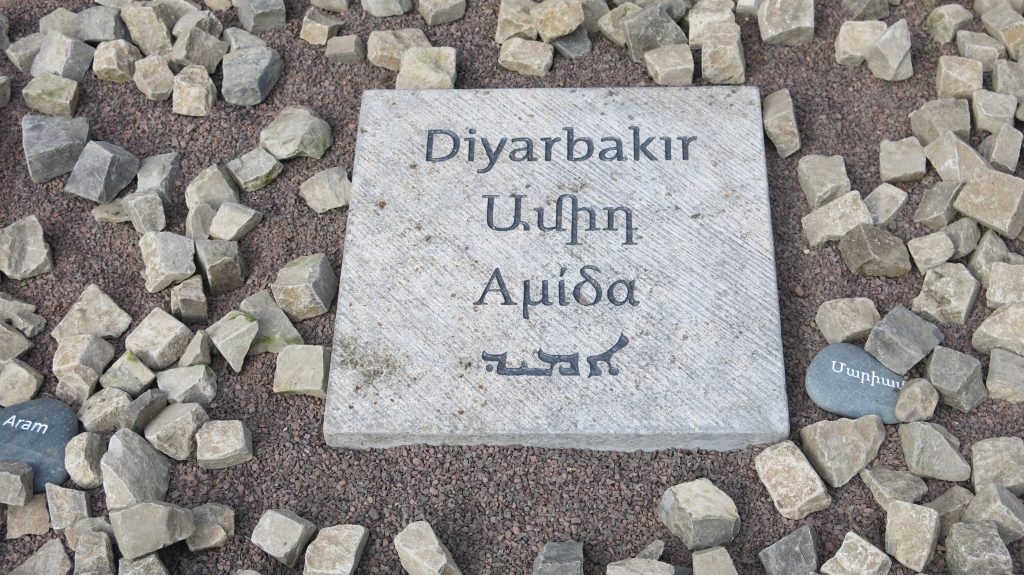

Diyarbekir, the Black City

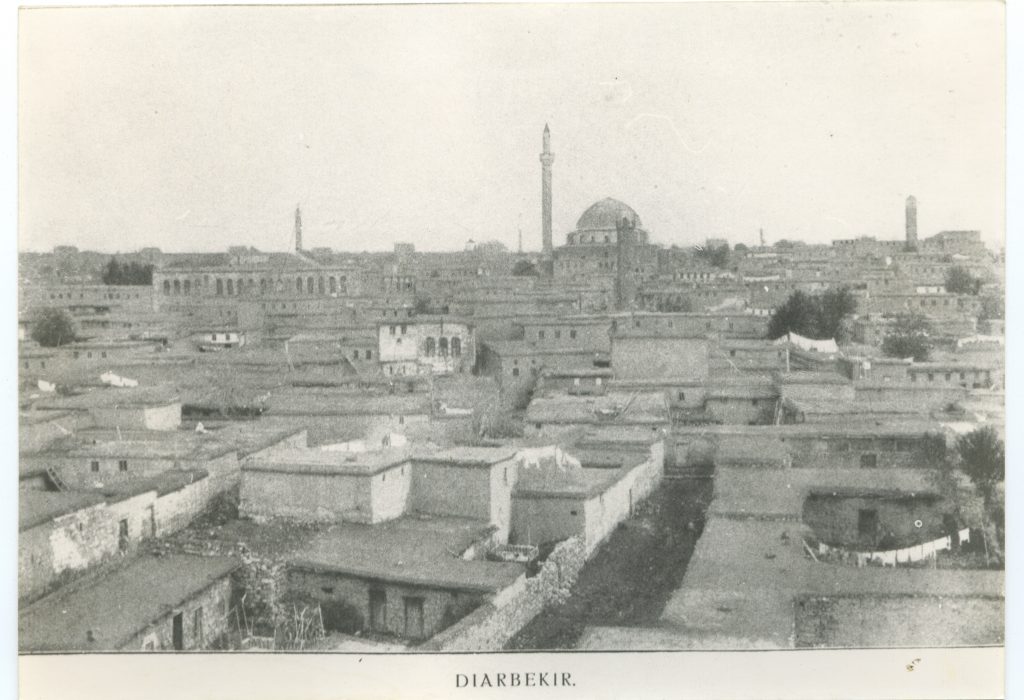

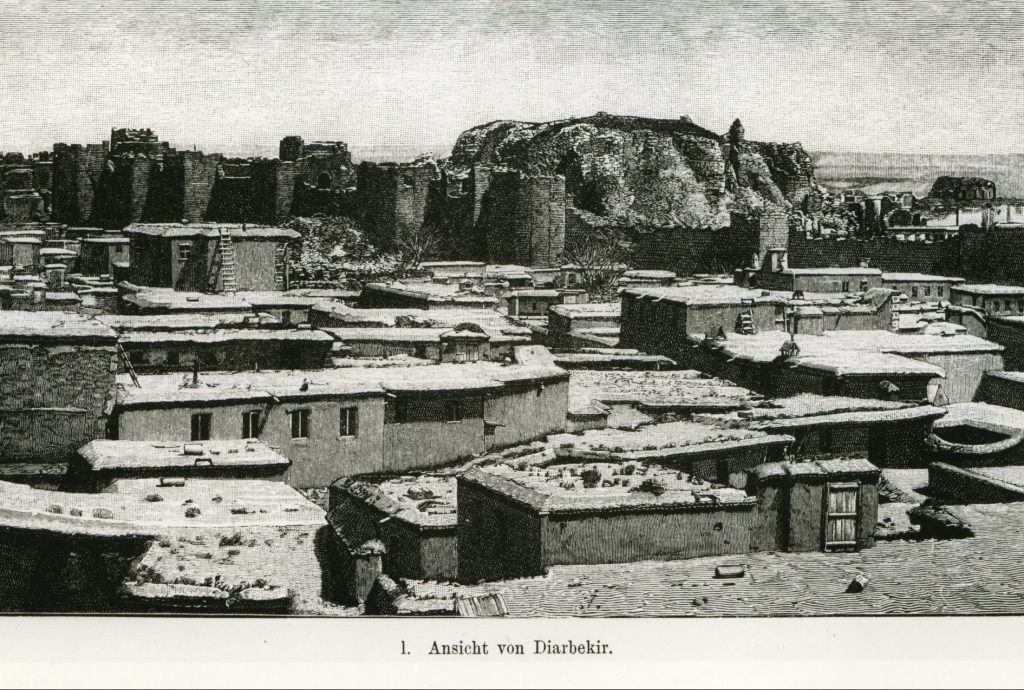

“Diyarbakir was for a long time the Ottomans’ key city along the Asian border. Situated on the caravan routes tying Asia Minor to Mesopotamia, its position was strategically an important springboard for conquest. For this reason, throughout its history, it was the subject of bitter disputes between Persians, Byzantines, Armenians, Arabs and Ottomans. Diyarbakir has always been a cosmopolitan city, where all peoples of the region are represented, and early on, it developed the conditions that would allow the rise of a sedentary, urban, wealthy and enlightened society.

