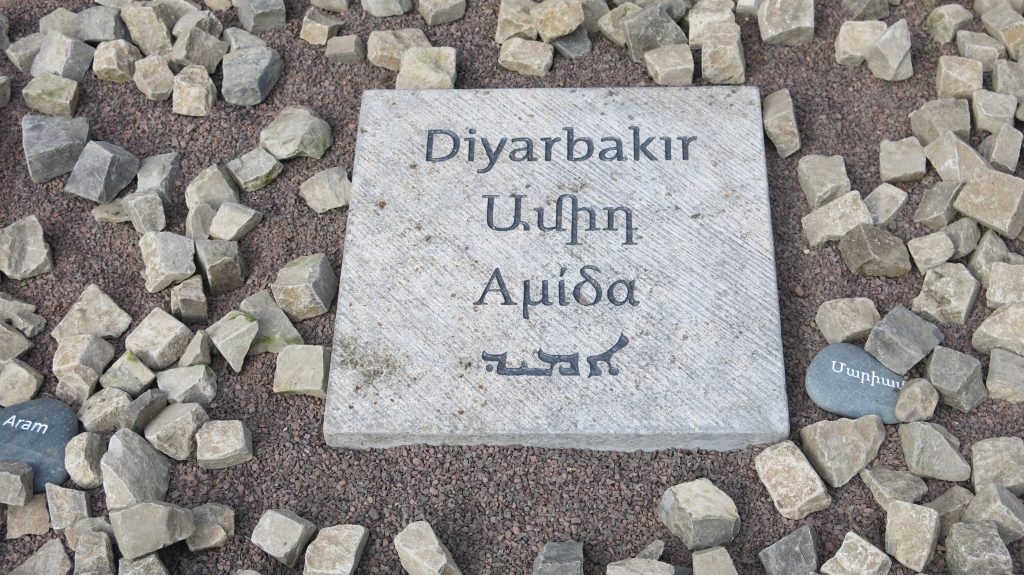

Toponym

Since ancient times, Amida (Armenian: Amid) is the name of the provincial capital city, whereas Diyâr-bekr, meaning the ‘land of Bekr’, is the name of the region and administrative unit since the 7th century. Bekr [Bakr] was one of the main Arab tribal federations during the founding period of Islam.

During the Ottoman period, sometimes the toponym Amid but more often Diyarbekir is used as the name of the settlement. In 1937, by order of Mustafa Kemal, the Diyarbakır writing was adopted. Armenian historians Mateos of Edessa (12th century) and Vardan (13th century) report that the city attributed to King Tigran II (the Great) is Amid. However, it is more likely that the ancient city of Tigranakert (Տիգրանագերտ), which is said to be founded in the 1st century B.C., was not Diyarbekır, but the Erzen fortified city (now Anuşirvan Kale) near Batman Kozluk.[1]

History and Administrative Division

Diyarbekir (the ancient Amida) lies on the western bank of the Tigris. It includes the larger part of the regions, known as Dzop’k’ (also Tsopk – Ծոփք; Ancient Greek: Σωφηνή, romanized: Sōphēnē) and Aghdznik (Aghznik; Arzanena, Arzan) of ancient Armenia. In 94-93 B.C. Dzop’k’ was joined to Greater Armenia (Armenia Maior) by King Tigran II.

Later it was occupied by the Romans and Byzantines. In the year 536 Emperor Justinian made it a Byzantine province, called Fourth Armenia.

In 640 the Arabs conquered Diyarbekir. In 958 the Byzantines succeeded in regaining it. But in 1070 the Seljuk Alp Arslan, and in 1093 the Melik (prince) of Syria took possession of it. In the 13th century it fell to the Mongol domination. After 1335 it was governed by Turkomans. In 1502/3 Diyarbekir was vanquished by the Safavid Shah Ismail I, but the Iranian control did not last long. The Ottomans, taking advantage of the insubordination of the inhabitants during 1515-1517 finally brought Diyarbekir under the direct government of the Sublime Porte.

