The region of Khnus was located in the central part of the Armenian Highlands, occupying mainly the Khnus depression together with the Byurakn mountains on the western side, where two great rivers, famous in Armenian history, start from a common source, not more than 500 m apart: The Arax flows to the north, then to the east, and the Aradzan (Grk.: Arsanias, Trk.: Murat) to the south-west. The Khnus River, flowing from the north-west to the south-east was also known as the ‘Khnus Nile’: an underground river that, coming out of the earth near the village of Khert, cut the forty sanctuary-pilgrimage site, and then divided into streams to irrigate the rural pastures.

The nature of Khnus province is beautiful, the soil fertile, the waters are abundant. The region has long been famous for its cold springs, alpine meadows, and herds scattered on the slopes. Natural resources include coal, copper, silver, oil, salt, stone, mineral water, and healing mud.

A number of folk traditions were connected with those places. According to one of them, in Byurakn, on a thousand lakes, there is a god-made paradise. Adam and Eve lived in the place of the Armenian-populated village of Haramik at the foot of the eastern slopes of Byurakn, not far from which, on the top of Seli Moruk hill, near the source of cold springs, Adamord, Abel, rests. According to folk etymology, the name of Haramik village is derived from Harma, the son of the Armenian ancestor Hayk. According to another legend, the hill south of Haramik is Cayenne Hill. Cain was standing there when he was struck by an arrow fired by hunter Lamech.

The Ottoman kaza Hınıs laid isolated in the southern part of the sancak of Erzurum, but was connected with Mush, Karin and Van by busy roads. Due to its geographical location, the kaza was a link between the Taron and Sasun and the South Caucasus.

Toponym

The place-name derives from the Arabic word for castle ‘Hisn’. The date of the construction of that castle is unclear. According to the Ottoman explorer of the 17th century, Evliya Çelebi, it was built by an uncle of the Turkmen Ak Koyunlu ruler Uzun Hasan.

In Armenian the region was also called Varazhnunik or Hark, according to the two historical districts (cf. map ‘Expansion of the House of Mamikonian’ in the right colum).

Administration

In the 17th century, a sancak Hınıs was established in the Erzurum Vilayet, and in the 18th century, a hükümet Hınıs was established as part of the Bayazid Paşalık. With the Ottoman administrative division in the 1860s, the province of Khnus re-entered the Erzurum vilayet.

Armenian Population

After the kaza Erzurum, the kaza Hınıs had the largest Armenian population before World War I, 21,382. Armenians lived in 25 settlements of the kaza and maintained 21 churches, four monasteries and 17 schools with 871 students.[1]

According to other Armenian sources, as of 1880 the kaza had 171 villages, of which 139 were Kurdish, 11 were Armenian, two were Turkish, and 19 were mixed. The total population was 22,518 people, of which 13,382 were Kurds, 8,552 were Armenians, and 584 Turks. According to E. Melikyan, in 1914, the kaza Hınıs had 336 villages, of which up to 38 were inhabited by Armenians. The Kurdish villages occupying the former Armenian settlements, which were located mainly in the mountains, were small, in most cases having only 5-6 houses. The number of Armenians in the province in 1914 was 25,000.[2]

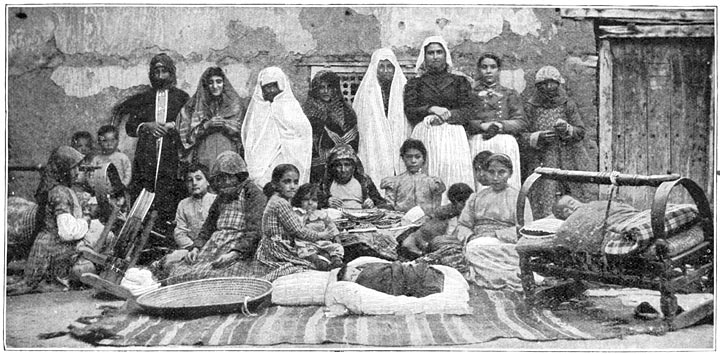

The population was engaged in agriculture (wheat, barley, millet, flax), cattle breeding, poultry farming, gardening, beekeeping, fishing. The cattle of the kaza of Hınıs was highly valued not only in the markets of Erzurum, but also in the neighboring vilayets. Crafts were widespread. Hınıs cheese and carpets with embroidered patterns were very popular. The paint was made from plants.[3]

The educational work in the province of Khnus had progressed especially in the 1870-80s. Information is preserved about the cultural organizations of the Mamikonian Society (founded 1878 – 1880) and the Youth Union (founded 1910). The gospels of Gopal, Halilcavuş, Khnus Berd (Hınıs), Khozli, Haramik, Burnaz, and Maylu were famous.

