On the eve of the First World War, there lived 25,399 Armenians (including Catholics and Protestants) in 12 localities in the canton (kaza) of Izmit, out of a total population of 70,000.[1]

Eleven Armenian villages were situated within a radius of 15 to 20 kilometers, maintaining close relations with the town of Izmit (Nicomedia).

Aslanbey (Arslanbey) near Izmit, solely Armenian settlement with approx. 3,000 inhabitants; most of them employed at the Imperial Cloth and Fez Factory in Izmit. It has been “supposedly evacuated completely” as noted by the German Consul General Mordtmann on 4 August 1915.[1]

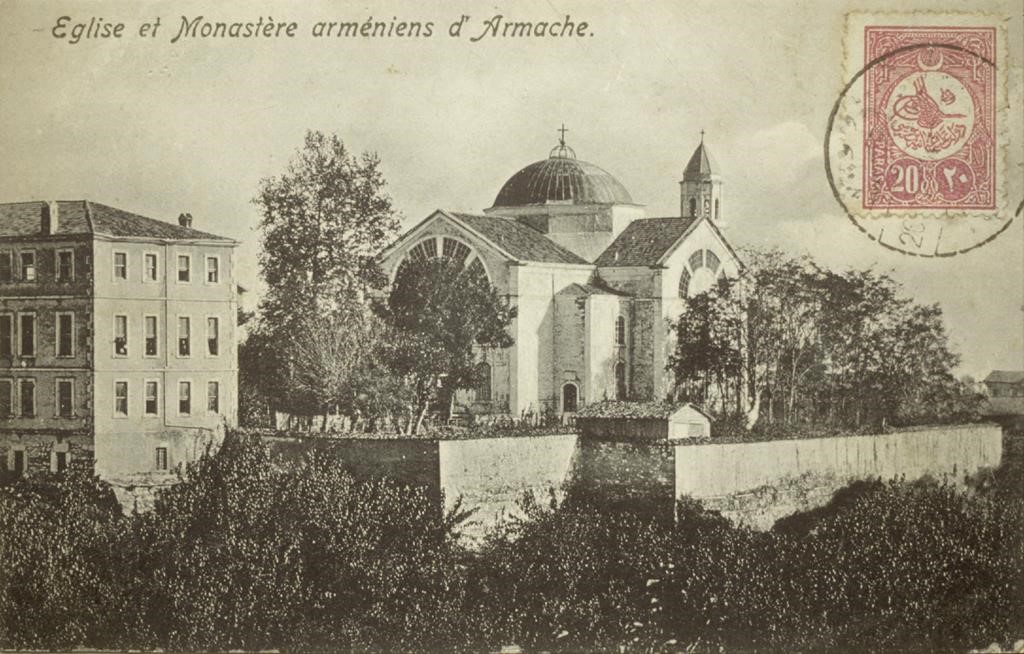

Armash, some 30 km north-east of Izmit, solely inhabited by Armenians (approx. 2,000 people); seat of a large seminary of priests of the Armenian Apostolic Patriarchate, “with rich endowments and a famous old holy relic, was evacuated on the 1st inst.”[2]

[1] Political Archives of the German Foreign Office (PA/AA) https://www.armenocide.net/armenocide/armgende.nsf/$$AllDocs-en/1915-08-04-DE-002?OpenDocument)

[2] Ibid.

