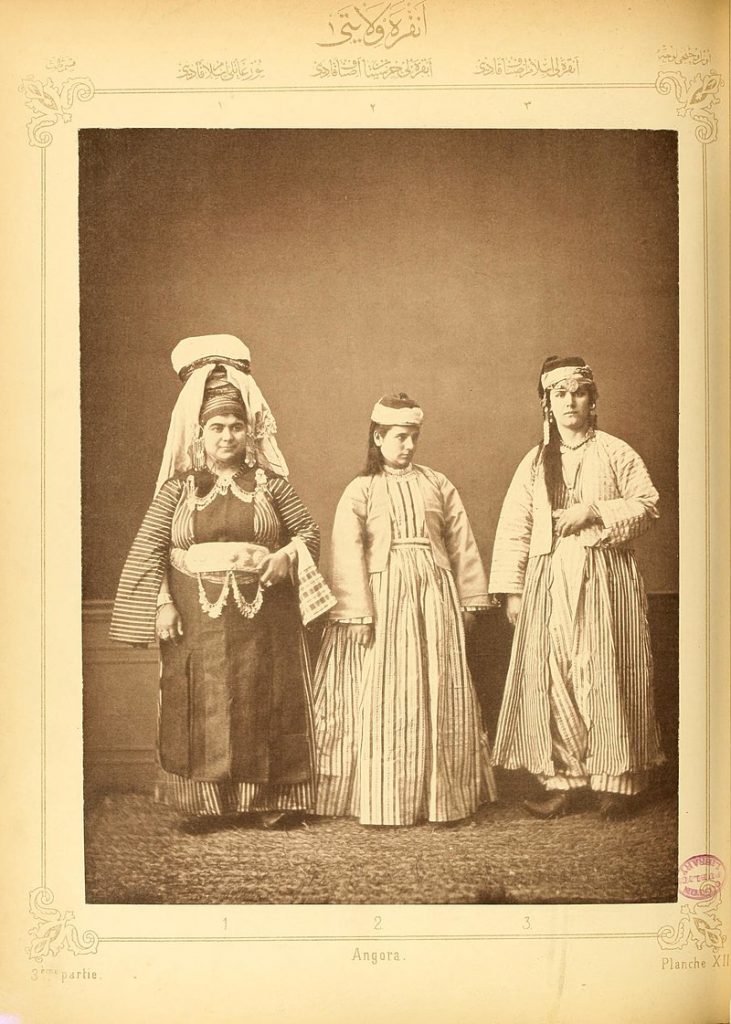

The province of Angora was strongly agricultural, depending on the prosperity of its grain and wool production and mohair – obtained from the Angora goat. Another important industry was carpet weaving in Kırşehir and Kayseri. There were mines for silver, copper, lignite and salt.

Toponym

The current toponym derives from Greek ‘ Ἄγκυρα – Ánkyra’ (anchor). On 13 October 1923, the provincial capital – now the capital of the Republic of Turkey – was officially renamed Ankara.

