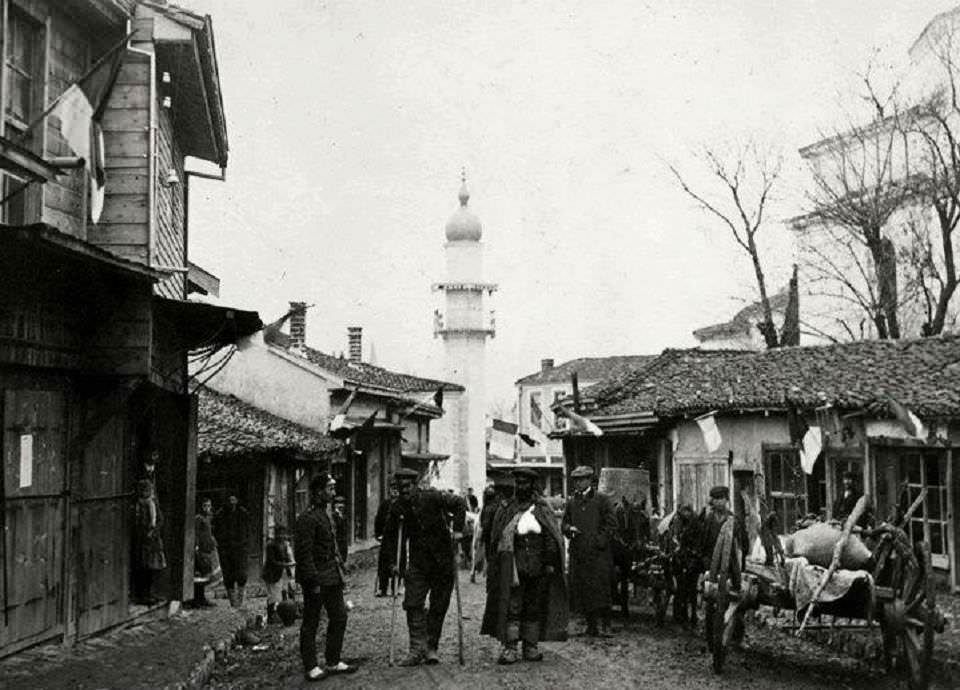

The area in which the sancak’s capital city, Kırk Kilise (since 1924 Kırklareli), lies is bordered on the north by Bulgaria and on the east by the Black Sea. North of Kırklareli there are dense, deciduous forests that are a major source of Turkey’s timber industry. The region south of the city produces wheat, barley, sugar beets, grapes, and tobacco. The area is an important region for viticulture and winemaking. Also south of Kırklareli, on the Edirne-Istanbul route, is Lüleburgaz (ancient Arcadioupolis), site of some noteworthy Ottoman buildings, including a 16th-century mosque built by the architect Sinan.

The large town of Pınarhisar (during WW1 Punarhisar, also Bunarhisar; Grk.: Brysis,) was founded during the reign of Theodosius II, by c. 425, under the name Brysis meaning ‘spring’ in Greek. The town’s fortress was built during the Byzantine era. The town was captured by the Ottomans in 1368 during of a campaign led by Murad I.

Toponym

The Byzantine Greeks called the city Saránta (also: Saranda) Ekklisiés (Σαράντα Εκκλησιές – ‘forty churches’). In the 14th century the Greek toponym was translated to Turkish as ‘Kırk Kilise’. In Bulgarian the city is called Lozengrad.

Population

According to Ottoman statistics of 1910, this East Thracian sancak’s overall population was 159,650; of these, 77,000 were Greeks, 53,000 Turks, 28,500 Bulgarians and 1,150 “others”.[1] Deviating therefrom, the Turkish demographer Kemal Karpat quoted the Ottoman census of 1906-07 for the sancak of Kırk Kilise with 22,022 Muslims, 14,154 Greek Orthodox Christians, 1,599 Bulgarian Orthodox and 780 Jews.[2]

The Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople gave the number of Greek Orthodox Christians in the twelve communities of the Diocese of Kırk Kilise as 25,427.[3]

According to the forcible 1923 population exchange agreement between Greece and Turkey, the Greeks of the city were exchanged for the Muslims (Turks, Pomaks, Karadjaovalides and Albanians) living in Greece.