Izmit (Nikomedia) City

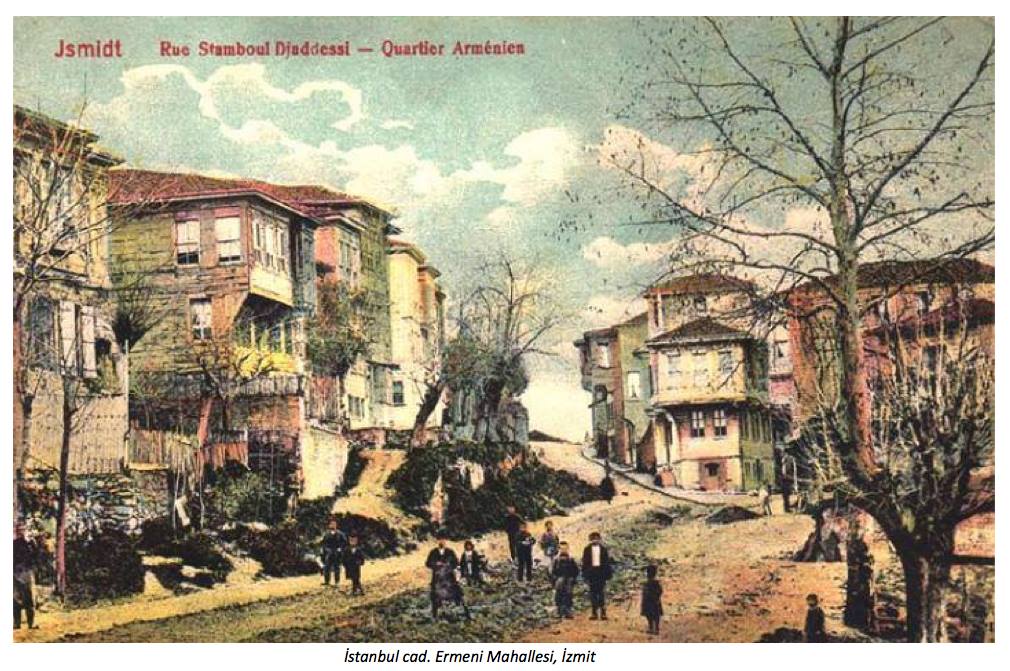

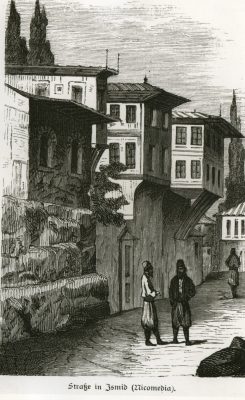

The city of Izmit in the eighteenth century had twenty-three city quarters, of which three were inhabited by Christians and one by Jews. With the construction of a railroad linking Izmit to Haydar Pasha, on the Asiatic side of the Straits, the city grew to become an important commercial port for the shipment of cereals, raw silk (exporting 200-300,000 kilograms/220-330 tons per annum), tobacco, and other products.(2)

Population and economic activities

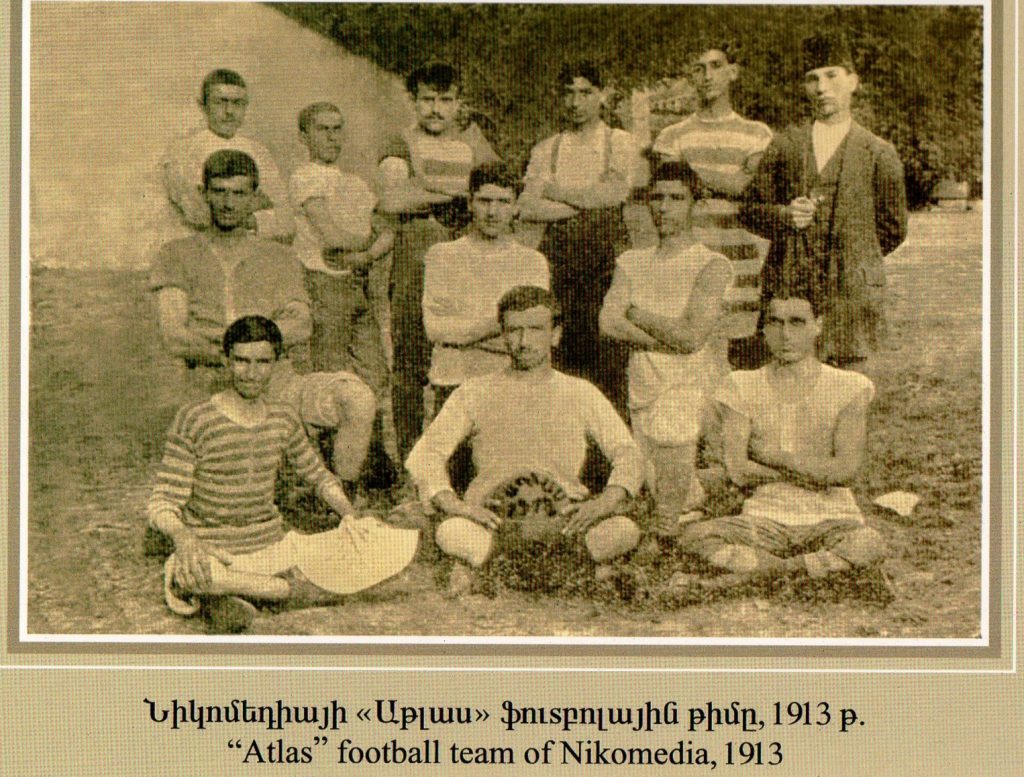

Of a population of 12,000 inhabitants, 4,635 were Armenians in the early 20th century. They resided in the Kadibayir/Karabaş neighborhood, around the Cathedral of the Holy Mother of God in Izmit’s western part. “Izmit’s Armenian population, which was Armenian speaking, was made up of industrious craftsmen and merchants. With the Greeks, they dominated the bazaar, which lay at the foot of the ancient acropolis that looked down on Nicomedia. The chief economic activities were silk-making and the silk trade, as well as the production and sale of tobacco and salt.”[3]

“Regarding the population for the city of Izmid itself, Gasapian shows 6,000 Turks, 4,500 Armenians (900 households), 1,250 Greeks, and 200 Jews.

