Toponym

The Armenian place name ‘Vostan’ (‘prince’, ‘aristocrat’) refers to the former dominion of the noble family Rshtuni.

Armenian Population

In the kaza Gevaş 25 Armenian villages with a population of 6,851 existed before the genocide.

Destruction

After the assassination of the Dashnak leader Ishkhan in the village Hirj (205 inhabitants) on 17 April 1915, general massacres were started the following day. In Hirj alone 46 men were killed; at the same time attacks began on the other Armenian villages in the eastern part of the district; the villages Atanan (372 inhabitants) and Spitak Vank (124 inhabitants) were set on fire. In the village of Angshdants (411 inhabitants), Mayor Murad and other notables were shot on 18 April as they attempted to reason with Kurdish chief Lazkin Şakiroğlu.

Island Akhtamar – Ախթամար; Աղթամար

Toponym

The island of Akhtamar (Aght’amar) is the largest of four islands in Lake Van. An Armenian legend, which the ‘poet of all Armenians’, Hovhannes Tumanian (1869-1923) reproduced 1891 in a poem of the same name, explains the place name with an unfortunate, because forbidden love story: Princess Tamar, who lived on the island, loved a young man of low origin, whom she secretly met at night. The young man then swam over from the mainland and orientated himself by the light that Tamar held. However, when Tamar’s father found out about this secret love affair, he destroyed the position light in a rage, and the young man drowned disoriented in the lake. Dying, he breathed the name of his lover: “Akh, Tamar!”

The Turkish version of the toponym, Akdamar, is a corruption of the Armenian Akhtamar, with much more prosaic meaning (‘white vein’).