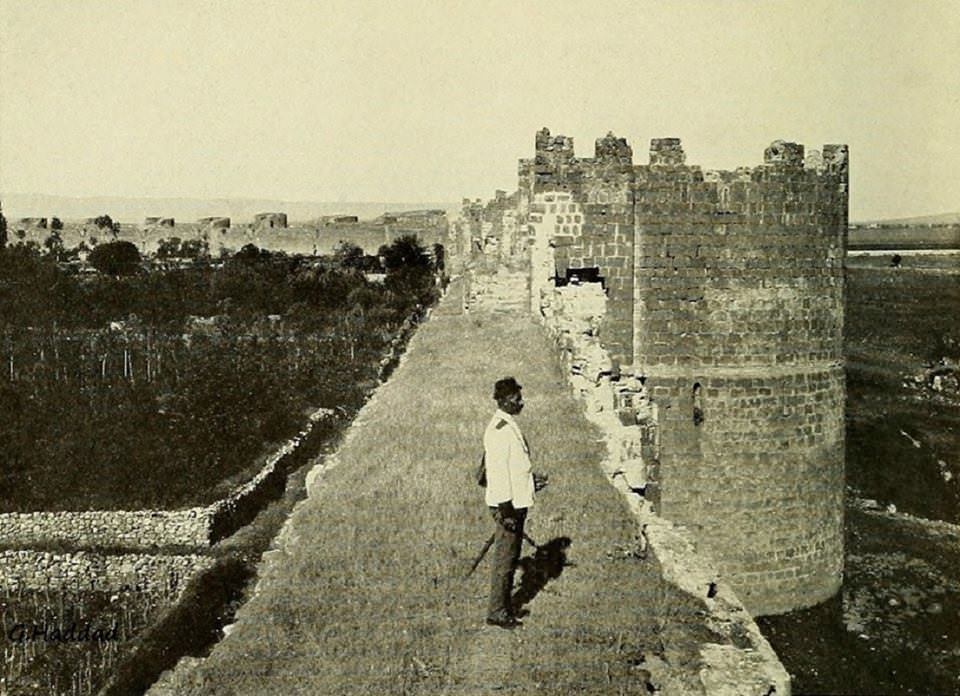

The city seemed austere and somber because of the color of the basalt stones been used in its construction. All its neighborhoods were enclosed by high walls which completely isolated the city from the outside. (…) When [Reverend] Buckingham visited it in 1827, he wrote of four gates in the walls (…). The gates were used to isolate and protect the city in times of trouble. During the great Kurdish insurrection of 1847, the routed Ottoman army was forced to take refuge inside the walls, since the Kurds had occupied the roads, ‘sowing destruction and murder’. In contrast, these same gates were used as a deadly trap for the Christians during the first great massacre of 1895.

The streets were narrow, winding und filthy, the air unhealthy. Only a few streets in the center of town were paved, and along these were located the most beautiful homes, notably the Governor’s palace and the bishoprics, including the Syriac Orthodox. In 1842, [Reverend George Percy] Badger stated that Diyarbakir had no ‘Jacobite’ bishop, because the city’s diocese was under direct control of the Patriarch residing in Mardin. It was the arrival of foreign consulates that would later favor the creation of an independent diocese.

‘The Catholic and Jacobite Syrians also have a bishop at Diyarbakir, while at Mardin the former have an archbishop and the latter a patriarch. The Gregorian Armenians have a parish priest at Diyarbakir, the Armenian Catholics have an archbishop at Mardin and a bishop at Diyarbakir. […] The Armenian Protestants come under the American mission, whose seat is at Mardin, and they have a pastor at Diyarbakir. The Chaldeans have an archbishop in both cities. The Greek Orthodox have a Metropolitan at Diyarbakir, and for their part, the Greek Catholics have missionary monks.’[1]

The Myriamana church, or the Church of the Virgin, the largest church in the city, belonged to the Syriac Orthodox. The Gregorian Armenians owned two ‘richly decorated’ churches, the Armenian Catholics had one, as well as a monastery kept by the Capuchin Fathers. The Greek and Syriac Catholics each had their own church.

Unlike in Mardin, the Christian communities were huddled in the same neighborhoods, following the traditional urban organization for cities under the Ottoman Empire, and for the Muslim world in general. All Christians spoke Armenian and Kurdish, often in addition to their maternal languages, and the ecclesiastic authorities and town notables spoke Turkish. In the bazaars, markets, and poor neighborhoods, the language was Kurdish.”[2]

Population

In 1827, Reverend James Buckingham estimated the city’s population at 50,000, with Muslim Ottomans (Turks and Kurds) as majority. 1,400 families were Christian, of whom about 1,000 were Armenian and 400 were Syriacs (Syriac Orthodox, Syriac Catholics and Chaldeans). Most of the Syriac families were ‘Jacobite’ (Syriac Orthodox). Buckingham also counted a small Greek Orthodox community of 50 families.[3]

“Several decades later, the statistics produced by Vital Cuinet in 1891 showed a slight decline in numbers, with only 950 individuals for the ‘Jacobites’, and 400 for the Catholic Syrians. But these numbers seems excessively low.

