Its name comes from the town of Eskişehir (Tr: ‘old city’), which was called Dorylaion (Gr: Δορύλαιον) in ancient times. Dorylaion, which was mentioned on the occasion of the clash of Lysimaxos and Makedonian satrap and later king Antigonos I, one of the earliest commanders of Alexander the Great (Diodorus Siculus Bibl. H. 20.108), did not preserve its name since it was partially or completely abandoned during the Seljuk conquest in the late twelfth century. Since 1484, the Turkish name Eskişehir is documented.[1]

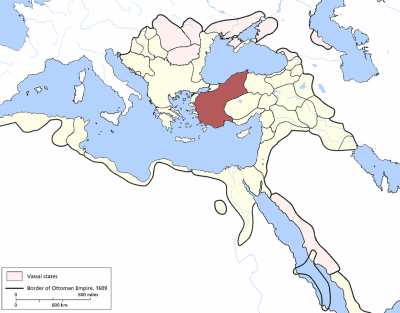

After the Ottoman expansion into the area, the region was made into a sancak in the Anatolia (Tr: Anadolu) Eyalet, then reorganized as a kaza center in the sancak of Kütahya in the 19th century.

Christian Population

At the turn of the 20th century, there were 67,000 people living in the kaza of Eskişehir; of these, slightly more than 6,000 were Armenians, “who had immigrated from nearby Kütahya and Sivrihisar, as well as seasonal itinerant workers (pandukhts) who sought temporary work in the town. The Armenian and Greek quarters of Eskişehir were located at the foot of an imposing hillside. A well-stocked covered market was also found here, next to the town’s famed thermal baths. The Armenian community maintained the Holy Trinity (Surb Errordutiun) Church and the Surb Mesropian and Surb Sandukhtian coeducational school, with an enrollment of 221 pupils at the turn of the twentieth century. In addition, half of the forty students at the French school of the Pères français Saint Augustine de l’Assomption d’Eski-Chèhr were Armenian.

Ahmed Sherif, a Turkish journalist from the Constantinople-based newspaper Tanin (Echo) who traveled to Eskişehir in November 1909, took note of the cleanliness and orderliness of the Armenian school, and expressed surprise to see the graduating class even acting out a mock session of Parliament. Like their Greek coreligionists, the Armenians of Eskişehir made their living from commerce and the crafts. Goat’s hair (tiftik; mohair) and opium were particularly important products of export, as were cereals, apricot kernels, and lumber. All the Armenians were deported in 1915, and the town was completely destroyed in 1922 during the conflict between Greece and Mustafa Kemal’s Nationalist forces.”[2]

“In the Armenian quarter of Eskişehir, founded early in the seventeenth century, there were barely 1,000 Armenians. They worked mainly in the bazaar, which they ran together with Greeks. There were another three Armenian villages in the rest of the kaza, Artaki Çiftlik, Karaharac, and Bey Yayla; the total Armenian population of the district was 4,510. These Armenians were deported on 14 August 1915, under extremely harsh conditions; they were not authorized to take any belongings at all with them. (…) When Father Vartan Karageuzian passed through Eskişehir around 15 October, the city had been entirely emptied of its Armenians, with the exception of a few Catholic families.”[3]

Transit Concentration Camp

Like other cities in the province of Bursa, Eskişehir formed a transit concentration camp for deported Greeks and Armenians in 1915. The chairman of the Baghdad Railway in Constantinople, Franz Johannes Guenther, reported his observations to the German Embassy in Constantinople in October 1915:

“While leaving Haidar-Pasha, I already noticed a very large number of Armenian families who were being led by the gendarmes to the freight trains, where far more people than the designated number for each wagon were loaded in. These people were let out in Ismid and taken to a camp, and in their place other Armenians from that area were loaded in the same fashion.

While leaving Eski-Shehir, I saw that the number of Armenians on the train had grown. Some of the deportees had been loaded onto the two stories of wagons meant for small animals (so-called ‘H wagons’); the roofs of the wagons were also covered with people. They stayed there during the entire journey, even during the night, which was bitterly cold.