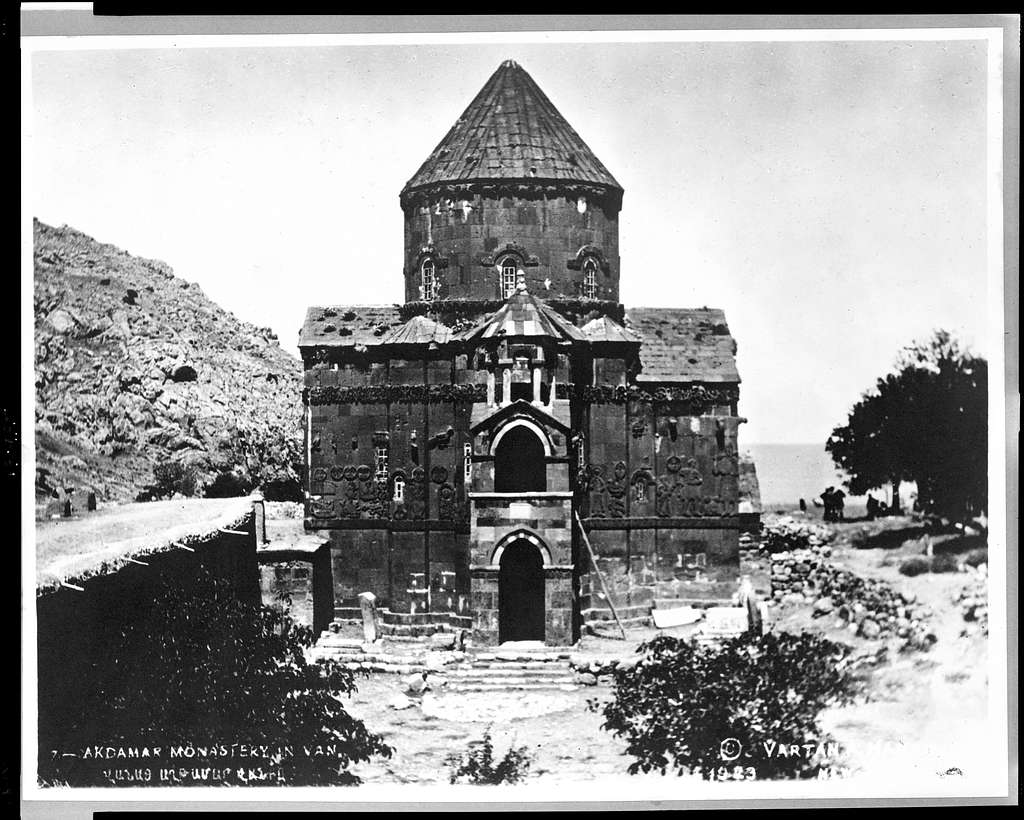

King Gagik I Artsruni, the founder of the royal house of Vaspurakan, had chosen the island of Akhtamar as his residence. “He fortified it, had valuable groves and avenues planted along which the estates of high dignitaries of his court lay. With its stucco ornaments and profane paintings, the palace, which no longer exists, took the Arab palaces as its model.”[1]

The residence cathedral of Surb Nshan (‘Holy Symbol’, i.e. Holy Cross Cathedral; 915-921) was built by architect Manvel on the model of the church in Zoradir and had stones of a recently conquered Arab (Zurarid) citadel near the village Kotom brought from the other end of Lake Van for lack of suitable building material at the southern shore of Lake Van. As a prestigious royal building, Surb Nshan is characterized by its cosmopolitan features. This shows itself with elements and motifs from Iranian (Parthian, Sasanid), and Arab (Abbasid, Umayyad) architecture, as well as in the design of the rich architectural sculpture, e.g. the choice of chimeras (Aries bird, winged fish) or the relatively clumsy physique of the somewhat obese human figures. “The Armenian, or rather Vaspurakanian element expresses itself both through the presence of the martyr saints Hamazasp and Sahak Artsruni, who were tortured to death by the Arabs in 775, and of course also in the composition of the western façade: the appearance of the two seraphim lends it a ‘triumphal’ effect, and within this framework Gagik in his pompous vestments presents his cathedral to Christ.”[2]

The conception of the Christological cycle expresses both early Christianity, with its constant reference to the revelation of divine power (angels as mediators, miracles, Christ’s appearances after his death), and the concept of monophysitism, which emphasized the divine nature of Christ (hence the greater figure of Jesus, his visualization as a hieratic master followed by the disciples, or as God in his glory, and the subordinate role of the Passion). (…)

There was much discussion about the origins of the artists working here. Manuel, the name of the master builder, cannot give any information about his nationality, because it was used in the Armenian as well as in the Greek domain. The works were perhaps carried out by employees of Abbasid workshops in Samarra, Muslims or even Christians, which would explain the choice of Old Testament themes for the sculptures on the exterior.”[3]

Nevertheless, the rich decoration of the outer facades contributed to the cathedral falling victim to the vandalism of local Muslims since the end of the 19th century, because they saw in the figurative motifs devil’s work and a challenge of Islam. With impunity, they shot at the stone sculptures and tore out the turquoise eyes of the figures. The frescoes inside the church were clogged by the missing windows. The Turkish-Kurdish author and human rights activist Yaşar Kemal (1923-2015) boasted that he had prevented the demolition of the cathedral in 1951:

“I was in a ship from Tatvan to Van. I met with a military officer Dr. Cavit Bey on board. I told him, in this city there is a church descended from Armenians. It is a masterpiece. These days, they are demolishing this church. I will take you there tomorrow. This church is a monument of Anatolia. Can you help me to stop the destruction? The next day we went there with the military officer. They have already demolished the small chapel next to the church. The military officer became angry and told the workers, ‘I am ordering you to stop working. I will meet with governor. There will be no movement until I return to the island again.’ The workers immediately stopped the demolition. We arrived at Van city center. I contacted the newspaper Cumhuriyet. They informed the Ministry of Education about the demolition. Two days later, Minister Avni Başman telegraphed the Van governor and ordered to stop the demolition permanently. June 25, 1951, the day when the order came, is the liberation day of the church.”

