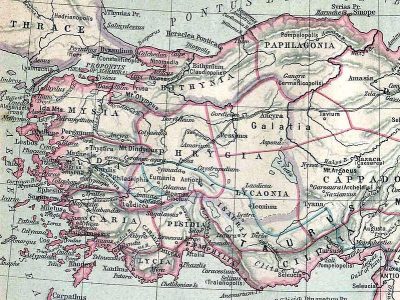

Toponym

Kütahya (ancient Gr: Κοτυάειον Kotyaion, Kotiaeion or Κοτύαιον Kotiaion, Latin: Cotyaeium, Cotyaeum and Cotyaium; also: Kutina, Ketaia, Kyotahya); meaning “the City of the (god) Kotys”, the Greek place-name goes back to native Anatolian, perhaps the Phrygian language.

Phrygia

Phrygia is an ancient region in central Asia Minor, mentioned in the New Testament of the Bible primarily from the travels of the Apostle Paul. The Phrygians, who settled here c.1200 B.C., came from the Balkans and spoke an Indo-European language, apparently similar to Greek, which was used until the 6th century B.C. and written with Greek letters. It shows no similarity with other Anatolian languages. But Herodotos believed that Phrygian colonists founded the Armenian nation.

A kingdom, associated in Greek legend with the names of Midas and Gordios (Gordias, according to Herodotos), flourished from the 8th to the 6th century B.C., when it fell with the Cimmerian invasion (676–585 B.C.) and became dominated by Lydia. Phrygia was best known to the Greeks as a source of slaves and as a center of the cult of Cybele. With the invasions of the Gauls (3rd century B.C.), the north of Phrygia became part of Galatia. The kings of Pergamon ruled much of Phrygia until it passed to the Romans in 133 B.C.

For purposes of provincial administration, the Romans maintained a divided Phrygia, attaching the northeastern part to the province of Galatia and the western portion to the province of Asia. About 295, during the reforms of Diocletian two new provinces were formed, Phrygia Prima (Pacatiana), and Phrygia Secunda (Salutaris), both under the Diocese of Asia. Salutaris with Synnada as its capital comprised the eastern portion of the region and Pacatiana with Laodicea on the Lycus as capital of the western portion. The region in the Northeast of Asia Minor, which corresponds to Kütahya, Afyon and Uşak districts, formed the Phrygia Pacatiana province (provincia)[1] in the Roman administrative division since the 3rd century.

The Roman provinces survived up to the end of the 7th century, when they were replaced by the Byzantine Theme system. In the Late Roman ‘Byzantine’ period, most of Phrygia belonged to the Anatolic theme.

Phrygian soldiers. Detail from a reconstruction of a Phrygian building at Pararli, Turkey, 7th–6th centuries B.C. (source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Phrygian_soldiers._Detail_from_a_reconstruction_of_a_Phrygian_building_at_Pararli,_Turkey,_7th%E2%80%936th_Centuries_BC.jpg)

Aesop – A Phrygian Storyteller?

According to the Suda (Byzantine Gr: ἡ Σοῦδα hē Soûda, ‘the bulwark’), the most comprehensive preserved Byzantine encyclopedia (around 970), Kütahya was the homeland of the ancient Greek poet of fables and parables, Aisopos (Aesop), who probably lived in the 6th century B.C. According to Herodotos († around 424 B.C.) Aesop was a poet, a slave of the Iadmon of Samos, and was killed in Delphi. Aristophanes mentions in the Wasps (first performed in 422 B.C.) that Aesop was accused in Delphi of stealing a sacred object. According to Plutarch († around 125 A.D.), Aesop was the victim of a judicial murder: When he did not consider the Delphi people worthy of the generous gifts, he had received for them from King Kroisos, they condemned him to death and threw him off a rock.

Indisputably, however, Aesop was the founder of European fable poetry.

Under Ottoman Rule

The Byzantine Thema of Anatoli (‘Orient’, ‘East’) was overrun by the Seljuk Turks in the aftermath of the Battle of Manazkert (Manzikert; 1071). The Turks had taken complete control in the 13th century, but the ancient name of Phrygia remained in use until the last remnant of the Roman Empire was conquered by the Ottoman Empire in 1453.