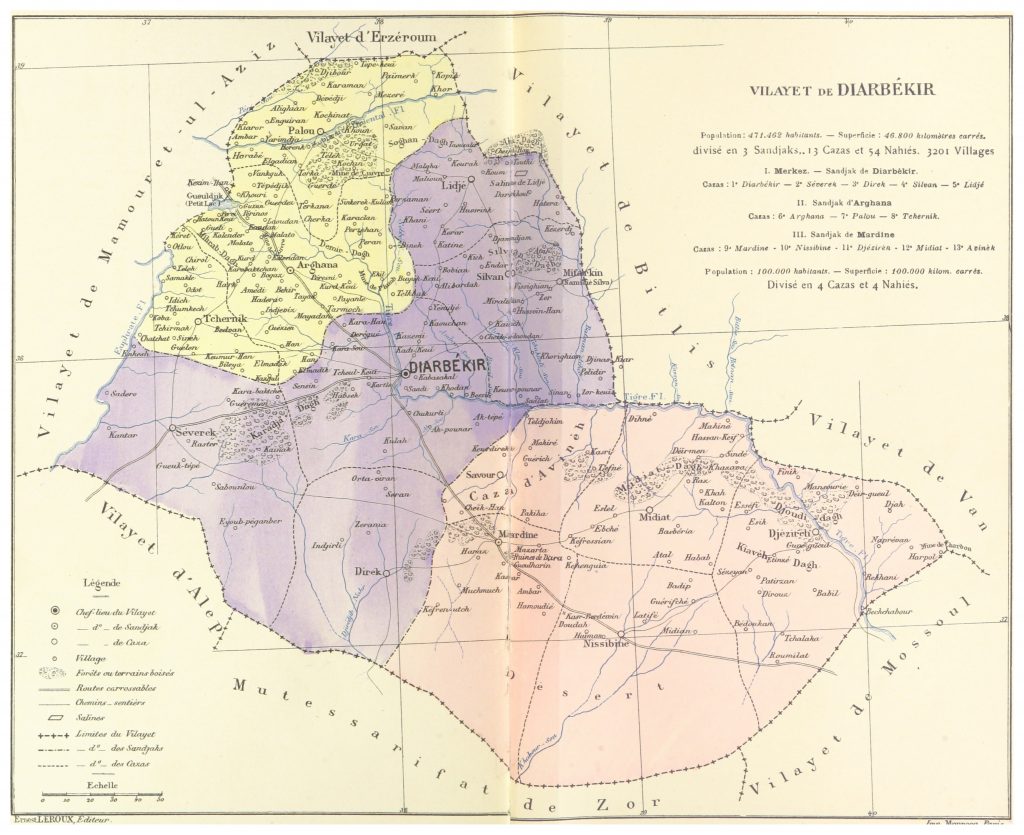

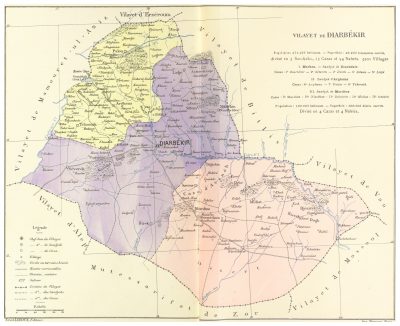

At the beginning of the 20th century the Ottoman Vilayet of Diyâr-ı Bekr (Ottoman Turkish: ولايت ديار بكر, Vilâyet-i Diyarbekır) comprised 46,810 square kilometers. The province emerged as successor of the Eyalet Kurdi (Kurdistan) in 1867 and existed until 1922, including the four sancaks of Arg(h)ana (Trk.: Ergani), Diyarbekir with the provincial capital of same name, Mardin, and Malatya.

In 1867 or 1868 Mamuret-ul-Aziz and the Kurdistan Eyalet merged with the Vilayet of Diyarbakir, but already in 1879–80 Mamuret-ul-Aziz with the sancak of Malatya was separated again and turned into the Vilayet of Mamuret-ül-Aziz. Both provinces, Diyarbekir and Mamuret-ül-Aziz, belonged to the Six Armenian Vilayets of the Empire. The remaining three sancaks of the Diyarbekir province were divided into 13 kazas.

Population

The preliminary results of the first Ottoman census of 1885 (published in 1908) gave the overall population as 471,462. The accuracy of the population figures ranges from ‘approximate’ to ‘merely conjectural’ depending on the region from which they were gathered.