This collapse in Syriac demographies, including the ‘Jacobite’, might be explained by emigration, which had already been reported, to safer cities such as Urfa, or even Istanbul, where a large Orthodox Syriac population was already living. This migratory flux would not however explain everything (…). It is possible, moreover, that some Syriac families could have been confused for Armenian families and counted as such because of the communities’ proximity and because they all spoke Armenian.”[4]

According to the Armenian theologian and archbishop Mesrob M. Krikorian, Diyarbekir in the period of 1860-1908 was “inhabited by 10,260 Armenians who constituted one-third of the whole population of 35,000. As the offices of the central government of the province were situated in the town, Armenians took an important part in the local life, contributing much to the political administration, justice, finance, technical affairs, education and public health.”[5]

According to the census of the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople, there lived 16,352 Armenians in 25 localities of the kaza Diyarbekir before the First World War, maintaining 10 churches, one monastery and eleven schools with 1,300 students.[6]

Destruction

In an estimate presented at the Paris Peace Conference (1919), the Syriac Orthodox Patriarchate put the number of massacred Syriac Orthodox Christians in the “city of Diyarbekir and its surroundings” at 5,379 and the number of destroyed villages at 30.[7]

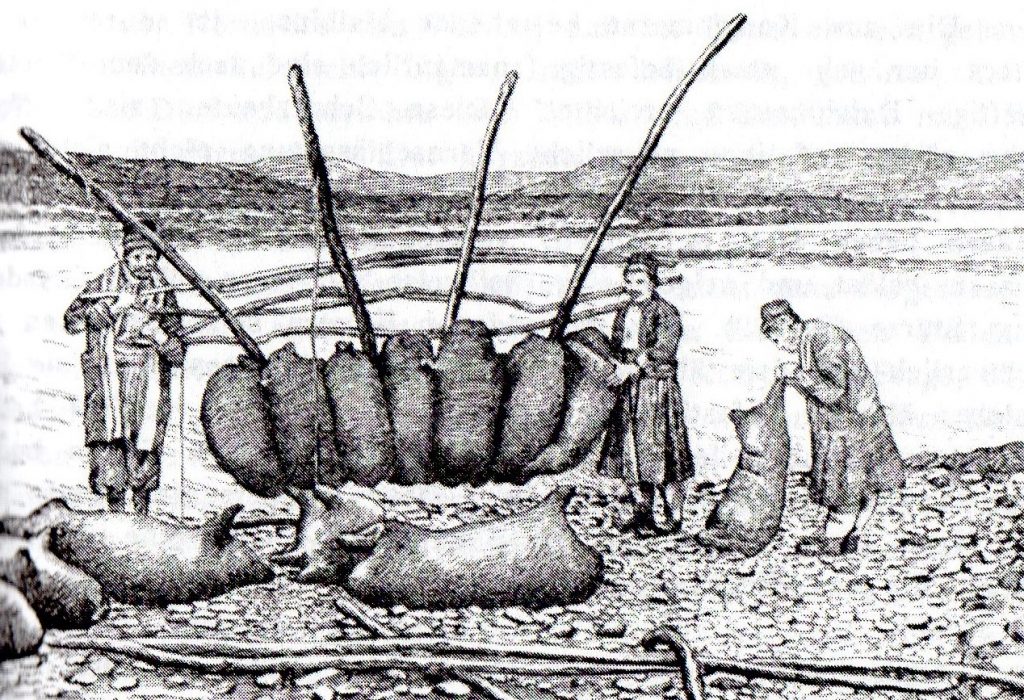

“In Diyarbekir a commission had arrived from Constantinople ‘to study the Armenian question’. It was headed by the chief of police Bedri Bey; you can imagine what came out. Immediately, a fierce persecution of Dashnaktsakan and other respected Armenians began. They were tortured in prison and a number were killed every night. Two Armenian doctors were forced to certify that the cause of death in all cases was ‘typhus’. Five priests were stripped naked, smeared with tar and led through the streets. Half an hour outside the city, between the Murad Fortress and the Tigris River, 2000 Armenians were massacred at once. The number of arrested notables exceeded 700. One day the gendarmerie commander appeared and announced to them that an imperial order banished them to Mosul, where they would remain until the end of the war. They were delighted, took money, clothes and furniture and embarked for Mosul on the so-called ‘keleks’, wooden rafts resting on inflated skins, like those used by the inhabitants of the area to cross the Euphrates and Tigris rivers. Some time later, it was learned that they had all been drowned in the Tigris River and that none had reached Mosul. The authorities continued to ‘send down’ and kill one Armenian family after another, men, women and children. Sheikh Faiz el Ghusayn (1883-1968) lists a number of the richest Armenian families who were deported on the Tigris boats by name. Among the 700 arrested was the Armenian Catholic bishop Homandrias, a venerable, learned old man of eighty. The Turks felt no reverence even for his white hair and drowned him in the Tigris.”(9)