At present, most of the inhabitants of the city are Turks (Muslims) who formerly lived in Thessaloniki until the First Balkan War of 1912.

History

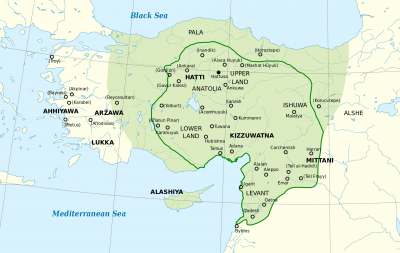

Ongoing archeological excavations in Kırklareli support the claim that the area was the location of one of the first organized settlements on the European continent, with artifacts from the Paleolithic and Neolithic periods.

The settlement and its surrounding areas were conquered by the Persians in 513–512 B.C., during the reign of King Darius I.

In 914 during the Bulgarian invasion in Adrianople led by Simeon I, the settlement was captured by the Bulgarians and was under Bulgarian rule until 1003 when it was lost to the Byzantines. The Ottoman Turks took the city and its region from the Byzantines in 1363, during the reign of Sultan Murad I.

The city was damaged during the Greek War of Independence (1821–1829).

In 1906, the Diocese of Saranta Ekklisies was detached from the Metropolis of Adrianople and was elevated to the status of Metropolis.

In the First Balkan War, the city was captured by the Bulgarian 1st Army in the Battle of Kırklareli on 24 October 1912, but was retaken by Ottoman forces in the Second Balkan War on 21 July 1913. As a result, the Bulgarian and Greek population was expelled or murdered. Some of the expellees settled in Sosopol and other places in the Burgas region. In the aftermath of World War I (1914–1918) Kırklareli belonged temporarily to Greece, resulting in the return of the expellees, but was retaken four years later by the Turks on 10 November 1922. The Treaty of Lausanne (1923) which defines Turkey’s western border in Thrace also defined the western boundaries of the Kırklareli Province.

Destruction

Before and During the First World War

“Diocese of Kirk-Klissi [Kırk Kilise]

This Diocese (…) was the first to feel the evils of Bulgarian Administration so that the whole of the Greek population of the Diocese rejoiced at the news of the approaching re-occupation of Thrace by the Turks. The Greek population even felt relief at the idea of the return of the Turkish Administration. But the deception was a cruel one. Bands composed of the lowest and basest elements of the population invaded the diocese and committed the worst acts of barbarism and cruelty under the very eyes and to the great delight of the chiefs of the Turkish regular troops.

Later on, the Civil Administration itself, when once it had been officially established, acted upon a premediated and clearly set forth programme and started the systematic extermination of the Greek element until the entire Greek communities were driven out.

- KOURDUE.— On the 25th March (o.s.), 1913, some of the inhabitants of this locality were deported to Bulgaria, among whom were the Vicar, George Dionyssiou and his family. On the 27th of the same month armed bands of Turkish irregulars entered the village, and in order to scare the peasants stripped the women of their clothes and raped some of them. The village was terrorized by means of all communication being cut-off for some days with the neighbouring villages. On the 1st of April, George Diogenous, Christos Stylianou, and Nicolaos Christou were murdered by the Turks, between Scopos [Skopos] and Kouroudere [Kurudere]. The same day the village was plundered and the terrified Christian inhabitants took to the mountains, while on the 5th the entire population was obliged to expatriate itself.

KOITROUNDERE, 3. ERVARION.— Following on all sorts of persecution, the inhabitants of both these villages emigrated in April, 1914.

- YANDJICLAR [Yanciklar].— Towards the end of March, owing to the attitude of Turkish emigrants and inhabitants of the neighbouring village, the Greek population was obliged to expatriate itself.