The Turkoman-Kurdish Germiyan Principality was established in this area in the 13th century. During the Ottoman period, the Kütahya Sancak belonged to the Anatolia Vilayet until 1827, when the Hüdavendigâr Eyalet was formed.

Population

At the turn of the 19th century, there were 3,578 Armenians in the Mutasarrıflığı, predominantly in the city of Kütahya (2,533) and in its vicinity in the two rural centers of Alinca and Arslanik Yayla, furthermore in the Northwestern part of the kaza Kütahya, in Tavşanli (pop. 320) and Virancik (pop. 200). [2]

Two Rare Exceptions

During the First World War, the Armenian population of the Kütahya Mutesarriflik was spared deportations. According to Raymond Kévorkian – based on the writings of the Armenian journalist Sebuh Akuni (Aguni; 1889-1921) – this was mainly due to the positive attitude of the local Turkish population. The mutasarrıf Faik Ali Bey refused to carry out the deportation orders of the Young Turks’ central government. The second major exception is that Faik Ali Bey was not removed from office because of this.

“Yet, while Mehmed Talat threatened the mutesarif and these notables with retaliation, he seems to have exhibited a certain indulgence in this particular case, a sort of exception that proves the rule. Although, initially, fewer than 5,000 people were supposed to benefit from this exception, several thousand deportees from Bandırma, Bursa and Tekirdağ also profited from the benevolent attitude of the mutesarif and the local population, thus escaping the fate that awaited them on the Konya-Bozanti-Aleppo route. It was ultimately the Grand Assembly of Ankara that would liquidate, a few years later, this oasis of life, after extorting a heavy contribution from it ‘for the defense of the fatherland.’

The histories of a few individuals detained in Çangırı who were among the rare prisoners released on the condition that they reside elsewhere than in Istanbul – the architect Simon Melkonian, Sarkis Arents, the pharmacist Hajian, Kasbar Cheraz, Mikayel Shamdanjian, and Father Vartan Karageuzian – illustrate the uniqueness of the case of the sancak of Kütahya. (…)”[3]

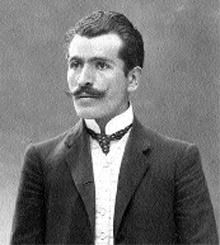

Mutasarrıf Fâik Âli Bey (Ozansoy)

Being of Kurdish origin, Fâik Âli Bey was born on 26 March 1876 in Diyarbakır. His father Said Pasha was not only a provincial governor (Mutasarrıf and Vali), but also a respected poet and historian of his time. The brother of Fâik Âli Bey, Süleyman Nazif, was a courageous journalist and satirist whose works are still respected today. Fâik Âli, who grew up in this environment, like his grandfather Süleyman Nazif Efendi, his father Said Pasha and his brother Süleyman Nazif, is, in addition to his prestigious reputation as a politician, also a respected poet and writer who left behind a remarkable literary work.

After his education at the Military High School in Diyarbakır, Fâik Âli Bey attended the College of Politics (Mülkiye) in Istanbul in 1893. In 1899 he got his first job as a civil servant trainee in Bursa. Afterwards he was appointed to the district administrator (Kaymakam) in the districts Sındırgı, Burhaniye, Pazarköy (today: Orhangazi) and after proclamation of the constitutional monarchy in Mudanya. After refusing the appointment as a district governor in Kırşehir, he was appointed provincial governor and served in Midilli (Lesbos), Beyoğlu, Üsküdar and finally in Kütahya.

At the beginning of 1915, Fâik Âli received a letter from his brother Süleyman Nazif warning him against direct or indirect participation in the upcoming violence, with the postscript that he should not defile the honour of his family. Fâik Âli thereupon gathered the Muslim elite of the city and brought them to a written testimony of the political as well as economic importance of the Armenians for the province and their honesty and loyalty.

