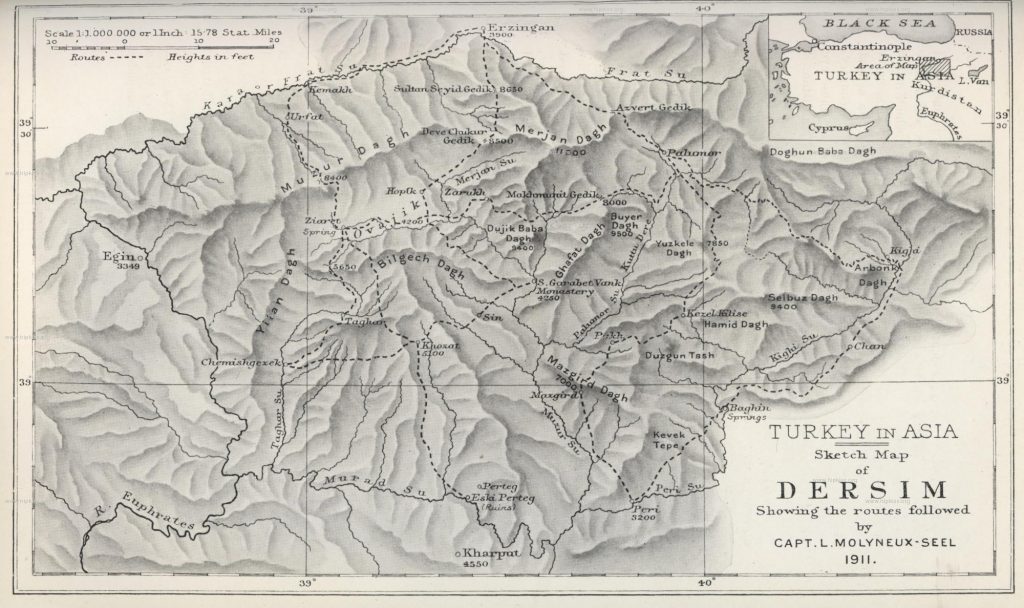

“The Dersim is a rather indefinitely defined region lying in the north from Harput, between the east and west branches of the Euphrates River. It does not include all of that area, but that part of it that is inhabited solely by Kurds in their native mountain districts. The plain around Erzingian [Erzincan], the Armenian region about Chemishgezek [Çemişgezek], and the somewhat more domesticated regions of Charsanjak [Çarsancak] are not ordinarily understood as included in the term, which is reserved for the home of the unruly Kurds.”

Quoted from: Henry H. Riggs: Days of Tragedy in Armenia: Personal Experiences in Harpuut, 1915-1917. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Gomidas Institute, 1997, p. 109

Administration

According to the map drawn by Vital Cuinet, the Ottoman sancak of Dersim comprised the nine kazas of Hozat (with the capital seat of same name), Çemişgezek (Arm.: Չմշկածագ – Čmškadzag), Çarsancak (Չարսանջակ – Charsanjak; previously Peri / Բերրի – Berri; today Akpazar), Medzkert (Mazgirt, Mazgird), Ovacık (also Zerenik or Pulur / Plur, from Arm. ‘blur’- ‘hill’), Kızılkilise (Nazımiye), Pertek (from Arm.: Բերդակ – ‚berdak‘ – ‚little fort‘; Western Armenian pronounciation ‘pert/ pertak’), Kuziçan (Kuzican, Pülümür), and Pah.

Dersim is historically divided into an eastern and a western part. East Dersim consisted of the Ottoman districts (kazas) of Hozat, Çemişgezek, Pertek, Ovacık and Kemah, while west Dersim consisted of the kazas of Medzkert (Mazgirt), Kiğı, Çarsancak (formerly Peri, now Akpazar), Kızılkilise (Nazımiye) and Kuziçan (Pülümür). Since 1847 or 1848, Dersim administratively formed the sancak of Dersim or Hozat with the administrative center of the same name. In 1867, the kazas of Çarsancak, Ovacık, Mazgirt and Kuziçan (Pülümür) were attached to the sancak Erzincan of Erzurum province. The remaining Dersim districts formed an independent province (vilayet) for almost ten years, from 1879 until 1888, when it was downgraded to the status of a sancak with the nine kazas of Çarsancak, Mazgird, Kızılkilise, Kuziçan, Ovacık, Hozat, Pertek, Çemişgezek and Pah and placed under the Province of Mamuret-ül-Aziz . In the following years, the number of kazas decreased to six.

