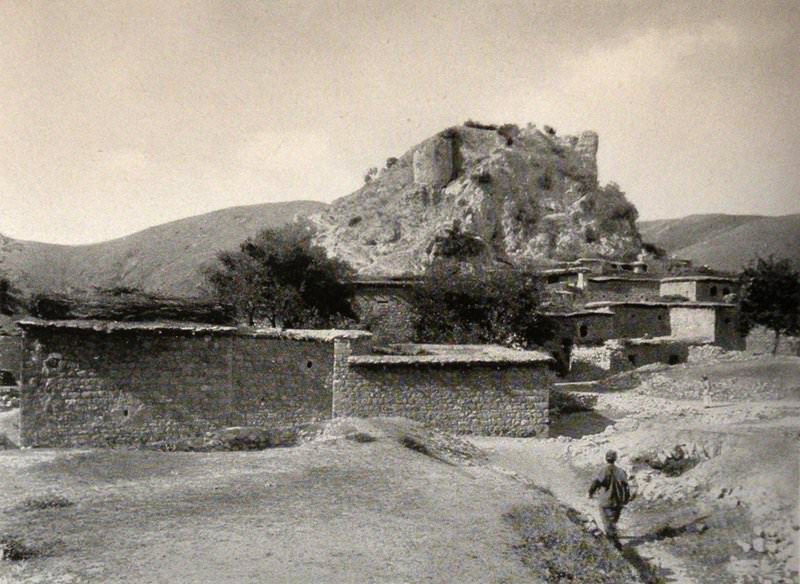

Sasun is a mountainous region in the Armenian Taurus mountain range. The territory of Sasun is mainly composed of the southern foothills of Simi (Sim), Sasno and Salna Mountains. Simsar (Mt Sim; 2689 m), Andokasar (Mt Antok; 2830 m), Tsovasar, Marutasar (Mt. Marut; Maratuk, 2967 m) and other mountain peaks are known. The tributaries of the Tigris flow through the Sasun. The Olor (Aghor) and Baghesh (Bitlis; Zorapahak) mountain passes are of great importance. The climate of Sasun is generally cool and healthy. It has a harsh and cold winter with a thick layer of snow. Winter lasts up to 7 months.

There are forests on the mountain slopes (pine, oak, cedar), followed by meadows. The fauna is diverse, rich in almost all species typical of the Armenian Highlands.

Toponym

Sanasunk, or Sasunk (‘the Land of Sanasar’) which was recorded as the name of the region and principality since the 7th century, includes K(h)ulp, Talvorik, Hazo (Kozluk), Khuyt (Mutki) and Geliguzan (south of Mush) regions in addition to today’s Sason. According to legend, the region takes its name from Sanasar, the son of the Assyrian king (Hebrew šar “king”, Assyrian sar “king”).

Administration

Preserving medieval feudal traditions, in the first thirty years of the 19th century Sasun was de facto ruled by an Armenian prince with the support of the elected council of elders. The Armenians of Sasun not only carried weapons that were forbidden for Christians in Ottoman Turkey, but even produced them. In 1849, after the Ottoman Empire abolished the Kurdish dynasty of the Baghesh (Bitlis) Sheriffs, it annexed Sasun to the Baghesh (Bitlis) Pasha. At the end of the 19th century, the territory of Sasun, then consisting of 10 nahiyes, or a group of villages became part of the sancaks of Mush, Genç, and Siirt in the Diyarbekir Province (until 1880). It became part of Vilâyet Bitlis in 1892.

Population

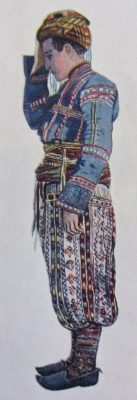

According to the Armenian historian Tovma Artsruni, the people of Sasun – he called them Khutians – lived in deep valleys and caves, spoke different and intricate dialects of Armenian, wore woolen dresses, goat fur and hemp threads to protect themselves from beasts. As a high mountain region, Sasun was a stock breeding area (cattle and sheep).

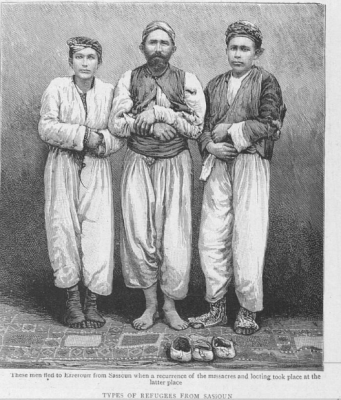

1891 and 1904 the district was razed after two rebellions. At the beginning of the 20th century, Sasun was a partially Armenian settlement area. According to the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople, on the eve of World War I, there lived 24,233 Armenians in 156 localities of the kaza of Sasun, maintaining 127 churches, six monasteries, and 15 parish schools for 1,500 students.[1] However, historical Sasun included parts of the adjacent kazas. Data for the overall Armenian population of historical Sasun in 1915 amount to 60-80,000, which seems to include the refugees from these areas.