Excerpted and translated from: Zurlinden, Samuel: Der Weltkrieg. Vorläufige Orientierung von einem schweizerischen Standpunkt aus. Vol. 2. Zürich: Art. Institut Orell Füssli, 1918

Rafael de Nogales: The City of Diyarbekir in 1915

“Raising my eyes, I saw opening at my feet a beautiful valley, set with meadows and blossoming fields as if encrusted with gems; while far above, on a mesa of the opposite slope which fell almost perpendicularly to the depths of the plain, a dark mass of battlemented ramparts constructed of blocks of black basalt loomed like a crown of death. It was Djarbekir of the Arabs, the Kara-Amid or ‘Black Amid’ of the Ottomans, capital of the province of that name and the head of navigation of the Tigris. (…)

Djarbekir possesses, in addition to her thirteen caravansaries and dozen or so public baths, eight or nine churches, among which the Nestorian convent mentioned above is noteworthy as are also, for various reasons, the Greek Orthodox Church of the Melekites, the very celebrated Jacobite Church of Holy Mary, and likewise another, the name of which escapes me, which I found turned into a stable. This I discovered the following day, when I went to visit my horses and found them tied to the Great Altar, in company with animals from various squadrons which occupied the rest of the sanctuary!

Among the thirty or forty mosques, several are adorned with decorative details carried out in beautifully carved stone and with superimposed ornaments and ogive arches, strewn with sparkling crystal ornaments. The most beautiful and most original of all is the justly famed Ulu-Djamissi, or Great Mosque, which some commentators believe to have been constructed from the remains of the famous Church of St. Thomas upon the ruins of the palace of Tigranis. Like many Christian shrines of this district, transformed by the Mohammedans into mosques, the Ulu-Djamissi is adorned with a minaret three or four stories high, square, and pierced with window-like apertures; all of which reveals at first glance the characteristics of the ancient steeple. Its greater nave, similarly, is not oriented to the south, as it should be; another fact tending to demonstrate its purely Christian origin. (…)

The most beautiful portion of the mosque in question is undoubtedly its great tiled court, centered by a fountain in the shape of a kiosk, and bordered on the north by a group of colums, monolithic to all seeming and in part sunken, crowned with Corinthian capitals. To the east is a double gallery or double architrave of columns, beautiful and severe in line, interrupted by the principal entrance of the mosque; and to the west, another gallery of superimposed columns of Hellenic order, but covered with fantastic and extravagant designs which must have been the equivalent, two thousand years ago, of what are today vulgarly called cursi modes: the style of the noveau riche. In fact King Tigranis, of whose palace that court formed part, seems to have been considered by the ancient Greeks as a sort of barbarian who, without ever attaining to a comprehension of the serene beauty of Hellenic art, believed that he might render that art perfect by adding to its chaste forms details and adornments of his own taste. This celebrated façade, which has given the archaeologists so much to think about, merely represents according to my way of thinking the fantastic vision of a rustic mind, traced and carved in marble by the admirable chisel of one of the numerous Greek artists whom King Tigranis had doubtless brought, along with his 300,000 other Graeco-Roman prisoners, from Cappadocia, in order that this sculptor might help construct the palace of Djarbekir. (…)

As a result of the extermination of the Armenians, who were the nucleus of its artisan and merchant classes, the bazaars of Djarbekir were almost deserted at the time of my visit; and the city’s rich industries of tapestries, Moorish leather, silks, and woolens, were practically paralyzed. Only the products of the fields – as for example wheat, barley, tobacco, cotton and fruits (among the latter the great, luscious honey-dripping melons and sandias for which Djarbekir is famous) – and likewise the coal and copper from the Komur-Hane and Argana-Maden [Ergani] mines, continued normally. This trade was thus the sole basis of life-giving commerce for a city of thirty thousand inhabitants, which even before the war had been composed for the immensely greater part of Turks, Kurds, and Turkomans: all of them purely Mohammedan elements.