In 1914, Pertek was the administrative seat of the sancak.

Toponym

The place-name Dersim translates as ‘Silver Gate’. In 1937 and 1938, it was genocidally subjugated by the Turkish Republic, colonized as well as renamed Tunceli (‘land of bronze’).

Population, Languages, Religions

In the early 20th century, the majority of Dersim’s inhabitants belonged to Iranian ethno-linguistic groups, speaking Zazaki and Kirmancki [Kırmanjki; Dımılki], which is also called Northern Kurdish. According to the Armenian historian Andranik (Western Armenian: Antranik), who visited Dersim in 1888 and 1895, the ethnic group of the Dımıli, who call themselves Kırmanc, Kird or Zazas, form the descendants of the Daylamites of Parthian origin; their original settlement area was on the southern coast of the Caspian Sea and in western Khorasan. According to other experts, the ethnonym Zaza is a collective term for an ethnically heterogeneous population group. Accordingly, the aforementioned self-designations as Zaza, Dımıli, or Kırmanc are used in different ways.

Although the majority of Dersim’s population spoke Iranian languages, namely Kırmancki, also called Zazaki, or Dimilkî as well as Kurdish, the Turkish state power has made Turkish the sole official language. The number of Zazas or Dımıli is estimated at 3-4 million. However, only two to three million still speak their native language, Dımılki or Zazaki, which belongs to the northwestern Iranian language group. Zazaki has the greatest affinity with the extinct Parthian language. UNESCO lists it as one of a total of 18 endangered languages on the territory of present-day Turkey.

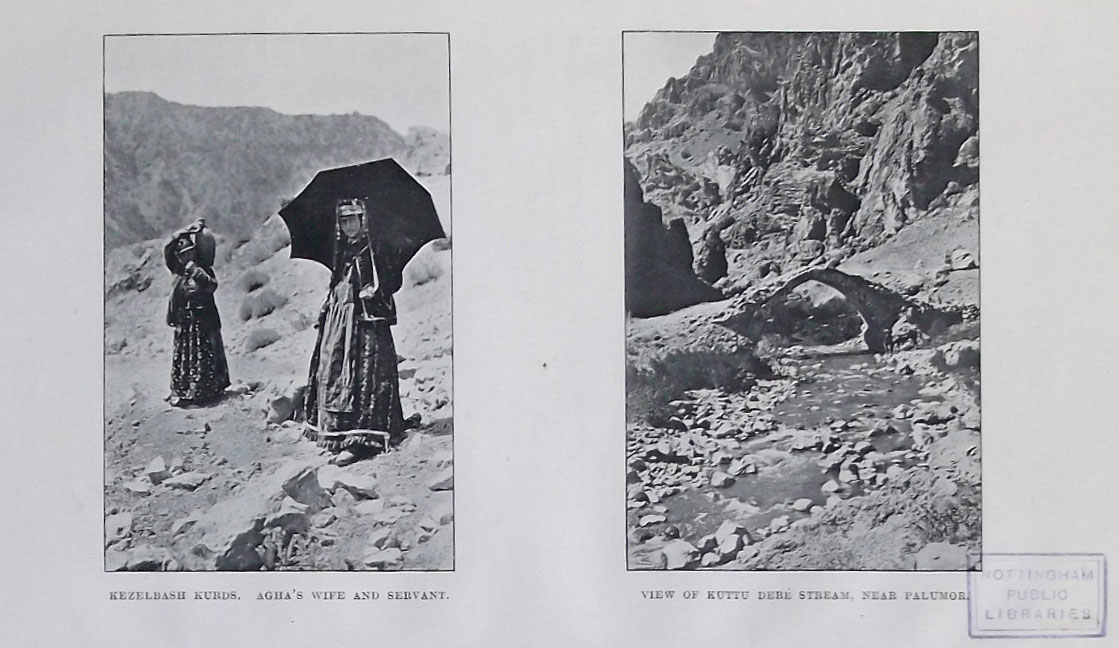

In the early 20th century, Europeans and Ottomans consistently referred to Dersim’s non-Turkish population as Kurds. Today, many Zazaki / Kırmancki /Dımılki speakers consider themselves a distinct ethnos. Nearly three-quarters – 70 percent – of the Dersim-born population now live outside their homeland, either in western Turkey, or in European countries, predominantly Germany.

