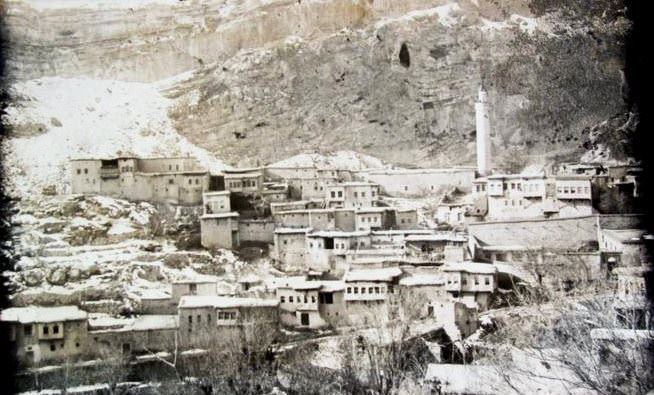

The kaza’s administrative seat is located on the left bank of the river of same name (Chmshkadzak), which is the right tributary of the Aradzan (Trk.: Murat) River, in a mountainous, forested area, at 1,300 m above sea level. The city is built in an amphitheater like concave.

Toponym

The Armenian name of the city and kaza of Chmshkadzag derives from Byzantine general and emperor of Armenian descent, Hovhannes Chmshkik (Հովհաննես Չմշկիկ; Grk: Ἰωάννης ὁ Τζιμισκής – Ioannis I Tsimiskes), who was born here. Before, it was known as Hierapolis, or Hieropolis (‘holy city’).

Administration

It was part of the Tsop’k’ (Sophene) province of Greater Armenia.

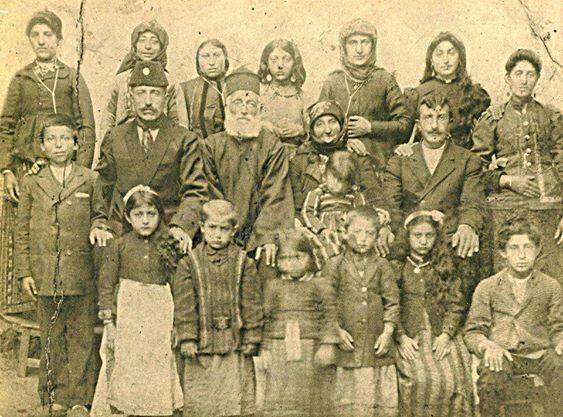

Population

In 1800-1830 Chmshkadzag had about 6,000 inhabitants, of which 4,000 were Armenians, and the rest were Kurds, Turks and others. During 1830 to 1850 the population increased to 8,000, of which about 6,500 were Armenians.

According to the statistics of the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople, 4,494 Armenian lived in 22 localities of the kaza, maintaining 19 churches, two monasteries and 17 schools for 729 children.[1] At the turn of the 20th century there existed two Armenian schools in the town of Chmshkadzag, called Mamikonyan and Partyan, which served about 200 students.

In the 1930s, Çemişgezek’s population was barely 5,000 people, including a small number of Armenians. In 2011, about 3,000 people lived in the city, mostly Kurds and Crypto-Armenians.

Armenian Settlements in the kaza Çemişgezek

Chmshkadzag (administrative seat), Ashgani (Eshkyuni), Arteka (Artekan), Badratil (Petretil), Bazabun (Bazabon), Brady (Prat), Brekhi (Prekhi), Yeretsagrak (Yeritsagrak), Tuma Mezre, Khachtun, Kharasar (Gharasar) Khndrrikik (Khndrik), Karmri, Hazari, Dzndzor (Jindzor), Mamsa, Mankudzak, Miatun ([Arm.: Գեմիջի – Gemiji, Tr. Gemici), Morshkha (Morshkhan), Murnayi, Partizak (Bakhchejik), Poghos (P’oghosi), Setrka, Tisna, Vasakavan, Urtek, Pasha Mezre, Odzgyugh.

History

Until the 15th century the area was quite crowded and well-maintained. However, after the conquest by the Ottomans in 1474, which was accompanied by mass captivity of the inhabitants, for centuries Chmshkadzag turned into a small village.

