Toponym

The district was formerly called Hark’ (Հարք; documented since the year 630). It was a county of the Turuberan province of historical Armenia. The earliest record of Kop’ is found in the 995 encyclical from Vandir monastery under the name Koghb (Կողբ), which was later distorted.

The Turkish name of the kaza, which was in use since the year 1869 relates to Bulanık (‘Blurred’) Creek of the Murat River (Eastern Euphrates; Aradzan in Armenian).[1]

History

After the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, Turkmen tribes (such as Bayat, Eymür and Bayındır) settled in Bulanık. Today, Kurds are the majority. Before the genocide against the Ottoman Armenians, there was an Armenian majority, which was later replaced by Turks (in addition to local Turkmens, Bulanık took a lot of Turkic emigrants such as Meskhetians and Qarapapaq Turks. These Muhacirs‘ first came with the Russo-Turkish War of 1877/8 and continued to immigrate during the Republic era).

Two miles south of the administrative center Kop’/Gop was an Armenian monastery named Surb Daniel which contained the relics of a saint of that name.

Population

As a result of the volatile history and uncertainty, the demographic development of the region was subject to strong fluctuations and frequent emigration. “In the thirteenth through sixteenth centuries, Bulanik was conquered by Tatar-Mongol and Turkmen tribes. Under the terms of the Turko-Persian treaties of 1555 and 1639, the county was included in the Ottoman Empire.

In the early seventeenth century, Shah Abbas I deported thousands of Bulanik Armenians to Persia. A century later, the Bulanik villages were ravaged during a series of renewed Ottoman-Persian wars. During the 1828 – 1829 Russo-Turkish war, hundreds of Bulanik Armenians, fearing an outbreak of Kurdish violence, followed the Russian retreat and settled in eastern Armenia. Almost completely deserted, the Bulanik villages were repopulated by Armenian settlers from the neighboring counties. A number of former residents of Khlat (Ahlat), Hizan, Mokats (Moks) and Arjesh moved to the villages in the eastern part of Upper Bulanik, while groups of former residents of Bsherik, Sasun, Khout, Motkan and Taron resettled in the villages in the western part of Upper Bulanik and in almost all the villages of Lower Bulanik.”[2]

The census carried out by the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople prior to World War I produced a figure of 25,053 for the Armenian population in the kaza Bulanık, residing in 30 localities and maintaining 29 churches, three monasteries and 14 schools for 575 students.[3]

At the end of the 19th century H.F.B. Lynch described the administrative center Kop’ as a large village with about 400 houses, all but 50 of them inhabited by Armenians. Although the soil was amongst the most fertile in the region, he found the inhabitants almost destitute due to the region’s insecurity and the impossibility of exporting their crops. Historically, Bulanık was known for producing wheat and salt.

Henry Finis Blosse Lynch: Fertile soil, but destitute peasants: Kop / Gop and Liz

