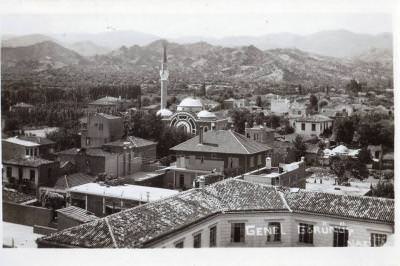

Toponym

Nazilli is a Turkish name that has somehow evolved from the former (also Turkish) name of Pazarköy (market village). According to legend, the son of Aydın‘s governor in the Ottoman period, fell in love with a young woman from Pazarköy but was rejected by the girl’s father. The young man later named the town Nazlı Ili (Nazlı’s Home) after his loved one. The 17th century Ottoman traveller Evliya Çelebi held that the town was named for the capriciousness (‘naz’) of the local women in this wealthy town. Or it could have been the name of a family of Oghuz Turks that settled here.

Nazilli was still called Nazli by the British as of 1920.

History

The inhabitants of Nazilli / Nazli practiced weaving and thus planted cotton in the area for this purpose. The Oghuz Turks were succeeded by the Anatolian beyliks of Menteşe (in 1280) and then Aydinids.

In 1390 sultan Bayezid I brought the area into the Ottoman Empire. At this time, the town comprised two villages, Cuma Yeri (Friday Square) and Pazarköy (Market Village). The town was only later referred to as Nazliköy. In 1402 Tamerlane defeated Bayezid at the Battle of Ankara and took control of the Aegean region, giving the Nazilli area back to the Aydinid family. It was quickly recovered for the Ottomans by Sultan Murat II.

During the Turkish War of Independence, Nazilli was occupied by Greek forces and came under Turkish control on 5 September 1922.

War and Biased Allied Inquiries: 1919-1922

In the course of the fighting between the Hellenic occupation forces, which were originally intended to protect only the Christian population in the sancak of Smyrna, and Kemalist (‘nationalist’) units as well as local irregular gangs, there were attacks and crimes against the civilian population on both sides, with the massacres, expulsions and burning of Greek neighborhoods that began on the Turkish-Muslim side having a tradition going back to 1914. A documentary by the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople quotes a letter of 1914 of the mutesarrif of Aydın, Hüsni Bey, to the officer commanding the prisons of Smyrna, mentioning ‘instructions’ by the C.U.P. for the arrest of ‘pro-Hellenes’, among them arrestees from Nazilli.[1]

“Meanwhile, Greek forces were pushing inland. At Nazili, occupied on June 3 [1919], Greek troops exposed ‘certain parts of their body to the Turkish women’. According to the Turkish authorities, a Turk who complained was shot. The Turks further charged that the Greeks systematically searched for arms, stole belongings, and killed householders.

Near Nazili the Greeks reportedly killed forty Turkish hostages. Villages in the area suffered greatly as they changed hands between warring parties. Over the summer Nazili experienced heavy shelling. According to the Turks, 200 Muslim girls were raped and then murdered there, while other villages were torched. The Turks also accused the Greek army of levelling Aydın town and massacring civilians there.

But the story was more complicated. When Turkish irregulars retook the town in July [1919], armed locals joined in, firing from rooftops and windows at the retreating Greeks. In retaliation, they set fire to the Turkish quarter. The Turks then torched the Greek quarter and massacred the remaining inhabitants. Even [the British historian and journalist Arnold] Toynbee refused to sugarcoat what the Turks did to Greek noncombatants: ‘Women and children were hunted like rats from house to house, and civilians . . . were slaughtered in batches—shot or knifed or hurled over a cliff. . . . Many of the women . . . were violated.’