Of the four gates piercing the encircling city-wall, the most beautiful is the Gate of Aleppo, or Rum-kapu, which, in addition to an enormous inner door of iron, displays rich and gorgeous inscriptions in diverse characters and languages, intermingled with Greek niches and Roman eagles. Thanks to its position as a terminal point or head of navigation, Djarbekir from time immemorial has played her part as caravan center and place of transport, from which Syrian and Anatolian merchants continue sending merchandise down to Baghdad on rafts constructed upon air-filled bags of sheepskin or buffalo-hide. Such in brief is the description of Djarbekir, the Black City, which thanks to its commercial importance ranks as one of the most important cities of the Ottoman Empire, and which is that Empire’s most advanced outpost upon the desert plains of Djesiret, or northern Mesopotamia.”

Excerpted from: Nogales, Rafael de: Four Years Beneath the Crescent. Translated from Spanish by Muna Lee. London: Sterndale Classics, 2003, pp. 119, 122-124

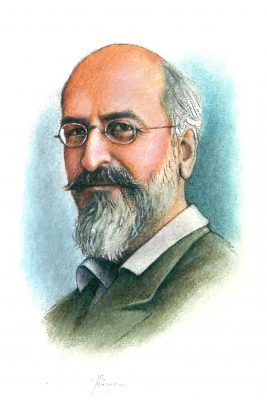

Intra: 1921 – Death of a Poet at the Bank of the Tigris

Intra (Western Armenian pronunciation: Indra), born in Constantinople in 1875 as Tiran Chrakyan or Charakyan (Tiran Č'(a)rak’ean; Տիրան Չ[ա]րաքեան), went down in Armenian intellectual history as a poet, author of essays as well as a painter and teacher. He received his education at the Berberian College in Constantinople and subsequently graduated from the College of Arts, where his works were appreciated by the Armenian-Russian painter Hovhannes (Ivan) Aivazovski. Intra drew his collection of essays Inner World (1906) and his sonnet cycle Cypress Land (1908) with the anagram of his first name; his artistic, sometimes manneristic Western Armenian is a challenge for any translator.

As Adventist of the 7th Day, Intra had belonged to a tiny denominational minority within the Armenian community since 1913. His accession seems to coincide with a spiritual crisis that intensified with the beginning of the World War. The Adventist Church in the Ottoman Empire had been founded in 1893 by the Armenian Zad(o)ur Baharian (Zadowr Baharean); he presided over the congregation, which was initially banned until 1908, for the rest of his life. About 250 of the 450 Ottoman Adventists died during the genocide, among them the deported Baharian, who was shot in an ambush near Sivas by Kurdish irregulars.

After the genocide of 1915, Intra completely lost his mental balance, broke off his teaching and moved through the provinces as the successor to Baharian, eagerly preaching peace and unity. The Adventist community at that time had less than one hundred believers, most of them in Constantinople.

The Kemalists arrested Intra in 1921 and deported him. According to the testimony of a fellow sufferer, the poet lost his mind during the thousand kilometers march that began in Konya. In 1921, at the end of his strength, Intra sent letters and notes written on paper to the brothers and sisters in faith. Shortly before his end, he wrote with a trembling hand the words of the 23rd Psalm, verse 4: “And when I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil, for you, my God, are with me.” Shortly afterwards Intra died, exhausted and emaciated, on the banks of the Tigris near Diyarbekır.[8]

