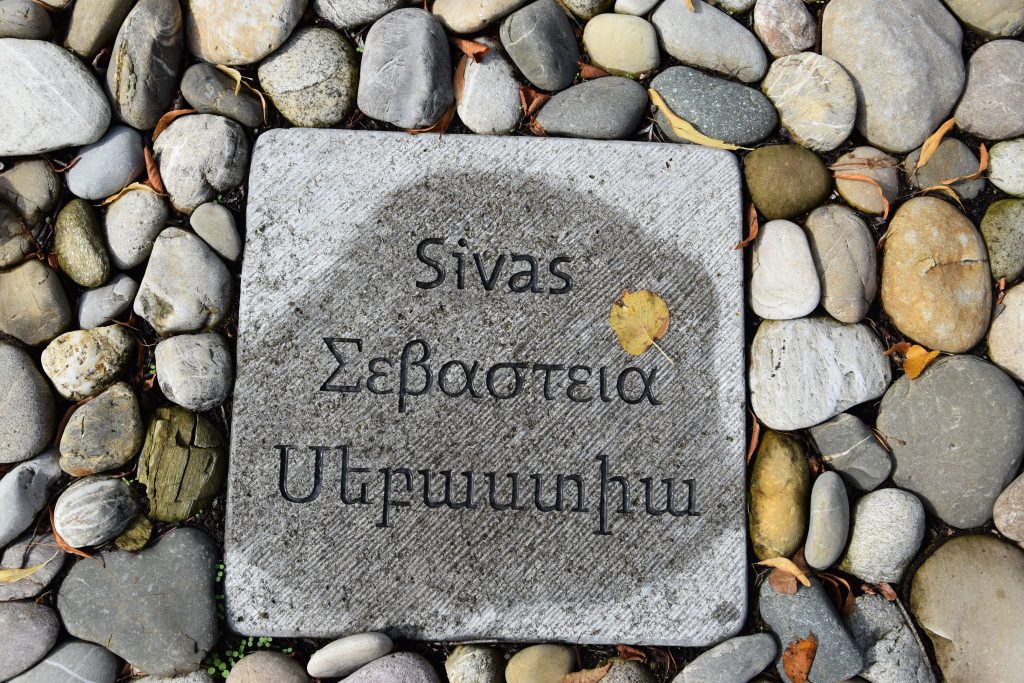

Administration

The sancak of Sivas comprised the eleven kazas of Sivas, Bünyan, Şarkışla (Tonus), Darende, Divriği (Divrik), Aziziye, Kangal, Koçgiri/Zara, Koçhisar, Gürün, and Yenihan.

Armenian Population

In 1914, the Armenian population of the sancak of Sivas alone was 116,817. The Armenians lived in 46 towns and villages.[1]

Armenian Celebrities from the Sebastia sancak

Ukhtanes Sebastatsi (935-1000): prelate; historian

St. Barsegh: Bishop of Sebastia and Asia Minor, canonized in Christian churches

Hovasap Sebastatsi (1510-1564): poet, chronicler

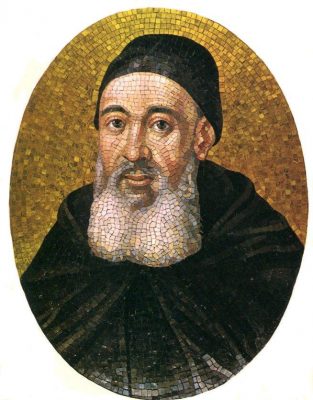

Mkhitar Sebastatsi (1676-1749): Armenian Catholic monk, as well as prominent scholar and theologian who founded the Mekhitarist Congregation, which has been based on San Lazzaro Island near Venice since 1717

Hovhannes Sebastatsi (17??-1830): historian

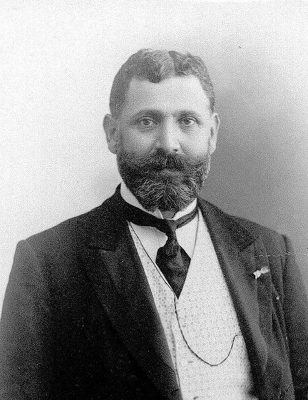

Nazaret Daghavarian or Taghavarian (Նազարէթ Տաղաւարեան,

Turkish Dağavaryan or Çadırcıyan, 1862, Sivas-1915, Karacaören): physician, agronomist, member of the Ottoman Parliament and one of the founders of the Armenian General Benevolent Union (AGBU). He wrote non-fiction books on medicine, history and religion, such as on the Turkish Alevis. He was a victim of the Ottoman genocide.