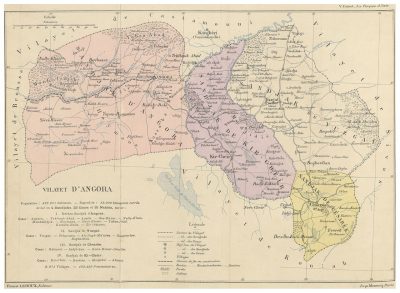

Administration

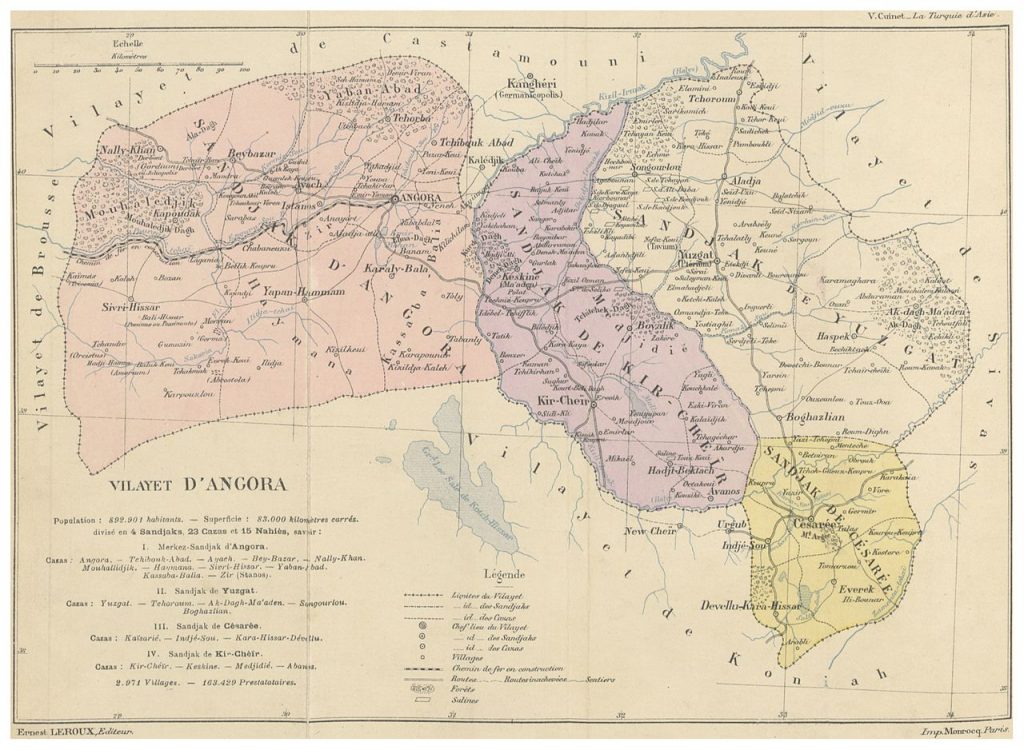

The province of Ankara (Angora), created in 1864, consisted of the four sancaks of Ankara, Kırşehir, Kayseri and Yozgat and 23 kazas. In the late 19th century, the province comprised a territory of 83,700 km2.[1]

From 1867 to 1922, the city of Ankara served as the capital of the Angora Vilayet, which included most of ancient Galatia.

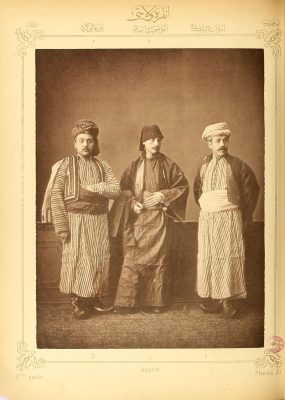

Population

“The Vilayet Angora counts 95,000 Armenians among 892,000 inhabitants according to Turkish statistics. The city of Angora is a headquarters of Catholic Armenians, who number 15,000 souls here and in the surrounding area.”[2]

Based on the statistics of the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople, Raymond Kévorkian cites slightly higher population figures: “The sprawling densely populated vilayet of Angora had, in 1914, an Armenian population of 105,169. They lived in 88 towns and villages, and had 105 churches, 11 monasteries, and 126 schools with a total enrollment of 21,298. Although there had been long an Armenian population in the sancak of Angora, it was now concentrated in a few urban centers – in Angora, of course, but also in Kalecik, Stanoz, Nallihan [Nallıhan], Muhalic, and Sivrihisar. The sancaks of Yozgat and Kayseri, in contrast, had a non-negligible rural Armenian population that went back to the Middle Ages.”[3]–

In addition, according to Ottoman statistics, there were about 20,240 Cappadocian Greeks living in Ankara province.[4] The Greek Orthodox Diocese of Angora[5] comprised seven communities with a population of 10,598.[6]

History

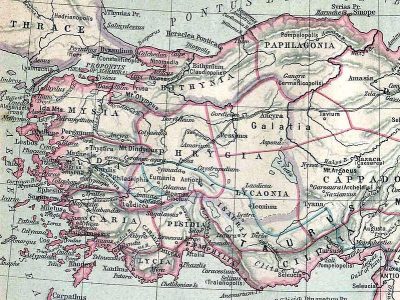

The history of the region begins with the pre-Bronze Age civilizations. The Hittites followed in the 2nd millennium B.C., in the 10th century B.C. the Phrygians, then the Lydians, Persians, Greeks, Galatians (Celts), Romans, Byzantines and Turks (the Seljuk Sultanate of Rome, the Ottoman Empire, and

finally the Republic of Turkey).