Haykaram Nahapetyan: Diyarbakir 100 Years after the Genocide

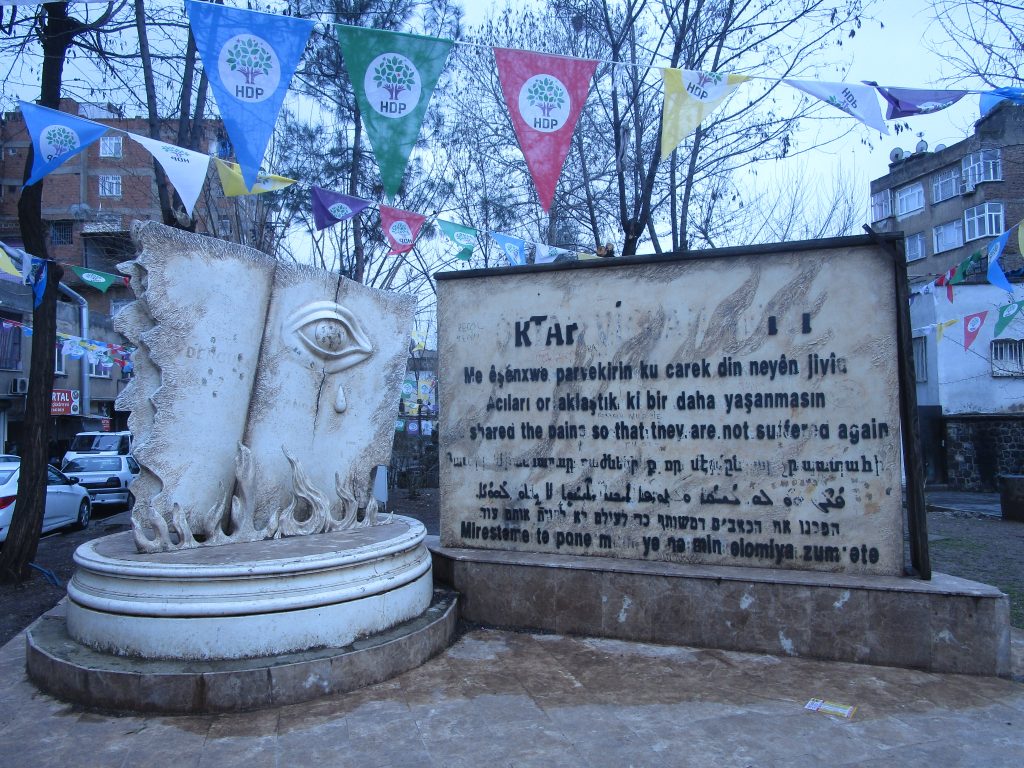

If Turkey ever officially faces the Armenian Genocide, the recognition will begin from the East of the country and not from center or West. The City of Diyarbakir, the ‘capital’ of Turkey’s Kurdistan, is the most advanced city in Turkey in terms of facing the historic reality of the Genocide. Indeed, the role of human rights activists and intellectuals of Istanbul and other settlements should and cannot be underestimated. But there is no political administration, other than the authorities of Kurdish-populated ones that would openly speak of what had happened to the Armenians and call for repentance.

Diyarbakir’s administration established street signs in Armenian language, opened Armenian classes in 2012, the Seftali street officially renamed Megerdich Margosian street, who was a prominent ‘bolsahay’ (Istanbul Armenian) author. On 13 November, 2011 Nursel Aydogan, member of Turkey’s parliament (meclis) from Kurdish HDP party from Diyarbakir, submitted a petition to rename the Sur district of the city to Dikranagerd: the historic Armenian name of the place. According to parliament’s website the petition is still under discussion at the Internal affairs commission.