Vardan Shahbaz (1872-1959): Armenian national hero

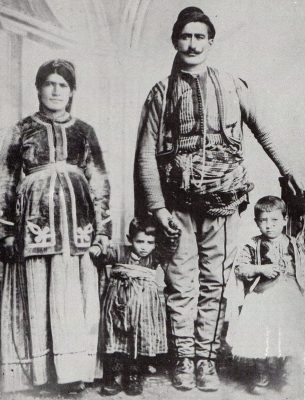

Sebastatsi (Khrimyan) Murat (born 1874, village Govdun, Sivas province – 4 August 1918, Baku): volunteer fighter of the Armenian-liberation movement, Hayduk; national hero of Armenia

Martiros (Mardiros) Harootiun Ananikian (1875-1924): American-Armenian writer, politician, linguist; author in Armenian mythology

Aram Zardarian: Armenian leader of the American labor movement in 1876

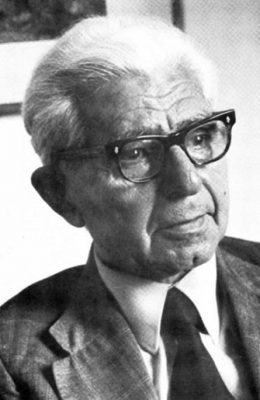

Paruyr Asatur (Asadur; 1882-1964): linguist

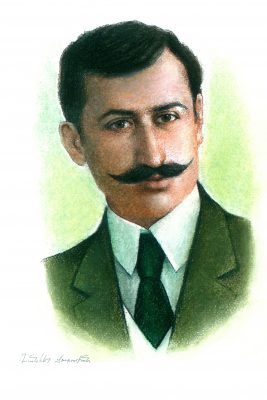

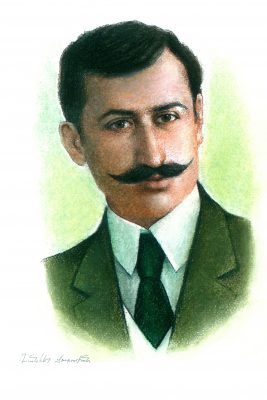

Daniel Varuzhan (1884, Brgnik/Sivas-1915): poet, genocide victim

Trdat Nshanian (1892-1962, Paris): film actor and director

Hrant Glchyan (1896-1959): composer, violinist

Artashes Gmbetyan (1900-1967): actor

Yervand Amatuni (1902-1968): painter

Garegin Adamyan (1908-1980): film director, artist

Maryam Şahinyan (1911, Sivas-1996, Istanbul), photographer

Paul Bedukyan (1912-2001): numismatist, leading master of Armenian numismatics

Torgom Saraydaryan (b. 1917): monk, writer, composer

Aharon Norarian: writer

Vahe Vahyan (born Vahe Abdulian, 1908, Gürün [Gurun; Kyurin] – 1998, Beirut): poet, writer, publicist, public figure

Haroutiun Galentz (born Kharmandaian; also Kalents, Arm.: Հարություն Կալենց; 1910 in Gürün [Gurun; Kyurin] – 1967 in Yerevan): painter

Andranik Tsarukian (Անդրանիկ Ծառուկեան Antranig Dzarougian, born 1913 in Gürün [Gurun, Kyurin] – 1989 in Beirut): poet, educator, journalist

Daniel Varujan: Life and Death

Daniel Varujan (Daniēl Varowžan; Դանիէլ Վարուժան; West Armenian pronunciation Taniel Varujan) was born on 20 April 1884 as the son of a farmer in the village of Brgnik in Sivas Province; his real family name was Chpug(a)qyarian (Č’powgk’yarean; West Armenian pronunciation: Chbukkyarian). His father was falsely accused and imprisoned in Constantinople during the Armenian massacres of 1896. In the same year, his son moved to Constantinople to attend schools of the Armenian Catholic Mkhitarist Order, from 1902 in Venice and from 1905 in Ghent (Belgium), where he studied history, literature, and Belgian and French art until 1908. In 1909 Varujan returned to his native village as a school teacher, and from 1912 he worked as the director of an Armenian school in Constantinople. In 1914, together with Kostan Zorian, Hakop Oshakan, and others, he founded the literary group and eponymous magazine Mehyan (“Մեհեան”).

