Administration

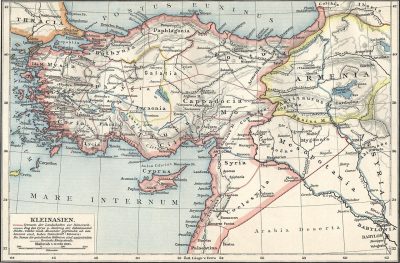

In the Ottoman Empire, Çankırı was the capital of a sancak in the Anatolia Eyâlet, later Vilâyet Kastamonu.

Toponym

The ancient name of the city was Gangra (Grk.: Γάγγρα; also: Gangres). According to 1st-century B.C. writer Alexander the Polyhistor the town was built by a goat herder who had found one of his goats straying there; but this origin is probably a mere philological speculation as gangra signifies ‘a goat’ in the Paphlagonian language.

In the writings of the 2nd-century A.D. Greco-Roman writer Ptolemy, the city is referred to as Germanicopolis (Grk.: Γερμανικόπολις). It was named Germanicopolis, after Germanicus or possibly the emperor Claudius, until the time of Caracalla.

The continuity of the city’s original name from ancient times across languages is of note: Hangara for the Arabs, Gagra for the Jews and Tzungra or Kângıri or Çankıri for the Turks.

Population

According to the statistics of the Armenian Apostolic Patriarchate of Constantinople, there lived 1,000 Armenians in the sancak of Çankırı on the eve of the First War. They were concentrated in the administrative seat and possessed one church and one monastery.[1]

History

Gangra was a town of Paphlagonia that appears to have been once the capital of Paphlagonia and a princely residence, for it is known from Strabo that Deiotarus Philadelphus (before 31 BC–5/6 A.D.), the last king of Paphlagonia, resided there. Notwithstanding this, Strabo describes it as only “a small town and a garrison“.

Gangra was absorbed into the Roman province of Galatia upon the death of Deiotarus in 6/5 B.C.

In Christian times, Gangra became the metropolitan see of Paphlagonia. Hypatios, bishop of Gangra, is considered a saint in the Orthodox Christian tradition. He was killed by Arians on his return from the Council of Nicaea (325 AD), in which he took part.

In the 4th century, the town was the scene of an important ecclesiastical synod, the Synod of Gangra. There is disagreement about the date of the synod, with dates varying from A.D. 341 to 376. The synodal letter states that twenty-one bishops assembled to take action concerning Eustathius of Sebaste and his followers. The synod issued twenty canons known as the Canons of Gangra; these were declared ecumenical by the Council of Chalcedon in 451. Under these canons, the sect disowned marriage, disparaged the offices of the church, held conventicles of their own, wore a peculiar dress, denounced riches, and affected special sanctity. The synod condemned the Eustathian practices, declaring however that it was not virginity that was condemned, but the dishonoring of marriage; not poverty, but the disparagement of honest and benevolent wealth; not asceticism, but spiritual pride; not individual piety, but dishonoring the house of God.

Over the centuries the settlement witnessed the hegemony of many cultures and peoples, such as Hittites, Persians, ancient Greeks, Parthians, Pontic Greeks, Galatians, Romans, Byzantine Greeks, up to the Seljuks and finally the Ottoman Turks.

Destruction

At the beginning of the Armenian Genocide, on ‘Red Sunday’, 24 April (11 April according to the old calendar), 1915, about 150 Armenian intellectuals were deported from Constantinople to Çankırı and interned there. Raymond H. Kévorkian explains the choice of Çankırı as the place of internment with the small percentage of Armenian population in the province of Kastamonu, especially in the town and sancak of Çankırı.[2]

The internees from Constantinople lived in the Çankırı under “conditions of house arrest, unlike the political prisoners in Ayaş who were confined in a barracks. Each internee had to provide his own means of subsistence and rent lodgings from a local landlord. Several witnesses say that the prisoners formed groups based on personal affinities, with each man playing a particular role in these reconstructed households. After a brief stay in Çankırı, eight people were authorized to return to Istanbul on 11 May [1915]. (…) Shortly afterward, a second group comprising some 20 people was also authorized to return to the capital. Interpretations as to why these men were released vary widely, depending on the source. In the cases of Gomidas [Vardapet Komitas] or [Dr.] Torkomian [Torgomian], for example, it is said that diplomatic circles in Istanbul or court circles interceded on their behalf. (…)

Once these adjustments had been made, it was decided to proceed with the liquidation of the remaining deportees. According to an Armenian survivor, the first group of those exiled to Çankırı, comprising 56 people, was put on the road on 11 or 18 July 1915 and slain to a man shortly thereafter. The second convoy of ‘intellectuals’ set out on 19 August. (…) These men were interned in the prison in Angora [Ankara] from 20 to 24 August and on the evening of the 24th, with the exception of [the journalist Aram] Andonian, who had accidentally broken his leg and been transferred to the hospital in Angora, all were put on the road and killed a few days later in the vicinity of Yozgat.

