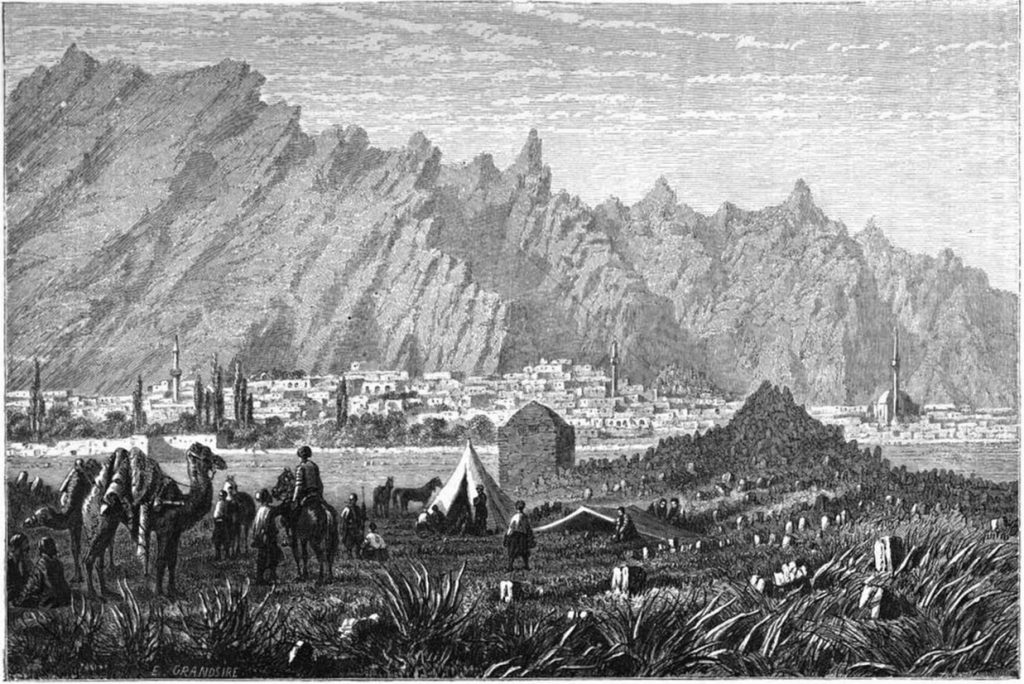

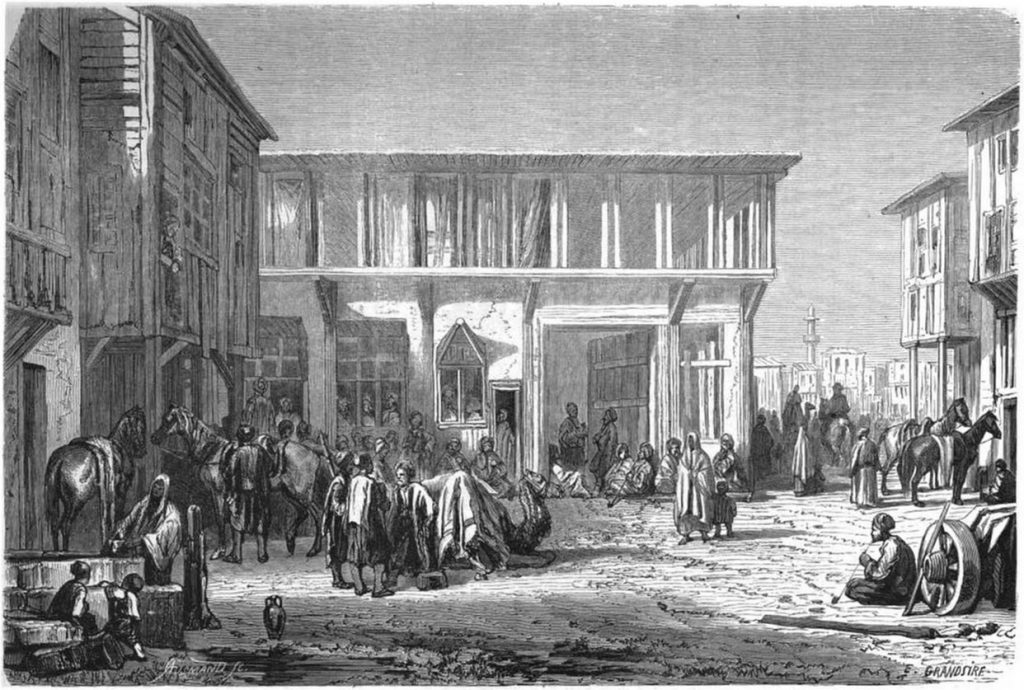

“Located in the middle of a vast plateau in the southwestern part of the sancak, Sivrihisar nestles in a loop of the Sakaria.”[1]

Toponym

The Greek toponym Spaleía (‘arbors’), first documented in the year 610, was the original name of the district’s administrative center Sivrihisar.[2] During Roman rule, the town was called Justinianoupolis.

