The homonymous capital city of the kaza Bafra is located 47 km NW of Samsun and 80 km SE of Sinope. The town is built on the right-hand side of the Kızıl Irmak River (ancient Gr: Ἅλυς – Halys‘) and along a road that connects it with Samsun and Sinope. Administratively, Bafra was part of the mutesaraflik (sancak) of Samsun and the valilik and subsequent province (vilayet) of Trebizond. Ecclesiastically it belonged to the Diocese of Amaseia.

Toponym

The ancient Greek name variant Paúra was first documented in 1150, the Turkish variant Bafra in 1485.[1]

Population

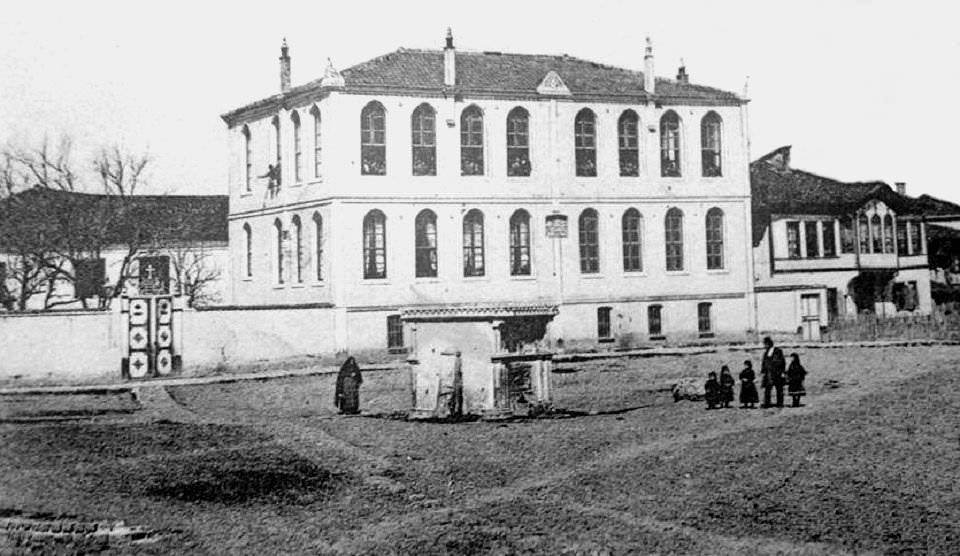

According to one source, in the early 20th century there were 12,000 Orthodox Christians living in the 43 villages of the kaza Bafra. Prior to the First World War, the city had a population of 17,000 people of which 10,000 were Turks, 5,000 were Greek and around 3,000 were Armenian. Aside from the native Greeks, Bafra was also home to Greeks from Kappadokia and other regions of Pontos. The native Greeks and the Kappadokian Greeks were Turkophone, while the Greeks from other regions of Pontos spoke Greek or Pontic Greek. The Greek community had a kindergarten, a 6-grade boys’ school and a 6-grade girls’ school. The metropolitan church was dedicated to Saint Marina while in the Isali (or Sakli) district there was a church dedicated to Saint Basil. The citizens of Bafra applied themselves primarily to the manufacture and trade of tobacco.[2]

In 1914, the Armenian population in the kaza Bafra was limited to the town of Bafra, where 2000 Armenians lived. They were deported at the same time as the Armenians of the city of Samsun. „According to testimony given at the trial of the criminals of Trebizond by Kenan Bey, a court inspector in the region, Bafra’s kaymakam was murdered after he tried to intercede on behalf of the Armenians deported from his kaza. A handful of adolescents nevertheless managed to flee into the Pontic Mountains, where they formed with other young men from the region a group of resistance fighters.”[3]

After the Treaty of Lausanne, the Greek survivors from Bafra were exchanged with the Muslims who came from Kavala, Drama and Thessaloniki regions of Greece and knew the tobacco growing business very well. The number of such immigrants (exhangés) is quite high. In addition, a large population of Albanian immigrants from Kosovo was settled in the Bafra kaza after the Balkan Wars (1912). They still keep the Kosovo culture and their Albanian mother tongue alive. Albanian immigrants have made great contributions to the development of agriculture and horticultural culture in Bafra.[4]

Further information:

A list of the Greek villages of Pontos (or villages where Greeks resided) was compiled by the Center of Asia Minor Studies (Κέντρο Μικρασιατικών Σπουδών) which is based in Greece. The list may exclude some villages which weren’t known at the time the study was completed.

Source: Samouilidis, Christos: The History of Pontian Hellenism. Thessaloniki 1992.