Source: Kemal, Yaşar; Bosquet, Alain: Yaşar Kemal kendini anlatıyor. Istanbul: Toros Yayinlari, 1993, p. 67

After decades of deliberate neglect, the Turkish Ministry of Culture financed the restoration of the cathedral in 2005-2006, which was not subordinated to the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople, but was reopened on 28 March 2007, as a secular museum under Turkish administration.[4] It was also criticized that no cross could be erected on the dome of the cathedral as the name-giving ‘holy symbol’ and that the monument was not listed under its real name but misleadingly as the ‘Church of Akdamar’. The Armenian journalist and human rights defender Hrant Dink said in view of the controversial restoration work: “The Turkish government is restoring an Armenian church, but is only thinking of how it can turn this to its political advantage.” His Turkish colleague, the Hürriyet columnist Cengiz Çandar, even spoke of a ‘cultural genocide’.

It was not until 2015 that Turkey applied to UNESCO for recognition of the cathedral as a World Heritage Site.

The Catholicate of Vaspurakan

The Catholicate of Vaspurakan existing on the island Akhtamar in Lake Van until the early 20th century was proclaimed in 1113 by Bishop Davit Artsruni in protest against the fact that a minor had been appointed the spiritual head (Catholicos) of the Armenian Church. It was a hereditary office, which only the Artsruni and since the 17th century the Sefedian exercised. As a regional catholicate with dwindling sphere of influence it existed until the death of its last catholicos, Khachatur III (Shiroyan) on 24 December 1895. His predecessor was murdered by Khachatur’s Kurdish servant in 1864. Eleven years later, however, the Ecclestical Council of the Armenian Church declared Khachatur innocent. The merits of his term of office were characterized as follows:

“Thanks to him, the region’s barbarous Kurds, such as Sheikh Jelaleddin, behaved in a mild manner with the unfortunate people of the parishes. Catholicos Khachatour, who was recognized as having administrative skills and a winning personality, began a much-needed programme of reconstruction; restoring buildings, including his residence on the island, the Patriarchate at Akhvank, to which a school was attached, as well schools, orphanages and a museum, where he gathered select manuscripts, some of parchment and with gold encrusted Mesropian letters, found dust-covered in the monasteries and the villages. He collected small and large stelae with cuneiform inscriptions, vessels, etc. It was said that had he had had competent advisors, he would have had more productive period of service.”[5]

After Khachatur’s death and the Hamidian massacres of 1895/6 the office was orphaned and its two dioceses administered by the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople. In 1916, the Ottoman government officially abolished the Catholicate of Vaspurakan.