In 1925, Sasun again came under attack by government forces.The majority of the population has been deported to various places in Turkey. [2]

History

Formerly Sasun was the eleventh district of Aghdznik (Աղձնիք; Grk.: Arzanene) province of the independent ancient kingdom Armenia (2nd century B.C. – 4th century A.D.). The ancient center was Sanasun Fortress.

From the 9th to the 6th century B.C.the territory of Sasun was part of Urartu, then became part of the Armenian kingdoms of Yervanduni (Orontides; 6th-3rd centuries B.C.), Artashesian (Artaxiad; 2nd-1st centuries B.C.) and Arshakuni (Arsacid; 1-5th centuries A.D.). After the fall of the Arshakuni kingdom (428), Sasun, due to its natural position, maintained its independence, becoming one of the centers of the liberation struggle of the Armenian people. The Mamikonians, who led the struggle against the Arab conquerors in the 7th--8th centuries, fortified themselves in Sasun, among other inaccessible mountainous regions of Armenia. The Tornikians, who descended from the Mamikonians ruled in Sasun from the end of the 8th century. In 851, the inhabitants of Sasun, led by Hovhan Khutetsi, defeated the Arab army in the plain of Mush and killed General Yusup. But in the following year 852 the Arab forces that invaded Armenia massacred 30,000 people in Sasun. Nevertheless, the Tornikians kept Sasun and continued the liberation struggle. The epic Sasna Tsrer (‘The Daredevils of Sasun’) was formed on the basis of Sasun’s heroic struggle against the Arab conquerors.

At the beginning of the 10th century, the Byzantine Empire, in order to facilitate its conquests in Armenia, was able to quarrel with the Tornikians of Sasun and the Bagratunis of Taron. The Tornikians managed to take over a part of Taron. However, after the conquest of Taron by the Byzantines (966/967), the Tornikians, fearing the deceitful policy of the enemy, accepted the rule of the Bagratuni of Ani and cooperated with them. Near the Goat Fortress (west of Mush) the Byzantine army was counterattacked by the military unit, suffering great losses. At the beginning of the reign of Emperor Basileios II (976-1025), a part of Taron, i.e., lands east of the Goat Fortress, remained the property of the Tornikians together with Sasun. The region maintained its independence during the conquests of both Byzantine and Seljuk forces. In the 11th century Sasun was ruled by Mushegh, then by his son Tornik. During the reign of his grandson, Sasun became stronger, the borders were expanded to include most of Taron, some parts of Andzit province, and Ashmushat. In Arabic sources, this powerful prince of Sasun is remembered as a king (‘Malik al-Sanasina’). In 1059 he defeated the Seljuk Turks who invaded Taron. Pilartos Varajnuni, who ruled in the surrounding areas of Commagene, tried to subdue Sasun, but in 1073, Tornik defeated him in the province of Andzit. During the reign of Vigen (1120s-1175), the power of Sasun was strengthened again, the western borders were extended to the province of Degik (in the province of Sophene/ Fourth/Chorrord Hayk). Among others, the Sasun dynasty had kinship relations with the House of Artsrunis of Moks and the Pahlavunis.

13th-15th centuries: During the Mongol rule (13-14th centuries) Sasun was first included in the ‘Greater Armenia’ vilayet consisting of the south-western provinces of Armenia, maintaining a semi-independent state. Hülegü Khan conquered Sasun in the 1260s. According to the Armenian historian Kirakos Gandzaketsi, Sasun was handed over to Sadun II Srtsruni. During the invasion of Timur Lenk (Tamerlane) in 1387, the population of Taron survived the massacre and took refuge in the mountains of Sasun. In the 15th century, Sasun fell to the Turkmen Karakoyunlu, then to the Akkoyunlu, and in the 16th century to Ottoman Turkey, retaining its semi-independent status.

Ottoman Period: Under Ottoman rule, several Kurdish nomadic tribes settled in Sasun. Among them, the non-Islamic Kurds called Beleki (about 40 clans), who lived at the foot of Mount Maratuk (Mt. Marut), spoke Armenian (in the Sasun dialect), attended Armenian shrines, and cooperated with Armenians during the Ottoman government’s encroachments. The Kurds called Sarmntsi-Museti and settling in the Hizan region were in close neighborly relations with the Armenians of Sasun. However, later on the Ottoman rulers, using the backwardness of the Sasun Kurds, succeeded with various promises and privileges (theft of Armenian property, lands, pastures) to incite these Kurds against the Armenians. The population of Sasun resisted the increase of taxation and restrictions through self-defense battles. In the 1880s, residents of Shatakh and Tsovasar village groups, Shenik, Semali, Aliank, Geliguzan and other villages fought against the Ottoman police troops.