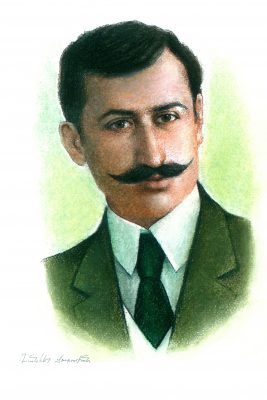

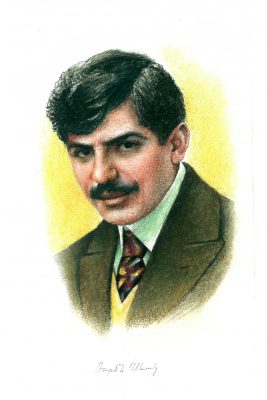

It seems that a special fate was reserved for five men, among them the physician and writer Rupen [Ruben] Sevag [Sevak] (Chilingiran) and the poet Daniel Varuzhan [Varujan]. These two were put on the road after the second convoy set out and murdered by twelve çetes six hours from Çankırı, near the khan [Trk.: han; karavanseray] of Tüney, on 26 August. There were only 37 internees left at Çankırı by the time Atıf Bey was named vali of Kastamonu early in October. Among them was Diran [Tiran] Kelekian, who (…) was murdered at eight o’clock that night [of 20 October] on the road between Yozgat and Kayseri, near the Çokgöz Bridge over the Kızılirmak. It is probable that the order to kill him came from Istanbul.”[3]

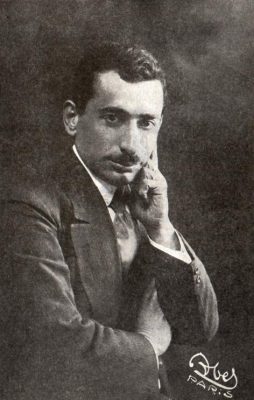

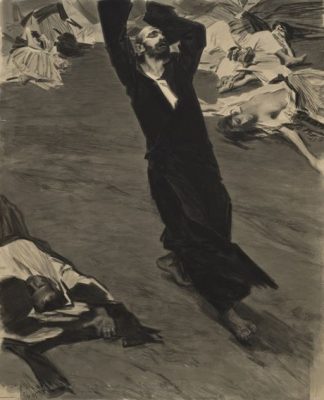

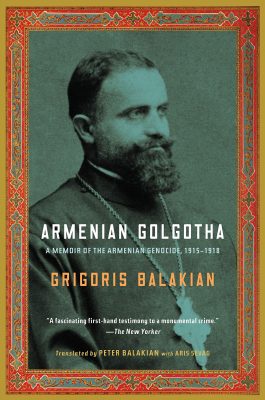

Grigoris Palagian (Balakian): Life in Chankiri Armory

The former Armenian Apostolic prelate of Kastamonu and Çankırı,

Grigoris Palagian, was one of the Armenians arrested on 24 April 1915 in Constantinople and interned in Çankırı. In his memoirs Armenian Golgotha (Vol. 1, 1922) he published an incomplete list of 69 fellow sufferers[4] and wrote the following about their everyday life during the first weeks of their internment:

“Unfortunately, it was possible to obtain only half of the names of our comrades exiled in Chankiri, and that with great difficulty; there were besides these, noble and self-sacrificing youths from the humble class of society, and I so wish I could remember all of them here. (…)

How can I forget those nights when hundreds of intellectuals, clergymen, doctors, editors, teachers, wealthy merchants, and bankers lay piled next to one another on the hard boards of the armory, dozing because it was impossible to sleep? But when blacker days came, we would think of these times as pleasant ones. Still, these conditions were truly unbearable; and so everyone tried his best to make do and, thanks to the power of many, to get some food. But the majority, who had no money, appealed to me as a spiritual father. Alas, sharing their penury as well as their fate, I was of scarcely any service to them. As the former prelate of Kastamonu and Chankiri, however, I had some influence with old friends, and so it was possible to get some bedding, blankets, and carpets from fellow Armenians in the region, so that at least we were spared sleeping on the hard boards.

Finally, two weeks alter, we were allowed to leave the armory. Everyone hurried to find a place to stay with friends or else elected to remain in the intimate circle of compatriots to pass these tedious days of waiting for our fate to be decided.”(5)