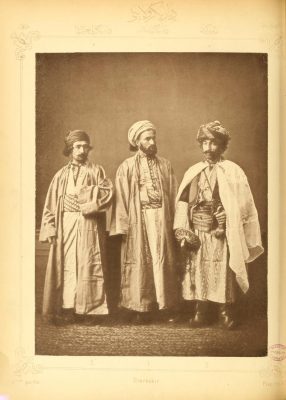

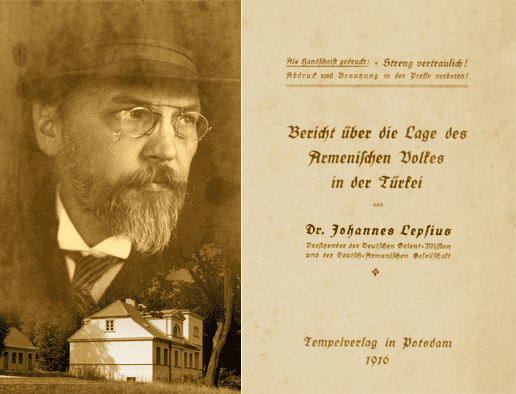

The German theologian Johannes Lepsius gave the following information about the ethno-religious composition of the population in the province of Diyarbekir in 1916: “Of its total population of 471,500 inhabitants, 166,000 were Christians, namely 105,000 Armenians and 60,000 Syriacs (Nestorians and Chaldeans) and 1,000 Greeks. The rest of the population consisted of 63,000 Turks, 200,000 Kurds, 27,000 Kizilbash (Shiites) and 10,000 Circassians. In addition, there were 4,000 Yazidis (…) and 1,500 Jews. The Christian population thus made up a third of the total population of the Vilayet, the Muslim population two thirds.”[2]

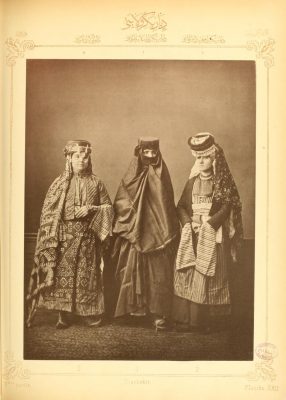

Armenian Population

„In 1914, the vilayet of Dyarbekir had a mixed population consisting of Kurds, Orthodox and Catholic Syriacs and Armenians. The Armenians were basically concentrated in the northern and northeastern parts of the vilayet, the southernmost zones of the territory they inhabited; they lived in 249 towns and villages, with a total population of 106,867, according to the census of the Constantinople Patriarchate. The Armenians of the northeastern kazas – Lice, Beşiri, and Silvan – were Kurdish-speaking. Their tribal mode of life suggests that they had adapted to their predominantly Kurdish environment. These regions, with a dense Armenian population that largely escaped the control of the central authorities, had been a source of profound irritation for the CUP [Committee for Union and Progress, alias Young Turks] from a very early date. In May 1913, French diplomatic sources observed an upsurge in the number of exactions perpetrated against the Armenian population; the violence of these acts can only have come about as the result of orders from the higher echelons.”[3]

Trades and Professions of Armenians

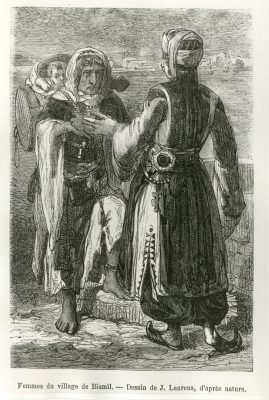

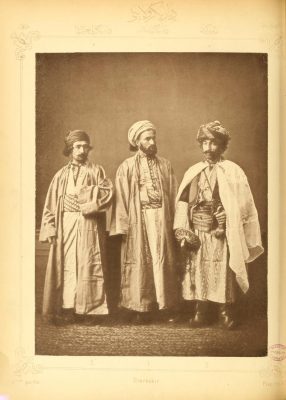

“In the second half of the 19th century, in the province of Diyarbakir, especially in the towns of Diyarbakir and Mardin, trade and industry were in a flourishing state. The main productions were silk and cotton textiles, articles of copper and earthenware, and morocco leather. The Armenian took an active part in local trade and manufacturing as skilled craftsmen merchants and artisans. Martiros Attarian[4] was a famous manufacturer of Turkish linen, Tchavrashian was a well-known tailor, while architecture was practiced almost entirely by Armenians. (…)

Members of the Armenian community were also occupied in different professions, especially in law, medicine and pharmacy, of whom the names of Boghos Efendi Der-Gabrielian (lawyer, fl.c. 1890), Karapet (Garabed) Efendi Dabaghian (lawyer, flc.c. 1890), Kirakos Efendi Enovchian (lawyer, fl.c. 1890), Dr Tchibukdjian (municipal doctor, fl.c. 1892), Dr Artin Helvadjian (army physician, fl.c. 1890), Yakob Hekimian (municipal chemist, fl.c. 1892), and Artin Aghkekian (municipal chemist, fl.c. 1892) can be mentioned.”

Excerpted from: Krikorian, Mesrob M.: Armenians in the Service of the Ottoman Empire: 1860-1908. London: Routledge, 1977, p. 21f.

Greek and Syriac Participation

“The public life of the province was, on the whole, directed by Turks and Armenians, these latter being in the majority among the Christian population. However, to a certain extent Greeks and Syrians also made some contribution. Greek officials, mainly in the centre of the ‘sancaks’ of Diyarbakir, Mardin and Ergani, participated in judicature, finance, political administration, technical affairs and public health. It has to be noticed that in the army Greek doctors, surgeons and chemist were more numerous than the Armenians. Syrian officials were to be found throughout the province and particularly at Mardin, but there were not as many Syrians as Greeks. They were usually to be found in the administrative and municipal councils, but a few held posts also in judicature and finance.”