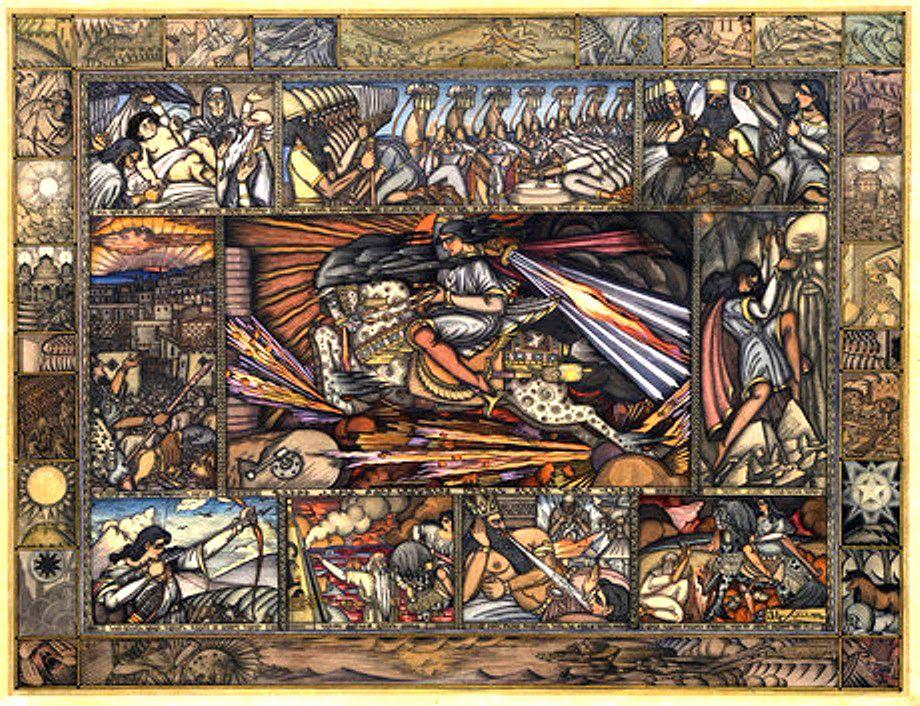

Սասնա ծռեր – The Daredevils of Sasun: Armenia’s Heroic Epic

The epic Սասնա ծռեր (Sasna cṙer – ‘The Daredevils of Sasun’, formed and handed down by anonymous bards (vipasanner) during the 7th-13th centuries, was first recorded in the summer of 1873 by the clergyman, ethnographer and writer Garegin Srvandztiants (1840-1892) after the three-day recital by the village headman Krno in Arnist near Mush (southern Armenia). Thereafter, recordings of over 170 versions were made at different times, of which 70 were published, including a prose retelling (Nairi Zaryan, 1966; Russian edition 1971). The setting of the epic is the mountainous region of Sasun southwest of Lake Van. The epic, divided into four cycles, tells of the rise and fall of the House of Sasun over four ‘generations’ (epochs).

The first cycle is about the twin sons Sanasar and Baghdasar (Balthasar) of the Armenian king’s daughter Dzovinar. The latter had been abducted by the Caliph of Baghdad, but had refused him. After Dzovinar drank from a miraculous spring, she became immaculately pregnant and gave birth to twins. When the caliph sought the lives of the two sons, they fled north and founded a castle and village, which they named Sanasun or Sasun after Sanasar. One day Sanasar dives into the sea and finds there the fairy stallion Jalali, from whose mother-of-pearl saddle hangs the ‘lightning sword’. After taming the animal, he finds the ‘War Cross’ in a nearby church. Thus armed, the brothers set out for Baghdad, kill the caliph and free their mother. Sanasar later marries Deghdzun, the blond-haired daughter of the king of the ‘Copper City’ and has with her the sons Vergo, Hovan and Mher.

The second cycle is about Sanasar’s son, Mher Medz (Mher the Great), who grows up rapidly in the care of his mother and his uncle Hovan (Ohan) ‘of the great voice’, is already a full-grown giant at the age of seven and soon tears a lion in two, which earns him the nickname ‘Lion Mher’. His mother gives him his father’s horse and armor. Married to Armaghan, the daughter of King Theodoros, Mher rules Sasun and defends the country against Mẹsray-Melik, the Muslim ‘prince of Musr’, or Egypt. After the latter’s death, Mher, following an earlier agreement, moves in with Mesray-Melik’s widow Ismil-Khatun. Their union produces a son, Mesray-Melik the younger, who fiercely hates his father. After seven years, Mher returns to Sasun, reconciles with his wife Armaghan, and – as she predicted – dies at the same time as she gives birth to their common son Davit.

