Toponym

Baghesh or Bitlis (Grk.: βαλαλείςωυ – Balaleisos, Arabic: Badlis), relates to a town in the Aghdznik (Greek: Arzanene) province of Greater Armenia, 18 km southwest of Lake Van, where tributaries of the river of the same name meet. It corresponds to the main fortress of Salnodzor canton of Aghdznik province, which guarded the most accessible natural mountain pass of the Armenian Taurus, the Dzora pass. It was once called Salnodzor after its fortress. At first there was only a fortress in the Baghesh area. Later the city was founded in the territory of the fortress, and the fortress became a citadel.

Armenian Population in the kaza Bitlis

According to the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople, there lived 23,899 Armenians in 57 localities of the kaza, maintaining 57 churches, 8 monasteries, and 15 schools for 979 students.(1)

The City of Bitlis

History

The name Baghesh first appeared in Bishop Sebeos’ ‘History’ (7th century). At the end of the 7th century, the garrisons of the Arab conquerors settled in Baghesh, making it the residence of the Zurarin dynasty, the rulers of Aghdznik. Due to its dominance over the surrounding areas and situated at the junction of trade routes, the merchant Baghesh experienced a rise. The first Arab geographers called Baghesh a prosperous city of Armenia. From the second half of the 9th century, Baghesh was ruled by the Shaybanes, and from the 1st half of the 10th century by the Arab Emirate dynasties of the Kaysiks. In 929–930, the Byzantine general John (Ἰωάννης Κουρκούας – Ioannes Kourkouas) of the Armenian Kourkouas (Gurgen) family invaded Caesarea and captured Baghesh, among other cities. In the second half of the 10th century, after the collapse of the Arab emirates, Islamized Kurdish tribes settled in Baghesh, which had penetrated the southern Armenian provinces as mercenaries of the Arab emirates. At the end of the 10th century, Baghesh was in the hands of the Mrvanian Kurdish dynasty. In the 11 – 19th centuries it was ruled by the Kurds called Ruzaks or Roshkats (Rojaki, Rozagi). Baghesh was the residence of their chiefs. During this period, the Ruzaks lost the power of Baghesh only in 1139-1180 and 1466-1494, for the first time during the rule of the Seljuks, and for the second time during the rule of the Ak-Koyunlus. The Kurdish government of Baghesh became more powerful in the 16-18th centuries. Due to Baghesh’s military position, both the the Ottoman sultans and the Persian shahs sought the alliance of its powerful khans. Attempts by the Ottoman state to destroy the Baghesh Khanate in the 16th and 18th centuries ultimately failed. Turkey was forced to recognize it as a privileged government in Van Elayet. In 1849, the Turkish state, finally suppressing the resistance of the Kurdish Khanate in Baghesh, captured the city, destroyed the fortress and many other structures. Baghesh later became the administrative center of the Ottoman vilayet (province) Bitlis.

Population

At the beginning of the 19th century, the Armenian population of the city of Bitlis counted for 2,200 houses or about 14-15,000 people (out of an overall population of 40,000). According to the statistics of the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople, in 1880 10,724 Armenians (1,532 houses) lived in Bitlis. There were also Armenianized Syriac Orthodox Christians (‘Jacobites’).

Due to inter-ethnic wars, constant violence, heavy taxation, ethnic and religious discrimination, the population of Baghesh, particularly Armenians, has gradually decreased. According to Henry F.B. Lynch, at the end of the 19th century the population of Baghesh was 30,000, one third – Armenians. At the beginning of the 20th century, Armenians had five schools for boys and three schools for girls. More than 100 students attended the well-organized school of Karmrak Church alone.

During the massacres of 1895, about 1,000 Armenians were killed in Bitlis.

The Russian offensive in May 1915 triggered the flight of 80,000 Muslims to Bitlis, according to the German consulate in Erzurum.[2]

In July 1915, the Armenian population of Bitlis was completely annihilated. The massacre was carried out by the Turkish regular army under the direct leadership of the governor of Van, Cevdet. Most of the rescued 300-400 women and children were forcibly converted to Islam. The few survivors took refuge mainly in eastern Armenia.