- SCOPOS [Skopos]. — The Turkish re-occupation caused this small town to suffer cruelly. On the 17th of July, 1913, soldiers and Turkish emigrants carried away the cattle, the agricultural produce, furniture and the carriages of the inhabitants. On the 9th of March, 1914, Halvadji, a petty merchant, and George Lampi, were massacred by the Turks close to the village of Kurdere [Kurudere], and on the 13th of the same month, the sub-Governor (mudir) levied heavy contributions on the inhabitants in support of the Turkish fleet; also for the establishment of a telephone, the furnishing of the gendarmerie post, the creation of a municipal garden, and the repairing of the roads. On the 24th of April of the same year, seven of the notables of the town were arrested and thrown into the prison of Adrianople. Their names are Simos Simopoulos, Archimides Iconomidis, Yianacos Illioglous, Euripidis Hadji Anestis, Leonidas Kiradjoglous, Alexandros Tianilis, and Polthronis Skiougenis. On the 21st September a subscription of Ltq. 1,000, in favour of the Red Crescent and the National Defence Committee, was imposed upon the inhabitants.

On the 5th of September, 1915, the town was besieged by the Turkish Gendarmes and 200 other Turks, commanded by the ex-chief of the Gendarmerie of Ismidt [Izmit], Yussuf Bey. No one was allowed to leave the town and orders were given to the inhabitants to make ready for their departure. On the following day, Simos Simopoulos, a teacher, was arrested and carried away by two Turkish emigrants, belonging to Scopo [Skopos] , who killed him on the road to Yenna, at a distance of a quarter of an hour from the town. This assassination was followed by that of Pope Kyriacos Constantopoulos, who was thrown into an unhealthy dungeon, left to languish in it for five whole days and nights, without food or water, while subjected to unheard of tortures.

For five long days the Turkish functionaries, together with the population, gave themselves up to a veritable orgy of cruelty against the Greeks, whom they further stripped of Ltq. 3, 000. On the 10th September of the same year the deportation of the inhabitants began. Aristodhimos Constantopoulos (teacher), Zaphirios Zaphiriades (apothecary), Theodoros Cokalas (merchant), Pelopidas Vavazanides (teacher), and Pope Kyriacos [Kyriakos Konstantopoulos] , were arrested and shared the same fate as that of unfortunate Simopoulos with the only difference that they were buried alive, after being forced to dig themselves their own graves.

- SKEPASTOS.— At the beginning of the year 1914, the Turks set to work systematically to share the Christian population of this locality. Flogging, theft and plunder were in the order of the day. In March, 1914, about five hundred Macedonian Turks surrounded the town and demanded the immediate deportation of its inhabitants.

On September, 1914, the sub-Governor (mudir), Sarakin Tahsim Bey, forced the peasants to hand over to him 40,000 okes of corn, which he had distributed among the Turkish immigrants at Viza [Pınarhisar; during WK1 Punarhisar; Ancient Grk. Βρύσις – Brysis; Vize, Bizye]. Between the period of the re-occupation and deportation of the inhabitants no less than fourteen of its numbers were savagely done to death in the fields, and Dimitri S. Loghothetis met with his death at Viza, the seat of the sub-Governor of Viza. In September, 1915, the inhabitants, after being stripped of all they possessed, were ex- patriated, and after a four days’ march reached Heraclea, whence the majority crossed over to the Asiatic coast in boats, and settled down in Balli Kesser [Balıkesir], and Ada Bazar [Adapazarı].

7. SKOPELOS. — Here also the Greeks had been exposed, ever since the re-occupation of the village to the same dangers and persecutions from the Turkish emigrants as elsewhere; the same misfortunes now befell them and they were expelled finally in 1915.

8. PETRA. — A repetition of the same methods was carried out here. In 1914, Turkish emigrants surrounded the village, and by putting pressure on its inhabitants forced them to leave. In April, the staff of the Agricultural Bank seized the cattle of all the peasants and in September, 1915, the inhabitants were dispersed.

The communities that escaped deportation nevertheless suffered from all the kinds of persecution and unprecedented tyranny at the hands of the Moslem Albanian, Haidar Bey, Governor of Kirk-Klisse, and those under him.

The terrorism exercised on the Greek Communities was systematic and incessant so that their escape from total deportation was little short of a miracle.

A perfect reign of terror was inaugurated at Kirk-Klisse during the retreat of the Bulgarians and the return of the Turks, the former threatening the inhabitants with a wholesale massacre, while the latter plundered and pillaged them. On the return of the Moslem refugees who found that their dwellings had been destroyed by the Bulgarians, they promptly appropriated those belonging to the Greeks, under the indifferent eyes of the Local Authorities.