In religious terms, the Dımıli in northern Dersim belong to the Alevi or Kızılbash religious community; in the southern half, Dımıli belong to Sunni Islam, as do Kurds and Turks. The Alevi Dımıli, on the other hand, refuse to be classified as Muslims. They emphasize the independence of their orally transmitted syncretic faith, which contains elements of natural religion, Zoroastrianism and even shamanism. Armenian Christianity proved equally powerful: Dersim Armenians and Alevi Dımıli alike venerated the monastery of St. John the Baptist (Armenian: Surb Karapet, Western Armenian: Surp Garabed) in Halvori. “Parallel to the worship of Saint Serge, whose feast day was preceded every year by seven days of fasting, or that of the Twelve Apostles, the Holy Cross, and the Hake sun (the feast of the ‘red eggs’)- that is, Easter, which the Kızılbash celebrated in common with the Armenians – the followers of this syncretic religion turned toward the east when they prayed and went on pilgrimages to monasteries, which they protected against all incursions as if they were part of their own heritage.” (1)

The 162 Armenian churches that were once located on the territory of Dersim testify to the former presence and cultural activity of the regional Armenian population.

History

The central Anatolian region of Dersim is located in eastern modern Turkey, with the cities of Bingöl, Elazığ, and Erzincan on its borders. In late Ottoman times, Dersim formed a sancak, a district, within the province of Mamuret ül-Aziz.

Since the 16th century, the Alevi population of Dersim has been known as Kizilbashis, which means ‘red heads’. This is the Turkish loan translation of the Iranian term ‘Surh-i Ser’ and refers to the red headgear worn by men since the times of Shah (Sheykh) Haydar Safavi by the followers of the Iranian Safavid dynasty. Nevertheless, one should not confuse the faith of the Dersim with that of the Shiites.

The Kızılbashis of Dersim do not practice Islamic prayer (‘namaz’), do not attend mosques, do not make pilgrimages to Mecca, and do not fast during the month of Ramadan. Neither do they believe in the Koran. Instead, their faith contains pre-Islamic, and in some cases, natural-religious elements. The following sayings of the Kızılbashis refer to humanity as the basis of their culture: “We look at the 72 nations through the same eyes.” “Whatever you desire, seek it within yourself, not in Mecca or Jerusalem.” “Our Kaaba is Man.” “The wisest book to read is a human being.”

Tertelê: ‘The Day The World Ended’

Because of such and other beliefs, Kızılbashis were persecuted as heretics. Herein also lies the religious origin of the Dersim Question. During the so-called modernization era, the pressure intensified as Turkish nationalism grew in the nation-building process. Similar to the Soviet Union, natural and tribal peoples were considered pre-modern or backward, from which Kemalist Turkey derived the justification for forced modernization, just as the Soviet Union did at the same time.

Dersim’s non-Muslim and non-Turkish identity was not acceptable to Islamists or Turkey’s chauvinist rulers. A third reason for the growing unacceptance and persecution was the fact that Dersim became a refuge for Armenians during World War I, during the Ottoman genocide. Many managed to flee from Dersim behind the Russian front line. Those who did not succeed assimilated into the Alevi population. Kemalist Turkey has never forgiven this.

Dersim was repeatedly the victim of punitive expeditions. In his report, Turkish General Ömer Halis Bıyıktay admitted that “by 1930, the Dersimis had suffered at least 40 massacres.” Shortly after the Turkish military’s punitive expedition of 1937/38 against Dersim, Turkish journalist Latif Erenel wrote in his newspaper Tan: “According to what I have learned in Dersim, 108 military operations have taken place against the Munzur Mountains. But in none of these campaigns has the army been able to advance far into the countryside.”

According to Şükrü Kaya, in 1915 administrator of the concentration camps of Armenian deportees located in Syria and Minister of Interior from 1927 to 1938, “11 punitive military expeditions took place against Dersim between 1876 and 1935.” According to the reports of the First Inspector General Dr. İbrahim Tali Öngören written between 1928 to 1933, there was not a single tribe in Dersim that had not been “punished” during the period of the last 20 to 30 years, that is, between 1908 and 1933.

Under the impact of Italian fascism and German Nazism, the Turkish Republic of the 1930s became an openly fascist state, with Kemalism as its Turkish variant. This racist regime committed genocide in Dersim in 1937-38, after a ten-year period of planning and preparation.