Narekavank – Նարեկավանք – Yemişlik

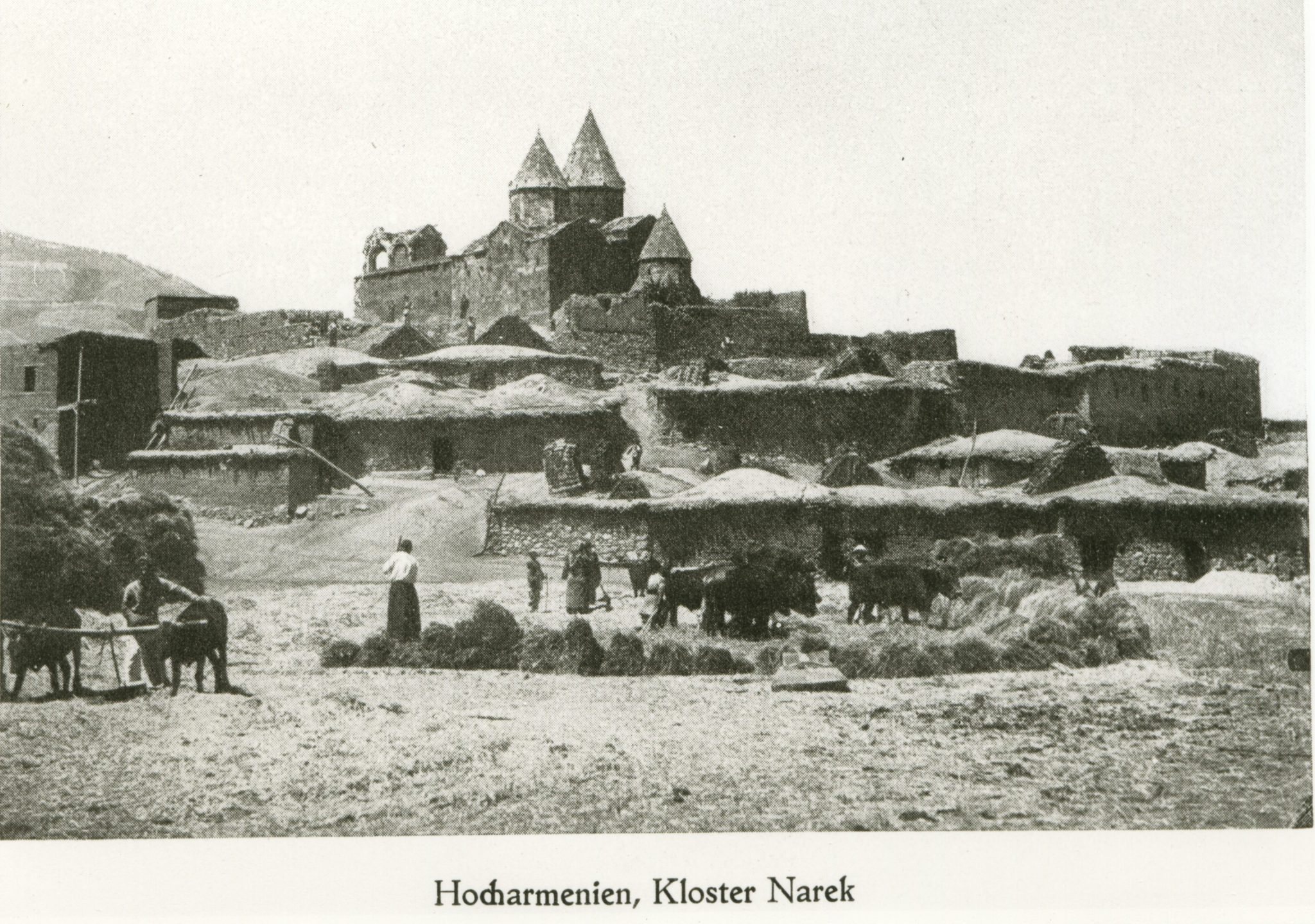

Narek on the southern shore of Lake Van was a village in the ancient Armenian district of Rshtunik in the Vaspurakan region, which came under Ottoman rule in the 16th century. Here the philosopher and theologian Ananias (Anania Narekatsi) founded a monastery in the 10th century with Armenian monks who had fled from the Byzantine dominion to Vaspurakan, which became famous above all by the spiritual poet St. Grigor of Narek (Grigor Narekatsi, c. 945-951; died c. 1003-1011). He was a nephew of Anania Narekatsi and joined the monastery in young age for studies; in 977, he was ordained priest and taught theology at Narekavank until his death. By the time of his death, folklore ascribed miracles to Grigor of Narek, and the cloister became a place of pilgrimage in Vaspurakan. Likewise the historian and later prelate of Sebastia (Sivas) and Urha (Urfa), Ukhtanes of Sebastia (Ukhtanes Sebastatsi; 935-1000), belonged to the well-known scholars of the Narek Monastery. A scriptorium, the first surviving gospel of which dates back to 1069, contributed to Narekavank being one of the most important monasteries in Armenia.

