Toponym

The principality (beylik) was named after its founder, Menteşe. It was also called Mendessa or Muğla (Mougla), after its administrative seat.

Administration

The sancak of Menteşe (Muğla) comprised the six kazas of Muğla with the administrative seat of same name, Muğla, Milas, Makri (now Fethiye) Bodrum, Köyceğiz and Marmaris.

The present-day Muğla Province of Turkey was named the sub-province (sancak) of Menteshe until the early years of the Republic of Turkey, although the provincial seat had been moved from Milas to Muğla with the establishment of Ottoman rule in the 15th century.

Population

According to the first census data in the Ottoman Empire, the population of the sancak of Menteşe in 1831 was 52,460, of which 49,830 were Muslims and 2,578 were non-Muslims. According to the results of the 1893 Ottoman General Census, in which also women and children were counted, among a total of 146,022 inhabitants 135,207 were Muslims and 10,815 non-Muslims.[1]

In the 1914 census, the total population of the sancak was 188,916 [2], including 19,923 Greek Orthodox Christians. There were relatively insignificant Armenian and Jewish populations. In the census documents dated 1915 and 1921, there was not much change in this population.

Ecclesiastically, the Greek Orthodox population of this sancak belonged to the Diocese of Pisidia (Adalia), composed of fifteen communities with 32,784 inhabitants.[3]

Notable Greeks born in Muğla or deriving from Muğla

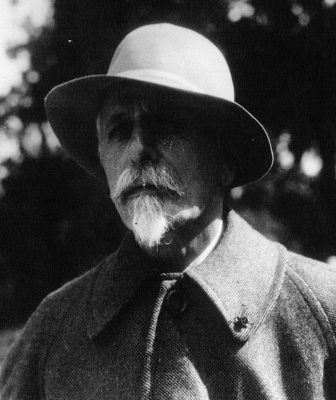

Basil Zaharoff (Βασίλειος Ζαχάρωφ; b. Muğla, 1849 – d. Monte Carlo, 1936), arms dealer & industrialist

Anna Mouglalis (Άννα Μουγλάλη, b. 26 April 1978, Fréjus/France), French actress and model, as attested by her name, can trace her roots to the city of Muğla.

History

Menteşe (Ottoman Turkish: منتشه,) was the first of the Anatolian beyliks, the frontier principalities established by the Oghuz Turks after the decline of the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum. Founded in 1260/1290, it was named for its founder, Mentesh(e) Bey. Its capital city was Milas (Mylasa) in southwestern Anatolia.

The heartland of the beylik corresponded roughly to ancient Caria or to the early modern Muğla Province in Turkey, including the province’s three protruding peninsulas. Among the important centers within the beylik were the cities of Beçin, Milas, Balat, Elmali, Finike (Phoenix), Kaş, Makri (modern Fethiye), Muğla, Çameli, Acıpayam, Tavas, Bozdoğan, and Çine. The city of Aydın (formerly Tralleis, latinized Tralles) was controlled by this beylik for a time, during which it was called ‘Güzelhisar’; it later was transferred to the Aydinids in the north, who renamed the city for the founder of their dynasty.

The Beylik of Mentese were serious regional naval powers of their time. They were sometimes referred to as the Sea Turks as they were the first seafaring Beylik. The Beylik produced fine boats using special trees harvested from the expansive forests in the high coastal mountains. These boats sailed well and were well built and the models for today’s Gulet Sailboats, which are prevalent in the Aegean Sea in both Greece and Turkey. The Beylik even conquered Rhodes and many other islands, which are still referred to as the “Mentese” Islands or The Dodecanese. During the Siege of Constantinople in 1453, approximately 40% of the Ottoman Navy was from the Mentese Beylik.

Architecturally, the Mentese Beylik had a significant impact on later Ottoman Architecture. They were the first Beylik to construct large precision cut stone buildings and became experts in building domes and archways. The region itself was an important source of marble and stone since the Roman times and continues to be Turkey’s top stone export region.

Menteşe Bey first submitted to Ottoman rule in 1390, during the reign of Bayezid I, “the Thunderbolt”. After 1402, Tamerlane restored the beylik to Menteşoğlu İlyas Bey, who recognized Ottoman overlordship in 1414. A dozen years later, in 1426, Mentese was incorporated into the Ottoman realm.

Destruction

Before and during the First World War (1913-1918)

The Diocese of Pisidia (Adalia)

“Already during the Balkan War this Diocese (…) was terrorised by a band of Moslem Cretans, who gave themselves up to all sorts of persecution and oppressions of every description including murders and massacres. Two brothers, Panayiotis and Savas, natives of Alaya, who were working in the farm of Hadji loannou Papazoglou, close to Adalia, were, among others, their victims (9th January, 1913). The Moslem Cretans also took an active part in the boycott against the Greek element.

