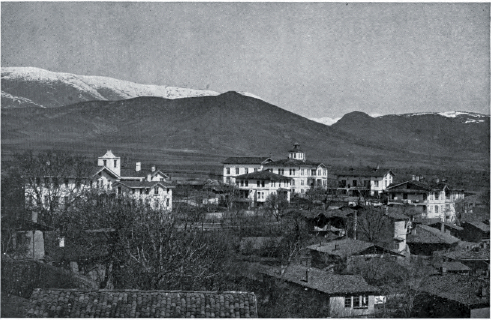

The administrative seat of the kaza was located between the Alis and Yeşilırmak (Grk.: Iris) rivers, 60 km north-west of Amasya, at the foot of the mountains, in a picturesque garden plain.

Toponym

The name of the city and the kaza of the same name was derived from the Persian title ‘Marsban’ (for district governor), or from Persian ‘mars’ (border) and Armenian ‘Van’ (‘city’), respectively.

Alternative or older toponyms were: Theodosopolis, Marsova, Marsvan, Merzipun, Mezifon, Merzifun, Mersivun, Yushet.

Historically, the settlement was known as the Pontic Phazemon (Grk: Φαζημὠν). In medieval Armenian sources the settlement is mentioned as Marzvan.[1]

Population

In 1800-1830 the town of Merzifon had 18,000 inhabitants, of which 8,000 were Armenians. At the end of the 19th century, according to Garegin Srvandztyan, there were 6,496 Armenians, 6,874 Turks, and 58 Greeks. In 1914, Merzifon had 35,000 inhabitants, of which 14,000 were Armenians.[2] However, Johannes Lepsius mentioned an overall pre-war population of just 22,000 in the town of Merzifon; of these, 12,000 were Armenians.[3] According to Raymond Kévorkian the Armenian pre-war population of the kaza was 10,666, residing in three localities and maintaining one monastery and eleven schools with an enrolment of 1,221 children[4]; the vast majority, 10,381 Armenians, lived in the administrative seat Merzifon. There were only two Armenian villages in the district (Yenice, pop. 140; Lic/Kotköy, pop. 145), “located near the monastery of the Holy Mother of God, which served as the seat of the bishop of the joint diocese of Amasia and Marzevan.”(5) According to other Armenian sources, the town of Merzifon had three churches, among them the Holy Mother of God (Surb Astvatsatsin, rebuilt 1835), where 50 manuscripts were kept.[6] The National Lyceum operated in Merzifon, furthermore the Surb Sahak and Hripsime schools and the Cultural Society of the Educational Union.

In the Middle Ages Merzifon was a center of Armenian literature. Mass media such as the periodicals Zepyur (1889), Arusyak (1889), Haykuni (1910-1912), Bogboj (1911-1914) and Nor Hayk’ (1910-1914) were published there.[7]

The Armenians of Merzifon were engaged in crafts (coppersmithing, weaving) and trade. The trade in cotton fabrics was widespread. The town had many shops and an abundant market.

Merzifon was home to one of the last communities of Armenian Zoroastrians – known as Arevordik (‘children of the sun’), who are believed to have been killed in the genocide between 1915–17. In the town of Merzifon, in the early 20th century, the Armenian quarter was known as “Arevordi”. Furthermore, a cemetery outside the town was known as “Arevordii grezman”, and an Armenian owner of a close by vineyard was named “Arewordean”, in other words, Armenian for “Arewordi-son”.[8]

Notable Armenians

Gradzuli: printer

Grigor Mazvanetsi (17th/18th centuries): Founder of the engraved art of Armenian printed books

Sedrak Gljchyan (1867-?): painter, artist

Aram Yeremyan (1898-1972): philologist

Zapel Mankasaryan (1880-?): opera singer

Greek Settlements

Μερζιφούντα – Merzifounta (Merzifon)

Γκελίνσινι – Gelinsini

Μαχμουτλού – Makhmoutlou (Mahmutlu)

Μπακίρτσαϊ Μαντέν – Bakirtsay (Bakirçay) Maden

Οσμάνογλου – Osmanoglou

Παγιά (ή Μπαγιάτ) – Pagia (or Bayiat)[9]

Arevordik – Children of the Sun

The direct heirs of the scattered and persecuted Paulicians in Armenia appear to be the T(h)ondraks (mid-9th to 11th century), named after their center, the village of Tondrak in the province of Turuberan, north of Lake Van, where the priest Smbat had gathered them. Initially persecuted only by the leadership of the Armenian Church, whose privileges they dared to challenge, the Tondraks were later increasingly oppressed by the Byzantines. Byzantium felt particularly challenged when it attempted to annex large parts of Armenia in the 1130s and was directly confronted with the Tondraks, whose movement now took on the character of national resistance.