Two lists of Armenian settlements

- Խնուս բերդ Khnus Fortress (Hınıs)

- Աղճամելիք կամ Խաչամելիք – Aghchamelik’ or Khachamelik’ / Ağçamelik’

- Անտոալագոմ – Antoalagom

- Արոս – Aros

- Գաբրիելի գոմ – Gabrieli gom

- Գըզմուսա – Gezmusa

- Գոլճիսար կամ Խոլհասար – Golchisar or Kholhasar

- Գոպալ -Gopal

- Գովանդուկ կամ Կովանտուկ – Govanduk or Kovantuk / Gövenduk/Geovenduk

- Յահիա – Yahya

- Ելպիս – Elpis

- Եզրդլու կամ Գասպարի գեղ – Ezrdlu or Gaspari gegh

- Ենիքեոյ – Yenik’eo

- Թանտըրլի կամ Թոնդրակ – T’antghrli or T’ondrak

- Թարաձիգ – T’aradzig

- Լաքպուտաղ – Lak’putagh

- Խալիլչաուշ կամ Խաչալույս – Halilçavuş or Khachaluys

- Խըռթ – Khghot‘

- Խըրմխայա – Khghrmkhaya

- Խոզան – Khozan

- Խոզլու – Khozlu

- Հարամիկ – Haramik

- Մարուֆ կամ Մարդ – Maruf or Mard

- Մժնկերտ – Mzhnkert

- Մոլլատաուա – Mollatava

- Ղարաչոբան – Gharachoban / Karaçoban

- Ղարապուրաք – Gharapurak‘

- Ղարաքյորփի – Karak’örp’i

- Շապատին – Shapatin / Şabadin

- Չեվիրմե կամ Չաուրմա – Çevirme or Çaurma

- Պեկուրաի – Pekurai

- Պուռնազ կամ Բուռնազ – Purnaz or Burnaz

- Սալուսրի կամ Սարուսլի – Salusri or Sarupi

- Սաոլու կամ Սառլի – Sarlu or Sarli

- Սոկյութլի – Sokyut’li

- Դուման – Duman

- Փայկ կամ Հայկ – P’ayk or Hayk

- Քաղքիկ – Kaghk’ik[4]

Karaçoban: 2.571 Armenians

Gövenduk/Geovendug: 1556 Armenians

Burnaz/Purnak: 449 Armenians

Karaköpru: 1.161 Armenians

Khert/Xert: 408 Armenians

Khozlu/Xozlu: 1.770 Armenians

Yeniköy: 451 Armenians

Çevirme: 1.361 Armenians

Ağçamelik: 318 Armenians

Pazkig: 876 Armenians

Şabadin: 391 Armenians

Maruf: 338 Armenians

Duman: 398 Armenians

Yahya: 305 Armenians

Khırımkaya/Xırımkaya: 425 Armenians

Salvori: 245 Armenians

Durukhan/Duruxan and Gopal: 1.375 Armenians

Sarlu: 441 Armenians

Mejengerd: 75 Armenians

Haramig / Haramik: 898 Armenians[5]

History

Although there exists little information about the past of Hınıs, the oldest written records about the region date back to the 1400s. Hınıs, which remained under Armenian and Iranian rule for a long time, later passed into the hands of the Byzantines. It has been populated by Armenian and Kurdish communities for centuries. Hınıs, which came under the domination of the Seljuks with the occupation of Man(t)zikert in 1071 passed then again into the hands of the Iranians, but was eventually occupied by the Ottomans.

Until the 8th century the Armenian dynasty of Mamikonian ruled in the territory of Khnus. Later, it was ruled by the Byzantine emperors, the Mrvanyans, the Shah-i-Armenians of Khlat, the Seljuks, and the Mongols. With the Iranian-Ottoman division of Armenia in 1555 and then in 1839, it came under Ottoman rule. Until the 19th century, the dependence of Khnus province, as well as a number of other provinces of Sasun and Mush, on the Ottoman central government was limited. Kurdish tribes settled in the region mainly during the Ottoman-Iranian wars. The fight of Kurdish beys and sheikhs against Iran were sponsored by the Ottoman authorities, which used the Kurds also to suppress the Armenian liberation struggle.

The region of Khnus was the cradle of the Tondrakyan movement. The direct heirs of the scattered and persecuted Paulicians in Armenia appear to be the T(h)ondraks (mid-9th to 11th century), named after their center, the village of Tondrak in the historical Armenian province of Turuberan, north of Lake Van, where the priest Smbat Zarehavantsi (Smbat of Zarehavan) had gathered them. Initially persecuted only by the leadership of the Armenian Church, whose privileges they dared to challenge, the Tondraks were later increasingly oppressed by the Byzantines. Byzantium felt particularly challenged when it attempted to annex large parts of Armenia in the 1030s, and was directly confronted with the Tondraks, whose movement now took on the character of national resistance.

