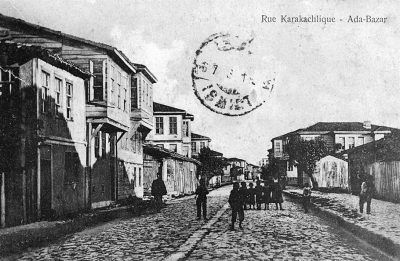

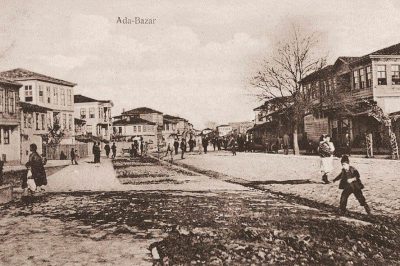

County and Town Adapazarı (Gr: Sangaria)

Location and Toponym

In late antiquity, the Eastern Roman Emperor Justinian (527-565) had a stone bridge built at the strategically important Sangarios River (Gr: Σαγγάριος, Trk.: Sakarya) crossing at today’s Adapazarı, after the strong current had repeatedly swept away the pontoon bridge. Sometime after the fall of Constantinople to the Turks in 1453, the settlement was renamed Ada (Island), as it lay between two sides of the Sakarya River. At on time, Adapazarı was also known as Garlic Island (Sarımsak Adası), presumably because of the large quantities of garlic grown there.

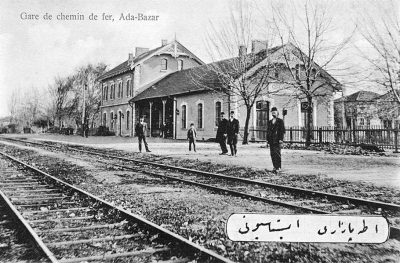

The construction of the Anatolian Railway, which reached Adapazarı in 1898, contributed significantly to increasing prosperity, of which the town’s Armenian and Greek merchants and craftsmen also benefitted. The town owes its current name of Apazarı (Island Marketplace) by virtue of its having been a center for brisk trade and commercial activity.

“It is said that Adabazar was founded by Armenians from Sivas (Sebastia) fleeing from the invasions of Tamerlane in the late fourteenth century. Built in a dry lake, the town was originally named Donigashen (Tonikashen), in honor of a village elder. Armenians from Agn [Akn] , Tokat, Iran, and later from Kesaria [Kayseri] and Bardizag also settled there. Turks and Greeks began to move to Adabazar as it developed into a mid-sized town. (…) Every year, it sent 15,000 crates of eggs and 100,000 chickens to the capital.

By the early twentieth century, Adabazar was a town with a library, a publishing house, and a number of modest hotels aınd khans, pharmacies, grocery stores, tanneries, factories and foundries, the proprietors of many being Armenian.”[1]

Population

Around 1890, the town of Adazarı had 24,000 inhabitants. Information on the composition of the Christian population or the number of Armenians is not uniform: By Vital Cuinet’s count, there were 900 Armenians, 880 Greeks, and approximately 5,000 Muslims living in Adapazarı in the late nineteenth century.[2] Upheavals in the Caucasus region during the Russo-Ottoman War of 1877-78 and then the disastrous Balkan wars of 1912-13 created a large displacement of Muslims, many of whom were relocated to cities in western Asia Minor. Some 25,000 to 35,000 Circassians settled in the Adapazarı kaza following the Ottoman defeat in the 1877-78 war. According to Minas Gasapian’s calculation, by 1913 the number of Armenian households had increased to 2,100.[3] On 4 August 1915 and at the beginning of the deportation of the Armenian population, the Consul General at the German Embassy Constantinople noted: “Adapazar with about 25,000 inhabitants, half of which are Mohammedans, approx. 1,500 Greeks, the rest Armenians (1,500 Protestants among the latter), was to be evacuated today by the Armenian inhabitants; a supply of bombs was found in Adapazar and the Armenians claim that it was set up at the time, i.e. under Abdülhamid, with the support of the Young Turks.”[4]

Most of Adapazarı’s approx. 12,450 Armenians lived in the center of the town, near the bazaar, the reminder in Nemçeler and Malacılar. “They were concentrated primarily in four quarters bearing the names of their respective churches, Surb Hreshtakapet (Holy Archangel); Surb Karapet (John the Precursor); Surb Lusavorich (Illuminator); and Surb Stepanos (Steven).