The monastery complex consisted of the churches of St. Sandukht with the mausoleum of Grigor Narekatsi in its eastern part and the domed hall of the Mother of God (Surb Astvadzadzin) to the south. In 1787 Archimandrite (vardapet) Barsegh added a four-pillar narthex (gavit) containing the tombs of Ananias Narekatsi and of the elder brother of Grigor Narekatsis, vardapet Hovhannes. In 1712, after extensive renovation by the archimandrite Minas of Ghapan (Minas Ghapantsi), the monastery underwent a period of upswing in the 18th and 19th centuries. A three-storey bell tower west of the narthex was built in 1812.

In 1884, Aristakes vardapet opened a seminary at the monastery. In 1896, during the government-sanctioned Hamidian massacres, the monastery was attacked by Kurds who killed father Yeghishe and 12 monks. In 1901, an orphanage with up to 30 boys and an integrated school were founded.

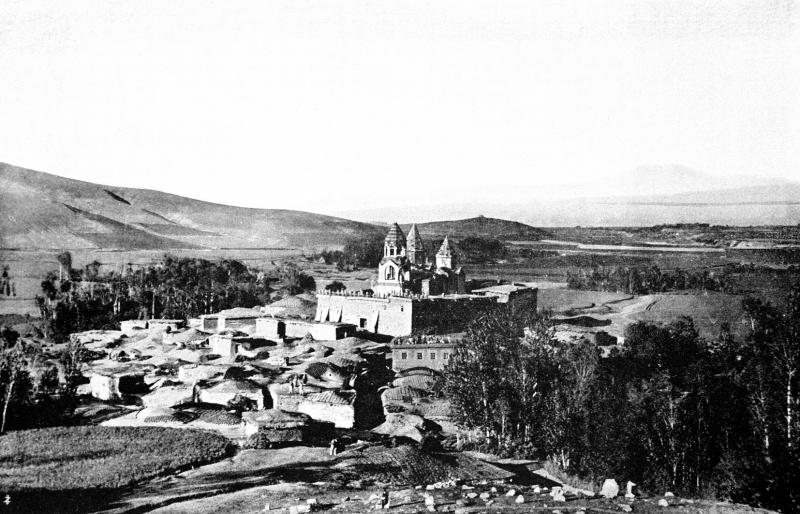

In the early 20th century, residential houses and various buildings surrounded the monastery for economic purposes.

The village and Monastery of Narek were abandoned during the genocide of 1915; when Narekavank was pillaged in 1915, a piece of Christ’s cross – kept there for centuries – was lost forever. According to Sevan Nişanyan the buildings were demolished around 1951, at the same period that an official order for the demolition of the Holy Cross Cathedral of Aghtamar was issued.

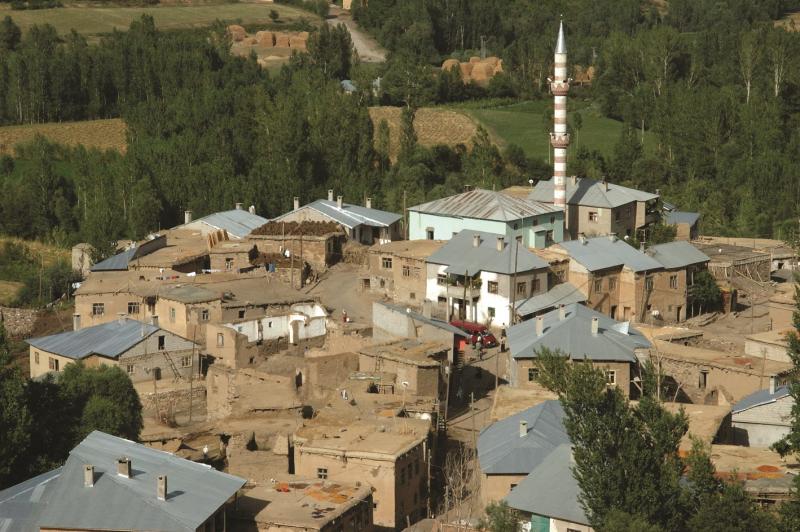

The village of Narek is now largely Kurdish-populated and is known as Yemişlik in Turkish and Nerik in Kurdish. The scholar James R. Russell, who visited the monastery site in 1994, was told by local Kurdish villagers three years later that a 10th century khachkar (cross stone) was destroyed by the Turkish police.