Influential people, whom I asked if such occurrences happened often and whether nothing was done about the people who remained on the roofs during the cold nights, explained that they could do nothing to remedy the situation and that this had been a daily phenomenon for weeks.(…)”[4]

Petition of an Armenian to the German Embassy, submitted by Monsignore Cardinal Angelo Dolci, 19 August 1915

To the German Embassy of Constantinople

Pera, 19 August 1915

The deportation of the Armenians

I. Urgent Request

- Contrary to the formal promises that at least the Catholic Armenians would be spared, the Catholic priests and their people from Nicomedia were deported on 11th inst. [August 1915], in the direction of Konia. Two priests and part of the Catholic people remained en route in Eskişehir, but after five days received the order to move on. We beg you to allow the two priests and their people either to return home or to remain in Eskişehir, as free as the Catholics there.

- Contrary to the promises made very recently that the Protestant and Catholic Armenians would be spared, on 16th inst. [August 1915], the entire population of Baktchedjik [Ar: Bardizag; Tr: Bahçecik] – a purely Armenian village opposite to Nicomedia – was deported. Only by chance did the three Catholic priests and five nuns remain behind at the station in Nicomedia. Their people have already all left. We implore you to allow those remaining either to return to Baktchedjik or to Constantinople and the people who have already left to at least stay in Eskischehir if it is not possible for them to return to Baktchedjik.

II. General Notes

The situation for the deportees is very deplorable, in particular the poorer class is suffering terribly. Many mothers throw their children in the rivers to avoid having to see them tormented any longer. Other mothers sell their little ones to be able to buy a piece of bread and to save them from certain death. Children up to the age of 6 years are sold for 5 piasters, that is less than one mark, and the 15- 20 year old girls for 20 piasters. At night in particular, all kinds of disgraceful acts of violence are carried out on the wives and girls.

Eskişehir, Kütahya, Afyon Karahisar und Konia are central places where they are collected in masses outside the towns on an enclosed field, for example near Eskişehir, when 10 – 12000 children, women and old people were turned out into the open and exposed to the unpredictable whims of the people and the weather. A reliable eye witness told how he had seen hundreds of bodies lying on the field in Eskişehir a few days after a thunder-storm, in particular children’s corpses which the Christian railway officials had not allowed to take shelter under the station roof.

Also, the railway officials did not always behave considerately. The people piled up in the fields without any means are whipped three times a day in order that they move on because they cannot travel by train. Nobody knows what happens to the Armenians who are deported on to Konia. God bless those who relieve the suffering of these poor people.“

Source: Petition submitted by an Armenian to the Embassy in Constantinople; Pera, 19 August 1915, Submitted by Monsignore Dolci; Political Archives of the German Foreign Office, http://www.armenocide.net/armenocide/armgende.nsf/$$AllDocs-en/1915-08-19-DE-012?OpenDocument

E. Neuner: Report on a journey inside Turkey (October-December 1917)

“(…) Another significant case is the following: The director of the Ottoman Bank in Eskişehir, a man of Armenian origin but an Austrian protégé, had received in a cassette the assets of a related Armenian for safekeeping when he was forced to leave the city by the Turkish government. The cassette contained securities and jewellery. The Turkish authorities issued a decree prohibiting anyone from taking any Armenian valuables into custody. This bank director wanted to avoid inconvenience and decided to hand over the cassette to the Turkish authorities. He asked some German friends to help him to make a detailed record of the contents of the cassette and prepared a list of the contents, which he had everyone sign and gave to everyone for safekeeping. He then brought the cassette together with a table of contents to the Mutesariff, roughly equivalent to the German President of the Government. After two days, he was ordered to go to the place where the Mutesariff reproached him most vehemently about how he could dare to take the Turkish authorities for fools. He had opened the cassette and found only old junk and two broken revolvers. The two revolvers had obviously been put in there in order to cause the man difficulties because of the ban on carrying weapons. When the bank director replied that this could not be possible, that the cassette must have been looted and filled with this stuff because he had made a precise table of contents in front of witnesses before he delivered it, the Mutesariff shouted at him how he could dare to tell a Turkish authority lies and threw him out. After a few days he was arrested, then had to walk the 420 km distance to Haidar Pasha and after spending a few months there, he was put on trial; there he was sentenced to 6 months in prison, because he did not hand over the cassette to the Committee for the Administration of the Property of the Armenians, but to the Mutesariff. Although he was an Austrian protégé and the whole thing was more than ridiculous, he had to serve these 6 months and of course he lost his position at the bank. One could tell many more examples of this kind, but how things go on down there, one can’t really get a proper idea of it. It’s appalling.”

Source: From a letter of the German War Ministry to the State Secretary of the Foreign Office (Jagow), 22 February 1918. http://www.armenocide.net/armenocide/armgende.nsf/$$AllDocs/1916-10-13-DE-002