There were many stone tonirs (also tandoor, tanour) near the village of Tondrak, from which, presumably, the name of both the village and the sect originates. In the village of Zeirme resided Tondrak descendants who secretly followed the ancestral sect, thus avoiding persecution by the authorities and the church. They kept the Gospel of the “Key Truth” written in 985 and transmitted from distant predecessors. According to some sources, they buried that Gospel during the 1915 genocide in their native land, hoping that they themselves would survive and return to the land of their ancestors.

Another example of “key truth” was discovered by F. Coniber in the manuscripts of Echmiadzin.[6]

Destruction

“The Armenian villagers in this kaza did not suffer the fate of other localities in the region, but were massacred on their native ground. As elsewhere, the operations began with the arrest of the local elites. (…) The first massacres were perpetrated in the kaza in April [1915], when Hoca Hamdi Bey, the commander of a squadron of çetes, led his men, billeted in the Armenian village of Gopal in the eastern part of the kaza, in an attack on to neighboring localities, Karaçoban (pop. 2,571) and Gövenduk/Geovendug (pop. 1,556). The çetes massacred a number of peasants, abducted young women, and plundered the villages.”[7]

The remaining villagers of Karaçoban had their throats cut in the neighboring gorges of Çağ on 1 June 1915. The town of Gövenduk suffered a similar fate, on the same date, along with the villages of Burnaz/Purnaq (pop. 449) and Karaköprü (pop. 1,161), which were victims of assaults at the hands of the Special Organizationthugs commanded by Hoca Hamdi Bey. Their population was liquidated by knives in an isolated spot. The inhabitants of the village of Haramik (898 individuals) resisted 15 days of assaults by the bandit group led by the Kurdish chief, Feyzullah[8], until their ammunition run out, inflicting heavy losses on the Kurds.(9)

Hınıs / Khnus Town

Hınıs was divided into districts. The houses of the city, without exception, had flat earthen roofs, the streets were narrow. Back in the 13th century, Khnus was an important trade hub on the Khoy-Van-Berkri–Manazkert–Erzurum–Baberd–Trebizond road. At the beginning of the 20th century, the town still had quite a lively trade, its abundant market with dozens of trade stalls. It was closely connected with Erzurum, Bitlis and Mush. The livestock products and honey that Hınıs exported were famous.

In 1587, the Gospel was copied in Hınıs. In the beginning of the 20th century, the cultural life of Hınıs was quite lively. There was a school next to Surb Astvatsatsin (Holy Mother of God) Church with more than 100 students and 4 teachers. The most remarkable structure of the town was its fortress, about which no information is reported in ancient Armenian sources. Its first mention is the testimony of an Italian traveler (1471 – 1478). The next important evidence belongs to the Ottoman author andexplorer Evliya Çelebi (1647), who considered the fortress as “impregnable”. By the end of the 19th century, the fortress of Hınıs was already completely ruined and deserted.

There were an old and a new church in the city itself. The most famous of them was the arched Surb Astvatsatsin, which was located on the bank of the river, on a separate rock. There were two bridges over the river, one of which was a tastefully built stone bridge. There were various antiquities on the eastern side of Hınıs.

Population

There is no direct information on the medieval population of Hınıs, but indirect descriptions show that Khnus/Hınıs was quite a large settlement at that time. The data on the population in the 19th and 20th centuries are very contradictory. According to official Ottoman statistics, the non-Muslim population of Hınıs, like other cities in Western Armenia, has been deliberately reduced. According to more reliable testimonies of individual authors, in 1800-1830 the population of the town reached 5,000 people, of which 80% (4,000) were Armenians; in 1830-1850 – 6,000 people, of which 3,000 were Armenians. In the following decades, the number of Armenians continuously decreased due to violence and persecution. In 1909, out of 900 houses in Hınıs, only 325 houses (with 2,163 inhabitants) were Armenian. In 1914, out of its 8,000 inhabitants, only 2,000 were Armenians. In 1916, only 200 Armenians remained here. The honored actor of the Armenian SSR Garnik Karapetyan was born in Hınıs in 1917.

The town’s population was engaged in agriculture, animal husbandry, particularly horse breeding, handicrafts and trade. The main occupation of the Armenians was handicrafts and trade.[10]

Destruction

In May 1915, the Ottoman authorities arrested 150 Armenian notables from Hınıs and shot them. In 1918 the last Armenian inhabitants of Hınıs migrated to Eastern Armenia with the retreating Russian troops.

Under the Kemalist regime, Hınıs became a destination for Greek deportees from Zurnatzanton and Kozlaranton.[11]