At the beginning of the 20th century the town’s outer circumference was more than 8 km. It was divided into many small quarters. The Armenians lived mainly in 10 districts of the center, in the adjacent plateau called Yuch-bek. The Armenian prelacy was in the center. Cliffs with very steep slopes rise in front of the city.

The Armenians maintained two churches. The older one, which served as the main church, was dedicated to the Holy Mother of God (Surb Astvatsatsin), and the newer one was called Surb Toros (built in 1825 on the site of a former sanctuary). Various antiquities and historical monuments were preserved in Chmshkadzag: the remains of the defensive wall that once surrounded the city, the traces of the fortress, the ruins of Armenian castles, churches and chapels, and other buildings. The ruins of several houses dating back to the 13th century in the western part of the city, which the locals call ‘jin-viz’, have traditionally been associated with the name of Genghis Khan. No traces of any Roman-Byzantine monument were observed in Chmshkadzag at all. The antiquities and monuments that have survived are almost exclusively Armenian, with the exception the mosques and the state administrative buildings built for different purposes. In Chmshkadzag, on the river of the same name, there were two stone bridges, which stood at the beginning of the 20th century and were in a very good condition.

General and Emperor Ioannis Tsimiskes (Ἰωάννης ὁ Τζιμισκής – Hovhannes Chmshkik; reigned 969-976)

“Hovhannes (John) Chmshkik was one of the most powerful emperors of Byzantium. He came from an Armenian noble family, and was a cousin of Emperor Nikephoros II Phokas (Νικηφόρος Φωκᾶς; c. 912 – 11 December 969). During his reign he was appointed commander of the Eastern troops, and defeated the Arabs in a major battle. But in 969, with the help of Empress Theophanu (Theophano), he killed his uncle, the emperor, and seized the throne. Then he started doing charity, distributed all his property to the poor, built hospitals, where he often visited, bandaging patients on his own. The change of emperor caused panic in the empire. The territories occupied by Nikephoros in the East, such as Cilicia, Phoenicia, etc., were lost, in the north, Kievan Russia was threatening the Greeks, the famine had not stopped for three years.

Ascending the throne, Hovhannes Chmshkik was able to save the country from internal misery. In 971 he defeated the Russian prince Svyatoslav, who invaded Thrace, and annexed the northeastern part of Bulgaria to the empire. He won his first victory over the Arabs in Antioch after a war with Russia in Dorostol (Bulgaria) and a peace treaty. He made two raids to the east, as a result of which he was able to return Syria to Phoenicia. During the wars against the Arab Caliphate, he tried to conquer a number of regions of Bagratuni Armenia, but the Armenian king Ashot III the Merciful moved forward with an army of 80,000, and peace was made between the two monarchs.

According to the sources, the death of Hovhannes Chmshkik was due to poisoning. The emperor’s appearance was described by his contemporary, the Byzantine historian and chronicler Leon Diakonos (Λέων ο Διάκονος – Leo the Deacon):

‘He had a white face, blond hair, wet and blue eyes, a sharp look, a small and thin nose, a reddish beard. He was short, but had a wide back. He had incredible strength, his heroic soul was invincible and it was incomprehensible how he fit into such a small body. He attacked a whole army without fear, defeating the enemy and returning to his army safe and sound. He surprised everyone with his generosity and kindness. Anyone who asked for anything from him was never disappointed. He treated everyone with love and an open heart. If he had not been poisoned, he might have distributed the whole imperial treasury to the poor, but John’s fault was that he drank too much at feasts and indulged in bodily pleasures.’”

Quoted and translated from: https://armday.am/post/119522/hovhannes-chmshkik-bjo-zandiaji-hajazgi-amenahzor-kajsrerits-meky

Destruction

Some Armenians fell victim to massacres, while the remaining population was deported to various destinations.