Already the fact that none of the Turkish cease-fire offers or even promises of amnesty or compensation were complied with speaks of the determination for complete annihilation. The elderly tribal leader Pir Sey(it; Seyid) Riza (*1862 in Derê Arí, or Lirtik/Ovacık County; †1937), who was quickly denounced as the leader of the “uprising”, was also deceived by this.

At the onset of winter, he turned himself in to Erzincan with 50 loyal followers, but was promptly arrested and hanged in Elazığ on 16 November (according to other accounts: 18) 1937, along with eleven others sentenced to death, including his son Resik Hüseyin. Ihsan Sabri Çaglayangi, who as a young official had organized the summary trial of Sey Riza and his co-defendants and later rose to become Turkey’s foreign minister, passed down in his memoirs Sey Riza’s last words before he put the noose around his own neck: “”We are the sons of Karbala. We are blameless. It is shameful. It is cruel. It is murder!”(2)

The campaign of the Turkish military ended in the last week of August 1938. The head of the government at that time, Celal Bayar, confessed in his memoirs that during the bloodiest phase, i. e. between 23 and 31 August 1938, he himself, Mustafa Kemal and the commander-in-chief, Marshal Fevzi Çakmak, jointly led the military operations in Dersim and that it was Mustafa Kemal, the founding father of the republic and ‘Father of all Turks’, who gave the order to kill. Audio recordings of a report from 1986 with contemporary witness Ihsan Sabri Çağlayangil are said to prove the use of poison gas by the army. Literally, it states: “They had taken refuge in caves. The army used poison gas. Through the entrance of the cave. They poisoned them like mice. They slaughtered those Dersim Kurds (aged) from seven to seventy. It became a bloody operation.” (3)

Air strikes played a special role in this. They were flown by Mustafa Kemal’s adopted daughter, Sabiha Gökçen, the world’s first female fighter pilot. Kemal had adopted Gökçen, who was born in Bursa in 1913, at the age of twelve. When the Armenian journalist Hrant Dink revealed in 2004 that Gökçen was of Armenian descent, an orphan of the genocide, it triggered a storm of indignation in Turkey. The use of a female pilot of Armenian descent in the Turkish military’s genocidal war against a non-Turkish region and its heterodox, predominantly Iranian-speaking population would be a particularly sarcastic episode in the sarcasm-rich history of the Republic of Turkey. In any case, the Kemalist genocide in Dersim proves to be a continuation of the Young Turks’ genocide against Christians. In both cases, the same methods were used. Since they were never dealt with legally and, above all, politically, they were and are apparently considered tried and tested instruments of domestic policy.

The descendants of the up to 70,000 Alevi victims in Dersim commemorate the genocide of 1937/38 on 4 May (1938) as ‘the day when the world ended’ (Tertelê).