Sasuntsi Davit (David of Sasun), the hero of the third cycle, is the dominant figure of the entire work. “Like the Old Testament David who slew Goliath, David of Sassoon is the beloved, national hero, the defiant and self-reliant youth, who by the grace of God defends his homeland in an unequal duel against a titanic oppressor.”[3]

Hovan (Ohan) ‘of the great voice’ takes care of the orphan and sends the boy on the fairy stallion to Ismil-Khatun. When the boy, who has matured into a youth, wants to return to his homeland, his half-brother Mesray-Melik the Younger demands a gesture of submission from him beforehand. Davit refuses and is to be murdered on his way home, but escapes to Sasun. Here he performs heroic deeds as a shepherd and hunter in battle with wild animals and enemies, and finally destroys a strong army sent by Mesray-Melik. Now Mesray-Melik himself, accompanied by his mother and sister, moves against Sasun at the head of a huge force and sets up camp near the fortress. Davit, clad in the armor of his grandfather Sanasar, goes to meet him on the stallion Jalali. From a mountain he falls upon the enemies and defeats them. Then he rides to Mesray-Melik and challenges him to a duel. Through a ruse of Melik and his mother, Davit is initially in great distress until Hovan gives him the right advice from afar in a loud voice. Davit releases Melik’s three blows, which he survives unscathed. At Ismil-Khatun’s request, he himself foregoes two of his three blows, but then kills his mortal enemy with a single monstrous blow, even though he is holed up in a well shaft and has barricaded the opening with 40 millstones and 40 buffalo hides. Davit’s fame spreads rapidly. Princess Khandukht, daughter of the king of Kaputkor, lets him know of her affection through itinerant singers. The hero swings himself on his stallion, stays overnight on the way in Khlat (at Lake Van) with the sovereign Chemeshkik-Sultan, who also falls violently in love with him. The next morning Davit rushes to Kaputkor and marries Khandukht after defeating her in a duel. Chemeshkik Sultan then challenges him to a fight as well. Davit promises to face her in seven days, but forgets and roams the country restlessly for seven years. In the meantime, Chemeshkik-Sultan has a daughter by him, while his wife Khandukht gives birth to a son, the younger Mher.

The latter searches for his father, meets him in a field without recognizing him, and defeats him. The defeated Davit ignorantly curses his own son: he shall remain childless without being able to die. Returning home, Davit notices that his war cross has turned black because he has broken the promise given to Chemeshkik Sultan. He rushes to Khlat but, while taking a bath in the river before the battle, is shot in ambush with a poisoned arrow by his and Chemeshkik Sultan’s daughter. On hearing this, Khandukht throws herself from the castle tower, and both are buried together in the monastery of Maratuk.

The fourth cycle tells about the cruel revenge of the younger Mher on Chemeshkik Sultan and her followers. Then Mher marries Princess Gohar, the beautiful daughter of King Pachik, whom he had previously defeated in a duel. After her death, he travels unsteadily through the lands on Jalali, realizing that lies and injustice prevail everywhere “and the earth has become shaky under the hooves of his horse.” The earth refuses to accept Mher, cursed to immortality by his own father, but finally a voice from his parents’ grave commands him to ride his stallion to a grotto in Ravens’ Rock on Lake Van and wait there until this world has perished. Every year, on the night of Ascension Day, an old shepherd goes to the grotto, finds Mher sitting armed on his stallion, and asks him when he will come back to earth. Mher answers him, “Only after a better world is established.” Every Friday, however, Jalali can be heard neighing in the Ravens’ Rock.

The first cycle was originally probably an independent account of the historical founding of Sasun. The remaining parts reflect the struggle for liberation against the Arab foreign rule (7th – 10th centuries) and the battles against the Egyptian Mameluke army (13th/14th centuries). Thus, the Caliph of Baghdad is mentioned, and other names of Sasun’s foes echo those of Arab rulers and generals. Many figures refer to historical personalities, such as King Theodoros to Prince Toros Rshtuni, who fought against the Arabs in the 7th century, or Hovan ‘of the great voice’ to Prince Hovnan Bagratuni, who instigated a popular uprising against the Arabs around 852 and killed the hostile governor. The figure of Sasuntsi Davit bears traits of both his Old Testament model, the mythical Armenian progenitor Hayk, and the great prince Davit Bagratuni, the champion of Armenian liberation and unification. The folk language is hardly interspersed with foreign influences; vocabulary and grammar show signs of high antiquity and peculiarities of the individual dialects, which often makes comprehension difficult. Numerous elements of Armenian folklore and ancient Armenian mythology have been incorporated into the work. Several attempts have been made to adapt it into poetry, the most popular being Hovhannes Tumanian‘s rhymed version, which has also been translated into English. The epic has similar features to the poetry of neighboring peoples, especially the Iranians, which was written at the same time. Thus, features of the Iranian-Roman light or sun god Mithras are clearly visible in the figure of the younger Mher (from Arab. Mihr – ‘light’). Also, one has pointed out the relationship with Byzantine Acritic Songs (Grk.: Ακριτικά τραγούδια – ‘frontiersmen songs’) and in particular with the most famous of these, the epic Digenes Akritas (‘Two Blood Border Lord’ or ‘Twain-born Borderer’).

Hovhannes Tumanian: Սասունցի Դավիթ – David of Sasun (1902)

I

Great Lion Mher, with his noble pride,

For forty long years ruled Sasun far and wide.

His rule was so awesome that in his day,

Across Sasun’s peaks even birds feared to stray,

Far from the highlands where Sasun was found,

His dreaded fame spread with a thunderous sound,

And praise for the high deeds of Lion Mher

On thousands of lips, in one voice, filled the air.