Excerpted from: Krikorian, Mesrob M.: Armenians in the Service of the Ottoman Empire: 1860-1908. London: Routledge, 1977, p. 22f.

Destruction of the Christian Population

November-December 1895: The First Massacre

Tensions between the Kurdish majority population and Armenian Christians intensified in the early 1890s, caused by the arbitrary ‘taxation’ of Christians by the Kurds. These tensions culminated in 1894 in the northeastern neighboring province of Bitlis, where the Armenian majority population of Sasun rose up against double taxation by the Ottoman state and the Kurds; this peasant rebellion was brutally crushed by regular and irregular Ottoman forces. The violence also spread to the province of Diyarbekir.

„In summer 1893, after a severe two-year famine and after paying tribute to two local tribes and taxes to the government, the situation became ‘insupportable’ when Kurdish tribes from Diyarbekir, the Badikanli and Bekiranli, entered the town and demanded additional tribute. When the Armenians refused, the Kurds raided nearby villages. Armenians then mounted counter-raids. (…)”[5]

“After the 1894 massacre at Sason and subsequent appointment under European pressure of a commission of inquiry, Thomas Boyajian noted rising anti-Christian sentiment in Diyarbekir, where he was vice-consul for Her Majesty’s Government. He felt the ‘lower classes’ were especially afflicted. (…)

The pent-up rage in and around Diyarbekir exploded on November 1. Turks and Kurds rioted for three days, ‘absolutely unchecked by the authorities.’ Armenians were killed in the bazaars, the streets, and their homes. About 1,000 Armenians and 160 Assyrians [Syriacs] died, and some 2,500 shops and 1,700 homes were pillaged or burnt.”[6]

The French vice-consul Gustave Meyrier drew up a precise list of violent acts in his report of 18 December: The Armenian community came out far ahead with more than 1,000 dead counted in the city of Diyarbekir alone. All Christian communities were affected regardless of faith:

The French vice-consul Gustave Meyrier drew up a precise list of violent acts in his report of 18 December: The Armenian community came out far ahead with more than 1,000 dead counted in the city of Diyarbekir alone. All Christian communities were affected regardless of faith:

“Gregorian Armenians: 1000 dead, 250 wounded, 1,500 homes looted, 2,000 looted and burned shops. Armenian Catholics: 10 dead, 1 wounded, 36 homes looted, 65 looted and burned shops. Jacobite Syrians [Syriac Orthodox]: 36 death declared, 150 actual death, 11 wounded, 35 homes looted, 200 looted and burned shops. Catholic Syrians [Syriac Catholics]: 3 dead, 1 wounded, 6 homes looted, 30 looted and burned shops. Chaldeans: 14 dead, 9 wounded, 58 homes looted, 78 looted and burned shops. Greeks: 3 dead, 3 wounded, 15 homes looted, 15 looted and burned shops. Protestants: 11 dead, 1 wounded, 51 homes looted, 60 looted and burned shops.’

167 Syriacs were assassinated, if we add Syriac Orthodox, Syriac Catholics and Chaldeans together. We should also add to this number a few Protestants, just as it is also certain that same Armenian-speaking Syriac victims were counted as Armenians.”[7]

The terror lasted another 46 days after the first events, until an official inquiry committee arrived from Istanbul at the request of the European governments. The Christians were again systematically disarmed.[8] “Still, few Christians managed to defend themselves with the few weapons they had and they successfully protected some neighborhoods. The streets were narrow and easily defendable, but no one could get out of the city. The Capuchin priests’ monastery took in more than 3,000 Christians of all denominations, and more than 1,500 had found refuge at the French consulate.”[9]

“The massacre was followed by Kurdish attacks on nearby Armenian and Assyrian [Syriac] villages and towns, including Nisibin, Midyat, and Siirt, and on two Yezidi villages. In most, churches were burned and priests murdered. Mardin was assaulted by Kurds on the ninth, eleventh, and sixteenth of November, but each time the town’s Muslims and Christians made common cause to drive them back. Muslim leaders feared that the Kurds would also sack Muslim homes, and some Muslims came from Assyrian stock, fostering bonds of sympathy. Assyrian villages around Mardin were raided, and some, such as Tell Armen and Al Kulye, completely destroyed. The Syriac inhabitants of Qalaat Mara fled to the nearby Za’faran Monastery (Deyrulzafaran), which they successfully defended against a Kurdish force, perhaps with the assistance of soldiers.