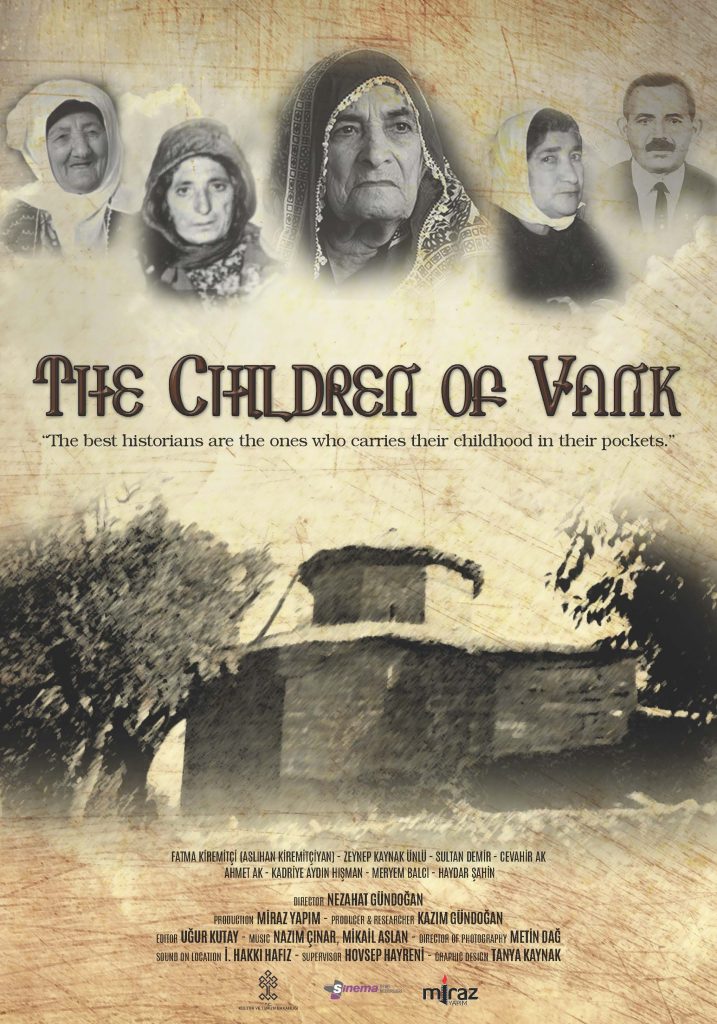

Nezahat Gündoğan: The Missing Girls of Dersim

Under the pretext of crushing a rebellion, the Turkish state carried out a great massacre in Dersim (Tunceli) in 1937-38. Tens of thousands were killed, without distinction between men, women or children. Thousands of families were forcibly resettled in the western Turkish provinces. From then on, both these massacres and the history of Dersim were taboo subjects in Turkey. In official historiography, these events were referred to either as the “Kurdish uprising” or the “feudal uprising”. There were independent researchers who investigated the events in Dersim. But even in works that differed from the official historiography, the victims of Dersim were portrayed as losses that were supposedly inevitable in the course of the crushing of the “Kurdish uprising”. Such an assessment was made even when the events were classified as massacres. Although we have learned much more about the fate of the people of Dersim who were murdered and forcibly resettled during this military intervention thanks to alternative research in recent years, the fate of the girls who survived the massacres and were taken away by officers remained unknown. Together with Kazım Gündoğan, we uncovered during our field research that girls from Dersim were distributed to members of the military and civilian bureaucracy. The aim of this measure was to assimilate the Alevi Kurdish, Zaza and Armenian girls to the Turkish Islamic culture. Based on our research work from 2009, which we called The Missing Girls of Dersim, we made the fate of these girls public and also put the fact that the events in Dersim in 1937-38 were massacres back on the agenda.

Dersim in State Discourse

At the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, Dersim was a region inhabited by different ethnic groups, such as Armenians, Kurds, Zaza and Turkmen, as well as different religions, with the Alevi population group dominating. Precisely because the majority of the population of Dersim did not belong to Sunni Islam, Dersim remained a marginalized and disadvantaged region within the Sunni-dominated Ottoman state and also during the violent process of the emergence of the Turkish nation-state.

The desire to bring the region and its population groups under control, which had been present since the beginning of the Ottoman era, became mixed with nationalist ideology after the establishment of the Turkish Republic, so that the state policy of assimilation was applied even more systematically and rigorously. Thus, starting in 1926, the Turkish government commissioned military and civilian bureaucrats to prepare reports on Dersim. Almost all of these reports recommended that the population of Dersim be ‘disarmed’, that the tribal leaders or disobedient tribes be forcibly resettled in the western Turkish provinces, that the area thus depopulated be Turkified by settling Turkish populations and by special educational measures for the remaining non-Turkish population, and that the nomadic segments of the population be settled and thus captured. All this was to be implemented in stages.

The reports are followed by a series of legal measures. The 1934 Settlement Law paved the way for deportations from the region. By law, Dersim was renamed Tunceli in 1935. Tunceli province was given a special military administration. The office of the governor, the military commander and the local administration were united in one authority, the so-called ‘Fourth Supervisory Authority’. The early Turkish republic was characterized by an authoritarian one-party system that relied exclusively on Turkish ethnicity from its inception and carried out military and administrative operations in Dersim that were referred to as ‘chastisement and deportation measures.’

The extent of the measures was outlined by the Council of Ministers on 4 May 1937: If one is content with merely offensive action, the pockets of resistance will persist. For this reason, it is considered necessary to definitively neutralize those who have used and are using weapons on the ground, to completely destroy their villages and to remove their families. In 1937, the then Prime Minister Ismet Inönü declared an end to military action after the massacres in the region. Under the government of Celal Bayar, who was appointed prime minister by Atatürk, who considered this first military action insufficient, a second and larger military offensive was carried out in 1938, this time reaching the scale of genocide.