A map with some of the Greek settlements in the kaza of Bafra is just a guide and is hosted by an external source: https://www.google.com/maps/d/viewer?mid=1Yjfol2av6qw0IXdPim4Gehp7AtY&ll=41.646877404579485%2C35.2097226&z=10

Bafra (source: http://www.eskiturkiye.net/3436/bafra#lg=0&slide=0)

“The Annihilation of the Greek Element” in WW1: Expulsions, Deportations, Massacres

“Towards the end of February, 1915, the villages of Ada-tepé [Adatepe], Yelidja, Karakol-near Amassia [Trk.: Amasya]-and twenty other villages of the district of Bafra, were burnt down. Many women and children were murdered. The survivors were (…) deported into the interior and scattered about the Turkish villages, where, yielding to famine and sickness, they died in masses.”[5]

„The Christians of Amassia, Tharchamba [Çarşamba], and Bafra, were expelled at different intervals and the torments undergone by the peasants were indescribable. The Military Governor, Refet Pasha, assisted by Behaeddine Effendi [Dr. Bahaddin Şakir; also Baha Bey; Bahaeddin, Behaeddin], who arrived from Constantinople as a special delegate of the Minister of the Interior [Mehmet Talat], made out lists of the innocent Christians that were to be proscribed. Villages that had been escaped ravages so far were now set on fire, and their inhabitants deported.

The [Greek-Orthodox] Metropolitan, writing under the date of the 27th February, 1917, says:

‘The pretext for this persecution is the presence in the country of about 300 deserters who, in order to keep the gendarmes at a distance, went to Trebizond for arms, which the Russian torpedo boat supplied to them.

‘It cannot be denied that the conduct of the deserters is reprehensible and that the Government has a perfect right to punish them in an exemplary manner. At the same time, however, we fail to understand in what way can the thousands of women and children expelled, as well as the unfortunate villages burnt down, be held responsible in any way, the more so as 95 per cent, at least of their relatives have either died, or are still working the Labor Battalions, or else have duly acquitted themselves of the exoneration taxes. (…)

‘What is being aimed at is nothing less than the annihilation of the Greek element, which, like the Armenian race, they desire to disappear under somewhat similar circumstances.’

At the beginning of February, 1916, eight villages of Bafra, whose inhabitants cultivated the best tobacco in Turkey, were burnt down, and the people were expelled to the Vilayet of Angora. The inhabitants of the eight other villages were expelled to the Interior, but the houses were not destroyed, because the Turks required them to install the Turkish immigrants in as soon as they had been evacuated. The property of the villages burnt or simply evacuated was plundered by the Turks of the vicinity, and the Church vestments were sold in the streets at onerous prices. The tobacco of the evacuated villages was sold by the Government by public auction, and at onerous prices. The sum realized by these sales was appropriated by the Government, while the peasants, who were the owners of the goods, died of hunger in the interior of the country.”[6]

1921/22: Repeated Massacres and Deportations

“(…) much other evidence points to Ankara’s planning for that summer’s destruction of the Greek communities. An Armenian report refers to a July 2 order from Ankara requiring deportation of all ‘adult male’ Christians ‘throughout the interior of Anatolia,’ not merely in the Pontus. Another report indicates that, two weeks later, Ankara ordered the ‘immediate deportation of all Ottoman Greeks’, meaning women, children, and the elderly as well. At the beginning of August, the mutessarif of Bafra told a visiting American naval officer that the deportation ‘of all remaining Greeks, including women and children, had been ordered by Angora.’ That order was apparently reinforced by another, from Nureddin Pasha, who instructed a local governor ‘to proceed with all dispatch to carry out the orders which had been given him or that he would shortly cease to be mutassarif.’ The American officer concluded that this was ‘part of an official plan which contemplates extermination of the Greeks.’ There may not have been an ‘open and avowed policy of extermination,’ but there was evidence of a ‘popular policy’ aiming at ‘Turkey for the Turks,’ as one missionary put it.”[7]

A semi-official statement, issued in Athens on September 8, 1921, reads among others:

“At Bafra the male population were strangled in the church and schools. Osman Agha has burned 18 villages in the region of Zara, and ordered a general massacre in Charki Karahissa[r]. At Arbaya friends of Osman Agha strangled 44 persons in one house alone, and set fire to 42 villages. At Osman Agha’s orders, ten families were strangled in Landik.”[8]

Alternatively to deportation, disarmament of residents and destruction of settlements was another method, as applied in the case of Christian villages “of Bafra, Hafsa [Havza; sancak Samsun], Marsovan (Marzifoun), Ladik and Vizier Keupru [Vezir Köpru; sancak Samsun] in the following manner:

(…) The Turkish Military Authorities then received orders to burn all the mountain villages, and Bakir-Tchaj Maden [Bakir-Çay Maden] (between Marsovan and Vizier Keupru) containing 120 houses, was the first to be totally destroyed, all its inhabitants perishing in the flames. The Christian inhabitants of the surrounding districts fearing that a similar fate awaited them, took refuge to the mountains and their villages were in turn destroyed. In this way about forty villages in the district of Tavshan Dagh [Tavşan Dağ] were burnt.