[Vice-Consul Cecil] Hallward estimated that 800 or 900 Christians were murdered in the villages around Diyarbekir, and 155 women and girls were carried off by Kurds. By mid-March 1896, ‘perhaps twenty’ girls had been recovered, some having ‘declared themselves Moslem.’ This may have been a smart move, for themselves and their families. After an abducted Assyrian from the Silvan district was ‘restored to her husband’ unconverted, Kurds proceeded to kill ‘both her husband and father-in-law.’ In many of the region’s villages, massacre survivors were forced to convert, and churches were converted to mosques. In Lice all of the men were circumcised.

(…)

Altogether, in Diyarbekir vilayet, some ‘8,000 appear to have been killed,’ Hallward wrote. He put the number of Muslim converts at 25,000. ‘Upward of 500 women and girls’ were abducted. ‘One of the principal elements of disorder here is the so-called ‘Young Turkey’,’ Hallward added, referring to the party that, in 1908, would topple Abdülhamid’s rule. Among them were ‘some four of the worst characters in the place.’ Hallward said they regarded the situation as ‘revolutionary’ and had sought to provoke disorder in order to topple the sultan.

The French ambassador reported that the 400 Armenian families still living in the Diyarbekir area after the massacres were in dire need, but the authorities were withholding aid. The local priest had refused to sign a telegram to the sultan blaming the Armenians for inciting the violence they had suffered. Until he did so, the government wouldn’t help.“[10]

Forced Islamization

“The fate of converts was mixed. Writing from Diyarbekir in spring 1896, Hallward claimed, ‘The majority of the forced converts . . . have now returned to Christianity.’ But in the Silvan area, he added, ‘a good many . . . remain Turk through fear.’ Still others may have felt that, in the long term, even after anti-Christian passions abated, wisdom dictated continued adherence to Islam. To be sure, the vast majority of Christians in the eastern provinces, despite the turbulence and threats, never converted.”[11]

Deportations and Massacres in WW1

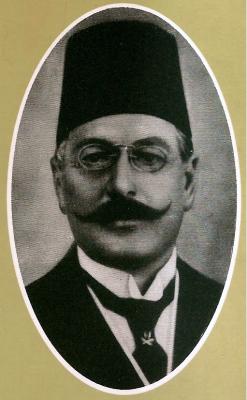

The Butcher of Diyarbekir: Governor Mehmet Reşid Şahingiray

Under the anti-Christian vali Dr Reşid (Reşit) Şahingiray (1873-6 February 1919) the elimination of the Armenians expanded into a general destruction of Christians. The German vice-consul Walter Holstein reported on 13 June 1915 from Mosul:

[…] In the districts of Mardin and Amadia [Diyarbekir] the situation has evolved into a real Christian persecution. For the government must surely be held responsible: apparently the Christians here are outlawed; one of many cases would be the one of the old and revered Chaldean Patriarch – I have just come back from visiting him – who was summoned without reason to the war tribunal by an ordinary policeman. From the side of the government[12] this is a tasteless provocation of Christendom today.

A government like the one today, whose civil servants frequent the lowest females and who direct the execution of their office after the wishes of whores, should not provoke like that at this moment.

Soon we will see the most violent uproars everywhere, if the central government does not change its program of Christian persecution. The massacres on the Armenians should be ended immediately.[13]

Vice consul Holstein demanded Reşid’s immediate impeachment. As a result of German diplomatic protest the Minister of the Interior, Talat, reprimanded Reşid in his telegram of 12 July 1915 not to apply the ‘penalties’ [tedabir-i inzibatiye] on other Christians than Armenians, because such an inclusion could be ‘harmful to the country’.[14] Several scholars inferred from this telegram that the inclusion of Aramaic speaking Christians remained limited to the Diyarbekır province. However, such an assumption does not stand proof. Reşid not only remained in office, but allowed to continue massacres and deportations of Christians far into September 1915.[15]

Quite impressed by Reşid, the Venezuelan mercenary Rafael de

Nogales described the governor as “a man of some fifty years, of distinguished bearing, educated in Paris and belonging to a very aristocratic family of Stamboul”[16]. In his conversation with Nogales in late June of 1915, Reşid accused Minister of the Interior Talat of being the real author of the Armenian extermination: ” (…) he [Reşid] gave me to understand also that, in regard to the extermination of the Armenians of his vilayet, he had merely obeyed superior orders; so that the responsibility for the massacres perpetrated there should rest not with him, but with his chief, the then Minister of the Interior, Talaat Bey – one year later the Grand Vizier, Talaat Pasha. Talaat had ordered the slaughter by a circular telegram, if my memory is correct, containing a scant three words: ‘Yak – Vur – Oldur,’ meaning ‘Burn, demolish, kill.’”[17] Nogales adopted this trivialization by calling Reşid a “mere hyena, who killed without ever risking his own life”.[18]