Approximately 40,000 soldiers participated in the operation. The air and land forces used heavy weapons. Villages were bombed, torched, villagers rounded up and shot, pushed off cliffs or set on fire and murdered. Poison gas was used against women, children and men hiding in caves. The exact number of those killed and deported from Dersim is not known. However, in 2011, then-Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan stated that according to official documents, 13,806 people were killed and 11,683 people were forcibly relocated to western Turkey in 1937-1938. According to our research, the number of murdered people is two to three times higher than officially stated and the number of deportees is about 20,000.

Excerpted and translated from: http://www.aga-online.org/event/attachments/Nezahat%20Guendogan_Die%20verschwundenen%20Maedchen%20von%20Dersim_Vortrag_rev_red_at%20NG_Final.pdf

Armenians in Dersim

Dersim has a special significance in Armenian history as a place of refuge. Between 15,000[4] and 20,000[5] Armenian deportees from the western districts of the sancak of Erzincan, the plain auf Harput and other places probably owed their lives to the intervention of Alevi Dersimis, even if their help, in particular at the beginning of the deportation, was not always disinterested; many Dersimis allowed themselves to be paid handsomely for their help in escaping[6], especially since the presence of numerous refugees in Dersim triggered a famine.(7)

Until the First World War, 16,657 Armenians lived in this region(8). The ethnic composition of Dersim dates back to the 10th-12th centuries, when Iranian ethnic groups migrated here, the ancestors of today’s Dimilis or the Zazas, as well as Kurds. Under the rule of the rival Turkmen tribes of the Ak and Kara Koyunlu, ethnic groups of Turkic origin also immigrated from the late 14th century. Centuries of struggles for supremacy and religion between the Koyunlu, the Ottomans and Safavid Iran, and between followers of the Shia or Alevism and Sunni Islam brought suffering and persecution to all population groups, but especially to members of minorities.

Until the 1870s, Dersim was a semi-autonomous province of the Ottoman Empire, consisting of a plain and a forested mountainous area almost 2,000 meters high. While the plain increasingly came under the control of the Ottoman state in the 19th century, the inhabitants of the almost inaccessible mountainous area were able to maintain their independence for a longer period of time. From non-Armenian sources it is evident that Dersim became a place of refuge for Armenians from Bingöl, from Sebastia or Sivas, from Yersnka or Erzincan, from Kharberd or Harput from the 17th century at the latest. Those who wanted or needed to escape Ottoman pressure fled there, and some of the Christian Armenian refugees also converted to Alevism. During World War I, Dersim Alevis saved the lives of tens of thousands of Armenians, most of whom were able to flee to Eastern Armenia and Russian, later Soviet, territory. The remainder, however, stayed in Dersim and assimilated into the majority population.

The Dersim society was a tribal society to which the Armenian minority partially adapted. “Among the 40 tribes in Dersim, two – the Mirakian and the Der Ovantsik tribes – were Armenians. The Mirakians, whose territory lay near Dujik, Çukur, Ekez, and Torud, could mobilize 3,000 fighters. Earning their living almost exclusively from sheep-raising, as well as rugmaking and kilim-making, these mountaineers were partially liquidated in 1915, although a minority of them survived in Dersim.”[9]

The positive role that the Dersim tribes had played for Armenians before and during World War I sometimes makes one forget that in Dersim, too, Armenians had to suffer under the arbitrariness of semi-autonomous regional tribal leaders without the Ottoman state intervening to protect its Christian subjects. In the kaza Çarsancak (now Akpazar, formerly Peri between Harput and Tunceli), for example, local ‘Kurdish groups’ frequently confiscated Armenian land holdings. This triggered the complaint of the affected peasants against local derebeys (‘valley lords’) to the Ottoman government in 1865. The Armenian complainants also complained that the local derebeys demanded high taxes from them and forced them to take out high-interest loans to cover their debts. In case of refusal, the Kurds would take the Armenians’ land in debt bondage. The complainants demanded that seven of the derebeys be tried. The Sublime Porte then set up a commission of inquiry, but it concluded that the derebeys had already owned the Armenians’ land for a long period of time; from this ‘customary right’ they deduced that the peasants in question were merely tenants of the Kurds on the land in question.[10]

Belonging to Alevism and to the non-Kurdish language groups in Dersim seems to have been the criterion for determining whether those concerned participated in the massacres of the Kurdish Hamidiye units in 1895/6. A number of the Alevi-Kızılbash tribes, which were considered the ‘Kurds’ of Dersim, did not take part in the massacres of Armenians, which were organized by the Sunni-Kurdish Hamidiye cavalry units in the 1890s.[11]

