Population

“Before World War I, Siirt and the surrounding villages formed a Christian enclave. About 60,000 Christians (25,000 Armenians, 20,000 Syrian Orthodox, 15,000 Chaldeans) lived here.”[1]

Armenian Population

According to the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople, around 1914 there lived 4,437 Armenians in nine localities of the kaza of Siirt, maintaining three churches, one monastery and two schools with 330 students.[2]

Syriac Population

“Before World War I, the town and its surrounding villages were a Christian enclave, but with considerate variation. Immediately surrounding Sa’irt, the Christian communities belonged to the Chaldean Church. [The Chaldean priest of Mardin, Joseph] Tfinkdji noted a total population of 5,430 persons in the Chaldean diocese, with 21 priests, 31 churches, 7 chapels, and 9 schools. Of the Chaldeans, 824 lived in the town and the rest in 36 surrounding villages. The Agha Petros list noted 40 Nestorian Assyrian households in the town.

To the northwest was an area of mixed Armenian and Syriac Orthodox villages with some Yezidi presence. To the east, beyond a mountain range, was a region of mixed Chaldean and Nestorian villages.”[3]

Siirt Town

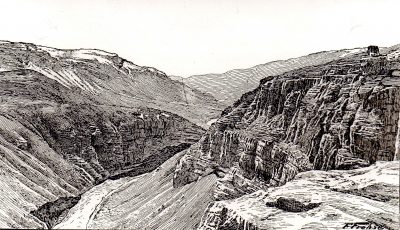

Situated not far from the confluence of the Western and Eastern Tigris Rivers, in the lower reaches of the Baghesh (Bitlis) River, 5-6 km from the Sgherd River, on a plateau. The altitude is 1100 m above sea level. The climate is hot, continental. The lands are irrigated by the waters of the Tigris and its tributaries. There are limestones, metal veins, hot water springs nearby.

In ancient times, the region of Aghdznik was the center of the Kherhet or Serkhetk province, hence its name. In the 16-18th centuries it was part of the Ottoman province (vilayet) Diyarbekir. Sgherd has existed since ancient times. Some connect its foundation with the name of Tigran the Great, others with the name of Skyord. According to the sources, Siirt was quite a prosperous city in the Middle Ages.

There are ruins of old Armenian fortresses around the city. There are polished rocks on different sides of it, on which Armenian lithographic inscriptions are carved. Before the First World War, the city had three churches.

Siirt and its surroundings are known for their viniculture. In Siirt the residents were equally engaged in handicrafts, trade, agriculture and gardening. Armenians were mainly engaged in crafts and trade. Common trades included coppersmithing, blacksmithing and armaments, textiles and weaving, shoemaking and tailoring. The copper vessels made here were especially famous, some of which were sold outside the district.

From the second half of the 19th century, larger enterprises of this type gradually emerged – leather, textile, shawl ‘factories’, which, however, did not differ much from home-made enterprises. In Siirt, rich in limestone, there were several lime factories, some of whose products were exported.

In terms of foreign trade, Siirt’s position has almost always been favorable. In ancient times it was situated near the ‘royal road’ from Persia. Later it always had a convenient position in relation to the caravan roads connecting Armenia with Mesopotamia and the west, being at one of their junctions. In modern times, several highways and rural roads came out of the city. Siirt was a transit point for foreign trade, participating in that trade with its handicraft products and agricultural products. The city had its own market, where at the end of the 19th century there were up to 100 shops and kiosks.

Siirt was a unique agricultural settlement. Some of its agricultural products – melon, cucumber, fig, pomegranate – had a good reputation throughout the Ottoman Empire. Siirt was famous for its grapes. A local grape called Shafi was cultivated here, which is praised by locals and foreign travelers alike.

