The vilayet was not known for large agricultural production, despite being described as having fertile ground in 1920. Most agricultural production is kept within the vilayet, being consumed by the population. What was produced, included wheat, barley, maize, chickpeas, gall, and valonia oak. A small amount of opium and cotton was also produced in the region. Silk production was active in the southern area on a small scale, as was livestock. The area used to mine lead and nickel.

Cloth was also being produced in the Kastamonu Vilayet, made from wool and goat hair, which was mainly sold to locals. Sinop produced cotton cloth as well, with detailed embroidery. In the western part of the vilayet, rugs were produced. Sinop and Ineboli both were centers for boatbuilding.

Toponym

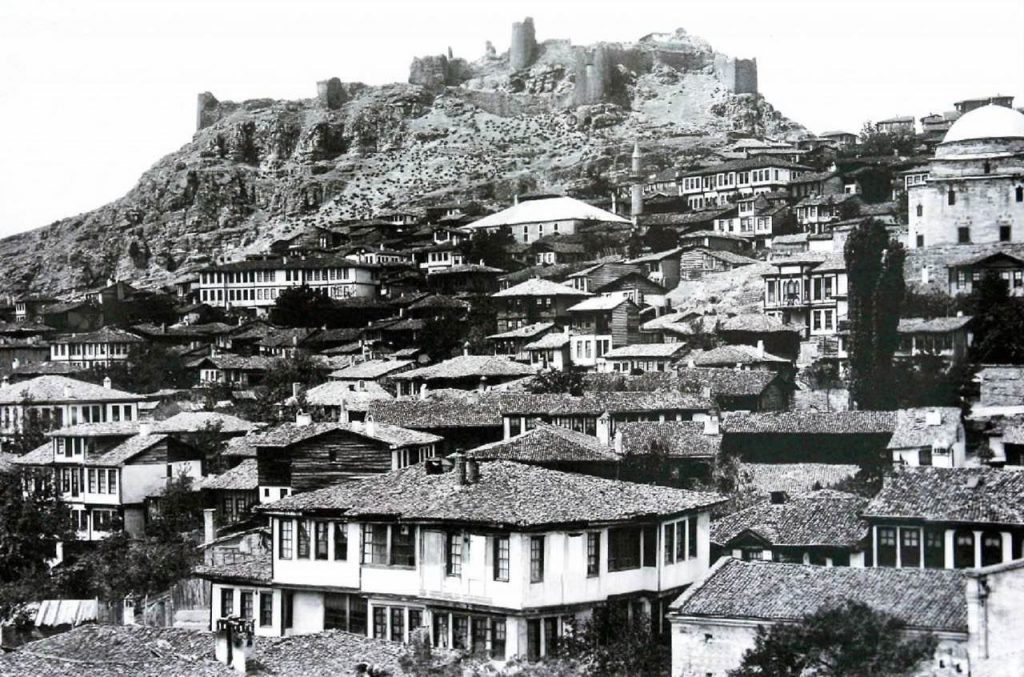

During the Roman period the town was known as Timonion (Grk.: Τιμόνιον). The current toponym probably derives from Kastra Comneni (‘Fortress of the Comnenes’”). This was the name given in the 12th century to a fortified residence of the Comnenes, a ruling noble dynasty in the Byzantine Empire. The toponym Kastra Komnenon was shortened to Kastamone, and later turkified to Kastamoni and Kastamonu.