With the crushing of the Tondrak movement, however, the ‘heretical’ resistance in Armenia was by no means broken. In the 11th and 12th century with the ‘Sun Children’ (Arevordik) in southern Armenia, Cilicia and Mesopotamia another heretical mass movement arose, in whose teachings pre-Christian autochthonous Armenian with Iranian-Masdaistic faith elements blended. As already the name says, the ‘Sun Children’ revived the ancient sun cult, whereby they equated Christ with the sun. They also worshipped the poplar tree and the lily. In 1170 they officially reconciled with the Armenian Church, but independent communities continued to exist until the end of the 19th century in northern Mesopotamia, especially around the city of Amid (Diyarbekir).

History

Archaeological evidence indicate settlement of this well-watered farmland since the stone age at least 5500 B.C. The first fortifications were built by the Hittites, who were pushed out around 1200 B.C. by invaders coming in from the nearby Black Sea. From 700 B.C. the fortifications were rebuilt by the Phrygians, who left a number of burial mounds and other architecture. From 600 B.C. the Phrygians were pushed out by more invasions from the east, this time Cimmerians from over the Caucasus mountains. Merzifon then became a trading post of the kings of Pontos, who ruled the Black Sea coast from their capital in Amasya.

Rome and Byzantium

The district of Amasya was destroyed during civil wars of the Romans and, including Merzifon, was restored by command of the emperor Hadrian. The city grew in importance under Roman rule as walls and fortifications were strengthened, and remained strong under Byzantine rule (following the division of the Roman empire in 395), although it was held briefly by Arab armies during the 8th century expansion of Islam.

Turks and Ottomans

Islam was finally established by the Danishmend lords in the 11th century and the Byzantines never regained control. The Danishmend were followed by Seljuk Turks, Ilkhan, and from 1393 onwards the Ottomans.

Merzifon remained an important city for the Ottomans, because of its proximity to Amasya (where Ottoman princes were raised and schooled for the throne). The Ottoman traveller and explorer Evliya Çelebi records a well-fortified trading city.