All the churches had paired elementary schools for boys and girls, the Aramian-Gayanian, Nersesian Sandukhtian, Rubinian-Hripsimian, and Mesropian-Nunian as well as kindergartens, one of which was named Manushag. In 1909, a central secondary school for boys was opened, and in 1912, a supplementary educational program for girls was initiated. There was also an Evangelical girls’ boarding school called Hayuhiyats. All the quarters had a corresponding neighborhood council. Armenians had their own social organizations such as the educational Krtasirats Association and the literary Entertsasirats Union. They also had their own theatrical group, band, choir, athletic teams, and a women’s benevolent organization. In 1910, the newspaper Erkir (Homeland) was published in Adabazar before being transferred to Constantinople the following year. There was also the weekly newspaper Butania (Bithynia), which was printed by the Atrushan publishing house.”[5]

“Southeast of Adabazar, on the southern shore of Lake Sabanca, the Armenians had, in 1710, founded a village of the same name, which, with its southern ‘New Quarter’ had 360 inhabitants. East of the town, in the nahiye of Handık, were two more Armenian villages, Hayots Kiugh [‘Village of the Armenians’] (pop. 1,007) and Hoviv (pop. 288). A few more Armenians lived scattered in other localities. To the southwest, in the nahiye of Akyazi, the little village of Kup was inhabited by 1,064 Orthodox Armenians, whose ancestors had come from Agn.”[6]

Arrests, Torture, and Deportations during WW1

In summer 1916, the Christian (Greek-Orthodox) population of the villages Low and High Neohori in the Greek Orthodox Diocese of Chalcedonia was deported and distributed among the villages and towns of Tuzla, Adapazarı, Eskişehir and Kütahya.[7]

The eliticide and deportations of the Armenian population of the kaza started earlier than those in Izmit.

“The teacher of the Gregorian school in Adapazarı was beaten to death, another beaten until he went insane. Women were also given the bastinado. Ibrahim Bey boasted that he had authority from the government to do whatever he wanted with the Armenians. To stir up the Mohammedans, the most ridiculous lies were spread. A Turkish officer told that the Armenian women had hidden 10,000 razors with them to cut the necks of the Turks. In Adapazarı, women and girls from well-off circles were also herded into the Armenian church and subjected to interrogation for concealed weapons. When they did not know how to testify, they were violated in the most disgraceful way. A mother threw herself between the policeman and her consumptive son and caught the pranks played on him. A German woman tried to save her Armenian husband. ‘Get out of the way or I’ll hit you,’ the officer shouted, and when she said she was German, he replied, ‘I don’t care about your emperor; my orders come from Talat Bey.’”

Excerpted and translated from: Zurlinden, Samuel: Der Weltkrieg. Vorläufige Orientierung von einem schweizerischen Standpunkt aus. Vol. 1. Zürich: Art. Institut Orell Füssli, 1918

“In early May [1915], some 50 Adabazar notables were taken into custody and deported to Sultaniye (in the vilayet of Konya) and Koçhisar. (…) According to our Armenian source, 600 to 700 men were arrested in the Church of St. Garabed in the space of a few days. The auxiliary primate, Father Mikayel Yeramian, and a notable, Antranig Charkejian, were the first victims of the torture that Ibrahim ordered his men to carry out in order to make the prisoners confess where they had stashed their weapons. Two weeks later, 10 notables were brought before the Istanbul court-martial.