(…)

III

Then one day, as he thought, his grey eyebrow knit tight,

An angel from heaven, in fiery light,

Came to the prince, feet fixed on a cloud,

Bringing a message, proclaiming aloud:

“Greetings! your highness, O Sasun’s great lord,

Your voice to God’s throne on high heaven has soared

And soon shall he grant you the heir that you seek,

Heed me well, though, prince Mher, great king of this peak,

On the day that the Lord gives effect to your prayer,

Neither your nor your wife shall he suffer to spare.”

“May God’s will be done”, said Mher without sigh,

“Death is our lot; all mortals must die.

But when in this world we’ve a child in our stead,

Through our child we live, although we be dead.”

And then in a flash, the Angel took flight,

And nine months alter and nine hours from that joyous sight,

To Lion Mher a child was born.

And he called his cub David. On that happy morn,

And he summoned his brother Ohan of the Great Voice,

And his realm be bequeathed, no time to rejoice,

To his brother Ohan and his newly born son,

Knowing his days and hos wife’s were now done.

(…)

XI

When it grew dark, they decided to stay,

Ohan the Great Voice had had a long day,

His head on his quiver he rested, then snored.

David however, was restless and bored.

His mind was submerged in a deep sea of thought,

When in the dark a shimmering light caught

His eye and he started and jumped to his feet,

And raced toward the light with his legs fast and fleet,

Bounding he ran to the top of the peak,

Then he glimpsed a white stone in these parts dark und bleak.

The white marble stone was split in the middle,

And a flame burnt bright there, “What a puzzling riddle!”

Thought David as he ran as fast as he could,

To rouse Uncle Ohan to see if he would

Wake up and examine this startling sight.

“Uncle Ohan, enough sleep! Come see the light,

Settled on top of the mountain afar,

Get up, Uncle Ohan, it’s brength as a star,

That bobs up and down on a white marble sheet.”

Ohan crossed himself twice as he rose to his feet.

“Alas, my poor lad, the light that you’ve seen,

Is all that is left on the altar serene,

Of the Church of Our Lady, our keeper and hope,

The convent and church on Maruta’s slope,

Is called Charkhapan, where your dad went and prayed,

Each time he set forth and fierce battle made.

When your father died, God forsook us,

The Melik of Musr then overtook us,

Maruta convent he razed to the ground,

But the altar light pierces the darkness profound.”

XII

When David discovered the convent’s sad fate,

He called to old Ohan, “Dear Uncle, please wait!

I am an orphan, no keeper on earth,

You are my father, though not by birth.

I want to stay here on Maruta’s peak,

Until I’ve rebuilt our convent unique,

Provide me, my keeper, five hundred skilled men,

And five thousand workers to build it again.

Just as it was, we’ve no time to lose,

Send them this week, please don’t refuse.”

Just as he promised, Ohan brought a corps,

Of five thousand five hundred superior

Workers to rebuild the convent on high,

Banging and clanging, it rose to the sky,

Just as it was, in all of its glory,

The Church of Our Lady, a blessed promontory.

The monks to the convent quickly returned,

Chanting soared up again, candles were burned,

David came down from the convent sublime

Restored to the splendor of Great Mher’s time.

Excerpted from: David of Sassoon. By Hovhannes Toumanian (1902). Translated by Thomas Samuelian (1997). Illustrated by Aida Boyajian. Yerevan: Tigran Mets, 1999

Self-Defense and Destruction

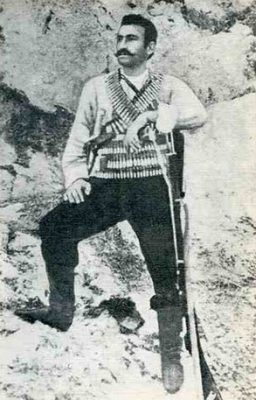

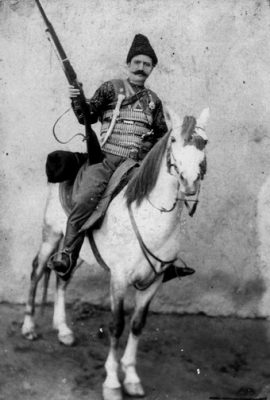

In 1891-1892, at the behest of the Ottoman government, Hamidiye cavalry and Kurdish bandits invaded Sasun, but were repulsed by the inhabitants of Shenik, Semal, Talvorik, Geliguzan, Khotsotsvank, and Shushnamerk. The people of Natatragom, led by hayduk Hovnan, fought heroically. Arabo and his comrades-in-arms stood out. Murad Tamatyan, Hakob Boyajian, Hrayr, Grgon (Grigor Moseyan), Koloz (Hovhannes Kirakosyan), Gevorg Çavuş (‘sergeant’) and others are prominent figures of the Sasun self-defense battles and liberation movement in the 1890s. In 1893, the Ottoman Empire moved regular troops to Sasun. A military zone has been created around the region, and a state of war was declared. The military operations against Sasun were assigned to the commander of the 4th Anatolian Army, Zeki Pasha. The population of Sasun, led by Hakob Boyajian, won a number of victories in the spring and summer of 1894, but eventually lost in an unequal struggle. The Ottoman authorities organized massacres in the occupied territories.