In the county seat of Çemişgezek, raids for weapons began on 1 May 1915 in the Armenian schools, the stores of the bazaar, and the homes of public servants; a day later, about a hundred people were arrested. The tortures to which they were subjected were said to be more cruel than anywhere else – some men were nailed to the wall – and lasted until 20 June, when the kaymakam, the head of the district, announced that the prisoners would be transferred to Mezreh, the twin capital of the province, to be judged there.

On 1 July 1915, the crier in Çemişgezek announced the deportation order. Already the following day, one thousand Armenians had to leave, after some children and young women had been kidnapped by Turkish families earlier. The convoy took four days to reach Arabkir, and from there moved to Harput three days later. Although this route usually takes only a day and a half, it now required three weeks, because the deportees had to make arbitrary, enormous detours. From Mezreh, they continued on to Diyarbekir via Hanlı Han, where the male deportees between the ages of ten and 15 and 40 to 70 were taken from the convoy and housed in a caravanserai. When the rest of the convoy reached Ergani [Argana] Maden, they saw hundreds of corpses decomposing on the banks of the Euphrates. Six weeks later they reached Siverek, where the deportees from Çemişgezek were robbed and some massacred. In Urfa, the convoy was split in two to continue to Suruc and Rakka, respectively. After passing through the transit camps of Mumbuc and Bab, only 150 women from Çemişgezek reached the Aleppo transit camp.

In the kaza Çemişgezek, the village of Garmrig [Karmrik] was particularly affected, where the search for weapons took place on 19 June 1916. On 3 and 4 July 1915, 200 men from Garmrig and the surrounding villages were arrested and executed on the following days by gendarmes as well as units of the Special Organization; at the same time, all boys under the age of ten were separated from their families. On 5 July, the women of Garmrig were summoned to the church to register their property before deportation to Urfa. On 10 July 1915, the first convoy of women set out from the villages of the Çemişgezek kaza and reached the banks of the Euphrates River in the evening of the same day, where the escorts showed them the blood-stained clothes of their murdered husbands. In Arapgir (Armenian Arabkir) the convoys from Çemişgezek united. “A number of villagers from the kaza, especially those from localities in the north, managed to flee to the Kurdish areas, where they survived as best they could until spring 1916. They moved on to Erzincan when the Russian army took control of the region.”[2]

The First Report? The Plight of Arshaluys Martikian (1901-1994) from Çemişgezek and Memoirs of other Armenian Survivors

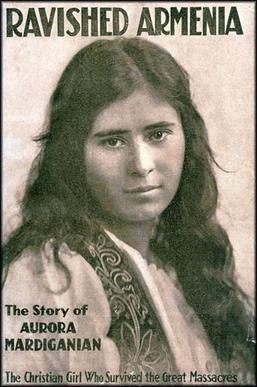

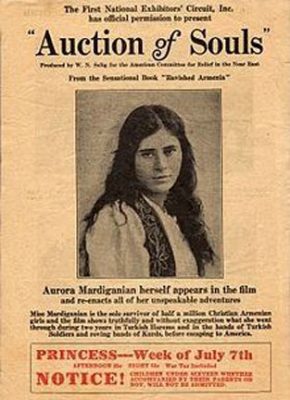

She was born in January 1901 as Arshaluys (also Arshaloys) Martikian (Արշալոյս Մարտիկեան) and is considered the author of the first account of an Armenian genocide survivor to appear in an international lingua franca. Her family name is pronounced Mardigian in the Western Armenian language branch. The given name literally means morning light, that is, daybreak or dawn. The Latin equivalent is Aurora, commonly used in Armenian as Orora.

With a different first and last name, she became known as Aurora Mardiganian in the USA, where she lived from the age of 17, first in New York and later in California. Did her original first name sound too exotic to American or English ears? Did she change it on her own initiative or was she pushed to do so? And if so, by whom? Who changed her birth name from Martikian to Mardiganian? With her marriage, late for Armenian women of that time, Aurora took her husband’s name, Martin Hoveian, in 1929.

Dual Victimization

The fate of Aurora Mardiganian, alias Arshaluys Martikian, points to a dual victimization in which the Western host society participated.