On 11 August 1915, the order to deport the Armenians of Adabazar and the surrounding villages was published. (…) In two weeks, more than 20,000 people, beginning with those who lived in the neighborhoods of Nemçer and Malacılar, were put on the road to Konya. Twenty-five families of craftsmen who worked for the army were spared and allowed to remain in their homes, as was the one family that agreed to convert, that of Haci Hovhannes Yeghiayan.”[8]

“Shortly before the Ottoman entry into World War I, the men of Adabazar were conscripted into the army and placed in labor battalions. The city, however, had a conscientious mayor and garrison commander, giving the population a general feeling of security. But conditions soon deteriorated, as several hundred prominent citizens were imprisoned in one of the Armenian churches and widespread beatings took place, giving way to chaos and hysteria. A report by the German consul general in Constantinople noted that bombs had been uncovered by the police, although the Armenians protested their innocence and said these had been stored in cooperation with the Young Turks during the oppressive reign of Sultan Abdul Hamid II. These raids only served as the prelude to the full-scale deportation of the Adabazar Armenians. They were sent away in freight trains or trucks if they could afford to pay for their passage, while those forced to walk gradually died of dehydration, disease, and starvation. Some women committed suicide; others tried to give their children to the American missionaries, but to little avail.”[9]

Arshag Dickranian (born 1905): https://vhaonline.usc.edu/viewingPage?testimonyID=56511&returnIndex=1

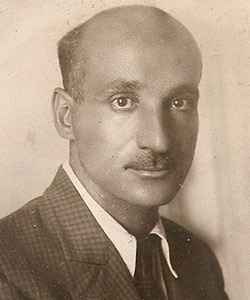

Garegin Abraham Hisheyan (b. 1896, Adapazarı): Survivor’s testimony

“(…) In 1915, Adabazar had a purely Armenian population of 30,000, which had a high cultural-illuminative level, second to Constantinople.

Our family consisted of 8 people (…).

Before the war, they [Turks] collected all the Armenian males and sent them to build roads. The party-activists were sent to the gallows under the pretense of hiding arms. The Armenians had a private bank. In general, trade and medicine were under the control of the Armenians. They had 10 doctors and 4 pharmacies. One daily newspaper was published. They were engaged also in farming, silkworm-breeding and silk-spinning. The Armenians owned three spinning-mills where Armenian women and young girls worked, and manufactured goods were sent to Europe.

The order of the government was to deport all the Armenians. They packed us in cattle-wagons and took us to the small town of Ereğli, near Konya. Before reaching there, they detrained us in the locality called Karaman, so that the Turkish rabble could rob and plunder us, beat us, disgrace and abduct our women and girls, since the right to do anything with the Armenians had been given to every Turk. We then reached Ereğli and later Pozantı, which was at the border to Cilicia at the beginning of the Taurus mountains.

In Ereğli they ordered us to get off the wagons and to rest in the open field or to pitch tents until a new order came. Those who had money moved to the town of Ereğli, those who had no money were obliged to continue on foot to Der-Zor.

In Ereğli Plain it happened that a gendarme on horseback appeared from nowhere and attacked the people sheltered under the tents and massacred them or drove them forcibly, where to? Nobody knew. You had only to go on foot, hungry and thirsty, until you fell down on the road; and thus till Der-Zor. Those, who were able to reach there fell into the clutches of the Kurds and were slain or, if they had some money left, they bribed the murderers and somehow saved their lives. We came back again to our houses in Ereğli, but we hid in the stable. Little by little, I started to work, first as a coachman, then as a baker.

Then I was drafted into the army. They took me to Constantinople, Pozantı, Intilli and later to Damascus, Jerusalem, Aleppo, where I met my paternal uncle and wanted to escape, but they found me. Then I fled again. I reached Adabazar and found my relatives. In 1921, when they definitely drove the Armenians out of Turkey, I went to Rumania, to Constantsa and thence to Hungary, to Budapest. Later I went to Greece, to Salonica, where my relatives had moved. On December 14 1924, we came from Salonica to Soviet Armenia by ship. I have worked with the repatriate sculptor Ara Sargsian. I have engraved on wood and have been honored with diplomas.”