Until 1915, there were four Armenian churches and four monasteries in the city (according to the four dioceses of the city), each of which had large farms, fields and gardens. On the south-eastern side was the domed Karm(ro)rak S. Nshan church (in ancient times it was called St. Kirakos). This church belonged to the Amlordvi (Amrdovlu) St. Hovhannes Monastery, which played a very important role in the history of Armenian education in the 16-18th centuries; in the 15th century, the Amrdovlu monastery was proclaimed as the center of writing. One of the famous writers was the monk Karapet Baghishetsi from Taghas (born in 1475, d. 1520). Vardan, Arakel, Nerses Baghishetsi, Barsegh Aghbaketsi, Hovhannes Kolot, Grigor Artchishetsi and other theological scholars studied or worked here. Karmrak Church was considered the main church of the city.

Prominent Armenians of Bitlis background

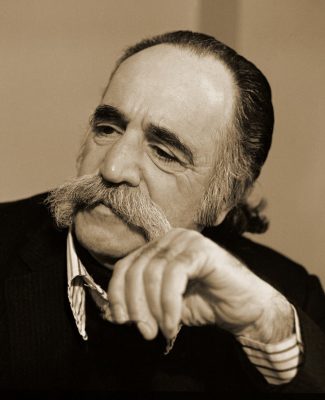

The parents of the US-Armenian writer William Saroyan‘s (1908-1981) came from Baghesh, as did the parents of the Armenian actress Zabel (Mariam Knorozova, 1858-1926). In 1964 Saroyan visited Bitlis and was deeply impressed by the homeland of his ancestors:

“For if I had lived here, I think I would have left it only for a very good reason. This is the most beautiful place I have ever visited, and I have visited many places. (…)

I want Bitlis, I want to live and walk and eat and drink and sleep in Bitlis. Tomorrow will find us on our way to Diyarbekir, or Dikranagert, but I want to stay in Bitlis—apparently forever. I want to die here and be with my dead.”[3]

Destruction

The massacre of Armenians began on 22 June 1915. The last remnants of the Armenians were deported after 1916, when the Russian army and the Armenian volunteer detachments left.

Massacres and Deportations from Bitlis

“In June, a massacre took place in Bitlis. The Armenians of Bitlis and from the villages around Bitlis were deported in the direction of Diyarbekir. The men were beaten to death, 900 women and children were drowned on the way when they reached the Tigris River. During this deportation, the deputy Vramian of Bitlis must have died. The Turkish version was that Armenians wanted to free him, so the gendarmes were forced to kill him”.

Excerpted from: Lepsius, Johannes: Der Todesgang des Armenischen Volkes: Bericht über das Schicksal des Armenischen Volkes in der Türkei während des Weltkrieges. Reprint der Ausgabe Potsdam 1930, Heidelberg 1980, p. 117

“On 22 June, at a time when Bitlis was under serious threat from the Russian troops and the vali and local government were already making plans to leave, panic gripped the city with the arrival of the Kurdish chieftains of Mogdan/Mutki. It was later learned that, shortly before coming to Bitlis, the Kurds had destroyed the 27 Armenian villages in their kaza, massacring the 5,469 villagers where they found them. The same day, the destruction of the Armenians of Bitlis began. The first step was the arrest of Reverend [Khachik] Vartanian, followed a day later by an operation targeting the American mission: it was surrounded by soldiers and gendarmes, who took the handful of Armenian pharmacists, nurses, and teachers employed there into custody. It would appear that the presence of these foreign missionaries was extremely troublesome from the authorities’ point of view. When they proceeded to arrest all the males in Bitlis the same day, Reverend [George] Knapp immediately went to see [governor] Abdülhalik to demand an explanation. Courteous as always, the vali justified the arrests by citing information to the effect that letters from Van had been received by ‘some Armenians’ in the city: ‘the object of arresting all the men was to discover who the recipients [of these letters] were’. These feeble excuses, inspired by the official discourse, could hardly hide the true objective of the systematic round-up, accompanied by unprecedented acts of violence, of all males over ten from the streets, schools, bazaar, and houses of Bitlis – namely, to eliminate all possibility of resistance from the outset. From 22 June on, the men were led out of the city under escort in small groups of between 10 and 15 individuals, depending on the length of rope available to tie them up. They were then shot to death or killed with axes, shovels, or sharp stakes. It took two weeks to liquidate the Armenian male population of Bitlis. In the testimony that Colonel Nusuhi Bey, a witness for the prosecution who had served in the Bitlis region, gave to the court-martial in 1919 about the activities of the commander-in-chief of the Third Army, Mahmud Kamil, he noted in passing that the Armenians of Bitlis were killed ‘in a valley at a half-hour’s distance from the city,’ where ‘they poured oil on them and burned them.’