“Under Vali Çerkes [Circassian] Reşid, Diyarbekir vilayet became one of the bloodiest Christian killing fields of 1914–1916. Reşid murdered Armenians, Greeks, and Assyrians without discrimination. He also executed subordinates who opposed or evaded his directives. These included the kaymakams of several provincial towns, Derik, Lice, and Beşiri, and possibly the mutesarrif of another, Mardin. The vilayet’s health inspector, Dr. Ismail Bey, openly opposed killings of Christians and especially the murder of babies and children; he was dismissed and packed off to Constantinople. Unlike many officials who protested innocence or justification, it appears Reşid knew what he was doing and made no excuses. At the end of the war, he committed suicide rather than submit to Ottoman and British intelligence agents hard on his heels. By that point more than 100,000 Armenians and some 60,000 Assyrians from Diyarbekir vilayet were dead. These numbers do not include thousands of unfortunate nonresidents who happened to be in the vilayet at the wrong time.”[19]

In Ankara, a boulevard was named in honour of Dr Mehmed (Mehmet) Reşid (Reşit) Şahingiray.

Destruction: “In number and nature beyond all the crimes”[20]

“Conditions in the vilayet rapidly deteriorated after the start of World War I. On August 19, 1914, Diyarbekir city’s bazaar, whose proprietors were mainly Armenians and Assyrians, burned to the ground. Thomas Mugerditchian, the British pro-consul in Diyarbekir, claimed that the fire was an arson proposed by the city’s CUP parliamentary deputy, Feyzi Bey Pirinççioğlu, and carried out by police officers after Muslim shop-owners had been warned to stay away and clear out their merchandise. [Governor] Hamid Bey had Gevranlizâde Memduh Bey, the chief of police, arrested and banished for his suspected role. Crusading against an official conspiracy only made CUP officials more wary of Hamid. Not long after the fire, he was removed from office, and, on 28 March 1915, replaced by Reşid.

As an arch-nationalist with military training, Reşid was well suited to enact the CUP plan for Armenian destruction. (…) He brought to Diyarbekir dozens of shady characters, whom he immediately placed in charge of the local gendarmerie. He also immediately joined forces with Pirinççioğlu to coordinate the massacres. Testimony from an Ottoman official indicates that Feyzi had attended secret CUP Central Committee meetings in Constantinople in which the annihilationist policy was discussed and was then sent back to Diyarbekir to help orchestrate the campaign. He also recruited Kurdish and Circassian chieftains to the cause and offered to pardon perpetrators.

Along with the new police chiefs, Ruşdi and Veli Necdet (Nejdet), Feyzi set up a local branch of the Special Organization [Teşkilat-i Mahsusa]. According to a detailed report by one eyewitness, the three men gathered the ‘worst specimens of thieves, brigands, murderers, deserters,’ fashioned them into eleven battalions, and appointed themselves commanders. With Reşid, the group established a Superior Council, which met regularly to discuss operational details. Weeks before the national deportation plan was set in motion, Reşid and the council had produced their own, approved tacitly by Talât. The strategy was set in motion on 16 April, when local units of the Special Organization surrounded the Armenian quarters in Diyarbekir, searched for arms, and arrested 300 young men. (…)

While Diyarbekir’s Armenian notables were being disposed of, Reşid set his sights on Mardin, the province’s picturesque second city and a center of multisectarian Christian life. But Mardin’s mutesarrif, Hilmi Bey, refused to take part in the extermination. Mardin Armenians, he argued, were loyal citizens. Most were Catholic and spoke Arabic rather than Armenian; they had little in common with rebels in other regions. In spite of Hilmi’s guardianship, Mardin’s Christians sensed the coming storm. On 1 May the Armenian Catholic archbishop, Ignatius Maloyan, sent a letter to his congregation naming his successor and proclaiming, ‘I have never broken any of the laws of the Sublime Porte. . . . I urge all of you to follow my example. . . . Pray to [God] to give me the power and courage . . . to carry me through this final time and the trials of martyrdom.’

Starting on 3 June, Reşid’s men began rounding up Mardin’s Christian leaders. Hundreds of Armenian, Assyrian, and Greek notables, including Maloyan, were interned in the citadel or in underground dungeons outside the city. A week later, after torture and forced confessions, the notables were dispatched on the road to Diyarbekir. Muslim townspeople ‘jeered and children threw stones’ at the men as they were paraded out of Mardin, chained or roped together in batches of forty. Last in the procession was Maloyan, bareheaded and barefooted. On the road, Gevranlizâde Memduh Bey—the former chief of police, set free by Feyzi Bey after the bazaar fire and rehired by Reşid—read out what he claimed was an imperial edict condemning the detainees to death. Maloyan apparently improvised a religious service and then was marched off alone and executed. The rest followed. More convoys left Mardin on June 14; July 2, 17, and 27; and August 10. Almost all of the deportees were Armenians. Most were stripped naked and murdered soon after leaving town, although some apparently reached the Syrian Desert. The caravan of June 14 included Assyrians, but soon after setting out, many of them were returned to Mardin unharmed, probably on instructions from Talat.