Henry H. Riggs: The Underground Railway to the Dersim

“It was during this period [of the Great War] that the hunted Armenians began to flee into the Dersim. To those who knew of the depredations of the Dersim Kurds in the massacres of 1895, this sounds like a strange situation, for then the Kurds were the persecutors of the Armenians. That was, however, as it were, strictly a matter of business, as the Kurds in 1895 were invited to come and plunder the Armenians, and the killing at that time was merely incidental to getting the loot, which forms so large a part of a well-regulated Kurd’s income. In 1915, however, there was no loot to be had, for the government took care of that. And when it came to dealing with a defenseless Armenian fugitive, the instinct of the noble savage is to save rather than wantonly to destroy this neighbor against whom he has no grudge.

Furthermore, the Kurds of the Dersim have much in common with the Armenians – much more, in fact, than with the Turks. It is the opinion of many of the Kurds that they and the Armenians had a common ancestry. Whether or not this represents any broad ethnic fact, it is certainly true that the Kurds in the Dersim have many incidental reasons to believe it. The names of many of their villages are Armenian, and some of the tribes have names which sound like Armenian surnames. In their moral idea they are on a level much nearer to the Armenians than to the Turks. And in religion, though they bear the name of Mohammed, there is remarkably little in their religion that is Moslem in fact. (…)

It thus transpired that when the Armenians found themselves hunted to death by the Turkish government, those who were where they could do so fled for refuge to the Dersim. Naturally, the Kurds took often advantage of the situation to extort heavy pay from those who could pay for this protection. But in other cases, and especially where the fugitives were penniless, the Kurds not only protected them without compensation, but even shared their own meager living with those thus thrust upon them as guests or neighbors. Through the terrible winter of 1915-16 there was great want and suffering among these people, but the impulsive bigheartedness of many a rough Kurd meant life and hope to the Armenians among them.

The Armenians, once in the Dersim and under the protection of the Kurds, were, for the time being, safe from the Turkish government. For though the Turks had their representatives among the Kurdish villages, those representatives, as has already been intimated, were obliged to wink at many things that they did not approve, and so long as the Armenians kept out of sight when gendarmes were around, the Turkish officers would not dare to invade Kurdish homes to find them. The Armenians were thus kept in safety until the time came, with the advance of the Russians in summer 1916, when, with the help of the Kurds, they could pass over into the territory on the north side of the Dersim which the Russians occupied, and so to safety.

For the Armenians in the region of Harpoot [Harput, Elazığ] this way of escape was not, at first, available, because the Euphrates River forms an effective barrier. The ferries over that river are all guarded, especially in wartime, and for an Armenian to escape over the river into the Dersim was extreme dangerous if not actually impossible. At first, this obstacle effectually prevented any of the Harpoot Armenians from going to the Kurds, and it was not until after the first wholesale deportations, that that underground railway to the Dersim began its operations. This was nothing more or less than an arrangement between the Kurds from Dersim and the guards along the river, by which the latter relaxed their vigilance, while the Kurds smuggled the Armenians across the Euphrates. This was done first with the greatest secrecy, and with the payment of large bribes, the Armenians being dressed as Kurds, and going over by ones and twos. The first Armenians who went paid as much as $132 apiece, of which a considerable proportion was supposed to go to the Turkish guards and officials. How much of this went to those higher up I am not in a position to say. It was, however, a striking circumstance that so long as Sabit Bey, himself a native of the Dersim, remained in office as Vali [governor of the province] in spite of the fact that he had been most relentless in his persecution and extermination of the Armenians, the underground railway to Dersim was permitted to operate with ever-increasing openness and ease, but when he was removed to another post, all operations in this line were instantly and effectively stopped.

After the first secret and timorous trials were made, the Kurds and the Armenians both took courage and the business grew apace. With intervals of spasmodic vigilance on the part of the gendarmes, the traffic went on in increasing volumes and at decreasing expense. Those who had paid such large sums at first later regretted that they had not waited till the price dropped, as it did in course of time, to five dollars per person – and later on some were taken free, when the Kurds were convinced that they were actually penniless. After the occupation of Erzingian by the Russians, the Armenians of Erzingian made some sort of an arrangement with the Kurds by which all refugees from that city should be transported free, with the result that practically all such left Harpoot and returned to their native city. (…)

In all the history of the period of which I am writing, from the summer of 1915 to the spring of 1917, the Kurds from the Dersim were active and faithful in their effort to get the Armenians away into Russia.”