Ancient history

The oldest settlements in and around the city center of Ankara belonged to the Hattic civilization which existed during the Bronze Age and was gradually absorbed c. 2000 – 1700 B.C. by the Indo-European Hittites. The city grew significantly in size and importance under the Phrygians starting around 1000 B.C., and experienced a large expansion following the mass migration from Gordion, (the capital of Phrygia), after an earthquake which severely damaged that city around that time. In Phrygian tradition, King Midas was venerated as the founder of Ancyra, but Pausanias mentions that the city was actually far older, which

accords with present archeological knowledge.

Phrygian rule was succeeded first by Lydian and later by Persian rule, though the strongly Phrygian character of the peasantry remained, as evidenced by the gravestones of the much later Roman period. Persian sovereignity lasted until the Persians’ defeat at the hands of Alexander the Great who conquered the city in 333 B.C. Alexander came from Gordion to Ankara and stayed in the city for a short period. After his death at Babylon in 323 BC and the subsequent division of his empire among his generals, Ankara, and its environs fell into the share of Antigonus.

Another important expansion took place under the Greeks of Pontos who came there around 300 B.C. and developed the city as a trading center for the commerce of goods between the Black Sea ports and Crimea to the north; Assyria, Cyprus, and Lebanon to the south; and Georgia, Armenia and Persia to the east.

Celtic era

In 278 B.C., the city, along with the rest of central Anatolia, was occupied by a Celtic group, the Galatians, who were the first to make Ankara one of their main tribal centers, the headquarters of the Tectosages tribe. The Celtic element was probably relatively small in numbers; a warrior aristocracy which ruled over Phrygian-speaking peasants. However, the Celtic language continued to be spoken in Galatia for many centuries. At the end of the 4th century, St. Jerome, a native of Dalmatia, observed that the language spoken around Ankara was very similar to that being spoken in the northwest of the Roman world near Trier.

Roman era

Ancyra was the capital of the Celtic kingdom of Galatia, and later of the Roman province with the same name, after its conquest by Augustus in 25 B.C., who raised Ancyra to the status of a polis and made it the capital city of the Roman province of Galatia. Two other Galatian tribal centers, Tavium near Yozgat, and Pessinus (Ballıhisar) to the west, near Sivrihisar, continued to be reasonably important settlements in the Roman period.

During the 3rd century A.D., life in Ancyra, as in other Anatolian towns, seems to have become somewhat militarized in response to the invasions and instability of the town.

Byzantine era

The city is well known during the 4th century as a center of Christian activity, due to frequent imperial visits, and through the letters of the pagan scholar Libanius. Bishop Marcellus of Ancyra and Basil of Ancyra were active in the theological controversies of their day, and the city was the site of no less than three church synods in 314, 358 and 375, the latter two in favor of Arianism.

When the province of Galatia was divided sometime in 396/99, Ancyra remained the civil capital of Galatia I, as well as its ecclesiastical center (metropolitan see).

In 620 or more likely 622, Ancyra was captured by the Sassanid Persians during the Byzantine–Sassanid War of 602–628. In 654, the city was captured for the first time by the Arabs of the Rashidun Caliphate, under Muawiyah, the future founder of the Umayyad Caliphate. At about the same time, the themes were established in Anatolia, and Ancyra became capital of the Opsician Theme, which was the largest and most important theme until it was split up under Emperor Constantine V (r. 741–775); Ancyra then became the capital of the new Bucellarian Theme.

Märtyrs and Metropolis: Ecclesiastical history

Early Christian martyrs of Ancyra, about whom little is known, included Proklos and Hilarios who were natives of the otherwise unknown nearby village of Kallippi, and suffered repression under the emperor Trajan (98–117). In the 280s we hear of Philumenos, a Christian corn merchant from southern Anatolia, being captured and martyred in Ankara, and of Eustathius.