On 25 June, Cevdet arrived in Bitlis with his 8,000 ‘human butchers.’ (…) Cevdet (…) immediately had Hokhigian and a few other Dashnak leaders in the city tortured. They were subsequently hanged on a nearby promontory, Taghi Klukh. He then turned his attention to the imprisoned Armenian notables, from whom he extorted 5,000 Turkish pounds before demanding the ‘hand’ of the daughters of two of them, Araxi and Armenuhi.

Doubtless in order to bring matters to conclusion as speedily as possible, 700 men were conducted to a spot six miles from the city, slain, and then thrown into pits that they had been made to dig themselves. Not even very young children, it seems, were spared: all the boys from the ages one to ten were taken from their families, led out of the city, thrown into a huge pit, doused with kerosene, and burned alive, ‘in the presence of the vali of Bitlis.’ A different fate was reserved for women, and the children from the city and the surrounding villages who did not fall into this category – some 8,000 people in all. The police began rounding them up on 29/30 June. They were initially left for two days in a few spacious homes in the city or in the courtyard of the cathedral, and then, early in July, conducted by gendarmes and policemen to the southern exit from Bitlis, at the entrance of the Arabi Gorge near the bridge of same name, where they remained for two weeks. The gorge served as a market where anyone who wished to could help himself to the woman, girl or child of his or her choice. At the end of this vast auction, at which 2,000 people found takers, the 6,000 unfortunates who had not were attacked at dawn by Cevdet’s çetes [irregulars]; several hundred perished. The survivors were led in a caravan down the road to Siirt, guarded by gendarmes. The caravan was again harassed by çetes at Dzag Kar. What was left of it trekked past Siirt to Midyat, where approximately 1,000 deportees were murdered, leaving some 30 survivors with the option of continuing their way.

By mid-July, only a dozen Armenian men were left in Bitlis – artisans whom the army considered indispensable – together with the women and girls held by the former parliamentary deputy Sadullah, the mal müdir, the chief of the post office, Hakkı, the proprietor of the hamam [public bath], and others. The authorities also had to hunt down a few children still roaming the streets of the city; they were thrown into the river, or into pits whose sides were so steep that they could not climb back out of them. Finally, Cevdet and Abdülhalik insisted on evicting the handful of women who had found refuge in the American mission, together with the girls at the school. (…) In the end, the girls of the American school escaped with their lives thanks to the chief physician at the Turkish Military Hospital, Mustafa Bey, an Arab who had been educated in France and Germany. Aware that the ‘presence of these girls in the school was a constant thorn in the flesh to the government,’ he nevertheless stubbornly opposed their deportation on the grounds that the hospital was absolutely incapable of operating properly without them: a stand that earned him the enmity of the Turkish officers who were impatiently awaiting their prize. Thanks to Mustafa Bey’s resistance, the matter took a certain importance, so that [governor] Mustafa Abdülhalik was left no choice but to refer the question to Cevdet, who came only occasionally to Bitlis because he had other business to attend to on the plain of Mush. We may thus note in passing that Cevdet, both a military leader and a former vali, outranked Abdülhalik. In any event, Cevdet decided in favor of the army physician.”

Excerpted from: Kévorkian, Raymond: The Armenian Genocide: A Complete History. London, New York: I.B. Tauris, 2011, p. 341f.

