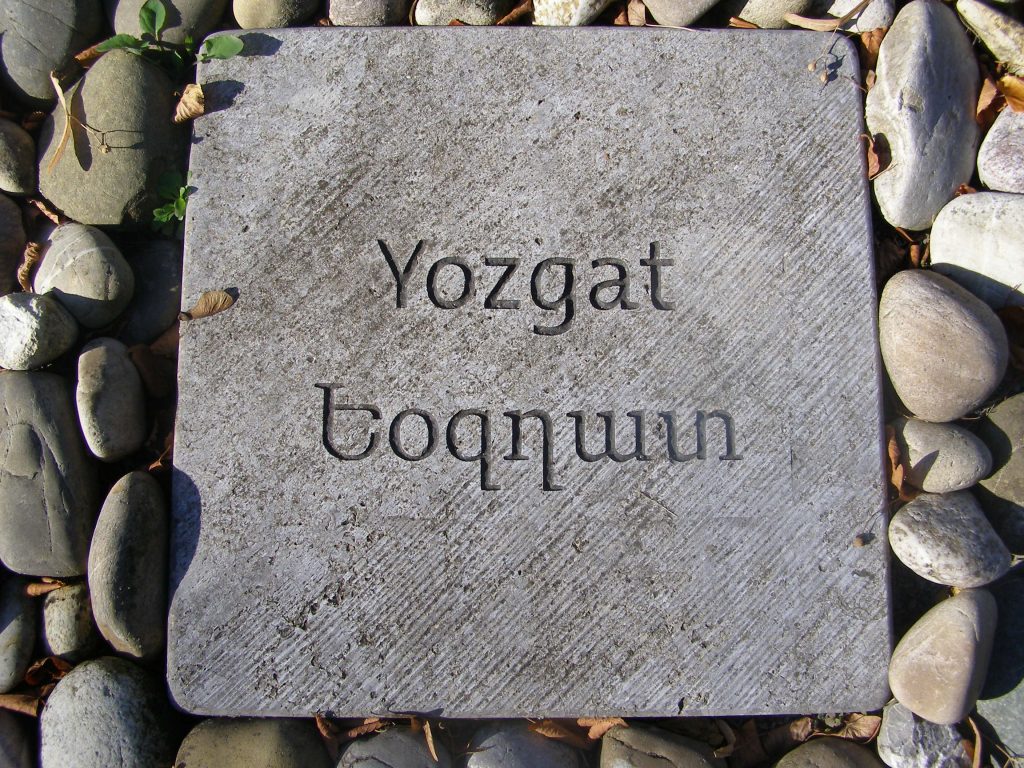

“At an altitude of 1,500 meters and furrowed by valleys, the sancak of Yozgat was famous for the fertility of its land.”[1]

Toponym

The old name of the town Yozgat (also called Yuzgat) is Bozok.

Administration

At around 1911, Yozgat was the chief town of a sancak of the same name in the Ankara Vilayet.

Population

“The sancak of Yozgat has 29,000 Gregorian [Armenian Apostolic], 1,500 Catholic and 500 Protestant Armenians in addition to 243,000 Mohammedans.”[2]

The Armenian population of the sancak Yozgat, “much more rural than elsewhere in the vilayet [of Ankara] lived in nearly 50 villages concentrated in the kazas in the southern part of sancak, in Yozgat, Boğazlian [Boğazlıyan], and the environs. This cluster of villages was simply the northern continuation of the Armenian-inhabited areas in Cappadokia. Armenians were also scattered, however, in the principal towns of certain other kazas, including Çorum, Süngürlü, and Akmağden. The total Armenian population of the sancak, according to local Armenian sources, was 58.611 in 1914, whereas the Ottoman census of the same year put the figure at only 36,652.”[3]

Settlements inhabited by Greeks in the Yozgat sancak:

Γιοασγάτη – Yozgati

Καριπλέρ – Karipler

Κωτσόγλου (ή Πέλκαβακ) – Kotsoglou (or Pelkavak)

Ποϊμούλ – Poymoul

Πουαλάν – Poualan

Τσαλουχλού (ή Τερέκιοϊ) – Tsaloukhlou (or Tereköy)(4)

History

The area was inhabited already in the Neolithic period. It was probably, at least in the north, Hattic, then belonged to the Hittite Empire. In 1398 it was taken by the Ottomans. After a brief annexation by the troops of Timur Lenk, the region has belonged definitively to the Ottoman Empire since 1408.

Destruction

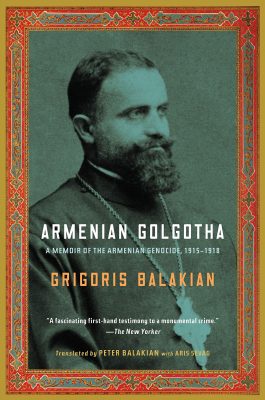

Grigoris Balakian: From Yozgat to Boghazliyan: The Skulls

“(…) we are now proceeding along the bloodstained roads from Yozgat to Boghazliyan [Boğazlıyan], from which not a single caravan before us had emerged alive. And Turkish peasants we met gave us shocking accounts of the massacres, without regard to sex or age, of the Armenians of Yozgat and the vicinity.