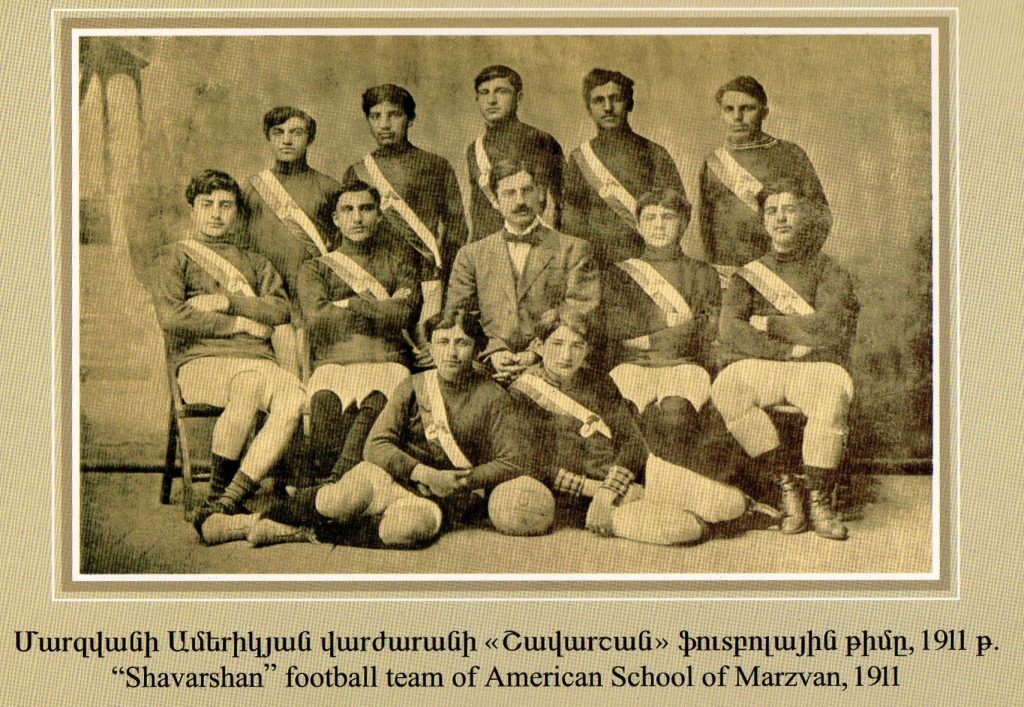

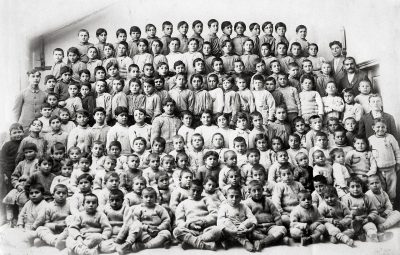

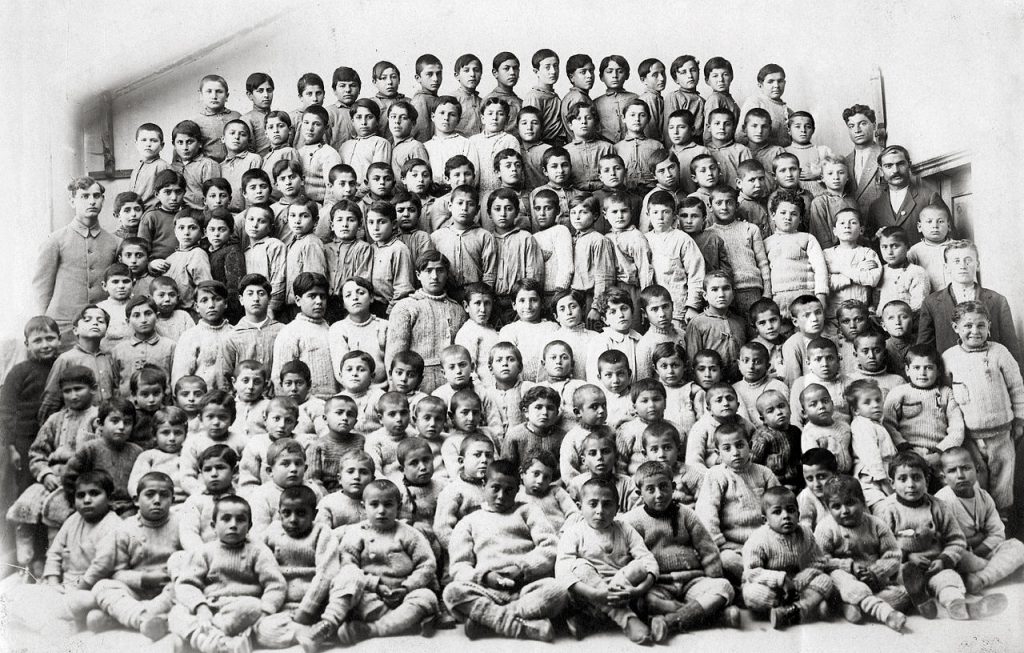

Merzifon became a center of European trading and missionary activity by the 19th century. American missionaries established a seminary in 1862. In 1886, a boarding school, Anatolia College in Merzifon was founded (and expanded to also serve girls in 1893). By 1914, the schools had over 200 boarding students, mostly ethnic Greeks and Armenians. The complex also had one of the largest hospitals in Asia Minor, and an orphanage housed 2000 children.

Turkish Republic

After the collapse of the Ottoman Empire at the end of the First World War, unrest continued. British troops deployed in formerly Ottoman lands to ensure the terms of surrender; some arrived in Merzifon in 1919 as American missionary George White returned and reopened the college and orphanage, as well as a new ‘baby house’ for displaced Armenian mothers and infants. However, the British troops soon withdrew and unrest continued in Merzifon.

Destruction

1915

In 1915, over 11,000 Armenians were deported from the city (which had approximately 30,000 inhabitants the previous year) in death marches; others were killed and their property confiscated and sold to Turkish insiders, supposedly to benefit the Ottoman war effort, as documented by missionary George E. White. He also estimated that 1,200 Armenians converted to Islam to evade deportations and save their lives. In addition, in 1915 several Greek men were murdered, while the women with their babies were compelled to follow and accompany the Ottoman troops. The women who were exhausted after the long marches were abandoned together with their babies on the roadside. Anatolia College in Merzifon was closed in 1921 and all remaining Christians were forced to leave.