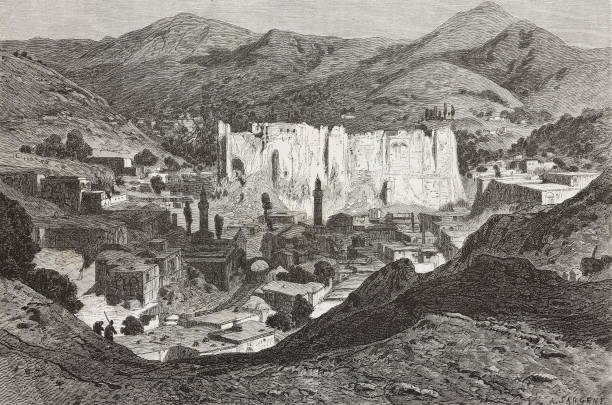

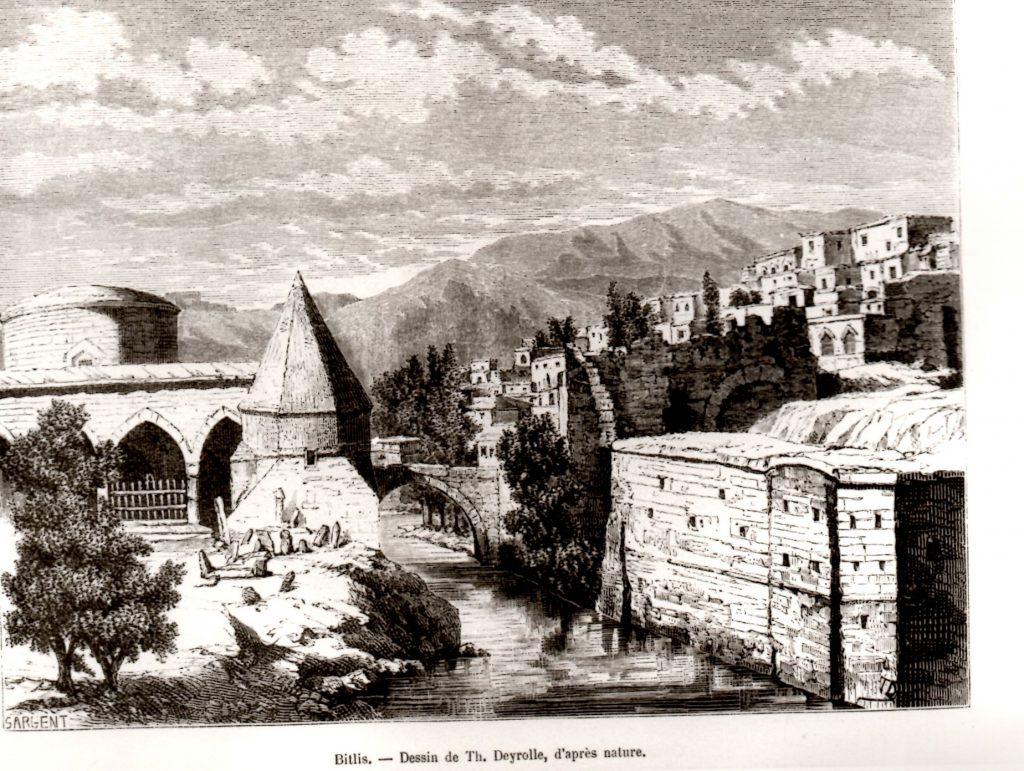

Paul Müller-Simonis: Bitlis City 1888 – “The Capital of Kurdistan”