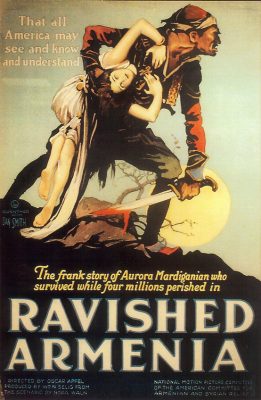

U.S. Armenian literary scholar and poet Peter Balakian, British film historian Anthony Slide, and a number of other publicists have drawn attention to the media as well as commercial exploitation of Aurora Mardiganian.[3] “She had been exploited by people,” Slide said in 2015 at an event commemorating the 100th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide. “She had been exploited by Harvey Gates, who was one of the men behind the book and the film. She was exploited by the filmmakers. She was exploited by Near East Relief in a way because they were using this film to raise money and to their credit, they raised hundreds of millions of dollars for Armenian relief, but they didn’t seem to realize how to treat this young girl. She was just an object, really, to be used.”[4]

The sixteen-year-old refugee girl, who arrives in New York in 1918 and barely speaks English, catches the eye of journalists there through advertisements in which she was searching for the last of her brothers. Soon she is interviewed with the help of interpreters. Then she comes to the attention of Harvey Leyford Gates, at that time a 24-year-old journalist and author of scripts for silent films. H. Gates is touched by Martikian’s story of suffering and at the same time smells a journalistic sensation. Together with his wife, the novelist Eleanor Brown Gates, he persuades the young Armenian’s guardian of the time that she should pursue a film career. Soon the Gates become her legal guardians. But first, H. Gates records Arshaluys’ story as she supposedly conveyed it to

him orally in Armenian and through translations of her Armenian guardians into English. As early as the end of 1918, her biography Ravished Armenia: The Story of Aurora Mardiganian, the

Christian Girl, Who Survived the Great Massacres was published under the author’s name Aurora Mardiganian, shortly followed by the film version, which was released in Great Britain under the title Auction of Souls and was shown in cinemas as early as January 1919. Both the book and, even more so, the silent film became lucrative mass successes; tickets cost ten times the usual price.[5]

“Nothing could be more affecting than this vivid picture of the greatest tragedy

of the world,” Hanford C. Judson praised the film in Moving Picture World. [6] Other critics accused Ravished Armenia of “cheap sensationalism.”[7] By the end of the 1920s, interest had already waned considerably, not only because the silent film era was gradually coming to an end. Diplomatic interventions by the Republic of Turkey ensured that the Ottoman genocide was soon forgotten. Today, only a twenty-minute film remnant of the silent film Ravished Armenia remains.[8]

The filming and commercial exploitation of the tale of woe of Aurora or Arshaluys Martik(an)ian was justified by the fact that it served a good purpose, fundraising. In fact, thanks to this successful promotion, the U.S. Near East Relief organization took in close to $117 million by 1929, instead of the $30 million originally targeted, which is equivalent to $2 billion today.[9]

The teenage protagonist, who came from the deep central Anatolian province, was completely overwhelmed mentally and physically during the filming in Los Angeles and the promotional tours for the film, and eventually she threatened to commit suicide:

“Mardiganian made her way to Los Angeles, unknowing of what she had agreed to. She faced numerous psychological and physical challenges during filming, many of which could have been avoided. ‘The first time I came out of my dressing room,’ she recalled, ‘I saw all the people with the red fezzes and tassels. I got a shock. I thought, they fooled me. I thought they were going to give me to these Turks to finish my life. So I cry very bitterly. And Mrs. Gates says, ‘Honey they are not the Turks. They are taking the part of those barbarians. They are Americans.’ While shooting a scene that required her to jump from roof to roof, she fell and broke her ankle. She was not allowed to rest and heal her injury and was made to continue shooting with bandages in full view. Film historian Anthony Slide remarks: ‘Audiences were presumably expected to believe the bandages covered wounds inflicted by the Turks rather than the barbarians of Hollywood.’