In general, the reprieve of non-Armenian Christians was an illusion. Clemeny was short-lived, and, even while the order was supposedly in force, local officials regularly ignored it without penalty. One need look no farther than Tur Abdin, an area east of Mardin including the heavily Christian kazas of Midyat, Beşiri, Cizre, and Nisibin (Nusaybin). On June 15 the Gregorian, Armenian Protestant, and Syrian Chaldean males of Nisibin were rounded up and executed. A few days later, the women were slaughtered, some in a stone quarry. The Syrian Orthodox community was left untouched until August, when they, too, along with their bishop, were murdered. Only a few Assyrians managed to escape to Mount Sinjar. On August 24 Muslim militiamen dealt with Cizre’s 2,000 Christian inhabitants, most of them Assyrians. Before then, the Christian communities had managed to buy off local powerbrokers. But, when the time came, the adult males were taken and murdered on the banks of the Tigris. The women and children were taken to a Dominican monastery and an Assyrian church, where they were robbed and raped. Some were then taken away by Muslims; the rest were murdered. (…)

By October [1915] virtually the entire Armenian population of Diyarbekir had been either murdered or deported, and, in total, Christian communities lost between 70 and 80 percent of their members. Most of the deportees were killed in valleys around Diyarbekir city—24,000 in Devil’s Valley (Şeytan Dere), between Diyarbekir and Urfa, alone. (…)

According to Talât’s calculations, there were 56,000 Armenians in the vilayet before the war and fewer than 2,000 in 1917. Yet in a telegram sent on September 15, 1915, Reşid claimed to have deported 120,000 Armenians. Historian Uğur Ümit Üngör suggests that altogether some 150,000 Christians were murdered in the summer of 1915 in Diyarbekir vilayet, more than half of them, and perhaps as many as two-thirds, belonging to various Assyrian sects [Syriac denominations].”

Experted from: Morris, Benny; Ze’evi, Dror: The Thirty-Year Genocide: Turkey’s Destruction of its Christian Minorities 1894-1924. Cambridge, MA; London: Harvard University Press, 2019, p. 199-204

The French Dominican missionary, scholar, writer and poet in Sureth, Jacques Rhétoré, “estimated that 200,000 Christians were killed within the province of Diyarbekir. Of that number, 144,185 (amounting to 82 percent of the Christian population) were native residents and about 55,000 were outsiders who had been killed when their deportation caravans were attacked. Victims came from all faiths, and the largest groups were from the Syriac Orthodox church with 60,725 deaths and the Gregorian Armenians with 58,000 deaths.”[21]

Spring 1915: Eliticide

Based on reports by German officials, the German Johannes Lepsius summarized the massive arrests, deportations and massacres of prominent Armenians and Syriacs as follows:

“In Diyarbekir in the spring of 1915, at the instigation of the Vali [governor], a commissioner was appointed ‘to study the Armenian question’. The president of this commission was Mektubci [secretary in charge for correspondence and archives] Bedri Bey. In addition to him, the commission included the former secretary of Hoff Bey, the deputy Pirenççi-Zade-Faizzi Bey [Feyzi Bey Pirinççioğlu], Major Nüci Bey, the Binbaşı (captain) of the militia, Şevki Bey and the son of the Müfti (judge) Şerif Bey (cousin of the deputy Pirenççi). They started their activity by persecuting the followers of Dashnaktsagan [Armenian Revolutionary Federation – ARF]. Their first victims were the chairman of Dashnaktsagan and 26 Armenian notables, including the priest Alpiar. They were captured, tortured in prison and then murdered by Osman Bey and police Müdir Hüssein Bey. The young wife of the priest was raped by ten zaptiehs and martyred almost to death. For about 30 days, a large number of Armenians were arrested everyday and then killed in prison at night. Two Armenian physicians were forced to certify that the cause of death of all those murdered was typhus.

Dr. Vahan was arrested with ten other notables claiming to be banished to Malatya. On the way there they were all killed. In order to take part in the planned massacre, a notorious Kurdish marauder, Omar Bey from Jezire [Trk.: Cezire] (…) was brought to Diyarbekir by the deputy Faizi Bey with the promise of impunity.