Persecution and Destruction

On October 8, 1895, 31 Armenians were killed in Akhisar, Izmit sancak, and 55–60 went missing.[5]

Massive Flight and Evacuation

In the early summer of 1921, the retreat of the Hellenic Army was imminent. The Christian population of Izmit had become panic-stricken fearing a wholesale massacre by the Kemalists. It was therefore decided that the civilians were to be evacuated. As a result, a total of 22,000 inhabitants who had sought refuge in the city during the Hellenic occupation in addition to the ca. 10,000 Greek and Armenian inhabitants of the city who wished to be evacuated in order to avoid persecution by the Turkish nationalist movement, left the area.

In the summer of 1921 nearly 33,000 inhabitants from the Izmit region were evacuated to Thrace and the Greek islands Mytilini (Lesbos), Samos and Lemnos. Among these were 21,000 ethnic Greeks, 9,000 Armenians and 3,000 ethnic Turks and Circassians.[7]

According to the British High Commission, they were distributed as follows:

- 7,600 to Volos

- 4,000 to Rodosto

- 3,000 to Pyrgo (Greece)

- 4,500 to Lemnos

- 3,800 to Samos

- 8,000 to Mytilene

The Town of Armash

History

“Several studies assert that Armash was founded by 300 Armenian families from Iran in 1611, on the grounds near the Charkhap’an Surb Astvatsatsin (Warder-off-of-Evil, Holy Mother of God) Monastery, which was built atop a hill, surrounded by charming gardens. Gasapian, however, contends that there was already an existing Armenian settlement, known as Grchla, located on what eventually formed the northern end of Armash. It had been founded by seven families who had escaped from the Jelali rebellions that were still being bemoaned in manuscripts and contemporary chronicles in the mid-seventeenth century. (…)

The inhabitants of Armash were primarily involved in agriculture, raising livestock, and silk cultivation, though a report published in 1915 on behalf of European chambers of commerce noted Armenians also working as architects, carpenters, and quite a few women as milliners.“(8)

Moushegh Sargis Hakobian (b. 1890, Nikomedia, Armash, village Khaskal): Survivor’s Testimony

“We were twelve people in our house. My grandfather, Father Hakob, was the priest of our village St Hakob Church. My father and my uncle were in the Turkish army. They wanted to take me, too. They took me to Constantinople for the medical examination, but my height was too short. I was shorter than the line drawn on the wall. They delayed my going to the army for two years. I went to a village and saw the people who prepared linseed oil. I began working for them. All of a sudden, Turkish officers came; they were looking for deserted soldiers. I ran away, entered a Turk’s cowshed, and hid. A girl came and asked, ‘Where is the boy who makes oil?’

The Turkish woman said, ‘I don’t know. Maybe he is in the village.’ Then when the girl had gone, she said to me, ‘Son, go away. If they catch you, they’ll kill you and me as well.’

‘Oh, God,’ I said and came out.

They demolished our house, plundered what was inside, and took away all the animals. On the road to exile[10], our guards were Chechens without any conscience. While on the road, there came an order to collect a gold coin from each one of us. They were so pitiless that they made us return and walk the same road through hills and valleys again to exhaust us completely. We already had no bread and no water.

My aunt’s husband and young daughter died; there was no food, no drink. I saw with my eyes forty or fifty Armenian girls who, hand in hand, threw themselves from a height into the Euphrates River in order to escape the Turks. They lifted up little infants on their swords and slew them, so that they did not grow up to become mature people. The worst was that my poor grandpa, who was already old, perspired from walking and had to change his clothes. At that time, his gold watch was lost.