On 15 March 1915, the authorities proceeded to arrest 17 Armenian men involved in politics and education in Merzifon and Amasya. They are interned in the medrese of Sifahdiye at Sivas. Three months later, on 15 June 1915, one thousand two hundred men arrested during the past several days were eliminated in several groups. The first, made up of 300 young people, was escorted to Elek Deresi near the village of Tenik on the route from Çorum, under the direct supervision of Faik Bey, the kaymakam, and Mahir Bey, the Commander of the Gendarmerie; they were stripped and hacked to death with axes. In the following days the other prisoners suffered the same fate.

Between 15-30 June 1915, Armenian males in Tokat, Amasya, Merzifon, Zile, Niksar, and Hereke (province of Sivas) were arrested and almost immediately executed in their respective regions.

On 21 June 1915 around 9,000 Armenians of Merzifon were set en route to the Syrian Desert via Hasançelebi, Fırıncılar, Suruc, and Arabbunar, and then Bab and Aleppo, where some 20 men and less than 100 women and children arrived.

On 10 and 12 August 1915 seventy-two Armenians, including a number of professors who had taken refuge in the Anatolia College, were questioned en route to Zile, where they had been escorted by gendarmes. The men were separated into one group at Yeni Han, bound together, and executed. On 12 August, police and gendarmes broke through the gates of Anatolia College and seized the 63 Armenian orphans of the American establishment.

On 26 August 1915 the American medical and hospital corps of Merzifon, comprised of 52 Armenians who mainly took care of the war-wounded, were arrested by of Governor Muammer, and eliminated.[10]

1921

Together with the remaining Armenians, the Greek Orthodox population of the kaza Merzifon was exposed to massacres and deportations during the years 1919-1921, in particular in late August 1921.

Upon his arrival in Merzifon with his irregulars on 13 July 1921, and “despite the objections of the local deputy governor, Feridunzade Osman Ağa (alias ‘Topal’ Osman) had all the men arrested and savagely murdered. Then he gathered the women and children in the building of the French Frères school, wanting to burn them alive; fortunately, they were saved due to intense protests on the part of the local Turkish authorities, and were sent—unclothed and unshod—to the small Greek town of Metallion-Sim twenty kilometres away, where they were kept for a few days”.[11]

“Following the Ankara wars, the inhabitants of Vezirkopru [Vezirköprü] and Sivas were led to an unknown destination and disposed of. The approximately 5,000 Greek residents of Merzifon and Havza shared the same fate; they were massacred on the same day and their property was seized. Since such actions had proved very profitable both for Ankara and the Chetes [irregulars], it was decided to intensify them; thus, starting from Amasya and covering the entire area between Amasya and Trebizond, they continued with the general massacres and deportations until the Greek element was completely wiped out.

1,280 of the most wealthy and outstanding Greek inhabitants of Yozgat, Merzifon, Havza, Vezirkopru and other places—bank managers, merchants and teachers included—were executed officially and their property confiscated. Only 15 of them were given life sentences and incarcerated in Merzifon prison.”[12]

The massacre in Merzifon of July 1921 lasted four days. Approximately 1,000 Greeks and Armenians were killed. Their corpses were later dumped and buried in pits in a Christian cemetery.[13]

On 27 August 1921, 1,230 Christians, mostly women and children, were deported from Merzifon, Amasya, Havza, Torpocuk, Iledig and villages of Samsun to Elâzığ and further to Bitlis or Van. On 30 August 1921, 1,650 Greek women and children from Merzifon and villages between there and Samsun were deported to Elâzığ, then Bitlis, followed by another convoy on the next day (31 August 1921) with 1,284 people from Merzifon, Havza, Amasya, Koppy, and Hadign, driven again to Elâzığ, then Bitlis. [14] Further deportations of men only from Merzifon to Sivas, Tokat, Erzurum and Gümüşmaden during 1919-1922 are also documented.

On 16 October 1921, the correspondent of The Times newspaper wrote:

“Reports from reliable witnesses of slaughter in Merzifon (an area about 60 miles inland from the Black Sea city of Samsun), which have reached Istanbul, demonstrate that, irrespective of their promises, the nationalistic government is either incompetent or unwilling to control the irregulars being used for suppression.

No Greek revolt, much less any Armenian movement, had occurred prior to these massacres; no such event was perceived. Some Greek teachers from the American College in Merzifon had been indicted a few months earlier, accused of maintaining connections with the Pontian movement, and the college closed. Some Americans, however, stayed there and associated themselves with the relief work of the American Aid Commission in the Near East.