The villages in the plain were then attacked, but thanks to certain Turks who warned the Christians of their coming fate, a great number succeeded in escaping to the mountains. Turkish Troops then surrounded 67 villages, and with the exception of a few old men and a number who declared that they would embrace Islam and who paid large sums of money, all the men were killed.

With the exception of girls of 14 and 15, and young married women who were sorted out for retention in Harems, all the women and children were deported to the interior of Asia Minor.”[9]

“By summer [1921], the campaign reached the towns. In Bafra, it kicked off with an ancient ploy, according to the Greek Patriarchate. Greek notables were invited to a dinner party at the house of one Efrem Aga, arrested, and murdered. The Turks then rounded up and massacred young Greek men. On June 5 Bafra was surrounded by gendarmes, brigands, and Turkish troops—‘a special corps . . . formed for the purpose of exterminating the Greek element’—who demanded that the men give themselves up. Some hid. The Turks then searched the houses, pillaging and violating ‘the prettiest and best bred’ women. The men were marched off in a succession of convoys. The first headed for the nearby village of Blezli. Seven Bafra priests were axed to death and the rest of the men killed thereafter. One, Nicolas Jordanoglon, gave the Turks 300 Turkish lira for the privilege of being shot rather than butchered with an axe or bayonet. Another 500 men, from a second convoy, were reportedly burnt alive in the church in Selamelik. And another 680 were murdered in a church at Kavdje-son. Five convoys left Bafra that summer. At least two, according to the Greek representative to the League of Nations, were shot up by their escorts near Kavak Gorge, outside Samsun, killing at least 900. The survivors were sent naked, ‘like wandering spirits,’ to Malatya, Charnout, Mamuret, and Alpistan [Trk.: Elbistan]. A western report claimed 1,300 Greeks were murdered in the gorge on August 15 or 16. The government claimed those dead at Kavak had been killed justifiably in battle, after Greek bands supposedly attacked Turks.

On August 8 the Turks collected the Bafran women and girls, ‘stripped and violated them and by torture compelled many to adopt Mohammedanism.’ Those who refused conversion were led off ‘to different unknown places, where many died on the way . . . and the children were slaughtered.’ The only Greeks allowed to stay were the sick people who paid bribes. Some 6,000 Greek women and children were deported from Bafra around August 31 and a further 2,500 on September 19 [1921].”[10]

“Elsewhere around Bafra, the deportations inland were regularly accompanied by mass murder. At Sürmeli, 300 were herded into houses ‘and burnt alive.’ By August all the men in the Ordu region had been exiled. Ten villages, including Bey Alan, ‘bought off ‘ their harassers. But some of their men were later deported, and others fled to the hills. An American naval report stated that, in the Bafra area, ‘as many as 90 percent of deported Greeks have been killed.’ In February 1922 the Turks, directed by Fethi, swept Bafra’s hinterland and captured those hiding in the mountains. The interior minister allegedly offered rewards to soldiers ‘who brought in heads. Five sacks full of heads were brought to him at Bafra; thousands of bodies . . . strewed the woods and plains of Pontus.’”[11]

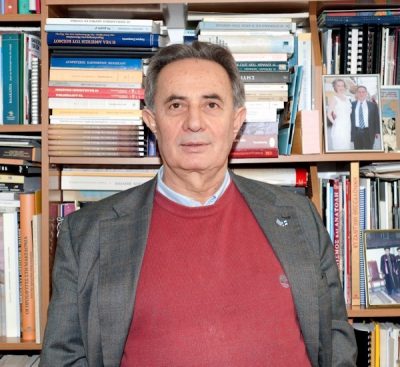

Konstantinos Emm. Fotiadis: Kemalist Deportations from the Kaza Bafra

“The fate of the inhabitants of Bafra and its surroundings was likewise tragic. A first-hand witness, Ioannis Dilmitzoglou, who survived the Bafra massacre and found refuge with 100 others in Medea, Thrace, wrote an account of the plight of the Greeks in the wealthy city of Bafra in Karamanlidika, i.e. the dialect of the Karaman area in Cappadokia:

‘On the morning of Saturday June 5/18, 1921, the city of Bafra was surrounded by troops and armed Turkish locals. Bands of Turks, Albanians and Laz, which were led by gendarmes suddenly appeared in the Christian parishes and demanded that all men surrender to them. They wasted no time in taking their prisoners to the police station, leaving the government agents to destroy their houses. During these crucial moments, the Greek women of Bafra demonstrated unsurpassable courage and self-denial. Even though they underwent terrible torture for several days, not one of them revealed the hiding place of her husband or neighbour. At the risk of their lives, these heroic women hid several of their neighbours in their house, and helped many men escape the Turkish police. However, those who happened to be captured or surrendered out of fear, were immediately confined in the churchyard and later taken across the river without being allowed to carry any extra clothes or food. There, the captives—who amounted to approximately 535 men—were tied back-to-back and led to Suludere in Elezli village, where they were confined in the church. The captives included priests and the notables Murat Celepoğlu and B. Karasavaoğlu. The keys of the church were surrendered to the deputy governor of Bafra. In the meantime, by order of the notables Nevrizi Mehmet and Tirali-zade Mehmet, fully armed locals from neighbouring villages surrounded the church. Initially, the prisoners were stripped of their clothes and robbed of anything they carried. The seven priests were killed with an axe at the entrance to the church. In a truly tragic moment, Father Papagiannis conducted a funeral service complete with an appropriate sermon in anticipation of the fate awaiting all the priests. After the massacre of the seven priests, the troops and the armed villagers climbed up the church’s walls and started shooting down into the crowd. After that, it was the turn of the lance and the axe. The second group was made up of 500 Greeks from Bafra, among them two well-known merchants: Georgios Kouzlou and Kyriakos Solomonoğlu. Kouzlou was killed in the street and his head was delivered to the deputy governor of Bafra. All the others were confined in the church in the village of Selamlik and burnt alive, except for two who escaped to report the event. The third group was made up of 400 army recruits and 280 deportees. This group included some well-known men, including the banker Dimosthenes Dilmitoğlu, Abraham Mavridis, Pantelakis Arzoğlu, Aristides Hatzisavvas, and others, mainly merchants. The place of their martyrdom was the church in the village of Koce-Su. As none of them managed to escape, we do not know how they were executed. The fourth convoy consisted of 35 people, including the merchants Anastasios and Konstantinos Arzoğlu. Having savagely disposed of the greater part of the Greek population, it is not known why the duplicitous Turks considered it necessary to ensure that this last small and insignificant convoy reached its place of exile safely. The Greek deportees arrived at a town called Elbistan, near Maraş, and telegraphed friends.

The acts of horror that took place following the extermination of the men are hard to describe. Some time later, the Turks displaced the women and children, too—needless to say, in the most brutal manner. Now masters of destruction and devastation, the Turks contrived unthinkable methods for the oppression of a people, whose only fault lay in having a different religion and an unquenchable desire for progress. It was this latter characteristic, in particular, which infuriated the weakening Ottoman conqueror. Groups of 1,000 to 1,500 women and children were captured and confined in the yard of the Bafra church. They were kept there for days, denied food or the permission to sell their possessions in order to buy food. The women were stripped, raped, and herded off to Kastamoni. This was usually done on rainy days, as the violent Turks thought those days more appropriate.’

After the devastation of the village of Muamli and another 116 Greek villages, women, children and the elderly moved to Bafra, believing they would find security there. The Kemalists soon proved them wrong. Following the confinement of 3,970 women, children and elders, as well as 150 orphans from the American orphanage, a total of 4,120 people were deported on September 16, 1921: ‘They were escorted by gendarmes, who saw to it that they were stripped at Turtmen Tayi (1,200 metres above sea-level). In this state, and tormented by hardship, they wandered through mountains, villages and cities (Turtmen Tayi, Batman Tayi, Hacihamza, Osmancık, Çorum, Mecitözü of Zara [kaza Koçgiri], Kaynarhan, Inebazar, Cenkel, Turhal [near Tokat], Tokat, Sivas, Tuzla, Tecirhan, Deliktaş, Kangal, Hekim Han) for a total of 70 days. Only 1,270 people out of the initial 4,120 reached Malatya: 130 of the orphans and 2,700 women, children and old people perished on the way of cold, starvation and exhaustion. In Sivas, the Americans took the 20 surviving orphans to the orphanage. Of the 1,270 who reached Malatya, most died of the typhus epidemic that struck the refugee reservations, and others of starvation, the cold, and hardship.’

The eighth convoy of 1,900 people was deported on September 24: ‘Between Deliktaş and Kangal, 310 froze to death, and a further 790 died of various diseases and exhaustion. After a 70-day march, 800 people arrived at Hekim Han. Those who were in the worst state of exhaustion (approximately 400) were left there, and the rest were forwarded to Malatya and Harput, where almost all of them eventually succumbed.’(12)