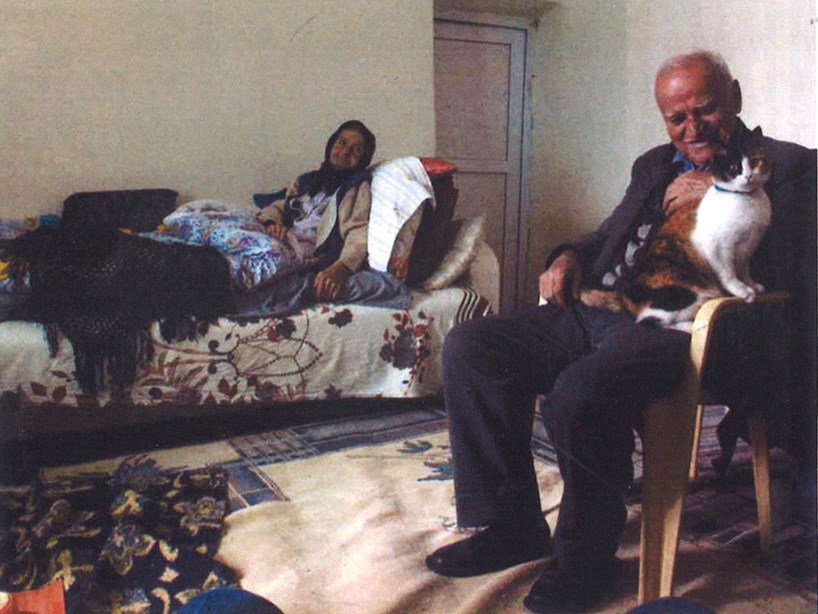

Eighty percent of ‘diarbekirtsis’, who attend the Armenian language classes, are reportedly Islamized Armenians. They used to be called crypto-Armenians before. Not in Diyarbakir anymore: in historic Dikranagerd more locals unveil their Armenian roots, even convert to Christianity and baptize at Armenian-Apostolic churches – turning from crypto-Armenians to new-Armenians. The deacon of Diyarbakir’s newly-renovated St. Giragos Church Armin Demerjian himself, until recently had a very much different name: Abdur Rahim Zorusselan.

Diyarbekir’s municipality supported (also financially) the reconstruction of city’s St. Giragos Armenian Church. Apparently, Turkey’s government also has a record of reconstructing an Armenian spiritual temple: the Holy Cross church on Akdamar island of Van in 2007. However, Ankara authorities attempted to make a show out of it by putting huge Turkish flags (but no Armenian Cross) on the church. And certainly there was no Armenian flag on the whole island. The Turkish government refused to open the border-gate even for a short period of time or arrange a direct flight from Yerevan to Van for the opening ceremony day. The Armenian delegation from Yerevan had to drive all the way through Georgia.

But Diyarbakir leaders did not strive to make a PR out of church’s reopening. The reconstruction of St. Giragos was rather a step to approach their Armenian fellows and to reconcile Turkey with Turkey’s past. ‘Pari yegaq dzer dune’ Armenian posters were seen in the city during the ceremony.

The Kurdish leadership, including the one in Northern Iraq, has truly invested lot of efforts in democratization. Kurdistan has fairly good chance to turn into the locomotive of democracy in the Middle East. According to The Economist, ‘Democracy in the Kurds’ region, though imperfect and tainted with corruption, functions far better than elsewhere in Iraq.’

Iraq’s Kurdish leadership sent a delegate to Paris in March, where the Congress of Western Armenians was taking place. A member of Iraqi Kurdistan’s parliament Ali Halo apologized for the Kurdish participation to the Armenian Genocide. The Armenian language has become one of the official languages of Iraqi Kurdistan.

The Kurdish authorities could take one more historic step in terms of bringing the Turkish Republic and society closer to facing their history. Diyarbakir has a chance to become the 1st city of modern Turkey to take position on recognizing and condemning the Armenian Genocide. Out of 92 members of Diyarbakir’s city council about 60 belong to Kurdish BDP party. Although the city council involves several members of the ruling AKP party, who theoretically should resist such recognition, the BDP politicians apparently outnumber.

On 24 April (2015) six non-governmental organizations held commemoration in Diyarbakir and called for recognition of the Armenian Genocide. ‘It has been a century-long time that the political vision of CUP leaders put a disgrace over our shoulders‘, Kurdish leader Selahettin Demirtaş stated at the ceremony next to the ruins of St Sarkis Armenian church. Although different Kurdish public and political figures in Turkey have made statements openly calling the events of 1915 a Genocide, there was no formal recognition by any administration of Turkey since Raphael Lemkin had coined the term.

It would be very much proper and fitting to vote for such resolution in 2015, the centennial year of the Armenian Genocide. In past, there were many occasions when the Armenian Genocide has been recognized on city council level: Edinburg (Scotland, UK), Cardiff (Wales, UK), Batak (Bulgaria), Milan (Italy), Rome (Italy), etc. In fact, the formal decisions adopted by various Italian city-halls eventually turned to be a major boost pushing Italy toward formal recognition of the Armenian Genocide in November of 2000. Will the same scenario work for Turkey? It may, or it may not. But in any case, it would be the right thing to do launching an important process in modern Turkey.

Hundred years after 1915 Dikranagerd could change history and make a critical stride toward healing the pain of the Armenians, and promoting the piece between the Armenians and Turks based on truth and justice.

Indeed, this will be a huge step in bringing democracy and openness to Turkey itself.

Quoted from “Asbarez” (Paris), 30 April 2015, http://asbarez.com/134670/diyarbakirs-city-council-should-recognize-armenian-genocide/