As in other Roman towns, the reign of Diocletian marked the culmination of the persecution of the Christians. In 303, Ancyra was one of the towns where the co-emperors Diocletian and his deputy Galerius launched their anti-Christian persecution. In Ancyra, their first target was the 38-year-old Bishop Clement, who was taken to Rome, then sent back, and forced to undergo many interrogations and hardship before he, and his brother, and various companions were put to death. Four years later, a doctor of the town named Plato and his brother Antiochus also became celebrated martyrs under Galerius. Theodotus of Ancyra is also venerated as a saint.

However, the persecution proved unsuccessful and in 314 Ancyra was the center of an important council of the early church; its 25 disciplinary canons constitute one of the most important documents in the early history of the administration of the Sacrament of Penance. The synod also considered ecclesiastical policy for the reconstruction of the Christian Church after the persecutions, and in particular the treatment of lapsi—Christians who had given in to forced paganism (sacrifices) to avoid martyrdom during these persecutions.

Though paganism was probably tottering in Ancyra in Clement’s day, it may still have been the majority religion. Twenty years later, Christianity and monotheism had taken its place. Ancyra quickly turned into a Christian city, with a life dominated by monks and priests and theological disputes. The town council or senate gave way to the bishop as the main local figurehead. During the middle of the 4th century, Ancyra was involved in the complex theological disputes over the nature of Christ, and a form of Arianism seems to have originated there.

The Metropolis of Ancyra continued to be a residential see of the Eastern Orthodox Church until the 20th century, with about 40,000 faithful, mostly Turkish-speaking, but that situation ended as a result of the 1923 Convention Concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations. The earlier genocide against the Ottoman Armenians put an end to the residential eparchy of Ancyra of the Armenian Catholic Church, which had been established in 1850. It is also a titular metropolis of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople.

Armenian Catholic Diocese

In 1735 the Armenian Catholic Diocese was established. After being idle for some time, it was restored on April 30, 1850. The Armenian Genocide had its effects on the activities of the diocese, which was discontinued in 1972 and classified as titular see. This diocese had only one leader: Nerses Mikael Setian (3 July 1981 – 9 September 2002) – Emeritus of the Exarchate of the Armenian Apostolic Church in Canada (July 3, 1981 – September 18, 1993).[7]

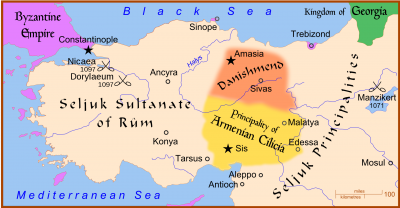

Seljuk, Ottoman and Turkish Republican Era

After the Battle of Man(t)zikert in 1071, the Seljuk Turks overran much of Anatolia. By 1073, the Turkish settlers had reached the vicinity of Ancyra, and the city was captured shortly after, at the latest by the time of the rebellion of Nikephoros Melissenos in 1081. In 1101, when the Crusade under Raymond IV of Toulouse arrived, the city had been under Danishmend control for some time. The Crusaders captured the city, and handed it over to the Byzantine emperor Alexios I Komnenos (c. 1081–1118). However, Byzantine rule did not last long, and the city was captured by the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum at some unknown point; in 1127, it returned to Danishmend control until 1143, when the Seljuks of Rum retook it.

After the Battle of Köse Dağ in 1243, in which the Mongols defeated the Seljuks, most of Anatolia became part of the dominion of the Mongols. Taking advantage of Seljuk decline, a semi-religious cast of craftsmen and trade people named Ahiler chose Angora as their independent city-state in 1290. Orhan I, the second Bey of the Ottoman Empire, captured the city in 1356. Timur defeated Bayezid I at the Battle of Ankara in 1402 and took the city, but in 1403 Angora was again under Ottoman control.