In order to defeat the self-defense forces of Sasun, the Ottoman government launched a new armed attack in 1904 (with 10,000 regular and 5,000 irregular Kurdish troops). Despite their defeat, the people of Sasun rejected the Ottoman government’s demand to leave the mountainous areas and settle in the Mush Plain. In 1896, prominent figures of the Armenian liberation movement such as Andranik Ozanian, Aghbyur (‘Brother’) Serob, Makar of Spaghants fought in Sasun.

During the genocide of 1915, the population of Sasun fought for several months against the 30,000-strong Ottoman army. Out of the 60,000 population of Sasun, about 15,000 were rescued, who migrated to Eastern Armenia with the help of the Russian army and settled in the villages around Ashtarak and Talin on the edge of the Ararat plain.

Raymond Kévorkian: The supposed sanctuary as a death trap (July-August 1915)

“(…) To wipe out the Sasun district’s 80,233 Armenians, who had repeatedly shown, notably in 1894, that they were not inclined to let themselves be killed without a fight, the authorities took a series of measures. They managed to mobilize 3,000 Armenian conscripts, who were officially enrolled in the military transport service but were in fact taken under guard to Lice and then split up into three groups that were executed between Harput and Palu in May 1915.

(…) it was only after the regular troops had finished cleansing the plain of Mush of its Armenians that [the Kurdish irregulars] arrived in large numbers to crush the resistance in Sasun. The operation put in place to eradicate the tens of thousands of Armenians who had taken refuge there resembled a veritable military campaign. The Şeg, Beder, Bozek, and Calal tribes took up position to the east of the mountain district; the Kurds of Kulp, led by Hüseyin Beg and Hasan Beg, dug in to the west, along with the Kurds of Genç and Lice; Khati Bey of Mayafarkin and the Khiank, Badkan, and Bagran tribes took up their positions to the south; finally, the regular army, equipped with mountain cannons, set out to take Sasun from the north. Additional troops were dispatched from Diyarbekir and Mamuret-ul-Aziz to reinforce those already at hand. Ruben Ter-Minasian, one of the two leaders of the Armenian resistance, estimates that the Kurdish-Turkish force encircling Sasun comprised 30,000 troops. In the besieged district were approximately 20,000 natives of the kaza and some 30,000 refugees, who (…) had come from the plain of Mush

and areas to the south. According to Vahan Papazian, the other main Armenian leader, the self-defense effort was mounted to about 1,000 men who had very few modern weapons and a great many hunting rifles.

The first general assault was launched on 18 July 1915. It was renewed the next day by way of Shenek. The attackers forced the Armenians to fall back to their second line of defense on Mt. Atok, where they held firm for several days running. By 28 July, Sasun was running low of ammunition and famine had begun to claim lives, especially among the refugees. On 2 August, the defenders decided to attempt a sortie with the whole population of the enclave. A few thousand Armenians succeeded in crossing the Kurdish-Turkish lines and making their way to the Russian positions in the northern extremity of the sancak of Mush, but the vast majority were massacred, notably in the valley of Gorshik, after the hand-to-hand fighting of the final battles of 5 August, in which the women, armed with daggers, also took part.

A few days earlier, in late July, some of the refugees had gone back down to the plain in desperation. They had convinced themselves that the sultan’s firman (order), in which he granted the Armenians ‘his pardon’ and promised to spare the lives of those who returned to their homes, was no hollow promise. A few days later, the pyres on which the corpses of some of these gullible villagers were burning in Norshen, Khaskiugh, and Migrakom sent up billows of foul-smelling smoke that polluted the whole plain. Other Armenians, a few thousand in numbers, were deported, while a few hundred were ‘taken into’ Kurdish families or seized as war booty by officers. At the time, the Russian lines, which ran through Melazkırt [Malazgirt, Manazkert], were only 25 miles from Mush. It was this distance that the fugitives crossed at night in order to reach the front, when they were not intercepted. In mid-July, Vahan Papazian, Ruben Ter-Minasian, and a few fedayis succeeded in doing so, going by way of the mountain district of Nemrud. Sasun had by this time been emptied of its inhabitants, and is villages lay in ruins.”

Excerpted from: Kévorkian, Raymond: The Armenian Genocide: A Complete History. London, New York: I.B. Tauris, 2011, p. 351f.