During the European War the town of Kirk-Klisse was made an important objective by the young Turks, which they attempted by a thousand ways to destroy.

On the 18th of March, 1914, S50 Turkish refugee families established themselves in Yenna, and started to oppress the Christian population. On the 4th of April of the same year officials claimed payment within twenty-four hours of all debts towards the Government. The collectors of the Agricultural Bank exacted the payment of Ltq. 1,700, out of which Ltq.800 were due by the Bulgarian emigrants. The Chapel of the ‘Life-giving Fountain’ (Zoodhohos Pigi) was desecrated. Constantine Michail was deported with his family and further murders committed.

In general, this borough was particularly terrorized. Manifestoes with the heading “The President of the Committee” were thrown into the houses. One of these read as follows : “Either you leave this place, or we massacre you all. By the end of the week none of you must be found here. If on our return we find you here, it will be at your peril. You must understand this.” These manifestoes bore the mark of the Crescent, with the inscription : ‘Padishahim chok yasha’ (Long live the sultan).

- BOUNAR HISSAR. [Pınarhisar; during WK1 Punarhisar; Ancient Grk. Βρύσις – Brysis]— On the 1st April, 1910, all the cattle were stolen by Albanian Turks. On the 11th of the same month, the Christian inhabitants were beaten and otherwise maltreated by order of the sub-Governor (mudir), under the charge of having refused to accommodate Turkish emigrants.

The inhabitants of the Community of Kara-Halil, after enduring savage attacks on the part of the Turks of the vicinity were obliged to quit their abodes and scatter about in Kirk-Klisse. It was under the most perilous conditions that they managed later on to return to their homes.”

Excerpted from: Ecumenical Patriarchate: Persecution of the Greeks in Turkey, 1914-1918. Constantinople [London, Printed by the Hesperia Press], 1919, pp. 9-12

“We shall not let you live here; we shall kill you…”: 1919-1920

“This diocese was terrorized by a secret organization for the purpose of annihilating the Greek element especially that of the open country. Security of life and property within and outside Kirk-Kilisse there was none for the Greeks. The nationalist animosity of the Turkish element for the Greeks often manifested itself in a ferocious manner, while a systematic robbing and compulsory contributions were the least, that the Greeks had to suffer.

A pretty large sum of money was forcibly taken from Karkatchans living in the neighborhood of Kirk-Kilissé and from 12 inhabitants of Petra. Five Greeks returning from Bulgaria fell into an ambush near the Turkish village of Ezekler and were mortally wounded.

In April 1919 Const. Ap. Voutzas was badly beaten in the very town of Kirk-Kilissé. At Skopo [Skopos] the situation of Christians was growing worse and worse on account of the appearance of Turkish bands, which terrorized them to such a degree, that the poor people could not move from their houses.

A band of 15 members under Capt. Zakeria terrorized the district of Skopos, Skepastos, Petra and Skopelo. On Oct. 11 1919 George and Paul Papastathi were robbed outside Skopos. On Oct. 15 two gendarmes under Hassan Tchaoush [Çavuş – ‘sergeant’] arrested all they found in a coffee-shop and carried Kyriako bleeding to jail. In spite of all this the Turkish authorities forced the community of Skopos to sign a document expressing their thanks to the central government.

On Nov. 20 at 10 o’clock p.m. a band of 15 entered the flour-mill of Ch. Skoulidis, took the inmates, beat them, locked them up in one of the rooms, and then proceeded to the plundering of the mill. They carried the spoils to the Turkish village of Keremedin.

On Jan. 15 1920 seven sportsmen, five Greeks and two Turks, were met by a numerous band, which robbed the Christians sparing their lives only for the sake of their Turkish friends. The robberies and violations were intensified in the districts of Xenna [Yenna? Genna?], Skopos, Skepasto and Petra during the insurrection of Jafer Tayar, and under the support of the Thracian Committee. On April 20 1919 while the notable of Kirk-Kilissé, John Pavlakides, was walking in the market place, he was approached by the fanatical Turk Salih Effendi, warden of the prisons und the Young Turkish regime and their inmate under the reign of Hamid, and was threatened with severe punishment for wearing a hat. Salih said: ‘Your name and the names of those like you have been taken note of; we shall not let you live here; we shall kill you; you are ghiavours; I shall destroy your house with a bomb and after annihilating your family I shall run away to Bulgaria.’ He went on threatening and insulting everybody, either Greek or Turk, daring to approach him.