These instances of neglect represent a process of retraumatization, where Mardiganian had to relive the horrifying experiences of the genocide. She was not offered psychiatric care to help her heal. To put this concept in perspective, draw a hypothetical example from the Holocaust. It is highly unlikely to think of a Holocaust survivor acting in their own semi-biographical film a year after they arrived in the United States. The process of healing for a genocide survivor is intense and arduous; having to act out the scenes that haunt one’s memories would complicate it further.”[10]

At the end of the First World War, trauma treatment was in its infancy. Although the term trauma had been known since the 19th century, the psychological and often physical effects of the experience of war and mass violence were at best researched and treated in connection with the trauma of soldiers who had survived the positional and poison gas wars in Europe. Christian girls and women from the Ottoman domains who, like A. Martikian, had been subjected to repeated experiences of violence over a long period of time with complete disenfranchisement, or who had themselves been victims of – mostly sexual – violence, did not receive the attention or even help of European and North American medicine. Post-traumatic stress syndrome, which was first recognized and researched in the context of Shoah survivors and in the context of the Vietnam War, had not yet been diagnosed in those American women who, like Arshaluys Martikian and many others, suffered from panic attacks, flashbacks, numbing, affect paralysis, or other characteristic manifestations. Electroshock therapy, now considered a method of torture, was used to painfully return such women to American ‘normalcy.’

But how could it happen that the Armenian Genocide became more widely known to the world public at the time of the crime than the Holocaust during World War II, and yet disappeared so quickly from public awareness and into oblivion in the United States? The US-Armenian author and journalist Michael Bobelian has given a differentiated answer to this question: As in all genocide-stricken ethnic groups, most Armenian survivors remained silent. They formed a largely leaderless, internationally dispersed society. Many had watched impotently as their relatives were humiliated, tortured and murdered. Also, many survival strategies were not compatible with common notions of human dignity.

Social marginalization formed another reason for the silence of the erstwhile victims: in Europe and the USA, Armenians encountered blatant xenophobia in the 1920s and 1930s. Bobelian mentions a “restrictive real estate alliance” that prevented land from being sold or leased to Armenian immigrants. In reference to their strong presence in California, especially in the Los Angeles area, Armenians were discriminated against as ‘Fresno Niggers’ and ostracized from schools and social centers as undesirables. Discrimination accelerated assimilation and identity denial. [11]

The silence of the genocide survivors, however, had yet another reason: Those who did not want to or could not flee abroad often lived in neighborly proximity to mass murderers and their relatives in their homeland. The fact that their silence, their far-reaching adaptation to Sunni Islamic majorities, nevertheless did not prevent further persecution is vividly demonstrated by the field studies of the Armenian journalist Avedis Hadjian.(12)

Writing the Unspeakable

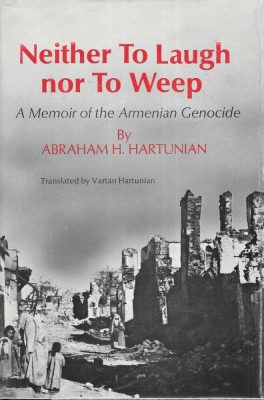

In the sequence of survivors’ accounts translated into the international languages of English and French, Arshaluys Martikian’s memoir Ravished Armenia is probably the closest publication to the event, closely followed by the French translation of Pailadzo Captanian‘s account in Armenian (Paris 1919; English edition: New York, 1922). The Armenian, who came from the Black Sea port of Samsun, hoped to influence the peace negotiations in Paris. It was not until decades later, in 1993, that a German edition appeared.[13] One of the relatively early translations of a survivor’s account into English is Neither to Laugh Nor to Weep (1968) by the Protestant pastor Abraham H. Hartunian, who was born in Severek (Trk.: Siverek) near Urfa.

1919; English edition: New York, 1922). The Armenian, who came from the Black Sea port of Samsun, hoped to influence the peace negotiations in Paris. It was not until decades later, in 1993, that a German edition appeared.[13] One of the relatively early translations of a survivor’s account into English is Neither to Laugh Nor to Weep (1968) by the Protestant pastor Abraham H. Hartunian, who was born in Severek (Trk.: Siverek) near Urfa.