The Massacres in Sassoun

“While the ‘Butcher’ battalions of Djevdet Bey and the irregulars of Kiazim Bey were engaged in Bitlis and Moush, some cavalry were sent to Sassoun early in July [1915] to encourage the Kurds who had been defeated by the beginning of June. The Turkish calvary invaded the lower valley of Sassoun and captured a few villages after stout fighting. In the mean-time the reorganized Kurdish tribes attempted to close on Sassoun from the south, west, and north. During the last fortnight of July almost incessant fighting went on, sometimes even during the night. On the whole, the Armenians held their own on all fronts and expelled the Kurds from their advanced positions. However, the people of Sassoun had other anxieties to worry about. The population had doubled since their brothers who had escaped from the plains had sought refuge in their mountains; the millet crop of the last season had been a failure; all honey, fruit, and other local produce had been consumed, and the people had been feeding on unsalted roast mutton (they had not even any salt to make the mutton more sustaining); finally, the ammunition was in no way sufficient for the requirements of heavy fighting. But the worst had yet to come. Kiazim Bey, after reducing the town and the plain of Moush, rushed his army to Sassoun for a new effort to overwhelm these brave mountaineers. Fighting was renewed on all fronts throughout the Sassoun district. Big guns made carnage among the Armmenian ranks. Roupen tells me that Goriun [Koryun], Dikran [Tigran], and 20 others of their best fighters were killed by a single shell, which burst in their midst. Encouraged by the presence guns, the calvary and Kurds pushed on with relentless energy.

The Armenians were compelled to abandon the outlying lines of their defense and were retreating day by day into the heights of Antok, the central block of the mountains, some 10,000 feet high. The non-combatant women and children and their large flocks of cattle greatly hampered the free movements of the defenders, whose number had already been reduced from 3,000 about the half that figure. Terrible confusion prevailed during the Turkish attacks as well as the Armenian counter-attacks. Many of the Armenians smashed their rifles after firing the last cartridge and grasped their revolvers and daggers. The Turkish regulars and Kurds, amounting now to something like 30,000 altogether, pushed higher and higher up the heights and surrounded the main Armenian position at close quarters. Then followed one desperate and heroic struggle for life which have always been the pride of mountaineers. Men, women and children fought with knives, scythes, stones, and anything else they could handle. They rolled blocks of stone down the steep slopes, killing many of the enemy. In a frightful hand-to-hand combat, women were seen thrusting their knives into the throats of Turks and thus accounting many of them. On the 5th August, the last day of the fighting, the blood-stained rocks of Antok were captured by the Turks. The Armenian warriors of Sassoun, except those who had worked round to the rear of the Turks to attack them on their flanks, had died in battle. Several young women, who were in danger of falling into the Turks’ hands, threw themselves from the rocks, some of them with their infants in their arms. The survivors have since been carrying on a guerilla warfare, living only on unsalted mutton and grass. The approaching winter may have disastrous consequences for the remnants of the Sassounli Armenians, because they have nothing to eat and no means of defending themselves.”

Source: Bitlis, Moush and Sassoun: Record of an interview with Roupen, of Sassoun, by Mr. A.S. Safrastian, dated Tiflis, 6th November, 1915. Excerpted from: Viscount Bryce: The Treatment of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire 1915-16; 2nd ed. Beirut 1979, p. 86f.

Ikinci Ferman – The ‘Second (Deportation) Edict’

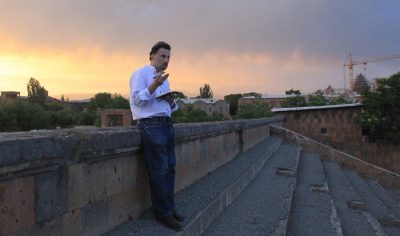

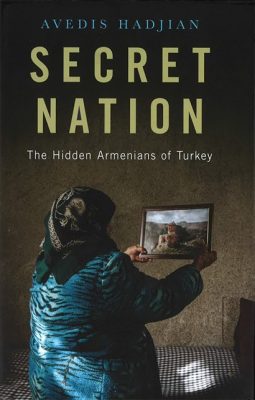

Armenian-Argentine author and journalist Avedis Hadjian estimates that hundreds of thousands of Armenian survivors were forcibly Islamized after 1915, with far-reaching consequences: “The Islamization of Armenians was the means of transportation par excellence to de-Armenize them: They became non-Armenian non-Christians, for even three to four generations later their Turkish or Kurdish neighbors still refer to them as dönmes (converts).”[4] Or as ‘uncircumcised’ (sünnetsizler), as ‘pagans’ or non-Muslims (gâvurlar), but most frequently as filla, the Kurdish mutilation of the Arabic word fallah (farmer, fellache), which in the Armenian context became a swear word and always implies social inferiority.

But those affected also cherish their memories for generations. In Sasun, people of Armenian origin still remember exactly which of their Kurdish and Arab neighbors committed which crimes in 1915 and which tribes ‘just’ robbed and plundered. “We know each other,” an Armenian-born Sasuntsi sums up the situation. The possessiveness of their Muslim neighbors played and still plays a central role in the persecution even of Islamized Armenians. Blood feuds among Kurdish tribes over the plunder of Armenian deportees lasted until the 1980s.[5]

In Sasun, entire Armenian villages were destroyed after 1925 and the population was forcibly relocated to western Anatolia, along with Kurds and Arabs, in the wake of the suppression of a Kurdish uprising (1925-1937). The threat of transfer to the concentration camp of Kütahya by the officials drove hundreds of Sasun Armenians to change their faith at that time.