The retreating Greek units refused to allow Greek locals to leave with them; they were subsequently deported to the interior by the Turks. The Turks took thousands of Greeks hostage in Denizli and Nazili, threatening them with massacre if more Muslims were killed. Nonetheless Constantinople complained and the Allies, submitting a detailed summary of Turkish casualties for investigation. According to the complaint, in ‘the City of Smyrna and the Surrounding Districts,’ 675 Muslims were massacred and 34 were ‘lost,’ while 13 girls were ‘violated.’ (…)

The Allies established a commission of inquiry chaired by Bristol(2), which also included three generals, British, French and Italian. They spent August–October 1919 questioning Allied officers, Turks, and Greeks. Overall, the commission endorsed the Turkish version of events but also found fault with the Turks. ‘The Greek command tolerated the actions of the armed Greek civilians [in Smyrna] who, on the pretext of helping the Greek troops, freely pillaged and committed all sorts of excesses,’ according to the report. But the report also charged the Turks with massacring ‘some Greek families’ in Nazili. The commissions accused the Greeks of ‘numerous outrages and crimes’ during the evacuation of Aydın, where the Turks, led by one Yuruk [Yörük] Ali, were charged with torching the Greek quarter. They ‘pitilessly shot down a great number of Greeks.’ The commission affirmed the Turkish charge of a Greek massacre in Menemen but said that it wasn’t organized by the Greek command and was a result of panic. A separate French investigation concluded that 200 Turks had been murdered there.

The commission made no mention of some 3,000 Aydın Greeks—men, women, and children—allegedly murdered, nor of 800 women and children deported inland. ‘Now Aidin is a vast cemetery,’ the Greek Patriarchate lamented.

The commission concluded that responsibility for the Greek atrocities lay chiefly with the Greek army. The Turks were held partially responsible for what happened in Smyrna city because the local authorities had failed to prevent criminals escaping from prison and taking up arms before the Greek army arrived. Importantly, the Greek army had advanced beyond the sanjak of Smyrna, to Aydın, Manisa, and Kasaba, outside the remit of the Allied authorization.

The Greek invasion, mounted ostensibly to maintain order, turned into a ‘conquest and crusade,’ the report said. The commission ruled that the annexation by Greece of the areas occupied would be ‘contrary to the principle proclaiming the respect for nationalities’ and proposed that the Greek army be replaced by Allied troops.

Although the report blamed mutual ‘religious hatred’ for persecution on both sides, it was hardly impartial. Bristol had already reached his conclusion months before the investigation. In May 1919 he wrote that the Greeks’ behavior was ‘disgraceful,’ that ‘they murdered Turks . . . [and] forced’ captured Turkish troops ‘to sing out ‘Long live Venizelos’ in the Greek language. They killed some of these soldiers [and] . . . killed people and looted houses and shops in the surrounding villages.’ The report was never published, but it certainly affected Allied officials’ attitudes during the following months. The next three years or so the Greek zone of occupation were more or less tranquil.”

Excerpted from: Morris, Benny; Ze’evi, Dror: The Thirty-Year Genocide: Turkey’s Destruction of Its Christian Minorities, 1894-1924. Cambridge, Massachusetts, London, 2019, pp. 431-434

Destruction

Deportees from Aydın

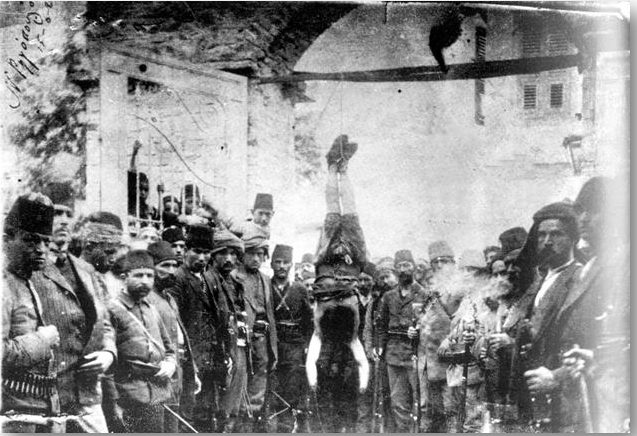

“(…) nine of [the 800 deportees from Aydın] who had stayed at Nazli were shot by order of the brigand chief, the bloodthirsty Yuruk [Yörük] Ali. This scoundrel had gone into a Christian house, situated opposite the church, and being in a gay mood, he tried to shoot down the cross on the roof of the church. But he missed it, and he became furious, and then he ordered that all the prisoners should be put to death. His order was about to be executed when the mufti of Nazli, moved by really humane sentiments, appeased the brigand’s fury, by delivering to him nine of the youngest and richest prisoners. Among those who then perished at Nazli, was the Archimandrite Matheos Pavlidis of the Church of Jerusalem, who thus suffered a martyr’s, death.