Administration

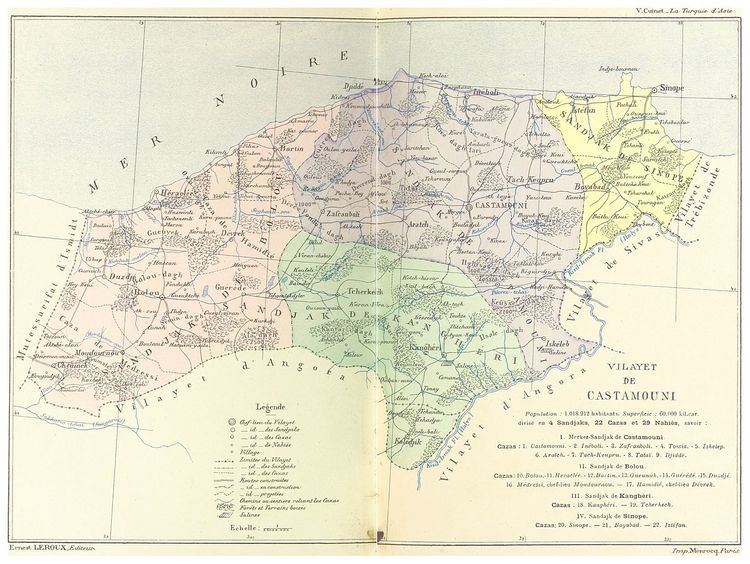

In the Ottoman Empire, Kastamonu was initially a sancak, from which the Vilâyet Kastamonu was formed in 1867 and abolished in 1922. Covering a territory of 50,000[1] square kilometers on the Black Sea coast in 1894, the vilayet comprised the four sancaks of Kastamonu, Çankırı (Kengiri, Çankiri, Çerkeş), Inebolu (Ineboli, Bolu), and Sinop (Grk.: Sinope) with 20 kazas.

Population

In the late 19th century, the overall population of the province of Kastamonu was 1,009,000[2]. On the eve of the First World War, some Armenian colonies with a total population of 13,461 lived in the province. “The prosperous Armenians of the vilayet maintained 17 churches and 18 schools, with a total enrollment of over 2,500 boys and girls. Most of the vilayet’s Armenian communities had been founded by Armenians from Nakhichevan and Yerevan early in the seventeenth century. (…) the vilayet had only isolated communities of little demographic weight, located in a Turkish-speaking region far from the war theater.”[3]

The Greek Orthodox Diocese of Castambol (Neocesarea) comprised 195 communities with 67,4724 inhabitants.[4] K. Fotiadis quotes an “official German yearbook” of 1912, according to which in the “prefecture of Kastamoni (Kastamonu)” lived 134,919 Greeks.[5]

History

According to findings that can be dated to the 13th century BC, the region has been settled since Hittite times at the latest. In the 11th century the place was taken by the Rum Seljuks and then by their adversaries, the Danishmends from Sivas.

In the 14th and 15th centuries, the town is mentioned in connection with the trade of the Genoese colonies on the Black Sea. After the collapse of the Sultanate of Rum, Kastamonu was first under the rule of the Çobanoğlu family, and in 1309 it was conquered by Candar. For the first time in 1393 and then finally from 1459 Kastamonu belonged to the Ottoman Empire. In the meantime, regional princes appointed by the Mongol Timur Lenk had ruled.

Destruction

“The boycott was preached in the Mosques and made the object of incitement against the Greeks by special emissaries, also threats and acts of oppression were applied to this Diocese (…). A proclamation was distributed and posted up, dated June 1914, and in lieu of a signature the words: ‘Atech’ (fire) Young Men’s Vengeance Association. The following is a translation. It was couched in the most violent language and calls upon the Moslems to revenge the Macedonian atrocities committed by the Greeks, and demands as well their expulsion from Turkey.

Terrorism side by side with the boycott continued until the beginning of the European War, when the Turks applied the same means of extermination here, as elsewhere.”[6]

When the vali Reşid Bey refused to proceed with the liquidation of the Armenian population of the vilayet, he was recalled and replaced by Atıf Bey, who had served as as interim vali of the Ankara province until 3 October 1915. A week after Atıf assumed office, 2,000 men were deported 300 of them from the town of Kastamonu. “These deportees from Kastamonu and Çanğırı [Çankırı] areas took the following route: Çorum, Yozgat, Inçirli, Talas, Tomarza, Hacın, Osmaniye, Hasanbeyli, Islahiye and then Meskene, Der Zor, and Abuharar. Twenty-one political internees from Çanğırı (…) were incorporated into this convoy.” [7]

After World War I, under the Kemalist regime, the persecution of Greeks continued in Kastamonu as well: “On May 13 [1921], the newspaper Eleftheros Typos revealed that ‘the prisons of Bafra are full of Greek ethnics unjustifiably incarcerated….Many Greek priests and notables from the surrounding villages of Kastamoni were arrested, led to Samsun, and committed to the local prison. They are over 500…’”.[8]

In early June 1921, Kastamonu became the deportation destination for Greek Orthodox Christians from Bafra. “A first-hand witness, Ioannis Dilmitzoglou, who managed to survive the Bafra massacre and found refuge with 100 others in Medea, Thrace, wrote an account of the plight of the Greeks in the wealthy city of Bafra in the Karamanli dialect:

‘On the morning of Saturday June 5/18, 1921, the city of Bafra was surrounded by troops and armed Turkish locals. (…) Groups of 1,000 to 1,500 women and children were captured and confined in the yard of the Bafra church. They were kept there for days, denied food or the permission to sell their possessions in order to buy food. The women were stripped, raped, and herded off to Kastamoni. This was usually done on rainy days, as the violent Turks thought those days more appropriate.’”[9]