Attempts by Armenians to reorganize and cultivate their land failed in the long run, as the fate of the Sasun village of Argint (Trk.: Acar, Kurdish Herendi) shows: it became a gathering place for Armenian survivors until half of the village had to be sold to Kurds in 1952. Surrounded and threatened by their Kurdish neighbors, the remaining 30 households of Argint decided to convert to Islam in 1964, which was even reported in the daily newspaper Hürriyet on 7 April 1964. But in the same year, the Kurds burned down the wheat fields of the Armenians, Islam or not. Thanks to the intervention of prime minister Süleyman Demirel and the Turkish military, those who had temporarily fled to Diyarbakır returned to Argint in 1965 and stayed for another 20 years, until the village head Isa capitulated in 1985 to the impoverishment and the exodus of the youth, sold all the property and ‘evacuated’ the remaining inhabitants to Istanbul, so that the youth could be educated there in Armenian schools – but at the price of their final loss of their homeland.

Avedis Hadjian: Survivors’ Testimonies

Avedis Hadjian: Survivor testimonies

“Information on the 1925-37 ‘Sason uprisings’ (as they are known in Turkish historiography) is patchy, but there were two periods: the first rebellion had tapered off by the early 1930s, and the second—possibly the bloodier—started in the spring auf 1935. And in her conflated description, Çoço [Grandma] Siro had got right a major factor in the escalation, if not the actual cause of the second rebellion: a soldier who tried to abuse a woman.

A Turkish gendarme, a member of a tax-collecting party, attempted to molest the young bride of a Kurdish ağa, Teteri Bedik, in the village of Harbak, in a region of Sasun known to locals as Xerzan, and the site where the first rebellion had started in 1925. Even though it is not an officially demarcated geographical unit, Xerzan was a feudal outpost ruled by Kurdish chieftains, who often warred among themselves and resisted central authority. Draft-dodging and tax evasion were rampant, too. (…)

Vanik, Sose, and the çoços (grandmothers) had heard from their elders about a minimal Armenian participation in the rebellion; an Armenian called Sirso (possibly a variant of the Armenian name Sargis or Sergo) fought with the Kurdish rebels, but was caught in the neighboring province of Sırnak in 1938 and locked up in the prison of Kütahya ‘for many years.’ Another two Armenians were captured in the village of Pirşenk: Vartan and Ferman, who handed their firearms to Sose’s father. A young boy at the time, he heard voices calling him from the thickets one night, and these rebels asked him to take their guns and hide them. Both men were apprehended soon after, with their clothes in tatters after crawling through thorny bushes, and were executed in short order.

The Turkish army packed the population of entire villages of Sasun into trains and sent them to internal exile in Western Anatolia in 1938. The renewed Turkish onslaught—this time targeting Kurds—was particularly devastating for the Sasun Armenians who had survived the Genocide and their descendants, as most were permanently uprooted and converted to Islam. While it is likely that these statistics may exist in Turkey’s official records—even if they were reliable—the available figures do not offer a breakdown by nationality or religion.

One of the villages in Xerzan was Gusked, which had remained a pocket of Christian Armenians after the Genocide. Along with Kurdish and Arab deportees, the Armenians from this village were sent to western provinces of Anatolia, mostly Kütahya. The evening before my meeting with Çoço Siro, two other Sasuntsi çoços had shared their recollections from the time of the Second Deportation. They were both from Gusked. One of them, Çoço Maral, was only a small child at the time, but she still recalled it vividly at the time of her interview in 2013:

Two Armenian women and three Muslim ones were killed by soldiers in the 1938 deportation. Kurds were also ransacking Armenians. There were riots and looting. My mother was running, holding me in her arms. But a Turkish soldier shot her, injuring her in the knee. We fell. I think I was four years old at the time. My mother was left behind; I don’t know why. Maybe she hit her head and died. I don’t know. I think they left her there because she was badly injured and could not be saved.

Çoço Maral’s face looked very white under the single bulb burning in her Istanbul apartment, as she evoked with detachment her childhood memories. (…)

Çoço Maral’s family was sent away to Kütahya for ten years. This was when they learned Turkish. Until then, they spoke Arabic and some Armenian. But they were resettled. They were with Muslims: ‘When Arabs and Kurds fought, they would call each other ‘infidel’, but we didn’t meddle with them, nor did the authorities… Had we stayed in Gusked, we would have died in the fighting.’

Her older sister found work in a hospital in Kütahya. (…) Years later, Çoço Maral’s sister ran away with a Kurdish man and converted to Islam. She changed her name to Fatma and died in Adana. Her children and grandchildren to this day do not know she was Armenian. Both sisters maintained some telephone contact, but never saw each other afterwards.”

Excerpted from: Hadjian, Avedis: Secret Nation: The Hidden Armenians of Turkey. London, New York: I.B. Tauris, 2018, p. 86ff.