But the sufferings of the unhappy prisoners of Nazli and Denizli were not yet at an end. Such wild scenes of horrors are seldom to be met in history. An official report based on correct information, give the following narration:

‘On the evening of June 11 1920, the notorious rebel chieftain Demirdji [Demirci] Efe, on hearing of the advance of the Greek army, demanded a sum of 8000 gold liras from the Greek community in order to procede for their safety. He then ordered the people to assemble and prepare for departure. Demirdji’s men, some in soldier’s uniforms and others dressed as brigands, went through the Greek quarter on the previous evening and catching those who did not wish to leave their homes conducted them to their chief.’”[3]

Deportation and Massacres of the Greek inhabitants of Nazilli, 1919-1920

“ (…) officers of the Turkish army and of the gendarmerie, as well as various other irregular soldiers or deserters, staying at Nazli, joined the peasants of Lower Nazli in looting the Christian shops in the market and the Christian houses. The Turkish inhabitants of the upper quarter during this time abandoned their houses and carried their furniture away. Men and women hiding in their houses at the time of the looting were killed as soon as they were spired out. Their disfigured corpses were subsequently recognized by the forty Greeks who were later rescued by the Greek army, for they had being hiding in various places as caves, fields and other spots in the neighborhood of the town. At 10 o’clock exactly on the 12th of June [1919], when the looting was completed, Turkish soldiers and rebels, directed by officers of the Turkish army and gendarmerie put fire with inflammable materials to various points of the Greek quarter, houses and shops being thus consumed in the conflagration which lasted for two days. More than 60 Greeks, hiding in their houses, were burned to death and their charred bodies were found afterwards. The unfortunate people could not save themselves both on account of the fire and of the irregular soldiers who killed those who sought protection, after cruelly torturing them. The whole of the Greek quarter and market was consumed, excepting 70—80 houses at the northwestern part of Upper Nazli.

On June 13—16 of the same year, Turco-Cretan rebels and Turkish inhabitants of Nazli, speaking Greek and wearing the Greek military uniform went through the Greek quarter and called out to the hiding Christians to leave their houses, for the Greek army, they said, had entered Nazli and they were Greek soldiers. Those who attached faith to the deceiving shouts and left their hiding places, were seized and put to death with horrible tortures. Fifty-nine Greek workmen, working on the bridge of Ak-Tchai on the Meander and on the road to Boz-dogan were also carried away on June 12, and probably put to death.

After the events at Aidin [Aydın] (June 1919) a crowd of 7.000 Greeks had gathered at Nazli, coming from Aidin, Omourlou [Umurlu], Akdje [Akçe], Kiosk, and other towns of the Aidin district. The losses of the Greek population of that district up to the time of the Turks’ departure from Nazli may be stated as follows : (1) From June 17, 1919 to June 11, 1920 about 300 Greeks were put to death by Turkish soldiers and irregulars or by the Turkish authorities, wouing to suspicion about them; (2) From June 11 to 18, 1920, 38 men, women, and girls were killed, their bodies being recognized later; (3) 60 persons, mostly women and children, whose men were long ago murdered, were burned alive, and their charred remains were found and recognized; (4) 59 Greek workmen were carried away, probably thrown into the Meander; (5) 4 Greeks were tortured and murdered and their bodies were thrown into the Meander on the evening of the 12th of June by the brigand chief Dikouzoun Hassan Hussein with his 8 followers, unknown as yet; (6) 40 Greeks who remained at Nazli were found; (7) the remaining Greek inhabitants of Nazli were deported to Denizli, Davazon etc., and 20 of these, mostly women, were massacred on the road from Nazli to Kouyoudjak [Kuyucak].”[4]