We had no time to think; we had to march. The interior minister and chief executioner, Talaat, had given orders by telegram throughout the disintegrating Ottoman Empire, even as far as the most remote villages, to take the Armenians outside the cities and towns, into the mountains and valleys, and mercilessly massacre them. He had also ordered that the remaining old women and children be marched along routes deliberately made longer, then annihilated by being left in the deserts of Der Zor without bread, water, or even a final resting place.

More than one million Armenian city dwellers and peasants were savagely slaughtered and made to choke quietly on their own blood. Tens of thousands of Armenian males, lashed together with string or rope, were mercilessly butchered along all roads of Asia Minor, or massacred with axes, like tree branches being pruned. The executioners were deaf to the crying and weeping of these wretched victims, even to their pleas to shoot them, so that they might escape torment: the order had come from on high, and the jihad against the Armenians truly had been proclaimed. Yes, it was necessary to mercilessly slaughter them until no single Armenian was left within the confines of the Ottoman Empire. The order for this wholesale massacre was executed with exceptional ferocity throughout the district of Yozgat because of Atif, the vice-governor of Ankara.

In July 1915 the governor of the Yozgat region had been unwilling to execute the order to massacre the Armenians, and was quickly dismissed; Mehmet Kemal, the kaymakam of Boghazliyan, was temporarily made vice governor. Barely had he assumed his post when he ordered the massacre of 42,000 Armenians throughout the Yozgat region. The order was carried out at a monstrous pace and included the sickling infants (…).

On our second day along the Yozgat-Boghazliyan route, we saw, in the fields on both sides of the road, the first decomposed human skeletons and even more skulls; long hair was still attached to them, leaving no doubt that they belong to females.”

Excerpted from: Balakian, Grigoris: Armenian Golgotha: A Memoir of the Armenian Genocide, 1915-1918. Translated by Peter Balakian with Aris Sevag. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2009, p. 135 f.

The Yozgat Trial: 5 February – 8 April 1919

The extirpation of the Armenian population of that sancak of Yozgat gave rise to the first trial conducted by the Istanbul court-martial, the proceedings of which run from 5 February to 8 April 1919. The government commission of inquiry headed by Hasan Mazhar was able to complete its pretrial investigation in short order, gathering initial proof and testimony from civilian and military officials as well as surviving victims and transmitting them to the court-martial. As often happened in the case of secondary trials, the court records of the 18 sessions of the Yozgat trial was not published in the Takvim-ı Vakayi, only the verdict handed down by the court-martial on 8 April 1919 appeared there. Istanbul newspapers, however, published, either wholly or in part, the exhibits and documents presented before the court.

“The defendants were charged with persecuting Armenians in Yozgat. Sixty-two further trials followed. In one, CUP Central Committee members and Special Organization officials were tried. In two others, cabinet ministers and CUP responsible secretaries and delegates appeared in the dock. But the courts, especially those in the vilayets, handed down few guilty verdicts. (…) The Turks had initially agreed to hold the trials in the hope of softening Allied punishment of Turkey itself. But within months they stopped the proceedings. In Paris the Allies had ruled that the Turkish people were ‘guilty of murdering Armenians without justification.’ But the Turkish authorities, both in Constantinople and Ankara, rejected the notion of collective guilt. The first postwar grand vizier, Ahmet Izzet Pasha, a Talât appointee, during his three weeks in office destroyed incriminating documents, helped suspects flee, and blocked arrests. Izzet’s successors, Tevfik Pasha and Prince Damat Ferid Pasha, agreed under pressure from the Allies, the press, and a renascent political opposition to the principle of punishing war criminals. But these officials thought that Talât, Enver, and Cemal should be punished rather than ‘the innocent Turkish nation free of the stain of injustice.’

The Yozgat trial ended with the conviction and execution in Constantinople’s Beyazit Square on April 10, 1919, of Kemal Bey, the onetime mutesarrif [kaymakam] of Boğazlıyan. His funeral the next day, which turned into an anti-Allied demonstration, was conducted with great ‘pomp and ceremony.’ ‘Numerous Young Turks [were] present,’ as well as ‘many officers and soldiers’ and medical students. One of the students, ‘holding a bunch of flowers,’ eulogized: ‘Hark oh people. . . . Hark oh Mussulmen! He whom we leave lying here is the hero Kemal Bey. The English have been ejected from Odessa, let us drive them out of Constantinople. What are you waiting for? . . . With the help of God we will soon be able to crush their heads.’ [British high commissioner in Constantinople, Admiral Somerset] Gough-Calthorpe observed that Kemal Bey ‘was treated as a hero and martyr.’ The popular mood no doubt dampened the government’s interest in punishing additional perpetrators. ‘Not one Turk in a thousand can conceive that there might be a Turk who deserves to be hanged for the killing of Christians,’ the Foreign Office commented.”[5]