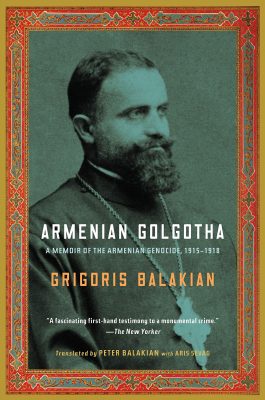

In contrast to Martikian, these reports are from the perspective of adults, similar to the reports of Bishop Grigoris Palagian (Գրիգորիս Պալագեան; Western Armenian: Balakian)[14] and journalist Yervand Otian[15] ( Երուանդ Օտեան or Երվանդ Օտյան; Western Armenian: Yervant Odian), which were translated into English in 2009, i.e. only after a very long time gap. Documentary accuracy was extremely important to these authors. Captanian even initially kept a diary during the deportation, but it was taken away from her by “mountain people.” “My soul, however, is so deeply penetrated by the sufferings endured, my whole self so full of this nightmare, that I have managed to reproduce everything with sufficient accuracy.” [16]

The experienced Constantinople journalist Y. Otian also strove for ‘photographic accuracy’. In retrospect, he wrote: „I was driven as far as Der-Zor, further on, to El-Bousera [Basra], between the Euphrates and the Kopara rivers, the place, where Ezekiel had his vision. I don’t know if I can adequately describe what I saw, but I’ll try.”[17] Otian summarized the result at the end of his report: „So that is the story of my three and a half years of exile. The reader will of course have noticed that I wrote it in the simplest way and in an unliterary style. Before everything else I wanted it to be a truthful story, with no fact distorted, no event exaggerated.“[18]

The narrative of genocide survivors is largely shaped by how old they were at the time of the event. For very young survivors, the focus narrows to the loss of parents and siblings. Since there is no distinct memory of the time before the trauma and thus no standards of comparison, the trauma gains overwhelming importance and perhaps even replaces the pre-genocidal ‘normality’.

The reports and songs of Armenian survivors collected by the Armenian ethnologist Verjiné Svazlian[19] between 1955 and 2010 are of outstanding historiographical importance, because they allow the comparison of the different Ottoman regions and age cohorts. However, the sometimes very late recording, often decades after the events, is problematic here. Especially the memories of survivors who were still very young in 1915 are ‘contaminated’ with the collective historical narrative of later generations. The same applies to other late records in the U.S.[20] and France[21], which also subconsciously reflect the values of the respective host societies. Particularly in the memoirs of Armenians in the USA, it is noticeable that they replaced the belief in fate, which was widespread in the Middle East, with social Darwinist convictions and thus attributed their survival not to chance or fate, but to their personal cleverness. Surviving genocide is thus interpreted as ‘survival of the fittest.’

Autobiographical and even more biographical accounts published by the second or third post-genocidal generation have appeared in incalculable numbers since A. Martikian’s “famous memory narrative”[22]. “Among the memoir literature published in the diaspora by Armenians from Dersim is the well-known autobiography of Hampartzoum Mardiros Chitjian [1901-2002], who was from Peri (Çarsancak; today Akpazar) and recorded detailed memories of his childhood in Dersim in ‘A Hair’s Breadth From Death: The Memoirs of a Survivor of the Armenian Genocide’ (2003).” [23)

Martikian’s narrative is problematic in that it will probably never be possible to determine how much of it is due to Harvey Gates’ editing. What did he add, what did he leave out? What did he misunderstand or distort? The book Ravished Armenia contains a number of inaccurate or oblique factual assertions. The most sensational was the claim in the seventh chapter that crucifixions of 16 Armenian women took place near Malatya, whose corpses Martikian allegedly saw herself. According to Peter Balakian, A. Martikian corrected this already during the filming[24], where this episode was nevertheless used, whereas the real rectification presumably happened only 70 years later in the conversation with Anthony Slide.[25] However, Martikian’s ‘correction’ consists only in the fact that “the Turks” had not crucified Armenian women, but had staked them with crosses. In doing so, she replaced one atrocity with an even stronger, more repulsive one.