The economic warfare directed against Adalia, Bourdour [Burdur], Sparta and Phiniki [Finiki; Phoenix], began with the arrival at Adalia of a general inspector of the C.U.P. The supervision of the movement was entrusted to the Cretans, who went all over the country, whip in hand, forcing the Moslems, under oath, and under the very eyes of the authorities, to give up every intercourse with the Christians, and not to pay their debts to them.

This situation had of course its consequences. Rumors were cleverly spread to the effect that the persecutions of the same nature as those of Thrace and Asia-Minor were imminent, with the result that trade came to a complete standstill, whilst finance was in a very bad condition. Further the inhabitants were ordered by the Moslem Muhtars to quit within twenty-four hours, so that the Christians were obliged to resort to Adaha and Bourdour abandoning all they owned to the discretion of the Turks.

In spite of the general inspector issuing orders, prohibiting crime against the Christians towards the end of June, 1914, the merchant Athanassoglou, a native of Sparta, was murdered in the village of Youva [Yuva]. A bag stained with blood, containing his books, was found in a well. Athanasse Philipidis, established fifteen years in the village of Kemer, was murdered by Turkish peasants. Jeremiah Danopoulos, established at Horzoum of Gueul-Hissar, was beaten mercilessly and put to death with an axe. The sexual organs of Kyriakos Hadji Aslanoglou, and Cosmas Damaroglou were cut off. They both died. George Demirayakoglou, of Kapakli, was assassinated. The families of George and Constantine Sazakoglou were murdered under most tragic circumstances.

Regarding the Community of Bou[r]dour, a general massacre was to have taken place on the 21st September, 1914 ; but an earthquake so disastrous to the community seems to have had the result of determining the Turks to put off their scheme to some more favorable moment. The Community, however, underwent many trials owing to requisitions, all kinds of extortions, the exile of 200 of its notables into the interior, and the barbarous conduct in general of the Turkish immigrants towards the Christians.

Besides the Greeks of the aforementioned localities, who took refuge in Aidir and Bou[r]dour, many inhabitants of Myron were obliged owing to the situation to emigrate with their families to Castelorizo in June, 1914. Antiphelles was evacuated the same month, and the inhabitants of Phiniki were dispersed. The Christian element in general of this corner of Asia Minor, under the influence of the events in the District of Smyrna in 1914, now began to expatriate.

The European war offered the Young Turks an occasion to finish up their work of destruction. The few remaining inhabitants of the village of Phinica [Finiki, Phoenix], with a few exceptions, expatriated. Those of Macri [Makri] and Bevisa, and the small agglomerations of Kiuldjek [Köyceğiz?] and Peldjigez were expelled at different intervals (from September, 1916, to August, 1918) to the interior, without any mercy to the infirm, women and children, or even the sick.

N.B. The inhabitants of the islet of Tarsana, 376 in number, expatriated owing to the attack of the Turkish troops, and left their fortunes worth £162,000 behind them.”[4]

“Undoubtedly murders form a part of the plan of persecution of the Greek populations. This is evident from the report of the Consulate General of Smyrna, No. 60, dated December 22, 1915 (Ministerial Archives, No. 5960), according to which, in the District [sancak] of Mendessa [Menteşe] alone, exclusive of the Sanjak of Mougla, over 200 Greeks were murdered from July, 1914, to the end of December, 1915.”[5]

Even towards the end of the First World War, Ottoman Greeks were deported in Western Anatolia. A documentation of the Ecumenical Patriarchate mentions the inhabitants of four parishes of the Diocese of Helioupolis who were deported to the sancak Mentese, while this sancak’s Greek Orthodox population was expelled and deported:

“Finally in July, 1918, feigning to enforce the law upon defaulters, the order was given that the remaining Greek inhabitants of these communities as well as those of: 13. KOKINOHORI, 14. MASSAT, 15. YENI-PAZAR, and 16. KARADJA-SOU [Karacasu], should be expelled and deported. Some few were sent to Mougla [Muğla], and the others exiled to some Turkish villages. The evacuated communities were completely destroyed, many of whose inhabitants died of fatigue, hunger, privations, illness, etc.”[6]

1919

„In a report from Adalia, dated August 16, 1919 the following statement was included: ‘Besides the three Greeks who some time ago disappeared between Adalia and Stanaz, eight other Greeks were lost: three at the mill of Doryan three weeks ago, and five or six days ago seven more men, an Armenian and six Greeks, disappeared at Kumnitza (near Phoenix [Grk.: Finiki]). Brigands attacked that village in broad daylight and after much looting of goods and money, they carried off those seven Christians to some unknown direction. No Christians are left in the surrounding villages. None of our people dare to go to the Turkish villages to work, and the farmers have abandoned their fields to their fate. Some days ago, Turkish gendarmes have murdered on the quay of Macri [Makri; today Fethiye] the physician of the Greek Cross in that town.’”[7]