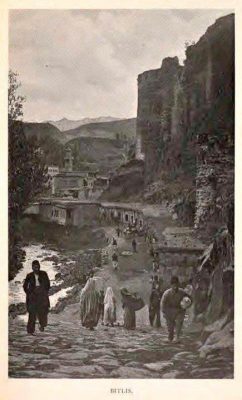

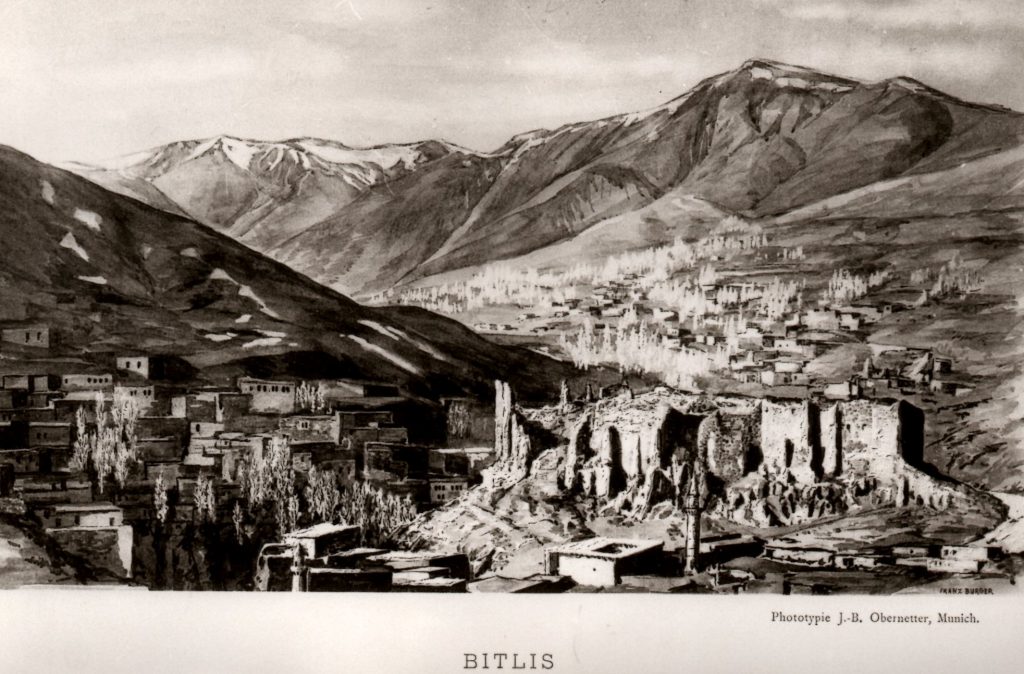

“One would never hope to find a city in these narrow gorges, where the steep and rugged slopes of the mountains completely enclose the bed of the river. But Bitlis is the capital of Kurdistan, and it is therefore quite proper that the city should bear the strange stamp of the adventurers and bandits it harbors.

Arrival 3 o’clock in the afternoon.

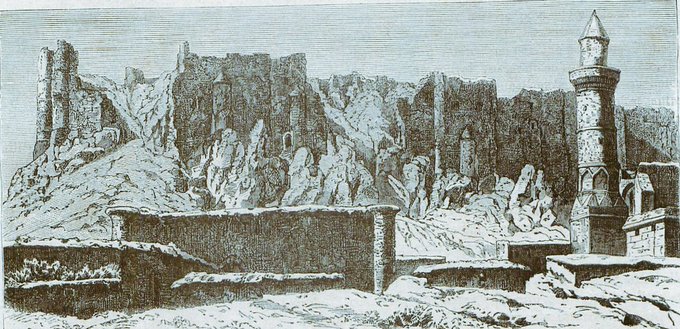

A volcanic rock, a kind of erratic block, closes off the valley; the river flows completely around it, forming a kind of island connected to the rest of the city only by a narrow spit. This rock carries a fortress that is now in ruins. Overlooked on all sides by mountains, this fortress would be poorly able to defend itself against our present-day artillery; but due to the protection on the side of the stream and the steep embankment, it could perhaps have been a significant obstacle to the enemy in the good old days.

(…) The castle is the center of the city. A little upstream, on the right bank of the Bitlis Chaï opens a small valley with gentle slopes. The dwellings are scattered here in gardens; the whole appears as a suburb of Bitlis. The city proper lies around the castle and downstream, all over the slopes, climbing the steep cliffs and offering the eye everywhere breakneck little roads, incredible sights, houses literally built on top of each other.

Since we were still on the right bank of the Bitlis-Chaï, we first had to climb a rocky promontory that dominates the whole city. This promontory bears the old castle of the Kurdish Beys, which today has been transformed into a konak or prefecture. Here also lives the Vali, to whom we first wanted to make a visit and hand over our letters for political reasons, in order to avoid any trouble. (…)

December 2.

We started the day by attending the church service in the small chapel of the Catholic Armenians. (…)

We had breakfast in the tobacco direction; close to it there is an old cemetery, from which one has a magnificent view of Bitlis. Here I also took a photograph of Bitlis, whose location is not only picturesque, but which also receives a very peculiar character from the way the houses are built.