Source: Svazlian, Verjiné (ed.): The Armenian Genocide: Testimonies of the Eyewitness Survivors. Yerevan: “Gitoutyoun” Publishing House of NAS RA, 2011, p. 382 f.

The Annihilation of the Greek Town of Levkes (Lefke)

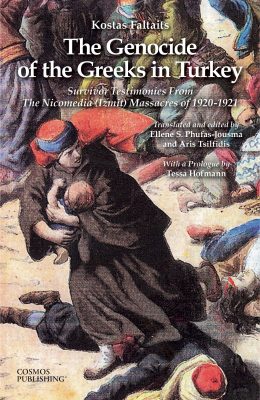

Levke(s) (also Lefke(s), the ‘White(s)’; today Osmaneli) had a Greek Orthodox population of about 5,000, of whom only “forty to fifty survived”.[10] In his event-close published collection of survivors’ recollections, the Smyrna born renowned Greek journalist and author Konstantinos Faltaits (1891-1944) also included the testimony of Eleni Vafiadis, a Greek from Levkes, who survived by hiding, together with other women, in sewers. We thank Cosmos Publishing for the kind permission to reprint the following excerpts from her account:

“The narrative of Eleni Vafiadis is the story of the slaughter of Lefkes (today Osmaneli). I heard it in her own words in May, 1921, in Ada Pazar [Adapazarı] and I will not change it here – just as I did not change the other narratives – anything from the tone and the effect of her words. Eleni Vafiadis began her narration:

‘On the eve of the Feast of the Apostles in 1920, 500 Turkish soldiers and irregulars arrived under the command of Cemal and they entered Lefkes. Some of the populace took off for the mountains and others who did not have time stayed behind. I, along with my husband and child, stayed in our house because we were unable to take the infant with us up into the mountains. Then with their dogs the Kemalists started gathering up the men who had stayed in town and locked them up in a large house. A shadow fell over the land from all the people and the wind filled with their shouts as they were crying and screaming. (…)

It was a widespread slaughter. Turks were killing people with their knives, because using up their bullets saddened them and in the clamor and weeping that rose to the heavens the ouds [lutes] of the Turks and their singing could be heard: ‘What are you screaming about, gavurs? What are you screaming about?’ their shouts could be heard. ‘We will not allow even a spore of the Greeks to survive.’

No Christian dared protest- such was the savagery of the Turks that when you saw them you fell to your knees and your arms fell to your sides, withered. The Turkish women would enter our homes, take our clothes, try them on, admire them and then wear them.

People were shouting: ‘Why are we to blame for the war going on? How are we to blame?’

And the toddlers just starting to talk would grab the feet of the Turks and say:

‘Amtza (Uncle) don’t slaughter us. We’ll become your kids.’

The women would beg:

‘Don’t kill us by torturing us… kill us quickly.’

But the Turks toyed with the women, raping them. They would cut the nipples of their breasts passing them around and playing with them like a komboloi (worr beads), and then would kill the women by torturing them horribly.

In the sewers I was half conscious from the horrible odour. I had in my lap my baby which started to cty and the other women said:

‘He will betray us with his cries.’

Then one woman, Athena Hadzi, took my child from my lap, squeezed its neck tightly, strangled it, and then gave it back to me lifeless.

The Turks came over to the sewer, did their business over us, and said:

‘These are the toilets, nobody could be here.’

We stayed there five days and nights without any food or anything to drink, without any sleep to shut our eyes. I had my dead child in my lap, and I saw the worms starting to eat his little eyes. My body was completely numb that entire time, hunched over as it was, and my eyes had puffed up and were swollen.