The monastery is completely destroyed. Not a single trace of the complex survived today. A mosque now stands where the monastery once stood. However, almost all homes in Yemişlik are decorated of numerous fragments of Narekavank. Chunks of cross stones, bas-reliefs and Armenian inscriptions are placed into the walls of houses all around.

“Speaking with God from the Bottom of The Heart”: the Book of Lamentations (Matean oġbergowt’ean) by Grigor of Narek

The collection of prayers written in the years 1001 to 1003 forms the main and late work of the mystical poet Grigor of Narek (Grigor Narekatsi). It is so popular that it is simply known as ‘Narek’. It consists of 10,000 lines, divided into 95 chapters called ‘ban’ (‘word’, ‘speech’, ‘matter’), each of which has been subdivided into different paragraphs so that each day of the year corresponds to a prayer. This division is missing in the handwritten tradition and seems to go back to the first editors in the 18th century.

The work belongs – apart from the Bible – to the most widespread books in Armenia and is considered the most important prayer book in the country. It consists of elegiac observations of a soul tormented by the burden of sin, whose development takes place according to a certain logical order: Self-revelation of the praying person, who feels guilty before the divine justice, then complaint about his own misery and instigation of the infinite mercy of God and finally praise of God by the soul filled with new confidence. In this articulation, the gradual upward development typical for the Middle Ages can be seen: the phase of purification is followed by enlightenment and finally by mystical union with God. The central idea of the chain of prayers bases on the antithesis: God is being, man nothing; God is holy, man impure; God is light, man darkness; God is strength, man is weakness. Another antagonism is revealed in the struggle between spirit and matter, soul and body, i.e. between the introverted life of the saint and the extroverted world of the devil.

Written in the first person, the form and concept of Matean oġbergowt’ean were shaped under the end-time expectation of the turn of the millennium and is the confession of a praying soul who strives to God through the world of the senses and through the path of purification, more precisely: the soul of the pious author who intercedes, as it were, for all humanity (Ban 3, Paragraph 2). Biographically, the confession of sins of the poet-ego can probably also be explained by the fact that the author had previously let himself be urged by the Armenian Catholicos to write a diatribe against the religious protest movement of the Tondrakians, condemned as heresy. The work gains universality through Grigor’s inclusion of the whole creation in his prayer, which the poet encourages to praise the eternal and merciful God. Great poetic sensitivity and rich imaginative gift inspired the author to create a mystical-ecstatic work of word art full of personal immediacy.

Little is known about Grigor Narekatsi’s life. He was born in a village on the southern shores of Lake Van. His father Khosrov Andzevatsi became a bishop, but was suspected of pro-Byzantine Chalcedonian beliefs, and was eventually excommunicated by Catholicos Anania Mokatsi for his interpretation of the rank of Catholicos as being equivalent to that of a bishop, based on the works of Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite. Grigor and his elder brother Hovhannes were sent to the monastery of Narek, where he was given religious education by Anania Narekatsi (Ananias of Narek). The latter was his maternal great-uncle and a celebrated scholar who had elevated the status of Narekavank to new heights. Being raised in an intellectual and religious fervor, Grigor was ordained priest in 977 and taught others theology at the monastery school until his death.

Whether Narekatsi led a secluded life, as it is traditionally believed, has become a matter of debate. Armenian philologists Arshag Chobanian and Manuk Abeghian believed he did, while Hrant Tamrazian argued that Narekatsi was very well aware of the secular world and his time, had deep knowledge of both peasants and princes and the complexities of the world. But both views may not be as contradictory as it may seem at first glance.