When he received the order to deport the Armenian population in his jurisdiction, he publicly announced that he would not obey it. It is known that he did everything in his power to ensure that the Armenians living in Kütahya were not deported. In addition, Armenians who were deported from other places or who were somehow connected with Kütahya were employed in nearby villages to prevent an accumulation of the Armenian population in Kütahya which could cause a stir in the Young Turks’ (Unionist) central government and put the Armenians as a whole in danger. It should be emphasised that Fâik Âli acted with the support of the local Muslim population, with particular mention of two distinguished families: the Kermanyizâdes and Hocazâdes Rasik. (4)

Some members of the Committee for Unity and Progress, who had previously been among the signatories of the above-mentioned testimony, called on Mutasarrıf to carry out the deportation order after all. Fâik Âli Bey then threatened them with bringing them to account for their false statement to the state, clarifying at what point in time they had lied: when they had signed their statement testifying to the loyalty of the Armenians or when they accused them. In any case, they would have lied, in front of the state!

Because of the complaint of the Ittihatists, Fâik Âli Bey came into conflict with Talât Pasha and asked for his dismissal from office, but this was refused. During a short absence of Fâik Âli Bey, the Armenians were forced into forced conversion. This action ended with his return.

Fâik Âli also founded an Armenian school for the deported children. When some Armenian communities sent him money as thanks, he used this money to buy food for the impoverished non-resident Armenians, whose fate he was otherwise officially incapable of rescuing.

Fâik Âli Bey remained in Kütahya until 14 January 1918. He refused a job in Gelibolu and instead returned to Istanbul, where he worked as a teacher. After the passing of the law on names, he took the name “Ozansoy” in 1936 and wrote, as in previous years, in the literary magazines Servet-i Fünun and later the Fecr-i Ati movement. In 1936, he founded a new magazine with his son Munis Faik Ozansoy, who was also a literary figure.

Fâik Âli Bey died on 1 October 1950 and was buried in accordance with his legacy next to the ‘great poet’ (Şair-i Âzam) Abdülhak Hamit Tarhan at the Zincirlikuyu cemetery in İstanbul.

In 1919, he wrote an open letter to the Armenian journalist Sahak from the newspaper Tasvir-i Efkar, which once again makes clear how principled Fâik Âli had proceeded. It is a pity that his extraordinarily sensitive language cannot be fully reflected in the translation:

“… while thanking you, I take the liberty of reminding you of a much more important task than those you consider necessary to exercise: In the times when I had made your protection from being disadvantaged by the terrible events my official and human task was, the entirety of all Muslims in and around Kütahya was in harmony with me, both in thought and action. More than that, not only did they feel the same, but they became the protectors and companions of countless Armenian families who, drifting in the flood of misdeeds, from other cities and provinces, sought care on your soil. Both strangers and locals have seen that your goods, your life and your honour have always remained untouchable. This is exactly what you should never forget!

But no, not forgetting is not enough! At the same time it should be a conscientious task to shout the following with the strongest voice to the civilizations of the world and all mankind: The acts of violence have not been committed with the approval of the population, they are murders of some ungrateful lawless robbers and murderers (original: vatan haramisi). Your Turkish fellow citizens are capable of sublime feelings which do not allow such complicity. Yes, please share with us the certainty that the Armenians are just as disadvantaged as the Turks and the Turks as well as the Armenians – disadvantaged and excusable (original: mağdur ve mazur).

If the guilt and sin of the war and the massacres in the execution of which the masses were involved are not seen as the intention and action of individuals, but are entered in the debt register of humanity, the soul of truth as well as of justice will be trampled underfoot. At the same time, in the event that innocent millions of a population are declared guilty and involved (original: muhatap), even though a part of this atrocity against the Armenians ascribed to the whole is the work of a few or a few hundred, the fulfillment of human and divine justice, which we persistently and eagerly await, will be considerably weakened.

If you consistently proclaim this truth together with us, you will prove once again that it is not you personally who are needy and demanding, but rather you who act as the absolute defender of justice and its primacy (original: perestar), and are thus in the right and deserve it.

I ask for the recognition of my lasting esteem. May your salvation continue (Bâkî hissiyat-ı ihtiramkârânemin kabulüyle muhabbet-i kalbiyenizin devamını rica ederim)!

In friendly esteem, my Lord (Muhibb-i muhterem efendim),

Fâik Âli Ozansoy

Source: http://www.aga-online.org/hero/faik-ali-bey.php?locale=de