Following the Ottoman defeat in World War I, the Ottoman capital Constantinople and much of Anatolia was occupied by the Allies. In response, the leader of the Turkish nationalist movement, Mustafa Kemal, established the headquarters of his resistance movement in Angora in 1920. After the Turkish War of Independence was won and the Treaty of Sèvres was superseded by the Treaty of Lausanne (1923), the Turkish nationalists replaced the Ottoman Empire with the Republic of Turkey on 29 October 1923. A few days earlier, Angora had officially replaced Constantinople as the new Turkish capital city, on 13 October 1923.

After moving his headquarters to Ankara, Kemal blamed the Armenians and Greeks for the wartime massacres and deportations, while never actually defining what had happened: “Whatever has befallen the non-Muslim elements living in our country is the result of the policies of separatism they pursued in a savage manner, when they allowed themselves to be made tools of foreign intrigues and abused their privileges.”[8]

Destruction

The Minister of Post and Telegraphs decreed on 23 May 1915 that all Armenian employees of the Post and Telegraph Services in the provinces of Erzurum, Ankara, Adana, Sivas, Diyarbekir, and Van be removed from their offices.[9]

“Hasan Mazhar Bey, the vali of Ankara, was one of several in western Anatolia who opposed the CUP’s campaign. The party suspected as much. Considered a sentimental relic of the ancien regime, Mazhar was kept out of Constantinople’s decision-making. He had his first inkling of the deportation plan on April 25, 1915, when he was informed that 180 alleged Armenian komitecis—members of revolutionary committees—would be passing through and that another hundred had been sent to the nearby town of Çankiri. He was ordered to provide men to assist the guard detail.

Mazhar stalled. ‘I pretended not to understand,’ he testified several years later. ‘As you know, other provinces were done with the deportations before I had even started.’ Rather than begin deportations, he decided to investigate the government’s allegation that Ankara’s Armenians were engaged in mass treason. Finding no evidence, he asked Muslim notables to sign a petition to this effect and sent it to the Interior Ministry. By July the government had lost patience with Mazhar’s delays. Talât sent to Ankara a new police chief and deputy governor, Atif Bey, a young and zealous CUP apparatchik. His job was to carry out the deportation, no matter Mazhar’s wishes.”[10]

After having Hasan Mazhar dismissed, the interim Governor, Atıf Bey, a member of the Young Turk Central Committee, had 1,200 non-Catholic Armenian notables of Ankara arrested on 15-20 July 1915. On 14 August, around midnight, several hundred Armenians were escorted by the police and the Gendarmerie, bound in pairs, to the outskirts of the town. The escorts turned them over to the bandits, who were waiting for them in an isolated spot. These recruits of the Special Organization were the butchers and tanners of Ankara, who were “specially remunerated” for executing these men with the help of villagers from nearby areas.[11]

On 27 August 1915, gendarmes and police raided the Armenian quarters and summer homes and proceeded to arrest some 1,500 male Catholics, including the bishop and seventeen priests, who are gathered together in the town. On the night of 29 August, they were set en route to the village of Karagedik, where they are supposed to be executed, but were actually deported along with the rest of the Armenian population via Kirşehir, Kayseri, and Biga, to Aleppo, upon the intervention of Angelo Maria Dolci, the Roman apostolic delegate and ambassador from Austria-Hungary, Pallavicini; only just over 200 people, including the bishop, arrived at Aleppo. Sent then to Ras ul-Ayn or Deir ez-Zor, four priests and some thirty lay-people arrive at the Meskene camp.[12]

“As in other vilayets, Armenian Catholics and Protestants were initially spared on orders from the central government. But this exemption, requested by foreign ambassadors, was rapidly discarded in secret. Most of Ankara’s Catholics and Protestants were eventually deported, and many were killed along the route. According to Richard Lichtheim, Die Welt’s correspondent in Constantinople, among Catholic and Protestant males, ‘only boys under five were permitted to live and all of them were circumcised. Women and girls were made Moslems and distributed.’