Population

The Prussian Captain Helmuth von Moltke (later Field Marshal General) – detached from 1836 to 1839 as instructor of the Ottoman troops – reported from Siirt that there were 600 Muslim and 200 Christian families.[4]

Having a significant Chaldean and some Armenian population at the beginning of the 20th century, the current indigenous population of the city is Arab.[5]

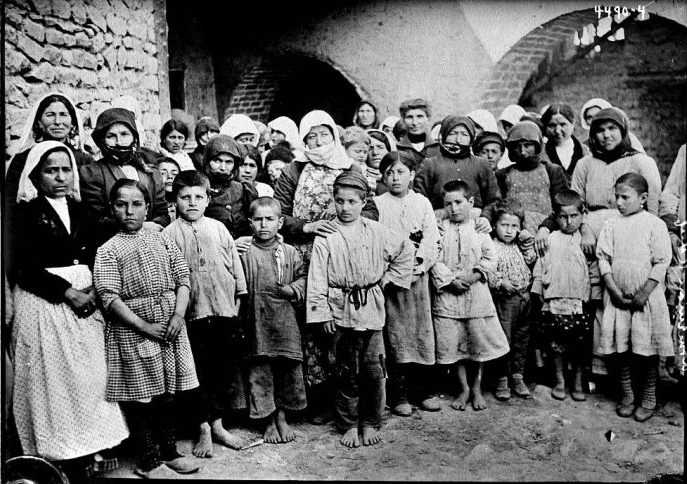

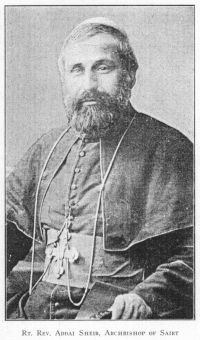

“In Se’ert (Siirt) and the surrounding villages lived more than 12,000 Christians: Syrians, Chaldeans and Armenians. The Chaldean community was led by the famous blessed Metropolitan and martyr Mor Addai Sher. There was also a monastery and schools for boys and girls in the city, as well as two orphanages run by three monasteries. In short, Se’ert was a flourishing city richly populated by Christians.”[6]

Syriac Population

From 1858 to 1915, the city of Siirt was the episcopal see of the Chaldean Catholic Church.

Armenian Population

Siirt had 5,600 Armenian inhabitants in the 18th century. During 1800-1830 Siirt’s population was about 17,000, of which 10,000 were Armenians, in 1830-1850 6,000 of the 15,000 inhabitants were Armenians. During the massacre of 1895, the Turks looted the church, the prelacy, the school, forcibly converted most of the Armenian population to Islam, massacred the clergy, and barred women.

On the eve of World War I, there were 13,000 inhabitants, of which 6,000 were Armenians, the rest were Turks, Arabs, Kurds and Syriacs. In Siirt, the Armenians maintained the Surb Tatevos-Bartoghimeos Apostolic Church, a Catholic and a Protestant Church. The center of the diocese was the Surb Hakob Monastery (St Jacob).

Destruction 1895 and 1915

“The massacre [in Diyarbekir, 1895] was followed by Kurdish attacks on nearby Armenian and Assyrian villages and towns, including Nisibin, Midyat, and Siirt, and on two Yezidi villages. In most, churches were burned and priests murdered.”[7]

“One of the most cowardly acts of murder in the history of Armenia”: The Siirt Massacre (June 1915).

The following account is taken from the memoirs published close to the event by Rafael de Nogales, a Venezuelan mercenary in the Ottoman army:

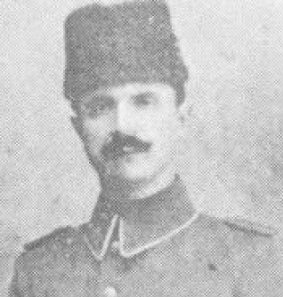

“On the way to Sairt, I met some officers of the Başkale Volunteer Battalion, who told me with a satisfied expression how the government in Bitlis had already prepared everything and was only waiting for Halil Bey’s signal to commit one of the most cowardly acts of murder known to the history of modern Armenia.