Gates introduces in his ‘Prologue’ the good shepherd “Vardabed” who appears in the 13th chapter as deus ex machina to rescue Arshaluys from the harem of Hadji Ghafour. Did Gates know that Vardapet in Armenian is not a proper name but a spiritual title denoting a higher, i.e., celibate and learned, clergyman, an archimandrite? Was the name even deliberately chosen in allusion to the profession of spiritual shepherd? In any case, the fairytale-like procedure of this variant of an “Abduction from the Seraglio” saves more precise and possibly for the protagonist Martikian too unpleasant information about the nature of her rescue. In the 9th chapter, she breaks off the account of her sexual distress in the harem of Hadji (Trk.: Haci) Ghafour with the terse remark: “It is not worth telling more of that terrible night.”

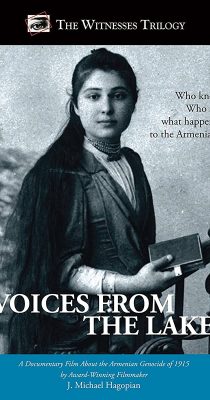

The German edition of A. Martikian’s semi-autobiographical account illustrates in its very title the close connection of physical survival at the expense of individual and collective identity. Throughout her long and painful life, A. Martikian was available for interviews and conversations as a victim and witness, including her compatriot, the documentary filmmaker Dr. J. Michael Hagopian, a native of the city of Harput, who founded the Armenian Film Foundation, whose collection includes 400 videotaped survivor accounts[26] and 18 documentaries[27], including Voices from the Lake (1999) about the genocide in the city and province of Harput. Anthony Slide, who initially thought Arshaluys-Aurora Martik(an)ian was a cinematic artificial character, paid tribute to her after meeting her with these words:

„Andy Warhol promises us all fifteen minutes of fame. For Aurora such altruistic glory lasted somewhat longer — some two years. And then she was forgotten. She died alone, a lost Armenian soul, her mortal reminds unclaimed by either relative or friend (of which she should have had millions in the Armenian community), and she is buried in Los Angeles in an unmarked grave.

Her memory lives on today thanks to various projects that do not benefit Aurora herself. To a large extent, she represents the hundreds of thousands of dead and lost Armenian victims of the Genocide. She also is a victim. She sacrificed herself for a charitable cause and for the profit of others. She survives as a reminder of just how easy it is to be forgotten and tossed aside as the world moves on and forgets the horrors and tragedies of the past.

As a non-Armenian, I am proud that I was able to meet and talk to Aurora about her film, and that I have been able to discuss her work, to reprint the original book, and, for the first time, publish the entire film script in Ravished Armenia and the Story of Aurora Mardiganian (University Press of Mississippi, 2014).”[28]

In honor of Aurora Mardiganian the Aurora Prize was established by 100 LIVES in 2016. The Aurora Prize for Awakening Humanity is a humanitarian award founded on behalf of the survivors of the Ottoman genocide against the Armenians and in gratitude to their saviors. The prize is awarded in Yerevan, Armenia, to an individual whose actions have – at their personal peril – had an exceptional impact on preserving human life and advancing humanitarian causes.

Reappearance of an Armenian Church

“As reported by akunq.net , based on the Turkish Sabah newspaper, when the water level of the Keban Dam, which is located between Dersim and Harput, dropped, the historic Miyadin [Miatun] Church emerged. Alçılı village is located in Çemişgezek [Arm.: Չմշկածակ – Chmshkadzak] district of Dersim province. In the village of Gemici [Arm.: Գեմիջի], where the Keban Dam is located, the Miyadin Church, which is about 300 years old, can be seen. Although the Turkish sources do not give closer information, it is probably an Armenian church.

Local residents, speaking to the newspaper’s journalist, expressed hope that local tourism would be stimulated if the church was renovated.

Villager Fatih Karatepe stressed that the four walls of the church were preserved even under the water. Another local, Çekeria Dilmen, emphasized that according to his grandfather’s accounts, 20 families lived in the village where the church is located.

The church was damaged for years by treasure hunters who removed its stones.”