A Catholic priest from Ankara later told British officials: ‘After our departure, all our churches, convents, schools, houses and shops were first pillaged and afterwards, burnt down; so that, of a Christian community dating back to the time of St. Paul, there remains not a trace save heaps of cinders. . . . Of 18 Priests who left with me only seven are left, all the others died on the road either of hardship or by violent death.’”[13]

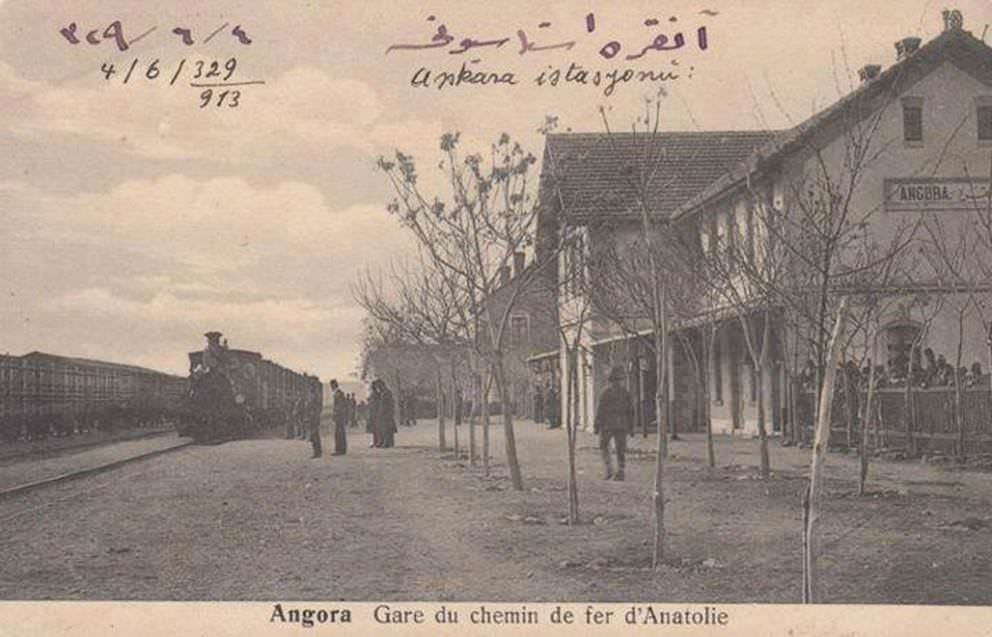

In early September 1915 the women, children, and elderly of Ankara, Catholics and apostolics combined, were expulsed from their homes after they were raided by police. Several thousand people were then gathered at the station, where they remained for 25 days, before being deported to Syria via Eskişehir and Konya.[14]

In a letter dated 17 March 1918, the German Catholic military pastor Dr. David informed that the deputy corps commander, Colonel Osman Bey, intended to deport all Christians from the province of Ankara: 2,000 Greeks, 3,000 Catholics and several hundred Protestant and Armenian Apostolic Christians are to be deported to the interior and distributed in Muslim villages. However, the measure has so far failed due to the energetic resistance of the provincial governor.[15]

On 23 November 1918 a commission of inquiry from the administration was set up by the sultan at the heart of the General Security and was presided over by Hasan Mazhar Bey, the former Governor of Ankara. It undertook the collection of eye-witnesses accounts and concentrated its investigations in particular on the civil servants of the State implicated in crimes committed against Armenian populations. In three months, it compiled three hundred files, which were progressively transmitted to the military tribunal.[16] A year later, in the end of December 1919, 2,500 Armenian escapees were found in the sancak of Kirşehir, 3,000 in the sancak of Yozgat and 4,000 in the sancak of Ankara.[17]

Persecution and Deportation of Orthodox Greeks 1916-1922

“Although this Diocese (comprising seven communities, with a population of 10,598 inhabitants) did not suffer from expulsions or deportations, it was ever since 1914 subjected to a severe boycott, which brought about the great economic crisis, notably at Kutaya and Eski-Shehir [Eskişehir]. This boycott grew in intensity and violence on the arrival at Kutahia of the Minister of War, Enver Pasha (20 June, 1914). It was accompanied this time by threats, printed in Greek and thrown into the houses and shops, to the effect that the infidels would be completely exterminated.