On May 1919 George Karaghiozoglou and Dem. Loulebourghazli were first robbed and then murdered.

On Aug. 20 Dem. Michael of Samakov and George Adamandiou of Skepastos left Kirk-Kilissé in the morning and spent the night in the Turkish village if Kizilgik Deré. At daybreak they started for home. The band, however, which was pursuing them fell upon them, killed the former by shooting him with a mauzer rifle, felled the latter with an axe, and chopped to pieces both of them.

On December 3 Yannakis Papadopoulos of Eukasion was shot dead while on his way to Kirk-Kilissé.

On Dec 13, Turks killed the notable and mouhtar of the village of Kouyoun Dere [Kuyundere], Ap. Mihaloglou. The body bore the signs of several knife wounds.

In the morning of Jan. 11 Ath. K. Katchavounis was found dead in the room next to his grocery bearing the marks of 40 axe wounds.

On May 15 Anast. Mavringos and Angh. Sterghiou of Skopos were attacked by Turks; the former took to his heels and was thus saved; the latter, wounded in the stomach, fell on the ground and was at once finished with a knife.”

Excerpted from: Ecumenical Patriarchate: The black book of the sufferings of the Greek people in Turkey from the armistice to the end of 1920. Constantinople, 1920, pp. 167-170

Skopos, “Pearl of Thrace” (Trk.: Üsküp)

Skopos is an ancient settlement, and the Turkish name of the town – Üsküp – may refer to Scythians (Trk.: İskit), but more likely is a Turkish bastardization of the Greek toponym Skopos (not to be confused with the capital of North Makedonia, Skopje, which is also called Üsküp in Turkish).

The memoirs of the Greek genocide survivor Anastasios K. Valioulis (1881-1953) form a depressing and at the same time highly significant reading, because they were written close to the event. They contain not only the largely chronological account of events, written in prose and verse, of the then teacher, church secretary, and secretary of the Municipality of Skopos, but also contemporary documents (correspondence and appeals).

Skopos was an East Thracian town with “originally about 1,500 homes and 8,000 Greek residents” before the year 1897, according to A.K. Valioulis. By 1914 the Greek population had already decreased to 1,200 families or 5,500 residents, all of whom were deported in 1915. After a five-day passage, the inhabitants were scattered over various Eastern Thracian towns and villages. Only the military situation in the war year 1915 saved them from being deported to the Ottoman interior, to Asia Minor, like other Eastern Thracians. Their apartments and houses in Skopos were occupied or demolished by Muslim fugitives from Serbia and Macedonia. Only after four years, in 1918, could the Greek population of Skopos return; but with just 500 families, the returnees were less than half of Skopos’ pre-war population.

Reconstruction after the Ottoman armistice of Mudros (October 30, 1918) proved extraordinarily arduous and tragically futile: although Eastern Thrace was under the control of Hellenic forces from July 1920, these withdrew just two years later, when Greece had to cede Eastern Thrace again, this time permanently, to Turkey. A genuine protection in Eastern Thrace was not guaranteed even during the short Greek intermezzo there, as among other things the brutal slaughter of five wainwrights from Skopos illustrates.

The memoirs of A.K. Valioulis are not only a poignant document of destruction, but also of human resilience and survival.

The Exodus

“At exactly 12:00 on Thursday September 10 (of the old calendar) 1915, the order to commence was given. In just one hour six hundred and thirty carts left Skopos making their way south. It is impossible to describe the chaos and confusion during this exodus from Skopos. (…)

Now mothers were losing their children, children their mothers. A mass of people running, silently, in a frenzy, scared, the hallowed soil of their fatherland was raining tears, here where the loveliest dreams of their liberation from the Turkish yoke were born, nurtured, lived, and shaped. But alas! Now they were beating the winding path to Golgotha, without hope of resurrection. In the eventide of that day the sky was covered in black clouds that seemed replete with sadness, ready to release gall rather than rain. All around nature stood silent and sad and with a singular tension in the air watched the bloody tragedy unfold —the expulsion of the most quintessentially Greek town of Skopos.