Varujan was among those arrested on 24 April 1915. Like most Constantinople intellectuals, the Young Turk regime deported him to Çankırı (Kastamonu province), where deportees were initially interned. From Çankırı, Varujan, together with the poet and doctor Ruben Chilingirian, with Onnig Maghazajian and two others, was sent toward Ankara on 19 August 1915, where the small group never arrived, however, because hired Kurdish assassins killed them after a six-hour journey.

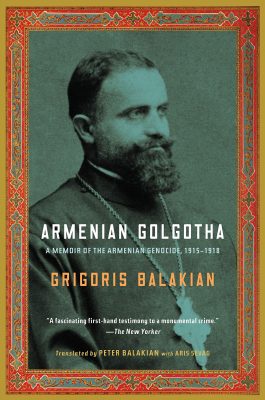

The details of the end of the two poets Varujan and Chilingirian,

who went down in literary history as Ruben Sevak, were described by Bishop Grigoris Palagian (Գրիգորիս Պալագեան; also Palaqian; Western Armenian: Balakian) in his memoirs Armenian Golgotha. Palakian himself was interned in Çankırı, and his recollections contain important, direct information about the fate of his fellow sufferers.

„It was at dawn on that unforgettable black day, Thursday, August 19, 1915, that we, the remaining eighteen Armenian exiles in Çankırı, assembled in front of the two carriages waiting near the bridge by the riverside café. This was the bridge that those traveling from Çankırı to Ankara had to cross, because the causeway stretched from here to Kalecik via Ankara.

We were all very emotional, and despite our best efforts, we were unable to suppress our tears. A deathly shudder enveloped us, tormented our minds and souls, as we witnessed the lamentations of our soon-to-depart Varoujan, Sevag, Onnig Maghazajian, and two [other] friends.

I had never encountered such instinctual emotion. They said to us. ‘Goodbye, we are going off to die. Reverend Father, pray for us.” Varoujan and Sevag turned to us and said: ‘Take care of our orphans.’ And then Varoujan said, ‘I’ve just had a new boy; let the, name him Varoujan.’ Our emotions overflowed, and our minds were in such shock that we could not even offer a few comforting words. (…)

For a long time the members of the Ittihad club[2] in Çankırı had wanted to participate in the jihad and become worthy of the reward of the Prophet of Islam. And so, taking advantage of the transfer to Ankara of Dr. Chilingirian, Varoujan, and the three [other] friends, they had sent a Kurdish criminal named Halo [A] on ahead, with a few of his friends, to a place called Tiuna [Tüney], six hours away., to lie in wait for them.

On Thursday, August 19, when our friends were departing Çankırı, the responsible secretary of the local Ittihad committee, Yunuz, phoned the police guardposts along the Çankırı-Kalecik road to inform them of the departure of our comrades. The next day, Friday, he called the guard office in Tüney, asking, ‘Have those arriving been killed yet?’ But as it was Friday, the police soldiers were having a picnic under a tree a little ways from the guard office, and in the guardhouse there was only an Armenian workman who was busy coating the walls with lime, thus he was privy to these incriminating words.

When the two carriages bearing our five comrades reached the summit in Tüney, where the Kalecik headland begins, the four Kurds waiting in ambush came to meet them. The Kurds advanced toward the first carriage and ordered the driver to halt its horses, to which the police soldier ordered the criminals to leave the horses alone or he would shoot them. But the young policeman from Salonica told the police soldier [whom he outranked] not to resist. He didn’t want the police soldier to know in advance that the crime he had been commissioned to expedite was about to be committed, and by some accidental indiscretion undermine the plan. And so with the compliance of the policeman and the police-soldier, the Kurd Halo ordered those in the carriages to disembark.

Having stepped down, Dr. Chilingirian earnestly pleaded with the four Kurds to spare their lives; he promised that he and his friends would give them all their riches and belongings. But despite these heart-wrenching pleas, the Kurds took our five friends to the edge of a brook that runs through the nearby valley and stripped them, so as not to damage their clothing. Then they drew their daggers and attacked them, ripping their bodies apart and slashing their legs and arms and other sensitive parts. Only Varoujan defended himself, and as a punishment, after gutting him, the criminals dug out the eyes of the patriotic poet.”[3]

Varujan, probably the most important poet of Western Armenian language, left four collections of poems as well as the unfinished cycle The Song of Bread, which could be published only in 1921.

Daniel Varujan: The Aged Crane (Poem)

On the bank of the river, in the row of cranes,

That one drooped its head,

Put its beak under its wing, and with its aged

Dim pupils, awaited

Its last black moment.

When its comrades wished to depart,

It could not join them in their flight.

