southeastern Anatolia Project, is situated within the district. The Roman city of Zeugma is now drowned in the reservoir behind the dam. Zeugma’s famous mosaics, including the ‘river god’, have been taken to Gaziantep Museum, but some rescued remains of Zeugma are exhibited in Birecik. With its rich architectural heritage, Birecik is a member of the Norwich-based European Association of Historic Towns and Regions (EAHTR).

Destruction

1896: Slaughter and Massive Forcible Islamization

„On January 1, 1896, the Christian quarter of Birecik, in Aleppo vilayet, was attacked by local Muslims, apparently with some soldiers participating and others observing from the sidelines. According to [British diplomat Gerald Henry] Fitzmaurice, who investigated these assaults as well, Birecik’s Armenians ‘were poor and hard-working’ and had little ‘connection with political agitation’ save ‘one or two so-called seditious documents’ that had been ‘found among them.’ The mob invaded Armenian homes and demanded ‘money, trinkets and other valuables on the promise of sparing their lives.’ After valuables were handed over, many adult males were killed ‘with ruthless savagery’ and the houses and churches pillaged. Armenian girls were taken ‘and much dispute and quarrelling occurred in dividing them among the captors.’ The authorities subsequently restored almost all to their families.

Altogether, about 150 Armenians were murdered, and one Muslim was wounded ‘in a brawl over the plunder.’ The dead were thrown into the Euphrates. Armenians attempted to secure their lives by converting to Islam, but even some converts were killed. About 1,600 Gregorian, Protestant, and Catholic Armenians turned Muslim; the Gregorian church was converted into a mosque; and some converts were circumcised. All ‘now wear turbans and are apparently most zealous in their attendance at the mosque,’ Fitzmaurice reported.

But, under Western pressure, the sultan in effect refused to recognize the Birecik mass conversion. For months the local authorities, Western diplomats, and the Sublime Porte waged a struggle over the converts’ souls. ‘My task has been a melancholy one,’ Fitzmaurice wrote, ‘for the fanatical outburst, which had at first some political colouring, gradually . . . degenerated here into a fierce crusade against Christianity. It was conducted with . . . thoroughness [and was] carefully planned.’”

Excerpted from: Morris, Benny; Ze’evi, Dror: The Thirty-Year Genocide: Turkey’s Destruction of Its Christian Minorities 1894-1924. Cambridge, MA; London: Harvard University Press, 2019, p. 96f.

In his report of 14 May 1896 to the French Minister of Foreign Affairs, the French consul Paul Cambon likewise mentioned the forced conversions of Armenians in Birecik:

“(…) the inquiry had established that only those who had converted to Islam had been spared. The Armenians who had become Muslims had had to turn their church into a mosque in order to prove the sincerity of their conversion; now they wear turbans, show themselves very zealous at the mosque and they know if they do not declare that they became Muslims of their own free will, they are in danger.”[6]

1915

„According to information communicated to the American consul Jackson [at Aleppo] by an American missionary, the biggest group of Armenians – that from Birecik – was deported in mid-August [1915] after being invited to convert, and that it was subject to the same ‘methods’ used in Dyarbekir.”[7]