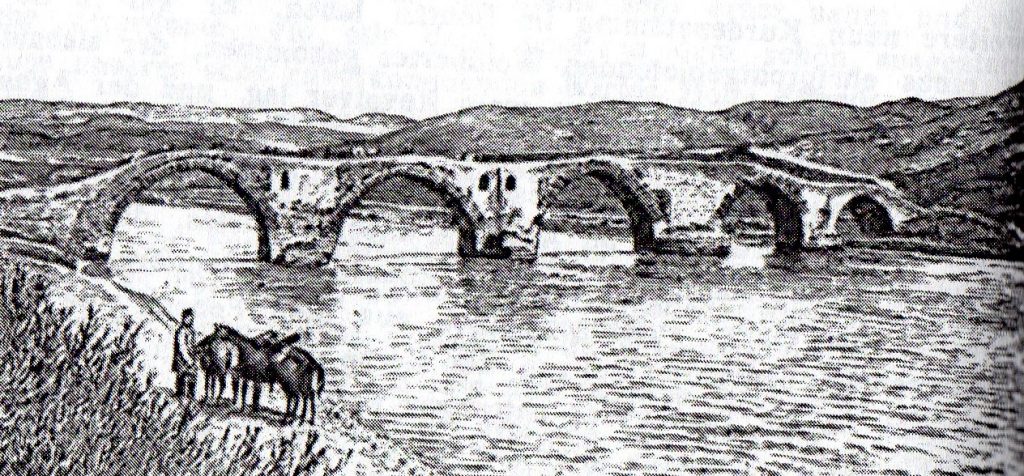

Here there is no more talk of houses made of earth as in Van. The area provides volcanic stone in abundance. This brown-red stone can be worked quite easily the moment it comes out of the stone pit, even with a hand axe, but it becomes hard when exposed to the air. It is used in the construction of all houses, and its regularly hewn blocks give the dwellings a rich and pleasing appearance. The windows, often with pointed arches and opening to the street, are more frequent than in other cities, making the appearance of the streets more lively. Unfortunately, this volcanic stone is a great water lover and makes the dwellings unhealthy due to the absorbed moisture. Also, it does not seem to be very resistant; for in the majority of the arches of the bridges one notices regularly inserted timbers between the layers of stone, which are undoubtedly intended to avoid subsidence. A walk in the lower quarters of the city is extremely pleasant. Numerous bridges of not too solid construction span the river, which is very narrowed by the rocky banks; mills, small mosques, a few Armenian churches enclose it and in this way claim every even spot. And above our heads we also noticed houses, alternating with unbuildable steep rocks or peeping out of a grove and hovering above the abyss in a truly artistic disorder. In such gorges one would hardly expect to find a village, perhaps a pastel as in the Sabine Mountains or in the Abruzzi; but here we have before us in this gorge a real city, highly important for Turkey, since it has about 30,000 inhabitants.

Since in Turkey censuses are based on the number of herds, it is impossible to determine exactly the number of inhabitants. The Kurdish element is predominant here, because from the 6000 houses 5000 are Kurdish and 1000 Armenian, among them also about thirty Catholic families. The Turkish population counts only about twenty households.

The foundation of the city of Bitlis by Alexander does not rest on any secure historical foundation. In the past, however, the fortress was of great importance. The armies of Omar Pasha took the city from the Byzantines in 648, but Bitlis soon became the capital of a Kurdish principality. Its Beys, like many others, took advantage of the decline of the khalifate and secured their independence. Tavernier says in this regard: ‘Bitlis is the capital of a bey or prince of the country, the most powerful and important of all, since it does not recognize either the Grand Sultan or the King of Persia. The Bey or prince who rules in this place, not to mention the inaccessible places, can muster 20-25000 horses and a quantity of infantrymen, composed of the shepherds of the country, who are already ready at the first command.’

Meanwhile, the Bey thought it best to submit to the Porte when Sultan Murad IV had snatched Yerevan and Baghdad from the Persians in 1638. Incidentally, his successors, taking advantage of the sultans’ embarrassments, more or less managed to preserve their independence. Turkey was able to exert a direct influence on Bitlis only by substituting the Valis for the Beys after the hard struggle in Kurdistan that brought about the defeat of Mahmud, the Beys of Van, in 1847. (…)”

Excerpted and translated into English from: Müller-Simonis, Paul: Durch Armenien, Kurdistan und Mesopotamien. Autorisierte Übersetzung aus dem Französischen. Mainz: Verlag von Franz Kirchheim, 1897, pp. 25-229 (https://de.wikisource.org/wiki/Vom_Kaukasus_zum_Persischen_Meerbusen/Bitlis._Sa%C3%AFrd._Der_Bohtan