Scarcely could it open its eyes and watch in the air

The path of the little flock that went along

Calling down to those under the roofs

The tidings, the greetings and the tears

Entrusted to them by the exile.

Ah, the poor bird! In the bleak embrace

Of that cold autumnal silence, it is dying.

It is vain to dream any more

Of a distant spring, of cool currents of air

Under strong and soaring wings,

Or of passing through cool brooks

With naked feet, of dipping its long neck

Amongst the green reeds;

It is vain to dream any more!

The wings of the Armenian crane

Are tired of traveling. It was true

To its heart-depressing calling;

It has transported so many tears!

How many young wives have put among its soft feathers

Their hearts, ardently beating!

How many separated mothers and sons

Have loaded its wings with kisses!

Now, with a tremor on its dying day,

It shakes from its shoulders

The vast sorrow of an exiled race.

The vows committed to it, the hidden sighs

Of a betrothed bride who saw at length

Her last rose wither unkissed;

A mother’s sad blessing;

Loves, desires, longings,

It shakes at last from its shoulders.

And on the misty river-bank

Its weary wings, spread for the last time,

Point straight toward

The Armenian hills, the half-ruined villages.

With the voice of its dying day

It curses immigration,

And falls, in silence, upon the coarse sand of the river bank.

It chooses its grave,

And, thrusting its purple beak

Under a rock, the dwelling-place of a lizard,

Stretching out its curving neck .

Among the songs of the waves,

With a noble tremor it expires!

A serpent there, which had watched that death-agony

Silently for a long time with staring pupils,

Crawls up from the river-bank,

And, to revenge a grudge of olden days,

With an evil and swift spring

Coils around its dead neck.

Source: ArmenianHouse.org http://www.armenianhouse.org/blackwell/armenian-poems/daniel-varoujan.html

Destruction

Approximately 4,000 irregulars (çeteler) were recruited in the Sivas sancak from the Kurdish population of the Darende kaza, from Karapapak (Caucasian immigrants), and freed felons. Half of these ‘gendarmes’ were to go to Sivas, while the others were to be dispatched in the neighboring villages.

“We have information about one of the battalions of çetes created on Muammer’s initiative, the one commanded by Kütükoğlu Hüseyin and Harali Mahir, the murderer of Father Sahag Odabashian. This battalion conducted its operations in the localities of the Kızılırmak valley from 2 April onward. It had been given the mission of arresting the adolescents, village priests, schoolteachers, and notables who had not been conscripted. According to Armenian sources, these operations were accompanied by looting, rapes, and murders, an were followed by the transfer of the men who had been arrested to Zara/Koçhisar or Sivas. Some of these men were killed in the Seyfe gorge or at the level of the Boğaz bridge. The others were interned in the city [Sivas], the medreses of Şifadiye and Gök. We also know that a battalion commanded by Ali Şerif Bey carried outoperations in this valley. The killing of the men of the villages of Khorasan and Aghdk, located on the outskirts of Koçhisar, were its work; the villagers were put to death in the Bunağ Gorge. It is probable that the 4,000 çetes stationed throughout the sancak were given similar missions in other districts during these operations, which took place in April and May. A squadron even took up a position near Sivas, on the banks if the Kızılırmak in a place called Paşa Çayiri, which was converted into a slaughterhouse for prisoners who had been interned in the regional capital.”[4]

“In the same period there was a sharp rise in desertions among the Armenian recruits, who had suffered increasing harassment and persecution. The medreses of Şifadiye and Gök [in Sivas town] were converted into detention centers for Armenians soldiers.”[5]

Around 15 March 1915 17 political leaders and teachers were arrested in Merzifon (Marsovan) and Amasya. On 15 June, twelve people were publicly hanged. “These men were political activists, four deserters from Divrigi [Divrik]/Divriği, and people who had been accused, apparently unjustly, of a murder that had occurred several years earlier. This spectacle took place shortly before the beginning of systematic operations conducted by the police and the gendarmerie that began on Wednesday, 16 June 1915. On that day, 3,000 to 3,500 men were arrested in their place of work or their homes and interned in the central prison or cellars of the medreses of Şifadiye and Gök.”[6]

The first to be deported were the inhabitants of the villages located in the upper part of the Halys/Kızılırmak valley in the kazas of Koçhisar and Koçgiri. “These deportees were put on the road in the latter half of June, before the official publication of the expulsion decree. As elsewhere, first the adolescent and adult men were arrested and killed, after which women and children were set marching southward. By 29 June, the deportation of the villages from the Kızılırmak valley had already been completed.”[7]