(…) On the 18th, before noon, we arrived before Sairt, which betrayed its Babylonian origin with its white houses, tapering upward. Six minarets, one of them leaning, stood out like alabaster needles against the blue sky of Mesopotamia. Herds of cattle and black buffalo grazed quietly on the plain, woolly dromedaries slumbered around a lonely spring.

I was suddenly snatched from the comfort into which this pretty picture had momentarily plunged my tortured mind by a ghastly sight: on a hill beside the road lay thousands of corpses, half-naked, bloody, in wild confusion; each victim where he had been broken to pieces under the bullets and knives of his executioners. Here and there the limbs of the dying twitched, while crows pecked out the eyes of the dead and dogs tore the entrails from their bodies. Under the crushing impression of this spectacle we rode on, our horses often having to step over corpses, and finally came to Sairt, where the police and mob were still busy looting the houses of the Christians.

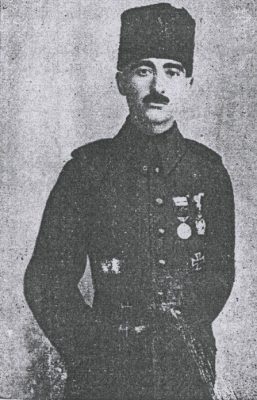

In the seraglio I met with several sub-prefects of the province at a meeting presided over by the chief of the provincial gendarmerie, Captain Nazim-Efendi, the latter of whom had presided over the slaughter in person.

From his speeches I immediately gathered that it had been decided the day before by Cevded Bey, and that the latter had left early in the morning for Bitlis to begin the other butchery of which the officers of Başkale-Tabur had spoken.

In the meantime, I had taken lodgings in a fine house belonging to the Nestorians, which, like all of them, had been plundered. All that was left of the furniture were a few broken chairs; the floor and walls were stained with blood. In a forgotten corner I found an English dictionary with a small picture of the Virgin Mary, which someone had hidden here in a hurry.

After a short rest I went to the military casino, where several officers who had been under my command during the siege of Van were already waiting for me. With them I could follow in detail the tragedy that the city of Sairt offered. Among the repulsive things that I had to witness with a smile on my lips was the procession, with a detachment of gendarmes at the head, leading in their midst a venerable old man. His black tunic and mulberry-colored beret indicated that he was a Nestorian bishop. Drops of blood trickled down from a wound on his forehead, which, as they trickled down his pale cheeks, seemed to turn into red martyr’s tears. As he passed us, he fixed his gaze on me, as if he felt that I, too, was a Christian; then he strode on in the direction of a hill, where he stopped, arms crossed, in the midst of his flock, which had gone out to him on the road of death, and, mangled by the iron of his murderers, fell down. Then again others passed by with corpses of children and old men whose heads dragged on the stone pavement, while the passers-by spat before the dead and accompanied them with imprecations.

Thus, before my eyes, deeply sad and blood-soaked images unrolled, until finally, tired of such misery, I went to my quarters, determined not to continue to serve under the flags of Halil-Pasha, who tolerated such crimes. (…) In those days, human life had very little value there. Woe to anyone who had golden teeth! The Kurds would have managed to follow him for days in order to murder him and then tear out his golden teeth.”

Excerpted and translated into English from: Nogales, Rafael de: Vier Jahre unter dem Halbmond: Erinnerungen aus dem Weltkriege. Berlin: Verlag von Reimar Hobbing, (1925), p. 89-91

Testimony on the Martyrdom of the Chaldean priest Gabriel

“Then Qasem [Trk.: Kâzım] and his gang attacked the house of the priest Gabriel the Chaldean and led him to prison. Once in prison, they made him take off his clothes and stabbed him with daggers and swords. At each stabbing, they said to him, ‘Deny your Christ and confess Islam.’ But that martyr cried out, ‘I die in my glorious faith.’ He remained so until he breathed his last. He too was beheaded. They threw his head on a pile of excrement near the house of Ahmed Agha.”

© Foundation for the Preservation and Promotion of the Aramaic Heritage. Excerpted and translated from: http://www.jahrestag.stiftung-aramaeisches-kulturerbe.de/siirt.html