We were saying: ‘My God, You who gave us our soul, take it back, don’t let them take it from us.’

And we waited for Greece to come and save us.

For five days and five nights we could hear the screams and the weeping of the dead and the songs and instruments of those who slaughtered them.

Then we heard the town crier again, and he called out: ‘All Christians who are hiding come out because there is no more killing.’

We didn’t believe the crier but we all agreed that it was better that they kill us than to suffer this torture any longer.

We went our and headed to our homes. They were all empty and nothing was left inside. And our town was empty of its people because of five-thousand Christians not more than forty to fifty had survived.

Once the slaughter of the town was over, the Turks rode up into the mountains with their dogs to slaughter all those who had hidden themselves there. Whoever they found they cut off their feet, took out one of their eyes, and left them there like that, and for many days and nights their screaming tore through the air until their souls were spent. Haralambos Sevastou, a man they had found on a mountain with his three daughters, Sophia, Eleni, and Marika, they cut off his two legs to the knees and took out one of his eyes, placed his daughters in his lap, and beheaded them all in this way. Then the Turks went back into the mountains and slaughtered the people

who had their hands and feet cut off and were still alive by cutting them up into small pieces.

Of the forty or fifty remaining people in the town, the Turks came out again and picked out any young and beautiful women they could and took them as their own. (…)

Source: Faltaits, Kostas: The Genocide of the Greeks in Turkey; Survivor Testimonies From The Nicomedia (Izmit) Massacres of 1920-1921. Translated and edited by Ellene S. Phufas-Jousma and Aris Tsilfidis. Cosmos Publishing, 2016, p.81, 86f.

1918-1922: No safe return

“At the end of the war in 1918, a few thousand Armenians repatriated to Adabazar in an attempt to rebuild their lives. They found their homes occupied by Muslim refugees, their property and belongings expropriated, and the non-Muslim silk factories destroyed. In roughly a third of the cases, the Armenian homes were in such a state of disrepair as to render them uninhabitable. British officials reported that a mixed commission, established to assist in the restitution of or compensation for material losses, seems to have achieved a degree of success. But whatever gains that were registered in the immediate postwar period were reversed during the Greek army’s retreat from Anatolia in 1921-22 during the final phase of the Greco-Turkish conflict. The Armenians, now forced to flee before the entry of Mustafa Kemal’s advancing Nationalist army, sought haven in Smyrna (Izmir), Greece, and farther abroad.”[11]

The Economic Factor in Genocide

In peaceful economic competition in trade and commerce, the Turk is inevitably outstripped by the intelligent, industrious and very hard-working Armenians. According to the unanimous testimony of European officials of the Anatolian railways, the Turk is only to be used for the lowest positions. From the switchman upwards, only Armenians and Greeks can be used. That is why the Turk is filled with fierce hatred of the unwelcome competitor. Therefore he wrote on his program: economic liberation! The World War finally offered a good opportunity to carry out this programme thoroughly and completely. It was simply a matter of eliminating the unwelcome competitor, and according to the Turkish way of doing things, this is best done by beating him to death. However, the young Turkish government put a modern coat around the matter; it had the Armenians deported from their homeland. That looked very European. Because of “urgent military necessity”, hundreds of thousands of Armenians, both from the eastern provinces and from Asia Minor and Constantinople, were “evacuated” and sent to Mesopotamia. In some places, we have certain reports of this from Angora and Adabasar, these measures were initiated with a massacre. The rabble was told that the police were “absent” on that and that day, whereupon the unclean elements rushed greedily to the Armenian shops, killing the owners, appropriating the goods and kidnapping the women. Such a method of economic “liberation” was naturally obvious to the people, appealing to their baser instincts.

Source: From the Swiss newspaper “Basler Anzeiger”, June 1918: http://www.armenocide.net/armenocide/armgende.nsf/$$AllDocs/1918-06-29-DE-001