As my father and uncle were in the Turkish army, we were permitted to return. We went back on foot, but only few people were left. In this way, we did not reach Der-Zor. We were forced to go to a Turkish village. We settled there. My mother, sisters, grandpa, grandma remained there for three to four years until the end of the war. We worked for the Turks. There was an Armenian woman with us called Yeghisabet. She had told the Turks that the priest’s money was hidden in a tin container. The next day the thieves came in the dark and searched for the gold. They did not find any gold. They filled our clothes into sacks, took them on their backs, and went away.

My grandpa, Father Hakob, died from poverty in that Turkish village. He, who was a priest, had buried hundreds of deceased, was buried without anyone to say the Lord’s Prayer for him.

In 1918, when truce was declared, we went to our village: Khaskal. We saw our house was empty. Then the Greek-Turkish War began. The Greeks came with government soldiers over Izmir, attacked Bursa, and marched forward. With the Greeks were Armenian volunteers under the leadership of Torgom. Kemal entered Izmir and massacred numerous Greeks and Armenians. During Kemal’s time, I was taken into the Turkish army. It was very strict in the army. I served in Constantinople.

Ten thousand Armenians were taken to Greece by ship. It included my mother, my grandmother, three sisters, my brother, and me. First, we were taken to Midilli Island [Gr: Mytilini; Lesvos; Lesbos]. Then we went to Salonica; my uncles were there. We began to work. I became a tanner.

In 1947, we were repatriated to Armenia.”

Source: Svazlian, Verjiné (ed.): The Armenian Genocide: Testimonies of the Eyewitness Survivors. Yerevan: “Gitoutyoun” Publishing House of NAS RA, 2011, p. 413

The Armash Monastery of the Holy Mother of God, the Warder-off-of-Evil (Armashi Charkahap‘an Surp Asdvadzadzni Vank)

“The Armash monastery is located in western Asia Minor, 25 km northeast of Nicomedia [Izmit], at 40°50′ N and 30°11′ E. It was built on an outcrop, near the Armenian village of Armash [Akmeşe] and was surrounded by fine gardens.

Although there had been an Armenian presence in Armash in the 15th century, it is commonly accepted that the population of the village was made up essentially of descendants of the many eastern Armenians that had arrived in the region of Nicomedia and Bursa at the time of the Ottoman-Persian wars in the 16th-17th centuries, and in particular in 1608. This increase in the Armenian population, as well as the resulting economic surge, required the establishment of a local spiritual center and pilgrimage site: this would be the Armash monastery.

The teaching staff and students of Armash played a considerable role in the intellectual and religious life of the Armenians of the Ottoman Empire, providing the Armenian people of Turkey with a large number of devoted churchmen and administrators. With the foundation of a new library in 1889, Armash also became a first-rate cultural center. In 1904, the library held 223 old manuscripts, a number that had already doubled by 1914. The Armenian genocide in 1915 not only resulted in the deportation of the entire Armash congregation but occasioned the pilgrimage site: this would be the Armash monastery.

In 1786, though, a new period began for Armash with the establishment of a religious congregation and a school by Archbishop Part‘ughimeos Gabudiguian. But it was not until the 1860s that the monastery began to play the fundamental role it would continue to have for the Armenians of Turkey until the outbreak of the Great War. In 1864 the establishment opened a printing shop and published the journal Huys, ‘Hope’. In 1866, the Armash monastery broke away from the diocese of Nicomedia, to which it had been attached, and became an autonomous abbey. The principal architect of this change, Father Kevork Aliksanian, became archbishop of Armash in 1869. In 1872 he completed the construction of a new church, begun in 1866. His successor, Khoren Ashekian (Խորէն Աշըգեան; 1842-1899), founded a boarding school at the monastery, Ghevontiants School. The school’s success, the development of the printing works equipped with new machines from Europe, and the intellectual potential concentrated in the monastery made these years a promising period. The aftermath of the Russo-Turkish war of 1877-1878 was nevertheless a disaster for Armash: in particular, the school was closed and publication of Huys stopped.

Despite serious difficulties and modest means, Archbishop Khoren Ashekian, managed to turn the monastery around, re-open the school and lead Armash to its apogee. But, on 27 September 1888, a major fire destroyed a significant part of the village as well as the south wing of the monastery, which housed the boarding school. The accession of Mgr. Khoren Ashekian to the patriarchate (as Khoren I, 1888-1894) immediately afterwards enabled the damage to be repaired rapidly, though. Because the Armash monastery had been directly attached to the patriarchate since 1866, Patriarch Khoren was able to fulfill his ambition to make it a major intellectual center, a ‘Venice of the Armenians in Turkey’, referring to the role this town had played since the 16th century in the development of Armenian printing and letters in Europe. In the 19th century, particularly with the promulgation of the Armenian National Constitution in 1863, the Armenian patriarchate of Constantinople became a central institution in the religious, political and cultural life of the Armenians of the Ottoman Empire. It was therefore indispensable to open a modern seminary for training future religious and intellectual leaders of the Armenian nation living in the Empire. And so in 1889 the great seminary of the Armenian patriarchate of Constantinople was inaugurated in Armash.