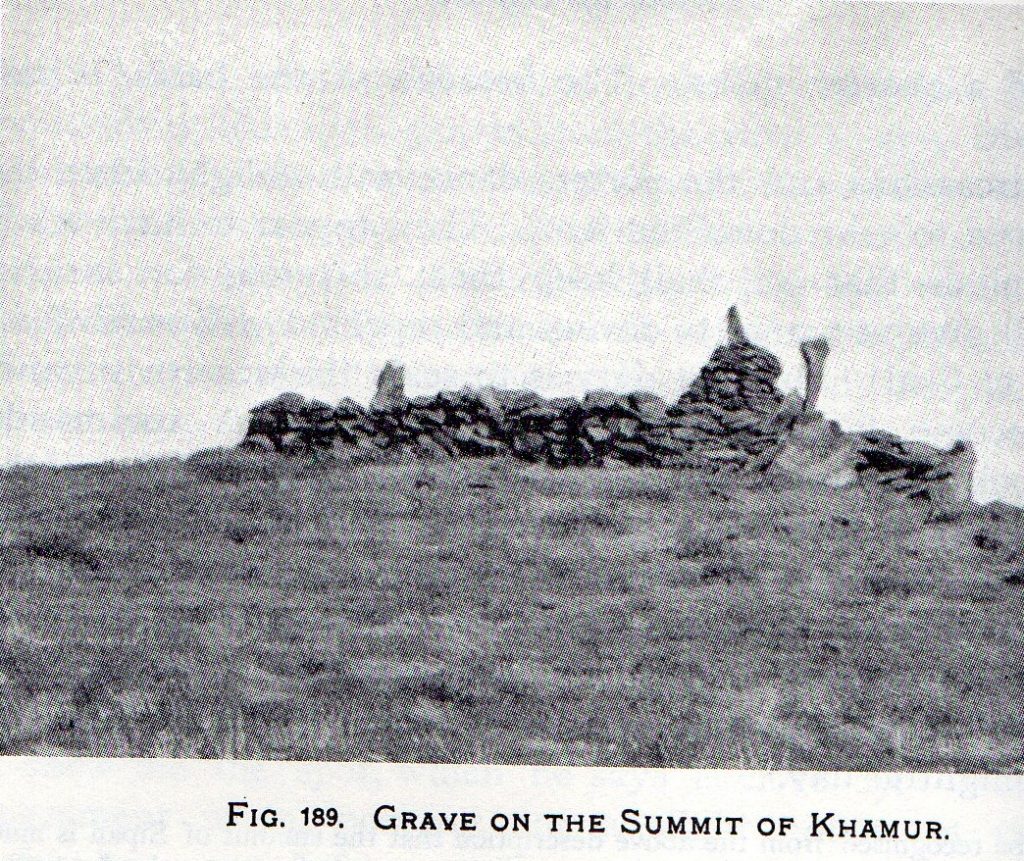

“Gop is situated in the plain, some miles distant from the lake, at the foot of the extreme slopes of the heights which border the northerly shore (alt. 5150 feet). Although the place is the capital of the caza of Bulanik, it is a large village rather than a town. The Kaimakam informed me that there were 400 houses, all but 50 inhabited by Armenians. The district of Bulanik comprises some of the most fertile land in all Armenia, and is of considerable area. Towards the east it includes a large portion of the plain of the Murad below the town of Melazkert [Malazgirt; Manaskert; Mantsikert]; while on the west, it reaches across the mass of Bilejan and its outliers to a second extensive stretch of fairly level ground. That region slopes away from the norther border heights of Mush plain to the Murad and the opposite heights of Khamur; it sends a tributary to the left bank of the great river, and one of its principal and central villages is that of Liz. The fecundity of the soil is probably due to a happy combination of calcareous marls with the detritus of eruptive rocks. The grain which it produces is of excellent quality, in spite of the fact that the fields will be full of thistles. The peasants are miserably poor. The Kaimakam explained that their rags and squalor were matter of custom (tabiat); and, in fact, they had plenty of money, hoarded away. It is possible that such a hypothesis may indeed govern some of his actions; but I doubt whether he put it forward in good faith. The main cause of their destitution is plainly the want of security, coupled with the impossibility of exporting their crops. But usury is also a factor of considerable importance, the husbandman having generally borrowed to buy his seed at rates which rob him of most of the earnings of his toil.”

“Gop is situated in the plain, some miles distant from the lake, at the foot of the extreme slopes of the heights which border the northerly shore (alt. 5150 feet). Although the place is the capital of the caza of Bulanik, it is a large village rather than a town. The Kaimakam informed me that there were 400 houses, all but 50 inhabited by Armenians. The district of Bulanik comprises some of the most fertile land in all Armenia, and is of considerable area. Towards the east it includes a large portion of the plain of the Murad below the town of Melazkert [Malazgirt; Manaskert; Mantsikert]; while on the west, it reaches across the mass of Bilejan and its outliers to a second extensive stretch of fairly level ground. That region slopes away from the norther border heights of Mush plain to the Murad and the opposite heights of Khamur; it sends a tributary to the left bank of the great river, and one of its principal and central villages is that of Liz. The fecundity of the soil is probably due to a happy combination of calcareous marls with the detritus of eruptive rocks. The grain which it produces is of excellent quality, in spite of the fact that the fields will be full of thistles. The peasants are miserably poor. The Kaimakam explained that their rags and squalor were matter of custom (tabiat); and, in fact, they had plenty of money, hoarded away. It is possible that such a hypothesis may indeed govern some of his actions; but I doubt whether he put it forward in good faith. The main cause of their destitution is plainly the want of security, coupled with the impossibility of exporting their crops. But usury is also a factor of considerable importance, the husbandman having generally borrowed to buy his seed at rates which rob him of most of the earnings of his toil.”

Quoted from: Lynch, H.F.B.: Armenia: Travels and Studies. Vol. Two: The Turkish Provinces. (Reprint). Beirut: Khayats, Third edition, 1990, p. 344f.