Excerpted from: Henry H. Riggs: Days of Tragedy in Armenia: Personal Experiences in Harpoot, 1915-1917. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Gomidas Institute, 1997, p. 111-113

Annika Törne: “On the grounds where they will walk in a hundred years’ time” – Struggling with the heritage of violent past in post-genocidal Tunceli

Conclusion

“Alternative heritage production in Turkey evolves in the discursive field span between Armenian Genocide denial and its legitimization, produced as two complementary elements.

In contrast, the specific historical and religious peculiarities of Dersim are, despite ongoing destruction, testified still today by Armenian Apostolic and Syriac Orthodox religious architecture and natural pilgrimage sites. Taking this regional distinctive heritage into consideration, it becomes obvious that the dominant exclusionary discourse on non-Muslim non-Turkish cultural heritage has particularly far-reaching and exhaustive consequences in Tunceli, former Dersim province in Turkey.

In order to scrutinize recent alternative heritage production, this study outlined the genealogy of the discursive formation of the Turkish state-led cultural heritage production in Tunceli. This reconstruction has shown that heritage production in post-genocidal Tunceli in archaeological and historical sites puts emphasis on an essentialist representation of Turkish Sunni-Muslim culture. In the discourse-defining Keban rescue project, heritage actors legitimated the exclusionary discourse by ostentatiously pointing at the inaccessibility of knowledge and the impossibility to mobilize resources in favour of restoring non-Muslim, non-Turkish cultural heritage in Tunceli. Turkish state authorities, by taking no measures against violations of non-Muslim cultural heritage, consolidate the legitimacy of acts of pillaging and destruction. As a consequence of the discourse of disregard, Armenian and Syriac heritage is not deemed worthy to be preserved, unless it promises future economic advantages through tourism. Thus, the Turkish post-genocidal society implicitly underlines the legitimacy of the annihilation of the Armenian victims in the Genocide.

The assumption that in recent years, as a consequence of the AKP government’s opening politics, the social framework of action for contested heritage production has changed, proves to be misleading. By means of two apologetic statements on the violent transformation process of Turkish nation state building issued by Turkish Prime Minister Erdoğan, the discourses on the events of 1915 and on the Dersim massacres have been transferred into the realm of civil society that continues the Armenian Genocide’s denial by recognizing it. Recent heritage actions related to Armenian churches, by presenting them as mere tourist attractions exploitable for the market, decontextualize the heritage. The existence and vital problems of Armenian community life inside Turkey is glossed over by externalizing Armenian cultural life into the Diaspora. Consequently, the imagined target audience consists in Armenians, as well as other foreign tourists, who only visit Turkey. Local heritage actors, also including descendants of Armenian survivors, broadly conform to the hegemonic discourse of denial by constructing the audience as alienated from Armenian Christian religious identity, and as undistinguishable from Alevi-Kızılbaş identity.

Furthermore, this study has shown that recent commemorative actions emerging among Tunceli communities engage in the representation of contested memories of the heritage of violent pasts in public space at the sites of massacres. By doing so occasionally, they voice the silenced memories of the Armenian Genocide as a strategy to strengthen their own claims for recognition of the Turkish state’s violent crimes from 1936 to 1938 as genocide. Meanwhile they adhere to the official discourse in the following crucial aspect: the argumentation pattern from the denialist discourse constructing the victim-perpetrator-equalization is met by drawing on the collective identity constructed as a victim group of Armenians and Alevis alike. Thus, recent heritage actors continue to conceal their responsibilities in the Armenian Genocide in 1915 by instead drawing attention to the massacres in 1938. In conclusion, it can be stated that recent efforts of civil society actors in Tunceli, striving for memorialization of the 1938 massacres, even if drawing on the genocide concept as a strategy of empowerment, continue to exclude the history of the Armenian Genocide and to reject responsibility. As a consequence, these 1938 commemorations and memorialization projects ultimately fail to counter the dominant denialist discourse.

The potential of the discourse on heritage to include the diversity of Anatolian heritage remains dependant on whether the preservation of non-Muslim heritage is acknowledged as a restitution of a traditional religious site, one that can be made use of by religious groups accepted as an integral part of Turkey. In this way the widespread conception in Turkish post-genocidal society of the legitimacy of the Armenian Genocide could be challenged.”

Quoted from: “european journal of Turkish studies”, 20/2015, https://doi.org/10.4000/ejts.5099