Replacing Patriarch Khoren at the head of the monastery, Archbishop Maghakia (Malachia) Ormanian (Մաղաքիայ Օրմանեան; 1841-1918) undertook major work there: he erected a large building to house the seminary, whose direction was entrusted to Father Yeghishe Turian (Durian; Tourian; 1860-1930), who constructed several outbuildings, opened a silkworm-breeding station, planted mulberry groves and installed a watermill. His seven years of service (1889-1896) were the highpoint in the life of this institution. The massacres of 1895 temporarily put a damper on this dynamic: Ormanian and Turian, as well as many teachers and students were forced to leave Armash, where the interim was ensured by Father Nerses Der Partughimeossian. During this time of tension and insecurity, pilgrimages became more difficult and infrequent. With Ormanian’s election to the patriarchate in 1896, however, Armash monastery was granted a monthly patriarchal subsidy, which enabled it gradually to resume its activity. Now archbishop, Yeghishe Turian – later to become patriarch of Constantinople in 1909 and of Jerusalem in 1921 – became superior of the monastery in 1898, a post that would be held from 1904 to 1907 by Father T‘orkom Kushaguian, who would succeed Mgr. Turian in 1929 as patriarch of Jerusalem. The upheavals accompanying the Young Turks’ revolution in 1908 affected Armash as well, causing a sudden slowdown in its activity. It fell to Father Papguen Gulesserian, future coadjutor of the catholicos of the House of Cilicia, Sahag II to stabilize the situation and to breathe new life into the institution. His work would be continued until 1915 by Father Mesrob Naroyan.

The Armenian genocide in 1915 not only resulted in the deportation of the entire Armash congregation but occasioned the destruction of the inestimable riches assembled there.

(…)

The Armash monastery was plundered in 1915, then confiscated after the Great War and left to the devices of all comers. Destruction of the church and adjoining buildings began upon the occupation of the site by the Kemalists in 1923-1924; part of the remaining walls were used to build a first mosque in its place, which was replaced in 1994 by a new and larger edifice. The seminary building was still standing in the 1990s. But, damaged by the 1999 earthquake, it was demolished the same year. Standing empty and in ruins, a small portion of the outbuildings, housing in particular the old printing works, was still visible in 2011. It had long been used to store unwanted items. At the same date the fountain and, further on, the abandoned mill house could also still be seen.”

Source: Union Internationale des Organisations Terre et Culture, https://www.collectif2015.org/en/100Monuments/Le-monastere-d-Armache-ou-de-la-Sainte-Mere-de-Dieu-Destructrice-du-Mal/

A Model Child Colony: The Vocational Orphanage of Ermişe

Since 1917 the monastery premises were used for an ambitious re-education project of the nationalist war regime of the Ittihat ve Terakki Cemiyeti (C.U.P., alias Young Turks):

„Based on the original project, each and every town from the Ottoman provinces would send ten orphans to the colony. After finishing their theoretical and practical education on agriculture, they would go back to their villages. In the end, the town would be inhabited almost entirely by eight to ten thousand orphans over the age of thirteen. These rural children would be equipped with both theoretical and practical agricultural training. After completing their studies, some of them would form and live in pilot villages, while others would go back to their own villages in order to modernize agricultural production. Based on the initial project, an Austrian company would establish nine different factories in the colony. In other words, Armash would not only be an agricultural colony but also become an organized industrial zone. Moreover, orphan girls and boys of the colony would be married to each other, and thus ‘the town of orphans’ would become ‘the village of felicity’ (saadet köyü).

As can be imagined, none of these grand plans – such as training ten thousand children, establishing nine different factories, or bringing in orphan girls as the prospective wives of orphan boys – could be realized. The Armash agricultural orphanage was opened in early 1917. It was relatively big, with about six hundred, mostly Armenian orphans, learning and practicing mechanized agriculture in four separate departments honoring the key rulers of the Empire: Reşadiye, Saidiye, Talatiye, and Enveriye.”

Quoted from: Maksudyan, Nazan: Ottoman Children & Youth during World War I. New York: Syracuse University Press, 2019, p. 43