The hatred manifested towards the Christians was of the highest. Even the Minister of the Interior, Talaat himself, showed his spiteful feelings on being told at the Railway Station of Haimana-Angora that Christian names were still to be heard of in that locality. He remarked that ‘only the names of Ali and Mehmet should be heard in future.’

Mobilization greatly contributed to accentuate the economic sad condition of the Diocese. The town of Angora suffered especially from the terrible fire that broke out in August, 1916, during which, owing to the wanton negligence of the Vali, Dr. Rechid [Reşid] Bey, the Greek quarters, comprising the most beautiful section of the town, was reduced to cinders.”(18)

Under date of the 15th March 1917, the Greek Orthodox Metropolitan of Ankara wrote:

“My latest information regarding the fate of the exiled is distressing. The conditions under which the inhabitants of our villages have been expelled are made known to you in my previous reports. After the houses were burnt down, and the plundering of their wealth and furniture had been affected, they went away penniless and deprived of everything. The Turkish villages, in which they are penned up like cattle, are poor, and the inhabitants will not consent to give anything to the ghiavours (infidels). On the other hand, the Government have not taken any care of them, so that the programme of extermination succeeds marvelously. Now, on the basis of good and positive information, I inform you that two-thirds of the Christians expelled have perished in the Turkish villages of Angora. The remaining third are rapidly following the rest. The same fate applies to the Christians in the vilayet of Sivas, who had been expelled from the regions of Tripoli, Kerassounde [Kerasunta; Giresun], Sinope, and Ineboli, to the vilayet of Castambol. It is impossible for me to describe the tortures to which these unfortunate people have been exposed, only because they are Christians and Greeks, during the days of expulsion. I should possibly be accused of exaggerating were I to relate only part of the atrocities committed, such as the abduction of young girls and the massacre of women and children, especially around Erekli, Kourou-keudje, etc.”[19]

The Ankara Province served as a deportation destination for Ottoman Greeks: Between 1916 and 1921, at least eleven deportations of Greek Orthodox Christians from the Pontos area and sancak Kütahya to Ankara province took place.[20] The first deportations occurred in late 1916 to early 1917. A report by the Greek legation at Constantinople dated 27 December 1916 stated how the city of Samsun was encircled by the Turkish army and people were ordered to the city center. “These people (including women, men and women who had just given birth to babies and the babies themselves) were imprisoned in barracks. They were then led out to snow covered mountains. Following the deportations, the homes of the deportees were raided and their belongings taken and sold. While the final destination was unknown, the deportees were seen in Kavak (47 km from Samsun) on the first night where they buried their dead. They were then taken to Kafzan [Havza] in the district of Sivas (80 km from Samsun), then to Çorum (168 km from Samsun).

The deportation resumed on January 17 and 18 [1917] and this time included Greeks from Bafra. As of the 15th of January, 28 villages had been burned excluding those from December. Deportation of women and children by foot and in the midst of rain and snow continued from Samsun to the provinces of Angora and Sivas. The sick and the old were pushed from place to place many sleeping out in the cold naked. Many died of starvation and disease. The number deported was estimated at 20,000. The Greeks of Giresun were also deported during this period.

The two main perpetrators of the deportations and the burning of villages in Samsun were Rafet Pasha and Vehaedin. Vehaedin was a special official of the Ministry of the Interior. He had arrived in the Samsun district around the time of the deportations from Constantinople. He was responsible for preparing the lists of the persons to be deported. Rafet Pasha was a member of the CUP and an emissary of the Ministry of War. He was described as being fanatic, passionate and a hater of Greeks. He was responsible for carrying out the deportations and also arson.”[21]

In late 1919 or 1920 Greek Orthodox notables and elders of Ankara were taken to a nearby location and massacred.[22]

The American Relief worker Alfred E. Brady stated in his event-near published recollections of 1922: “Although the majority of Greek and Armenian civilian men in Asia Minor have been deported to Angora [Ankara], into what is tantamount to slavery, and the majority of women and children exiled, the Turks’ campaign of massacre and terror continues as the last surviving Christian communities are being wiped out one by one.”[23]