This moment of the baneful exodus for the Skopinos is nigh on impossible to describe, since our heart is squeezed and tears flood our eyes. A massive wave of people, a veritable sea of souls, inundates the edge of Skopos and flows out, moves, runs, proceeds towards the Black Lake. People of all ages, wagons, and Turkish gendarmes form a motley mass, rolling and crawling on countless legs. At this precise moment, the Turks ring the bells of our church to taunt us, our religion and our God, Who, as they said, had abandoned us and the place where we stood at that hour. (…)

14. The confinement of four Skopinos

As soon as the pealing of the bells was heard, our hearts split asunder and all of us began watering the earth of our fatherland with black, hot tears for, perhaps, the last time. And while we, the population of Skopos, were moving away, slogging along the dark and unknown road of exile, disaster and death, the Turks were breaking down the locked doors of our homes and entering to grab whatever we had left behind. Our hearts were bleeding, our pain overflowed, and our agony was peaking. Suddenly the Turkish gendarmes arraigned and held four of our finest citizens, who once they had been prized from the embraces of their spouses and children, were led to the prison next to the martyr Papakyriakos [Pope Kyriakos Konstantopoulos] . Those arrested were:

- Aristodimos K. Konstantonopoulos, former school headmaster

- Pelopidas D. Vavatzanidis, teacher

- Zafeirios F. Zafeiriadis, pharmacist

- Theodoros Kokkalas, merchant (…)

Oh, my! And what a splitting up that was! How cruelly they tore them away from the embrace of their families! Lamentably none of us dare to attack the Turks and the wrongly arrested men are violently separated, while we with bowed heads have to go where our executioners lead us like lambs to the slaughter. And so we leave… (…)

We are leaving. The crowd runs around without any notion as to where it is going. Some people raise their children onto their shoulders and run wherever the flood of people takes them. For a second the sun shines on Skopos but then hastens to hide itself amongst the crimson clouds, so as not to see the orgy of destruction inflicted on the soil of Christian Europe in the twentieth century. (…)

16. Genna, Vrysi, Ahmet Bey

My God! How quickly we move away from our familiar places towards the unknown! How we separate ourselves from the lands of our forefathers! My God! Give us the patience and fortitude to stand up to and suffer our torture! We reach Vrysi (then Bunarhisar; today Pınarhisar), where the Greek denizens there come out to see us and comfort us, bringing with them victuals and gifts for us. But the Turks who hold our lives in their hands at this moment, stop our Greek brothers from approaching us and order us to circumvent the town by heading south through the cabbage gardens, whereby the people of the Mayoralty come, collecting two groats from each coach as toll fare. Genna and Vrysi both have plentiful supplies of spring water. It is said that Xerxes, while on his campaign against Greece (480 B.C.), set up camp here to rest and counted the number of soldiers he had in his massive army. We carried on and reached the Turkish village of Kazankioi [Kazanköy], beyond which we camped in the attractive valley to calm down on the night of Friday 11th September 1915. The following day, Saturday, September 12, we passed through the attractive and beautiful valley of the village of Ahmet Bey and right at midday we arrived at the village itself. This village is populated by Turkish refugees from Serbian Makedonia. They cover themselves with animal skins and do not differ in appearance from bears.

The once lovely and thriving village, the wealthy and clean Ahmet Bey, now seems like the source of all ugliness and filth, a veritable Augean Stables. Without wanting to, I wonder: what has become of its brave and patriotic residents. Alas! They were expelled and sent to Greece by the Turks in April 1914. I served as a teacher in Ahmet Bey, and knew all its residents, and now I recognize all the houses where they once lived! For a second, I believe that the Greek residents will appear and welcome me. The church, the school, and the bell tower, which once I had worked greatly for, lie in ruins, only just about managing to stand upright. The clean, neat and happy houses have been transformed into dunghills! Oh God, what do I see? (…)

Excerpted by courtesy of the editors from: Valioulis, Anastasios K.: Uprooting of Greeks from their Homeland in Eastern Thrace by the Turks; A Survivor’s Account. Ed. E.S. Savas, Aristotelis Naniopoulos, Vasileios Sakellaridis. Translated from Greek by David Anderson. (To be released)