Between May 10 and 30 [1915], another 1,200 of the most respected Armenians and Syriacs from the Vilayet were arrested. On May 30, 674 of them were loaded onto 13 keleks (rafts carried by inflated tubes) under the pretext of being taken to Mosul. The transport was led by the adjutant of the Vali with about 50 gendarmes. Half of them distributed themselves among the boats, while the other half rode along the banks. Soon after the departure, they took all the money, about 6,000 Turkish pounds (110,000 marks) and the clothes from the men. Then they threw them all into the river. The gendarmes on the bank had the task of killing all those who tried to save themselves by swimming. The clothes of those murdered were sold at the market in Diyarbekir. The above-mentioned Omar Bey also participated in the killing.

At the same time, about 700 Armenian young men between the ages of 16 and 20 were allegedly drafted into the military and hired to work on the street Karabahçe-Habaşı, between Diyarbekir and Urfa. During this work, these labor soldiers were shot down by the zaptiehs guarding them. The commanding officer Onbşı (NCO) boasted of his heroic deed that he had managed to shoot down the 700 defenseless Armenians scattered on the street with only five zaptiehs. In Diyarbekir, one day, five priests who had been stripped naked and covered with tar were led through the streets.

The Kaymakam [Nesimi; district governor] of Lice had rejected the verbal order to kill the Armenians, which had been given by a messenger from the Vali, noting that he wished to have the order in writing. He was deposed, called to Diyarbekir and killed on the way there by his escorts.

In Mardin, too, the Mutessarif [mutasarrıf] was dismissed because he did not want to deal with the Armenians according to the will of the Vali. After his dismissal 500, then 300 Armenian and Syriac notables were sent to Diyarbekir. The first 500 did not arrive in Diyarbekir; the other 300 were never heard from again.”

Excerpted and translated from: Lepsius, Johannes: Der Todesgang des Armenischen Volkes; Bericht über das Schicksal des Armenischen Volkes in der Türkei während des Weltkrieges [The Deathmarch of the Armenian People; Report about the fate of the Armenian People in Turkey during the World War. Reprint of the 2nd edition.]. Reprint der 2. Aufl. [Potsdam, 1919], Heidelberg 1980, p. 74-76

The Martyred Bishop

“On the day that these two thousand were sent into exile the Armenian bishop of Diarbekir went with them as far as the city gate, but then, I was told, the Vali ordered him back to the prison, saying, ‘I am going to burn your beard!’ After a few days the bishop was reported to have died of typhus fever! No one believed this report, and when, the next day, I saw the sexton of that Armenian church, he told me, when we were alone together, how he had been called to the prison and given the bishop’s body to take away and bury. The body was hardly recognizable. The teeth had been extracted, the cheeks had been pierced in many places, and the beard had been burned away. Rumor had it that after the bishop had been tortured to the point of death, he had been taken out into the prison yard, saturated with oil, and, in the presence of guards and officers, burned to death. He was a man of unusual outrage and aggressiveness, who, at the beginning of these troubled times, had taken active steps to appeal to Constantinople for pity on his people, and who, even in prison, had continued to make efforts in their behalf. This probably was the reason for the peculiar savagery of the treatment accorded to him.”

Excerpted from: Henry H. Riggs: Days of Tragedy in Armenia: Personal Experiences in Harpoot, 1915-1917. Ann Arbor, MA: Gomidas Institute, 1997, p. 53f.

The Courageous Pastor of Diyarbekir

“But in the midst of all that terror, one man seemed especially inspired of God to lead the thoughts of that hopeless people to the only source of hope and peace. The pastor of the Protestant church seemed to be the only man who was not afraid. He was an old man, long since retired from the ministry, who had consented to take charge of his own church for a few months, and who was, during those days, the pastor of the whole city.

I asked him one day if he was not afraid to go about. He smiled and said: ‘I suppose that it is dangerous, but I would rather go in this way than to stay at home at such a time as this.’ So, from home to home he went, bringing consolation and help, and every evening, in the great Protestant church, he held a service of prayer. Diarbekir is a city of many sects and of bitter feuds among them, and I never hoped to see a union service of prayer where all were together. But there they were, Protestants and Gregorians, Catholics, Jacobites, Chaldeans and all, drawn together by their common anguish and by the inspiring faith of that one man who led their thoughts and prayers at those evening meetings. It was an impressive and pathetic sight to see the throng bowing there in earnest prayer, each one going through the forms to which he was accustomed in his own church, but all united in the spirit of agonizing prayer to God. At the close of each service the pastor led and all joined in that chant of the ancient Armenian church, ‘Der Voghormia’, a chant that all through the ages has voices the despairing faith of that martyr race, ‘Oh Lord have mercy!’”

Excerpted from: Henry H. Riggs: Days of Tragedy in Armenia: Personal Experiences in Harpoot, 1915-1917. Ann Arbor, MA: Gomidas Institute, 1997, p. 54