The town of Sivrihisar lies 13 km north of the historical site of Pessinus (today the village Ballıhisar), at the foot of a high double-peaked ridge of granite, which bears the ruins of a Byzantine castle, and gives the town its name (‘pointed castle’).

Population

According to the French geographer Vital Cuinet, there were 7,000 Muslims and 4,000 Armenians in the kaza of Sivrihisar at the end of the 19th century. The Armenians of Sivrihisar had immigrated from Gandzak (Ganja, Gəncə) and Karabakh in the early 17th century. “In 1914, this colony boasted a population of 4,265. The Armenians of Sivrihisar were reputed to be prosperous; some earned a living farming land on the outskirts of the town.”[3] At the eve of the First World War, the Armenian community of Sivrihisar maintained two churches and four schools with an enrolment of 990 pupils.[4]

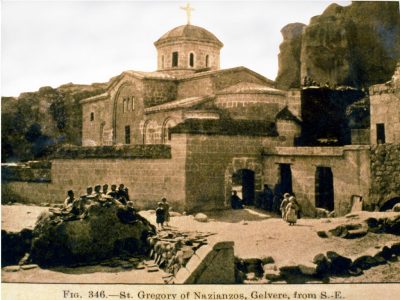

One of Sivrihisar’s two Armenian churches, the Church of Holy Trinity was restored until 2015.

Notable Armenians

- Bedros IV. Sarajian (Պետրոս Դ Սարաճյան, 1870 Sivrihisar – 28 September 1940, Beirut): genocide survivor, Armenian-Apostolic bishop; 1940 catholicos of the Great House of Cilicia

- Moushegh Ishkhan (Մուշեղ Իշխան; born as Jenderejian, 1913 Sivrihisar – 12 June 1990 Beirut): genocide survivor, poet, writer and educator

Language as homeland

“The Armenian language is the home

and haven where the wanderer can own

roof and wall and nourishment…”

(Poet Moushegh Ishkhan)

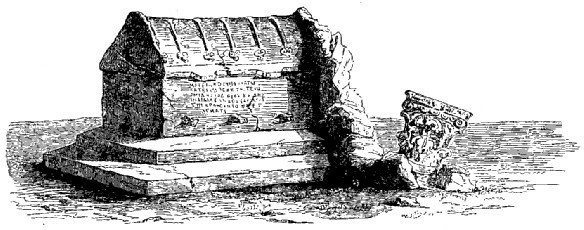

Ancient city of Pessinus – Village Ballıhisar

“From the exit Sivrihisar, today Ballıhisar, the archaeological city of Pessinus is about 14 km away. The archaeologist and historian John Garstang wants to equate it with the Hittite Šallapu. Pessinus is considered the place of origin of the Anatolian cult of Cybele, which spread from here. In the sanctuary there was a black meteorite, which was taken away to Rome in 205/4 BC. According to legend, the first temple was built here by King Midas (8th century BC). Remains of the later Hellenistic temple with large display staircases have been preserved. Belgian excavations have been taking place there since 1967. Particularly impressive are also the black contours of the sacred mountain Dindymos.”[5]

At the beginning of the 20th century, the village of Ballihisar was inhabited by 300 Armenian families. About their extermination see below the section “Destruction”.

Destruction

“On 12 August [1915], the deportation order was published. On Saturday, 14 August, [Father Hovhannes] Kizirian was received with all the honors at the konak, where the vali, Ali Rıza, informed him that the Armenian population had a week to make preparations to leave. The clergyman tried in vain to obtain an exemption for the families of conscripts. He himself left with the last convoy on 19 August. In the meantime, he witnessed the looting of Armenian homes. All the caravans were directed toward the railroad station in Eskişehir, where thousands of deportees from the west were camped out under precarious conditions. At this point, there arrived an order to the effect that the families of conscripts should be dispersed in the surrounding villages. Thereafter, the fate of the Armenians of Sivrihisar was indistinguishable from that of those deported either by rail – in two-tiered stockcars originally meant for sheep – or on foot to Bozanti, the gateway to Cilicia. According to survivors’ reports, the deportees from Sivrihisar were dispatched toward Rakka and Der Zor. The overwhelming majority of them died on the way when they were not killed before setting out, victims of the final massacres perpetrated in fall 1916. (…)

Balahisar [Ballıhisar], a village southwest of Sivrihisar, had, in 1914, 300 Armenian households. On orders from the kaymakam, Kamil Bey, the men of village were arrested and massacred near Köprüköy in August 1915 with the complicity of Faik Bey, a civil servant employed in the Registry Office, and Mehmed Bey, an official in the Land Registry Office.”[6]