In the last week of July, the local governor received a message from the infamous Osman Aga, informing him of his intention to visit the town with his irregulars. He responded, expressing hopes that there would be no incidents and then locked himself away. As soon as the irregulars arrived, they started to murder, rape and rob Greeks and Armenians. Most of the Christians who had not managed to escape to the American military camp were confined to three buildings: the French school, the police barracks, and the Red House. There were several women in the latter.

The irregulars invaded the Red House and raped most of the women, after they had robbed them. They set fire to the French school, but the people inside were saved by the intervention of some prominent locals. Of those in the barracks, many were killed. A refuge for widows, founded by the Americans, was attacked. Some of the women were killed and others were seized by the irregulars.

About 500 women and children were transferred to villages about 15 miles from Merzifon. Most of the elderly men of the town were killed. The irregulars tried very hard to locate the Armenians who had converted to Islam in 1915-1916 but were subsequently encouraged to return to Christianity when a British military base was established in Merzifon.

After four days in the town, the irregulars departed. The gendarmes and some armed villagers continued to plunder for another three or four days. The dead, amounting to some 1,200 out of a total Christian population of 2,000, were buried near the American camp. At least two of the people thrown into a trench and buried were still moving.”[15]

The Central Council of Pontus received eye-witness accounts of atrocities committed by Osman Ağa and published them in a report dated 17 October 1921, in which Merzifon was also mentioned:

“(…) At Merzifon, Osman Ağa and his companions, after having completely bereaved all the Christians, put fire to the Greek and Armenian quarters. The scenes which took place in the course of the fire were appalling. All the exits were barricaded and the unfortunate people trying to escape were either mercilessly killed or thrown back into the fire without distinction of whether they were women, children or old men. In the course of 5 hours, 1800 houses along with their inhabitants were burnt down. It was impossible to describe the orgies committed against virgins and children. While they were performing these cruelties, they shouted at their victims: ‘Where are the English, the Americans and your Christ to save you?’”[15]

Simeon Ananiades: An Innocent Greek Lad Hanged by the Kemalist Turks

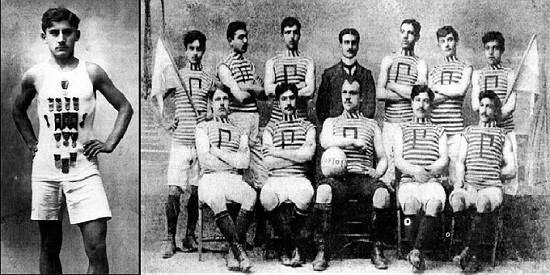

Simeon Ananiades (1902-1921) was born in Samsun in 1902 and was a student of Anatolia College at Merzifon in Ottoman Turkey, a college founded by Americans in 1887. After passing his entrance exam, he was admitted to the third year preparatory class of the college. He had an interest in English and literature and excelled in math and biology and often talked of becoming a physician. Overall, he was an A-plus student in all his subjects, a young man who was intelligent, handsome, eloquent, kind and co-operative. One of his goals in life was to break the World record in the 100 yards sprint. He was also a very loyal Ottoman subject.

Apart from its athletic clubs, Anatolia College also had literary societies, one of which was the Pontus Club. It met every Saturday night and many of the Greek students at Anatolia were members. On 12 February 1921, Kemalist general Jemil Jahid [Cemil Cahit Toydemir] accompanied by hundreds of soldiers entered Anatolia College and began searching for guns and ammunition. The building was left severely desecrated and not a single gun or bullet was found. The only thing found was a map in the president’s office of the historic region of Pontus during ancient and classical times (500 and 200 B.C.). All Greek books from the Pontus Club were subsequently confiscated on the grounds that the literary Pontus Club was a ‘revolutionary club‘.

Early on the morning of 13 February 1921, Ananiades and three other members of the Pontus Club Executive Committee along with Professor Theocharides, were summonsed into the room of College president Dr. George E. White and were arrested by Kemalist gendarmes. They were then sent to Amasya to face trial at the infamous Courts of Independence which often meant a certain death sentence without the prospect of a fair trial. Ananiades along with hundreds of other Greeks and Armenians were tortured for months before being hanged. According to eyewitness Mr. P. Ebeoghlou of Amasya, before Ananiades was hanged, he managed to shout out six words. “I am innocent. Ask Dr. White!”

The story of Simeon Ananiades and the Pontus Club are told in the publication titled 23 Years in Asia Minor.

Excerpted from: https://www.greek-genocide.net/index.php/overview/other/148-simeon-ananiades-1901-1921?highlight=WyJtZXJ6aWZvbiJd