Tigran Martirosyan: Demography of the kaza of Bulanık

“Along with the Manazkert, Vardo, Moush and Sassoun counties, the kaza (county) of Bulanik formed the Moush sancak (prefecture) of the vilayet (province) of Bitlis and was one of the most densely Armenian-populated counties, not only in the Bitlis province, but in all of the Armenian Highlands in the decades before the genocide; this view is substantiated by several contemporaries. (…)

It is at once apparent that Armenian sources are more detailed and offer more plausible figures than Ottoman sources, which have been often accused of decreasing Armenian population numbers. In 1880, the Patriarch of Constantinople, Nerses Varzhapetian, initiated a census of Bulanik, Manazkert and Moush, which revealed that the population of Armenians was at 225,000 and the population of Muslims at 55,000. Once these numbers were revealed, local Ottoman authorities in Moush pressured municipal council member Karapet Efendi Potikian to lean on other members to compel them to decrease the Armenian figure to 95,000 and inflate the Muslim one to 105,000. Ottoman sources containing statistical data on the Armenian population of Bulanik are government annuals for the state and provinces, called salnamés. For instance, the 1871 salnamé for the vilayet of Erzurum states there were 3,835 Armenian and 1,341 Muslim men in the county. The 1872 salnamé states there were 4,025 Armenian and 1,441 Muslim men. Yet another, from 1873 lists 4,361 Armenian and 3,892 Muslim men living in 2,049 total households. The 1892 salnamé for the vilayet of Bitlis stands out in that it offers concrete evidence that Armenians were the majority in Bulanik: of 25,456 inhabitants, 8,567 were Muslim, while 16,889 were Armenian; thus, Armenians constituted 66.3% or two-thirds of the total population of the county.

Ottoman government censuses also contain statistics on the Armenian population in the region. A census carried out by the Patriarchate prior to World War I produced a figure of 25,053 for the Armenian population in Bulanik; the Ottoman census placed the number of the Armenian population at 14,662. Significantly, according to Karo Sassouni’s count, the number of Armenians of Bulanik and Manazkert who found refuge in Russian Transcaucasia in July 1915 was estimated to be 34,000. Using solely the pre-WWI Patriarchate figures of 25,053 for Bulanik and 11,931 for Manazkert, the number of Armenians in both counties would be a total of 36,984.

On the other hand, if only using Ottoman data for both counties (14,662 and 4,438 for Bulanik and Manazkert, respectively) the number of Armenians would be a total of 19,100. Another Ottoman source indicated that in 1915, the number of Bulanik Armenians who were to be forcibly deported, or as Turkish sources put it, ‘relocated and distanced,‘ was recorded in their registries at 14,309. Interestingly, an Armenian accusatory report published in 1918 in Aleppo put the number of survivors from Bulanik and Manazkert at about 25,000.

Although a report signed by a group of genocide survivors carries less strength than a census or a count, the figure for the two counties contained in it is still 1.3 times larger than the Ottoman figure of 19,100, while the Armenian figure of 25,053 for Bulanik alone is 1.7 times larger than the Ottoman figure of 14,309 for the same county. Given that most Armenians of Bulanik and Manazkert escaped massacres thanks to the advance of the Russian troops into the region in May of 1915, it can be said that the Patriarchate figure seems to be fairly accurately reported. (…)”

Excerpted from: Tigran Martirosyan: Kaza of Bulanik – Demography. “Hetq”, 6 May 2017, https://hetq.am/en/article/78522; read more: https://www.houshamadyan.org/en/mapottomanempire/vilayet-of-bitlispaghesh/kaza-of-bulanik/locale/demography.html

Destruction

Flight and massacres in May 1915

“(…) Thanks to the rapid advance of the Russian forces into the region in May 1915, the population of the villages in Upper Bulanik escaped massacre. (…)

The villagers of the 11 localities in Lower Bulanik, which lay much further southwest – Liz (pop. 1,499), Kerolan, Abri (pop. 203), Khoshkaldi (pop. 10,018), Adghon (pop. 754), Prkashen (pop. 517), Goghap (pop. 472), Akrag (pop. 267), Mulakend (pop. 200), and Pionk (pop. 457) – were less fortunate. Khoshkaldi came under attack by Kurds commanded by Musa Kasim [Kazım] Beg, the leader of the Jibran tribe, Haydar, and a well-known bandit, Jendi. The Kurds first massacred the males over five, and then turned to the women. As for the members of the 60 households in Kerolan, they were massacred by Kurds under the command of local Kurdish sheikhs, with the exception of a few young women and girls who were carried off to Liz by their torturers.

Some of the villagers of Abri, Adghon, Prkashen, Goghag, Akrag and Mulakerd were massacred in their villages around 10 May by Seykh Hazret and Musa Kasim. The survivors, after trying in vain to cross the Turkish lines, fled to Liz, the principle town in the nahie, were the commander of the local garrison protected them until 18 May, the day Russian troops arrived in Upper Bulanik. At that point, 1,200 men were put in chains and shot one verst (1,066 km) from Liz; their bodies were dumped into two immense mass graves by regular troops.”

Excerpted from: Raymond Kévorkian: The Armenian Genocide: A Complete History. London, New York: I.B. Tauris, 2011, p. 350f.